* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The genomic landscape of meiotic crossovers and gene

Copy-number variation wikipedia , lookup

DNA supercoil wikipedia , lookup

Molecular cloning wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative trait locus wikipedia , lookup

Gene desert wikipedia , lookup

Cancer epigenetics wikipedia , lookup

Genome (book) wikipedia , lookup

Minimal genome wikipedia , lookup

Dominance (genetics) wikipedia , lookup

Oncogenomics wikipedia , lookup

X-inactivation wikipedia , lookup

Holliday junction wikipedia , lookup

Neocentromere wikipedia , lookup

Vectors in gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Zinc finger nuclease wikipedia , lookup

Cell-free fetal DNA wikipedia , lookup

Genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Deoxyribozyme wikipedia , lookup

Extrachromosomal DNA wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression programming wikipedia , lookup

Genomic imprinting wikipedia , lookup

Genealogical DNA test wikipedia , lookup

Whole genome sequencing wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Nutriepigenomics wikipedia , lookup

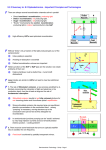

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

Designer baby wikipedia , lookup

Human genome wikipedia , lookup

Epigenomics wikipedia , lookup

Human Genome Project wikipedia , lookup

Pathogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Bisulfite sequencing wikipedia , lookup

History of genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Non-coding DNA wikipedia , lookup

Therapeutic gene modulation wikipedia , lookup

Microsatellite wikipedia , lookup

Metagenomics wikipedia , lookup

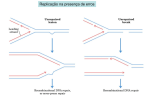

Homologous recombination wikipedia , lookup

Genomic library wikipedia , lookup

No-SCAR (Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering) Genome Editing wikipedia , lookup

Artificial gene synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Genome evolution wikipedia , lookup

Microevolution wikipedia , lookup

Genome editing wikipedia , lookup

Site-specific recombinase technology wikipedia , lookup