* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Limbic systems for emotion and for memory, but no

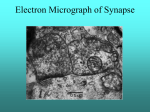

Activity-dependent plasticity wikipedia , lookup

Stimulus (physiology) wikipedia , lookup

Neurophilosophy wikipedia , lookup

Neural coding wikipedia , lookup

Development of the nervous system wikipedia , lookup

Apical dendrite wikipedia , lookup

Brain Rules wikipedia , lookup

Emotion perception wikipedia , lookup

Neuroanatomy wikipedia , lookup

Clinical neurochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Biology of depression wikipedia , lookup

Holonomic brain theory wikipedia , lookup

Cognitive neuroscience wikipedia , lookup

Nervous system network models wikipedia , lookup

Executive functions wikipedia , lookup

Metastability in the brain wikipedia , lookup

Optogenetics wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Premovement neuronal activity wikipedia , lookup

Neuroplasticity wikipedia , lookup

Human brain wikipedia , lookup

Anatomy of the cerebellum wikipedia , lookup

Environmental enrichment wikipedia , lookup

Cortical cooling wikipedia , lookup

Time perception wikipedia , lookup

Cognitive neuroscience of music wikipedia , lookup

Aging brain wikipedia , lookup

Neuroesthetics wikipedia , lookup

Eyeblink conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Emotional lateralization wikipedia , lookup

Neuroanatomy of memory wikipedia , lookup

Affective neuroscience wikipedia , lookup

Neural correlates of consciousness wikipedia , lookup

Limbic system wikipedia , lookup

Synaptic gating wikipedia , lookup

Motor cortex wikipedia , lookup

Prefrontal cortex wikipedia , lookup

Neuroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

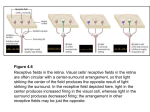

Feature detection (nervous system) wikipedia , lookup

Orbitofrontal cortex wikipedia , lookup