* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Kandel and Schwartz, 4th Edition Principles of Neural Science Chap

Lateralization of brain function wikipedia , lookup

Dual consciousness wikipedia , lookup

Neurolinguistics wikipedia , lookup

Affective neuroscience wikipedia , lookup

Limbic system wikipedia , lookup

Eyeblink conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Stimulus (physiology) wikipedia , lookup

Central pattern generator wikipedia , lookup

Sensory substitution wikipedia , lookup

Activity-dependent plasticity wikipedia , lookup

Haemodynamic response wikipedia , lookup

Cortical cooling wikipedia , lookup

Executive functions wikipedia , lookup

Optogenetics wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychology wikipedia , lookup

Brain Rules wikipedia , lookup

Emotional lateralization wikipedia , lookup

Neurophilosophy wikipedia , lookup

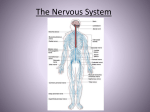

Development of the nervous system wikipedia , lookup

Clinical neurochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Environmental enrichment wikipedia , lookup

Nervous system network models wikipedia , lookup

Embodied language processing wikipedia , lookup

Cognitive neuroscience wikipedia , lookup

Time perception wikipedia , lookup

Neuroesthetics wikipedia , lookup

History of neuroimaging wikipedia , lookup

Embodied cognitive science wikipedia , lookup

Evoked potential wikipedia , lookup

Metastability in the brain wikipedia , lookup

Premovement neuronal activity wikipedia , lookup

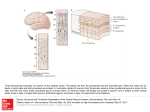

Anatomy of the cerebellum wikipedia , lookup

Holonomic brain theory wikipedia , lookup

Synaptic gating wikipedia , lookup

Human brain wikipedia , lookup

Cognitive neuroscience of music wikipedia , lookup

Aging brain wikipedia , lookup

Neuroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

Neuroplasticity wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Motor cortex wikipedia , lookup

Neuroanatomy wikipedia , lookup

Neural correlates of consciousness wikipedia , lookup

Inferior temporal gyrus wikipedia , lookup