* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download reviews

Copy-number variation wikipedia , lookup

Segmental Duplication on the Human Y Chromosome wikipedia , lookup

Gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Gene therapy of the human retina wikipedia , lookup

Human genome wikipedia , lookup

Population genetics wikipedia , lookup

Non-coding DNA wikipedia , lookup

Vectors in gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Epigenetics of diabetes Type 2 wikipedia , lookup

Transposable element wikipedia , lookup

Gene nomenclature wikipedia , lookup

Essential gene wikipedia , lookup

Long non-coding RNA wikipedia , lookup

Epigenetics of neurodegenerative diseases wikipedia , lookup

Oncogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Polycomb Group Proteins and Cancer wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative trait locus wikipedia , lookup

Pathogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Therapeutic gene modulation wikipedia , lookup

Gene desert wikipedia , lookup

Nutriepigenomics wikipedia , lookup

Helitron (biology) wikipedia , lookup

History of genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Genomic imprinting wikipedia , lookup

Biology and consumer behaviour wikipedia , lookup

Minimal genome wikipedia , lookup

Ridge (biology) wikipedia , lookup

Site-specific recombinase technology wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression programming wikipedia , lookup

Genome (book) wikipedia , lookup

Artificial gene synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Epigenetics of human development wikipedia , lookup

Designer baby wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression profiling wikipedia , lookup

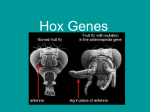

REVIEWS SPLITTING PAIRS: THE DIVERGING FATES OF DUPLICATED GENES Victoria E. Prince* and F. Bryan Pickett ‡ Many genes are members of large families that have arisen during evolution through gene duplication events. Our increasing understanding of gene organization at the scale of whole genomes is revealing further evidence for the extensive retention of genes that arise during duplication events of various types. Duplication is thought to be an important means of providing a substrate on which evolution can work. An understanding of gene duplication and its resolution is crucial for revealing mechanisms of genetic redundancy. Here, we consider both the theoretical framework and the experimental evidence to explain the preservation of duplicated genes. POLYPLOIDY A polyploid organism has more than two sets of chromosomes (two sets being the prevalent diploid state). For example, a tetraploid organism has four sets of chromosomes and an octaploid has eight sets. ALLOTETRAPLOIDY The generation of the tetraploid state by fusion of two nuclei from different species. For example, two fertilized diploid oocytes can fuse such that the newly formed single egg has two complete sets of chromosomes. *Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, The University of Chicago, 1027 East 57th Street, Chicago, Illinois 60615, USA. ‡ Department of Biology, Loyola University of Chicago, 6525 North Sheridan Road, Chicago, Illinois 60626, USA. Correspondence to V.E.P. e-mail: [email protected] doi:10.1038/nrg928 At the dawn of the new genomic era, we already know the entire genome sequences of several organisms, and the mysteries of genome structure, organization and evolution are at last beginning to be unveiled. Recent studies have shown that a surprisingly large number of duplicated genes are present in all sequenced genomes, revealing that there is frequent evolutionary conservation of genes that arise through local, regional or global DNA duplication events1. Tandem, regional or whole-genome duplication events produce pairs of initially similar genes, which can ultimately become scattered throughout a dynamically rearranging genome2. Complete or partial POLYPLOIDY is found in many plants. It is also found in specific vertebrates, such as salmonid fishes and certain frogs, including the popular embryology model Xenopus laevis3. Polyploidy can occur as the result of whole-genome duplication, through ALLOTETRAPLOIDY or AUTOTETRAPLOIDY. All vertebrate animals, despite their generally diploid state, carry large numbers of duplicated genes. This has been interpreted by some as evidence that two rounds of whole-genome duplication occurred at the origin of the vertebrate lineage, ~400 million years ago (Mya; the ‘2R’ hypothesis4–6; see phylogenetic tree and green text in FIG. 1). Whether or not this event occurred, there have certainly been duplication events on a broad scale during vertebrate evolution, although these might represent ‘segmental’ duplications of large stretches of DNA or perhaps of whole chromosomes. The occurrence of a whole-genome duplication event in the main branch of the vertebrate lineage that produced all the TELEOST fishes, at least 110 Mya, is more widely accepted7 (FIG. 1). As more whole-genome sequences become available, it is becoming increasingly important to understand the forces that have shaped their organization. Here, we review the mechanisms that lead to retention versus loss of duplicated genes and consider the broader implications at both a genetic and an evolutionary level. In particular, we use examples from vertebrates and plants to focus on sub-functionalization, by which duplicate genes each lose a different subcomponent of their function, therefore reducing their joint activity to that of the single ancestral gene. This mechanism provides an appealing model to explain why so many genes have been retained after duplication. Evolutionary fates of duplicated genes No matter how duplicate genes arise, if they are duplicated in their entirety (including regulatory elements) then they can show inter-gene REDUNDANCY8–10. Classical models predict two potential fates for these duplicate gene pairs11,12. The most likely fate is that one of the pair will degenerate to a pseudogene or be lost from the genome due to the vagaries of chromosomal remodelling, locus deletion or point mutation (in a process known as NON-FUNCTIONALIZATION). Gene loss through these processes is permissible because only one of the duplicates is required to maintain the function provided NATURE REVIEWS | GENETICS VOLUME 3 | NOVEMBER 2002 | 8 2 7 © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS d nn ne ed fin Cichlids, striped bass Medaka Mammals fis y- he s Ra Pufferfish be s 110 Mya Lo he Zebrafish Avians -fi fis Teleost fishes >4 Hox clusters Tetrapods 4 Hox clusters Amphibians Lungfish Genome duplication Bowfin Sturgeon Bichir Duplications/ 2R Coelacanths >400 Mya Sharks and rays Lamprey Amphioxus One Hox cluster Figure 1 | Phylogeny of chordates. The tree indicates the approximate timing of whole-genome (green) and Hox gene (red) duplication events. ‘2R’ refers to the two rounds of whole-genome duplication that are believed by some to have occurred at the origin of the vertebrate lineage. Mya, million years ago. Modified with permission from REF. 91 © (2002) Elsevier Science. AUTOTETRAPLOIDY In contrast to allotetraploidy, both sets of chromosomes are derived from the same species. This can occur in the fertilized oocyte if the nucleus divides but the cell does not. TELEOST A bony fish that belongs to the infraclass Teleostei (comprising more than 20,000 species), which includes nearly all the important food and game fish, and many aquarium fish. REDUNDANCY When two genes can fulfil an equivalent function. Because of pleiotropy, redundancy is often partial, with two genes having overlapping rather than equivalent functions. NON-FUNCTIONALIZATION When one of two duplicate genes acquires a mutation in coding or regulatory sequences that ultimately renders the gene non-functional. PURIFYING SELECTION Selection against deleterious alleles, which will be eliminated from the population. NEO-FUNCTIONALIZATION When one of two duplicate genes acquires a mutation in coding or regulatory sequences that allows the gene to take on a new and useful function. CONSERVED SYNTENY (syn, same; teny, thread). Homology of gene order between two chromosomes or chromosomal segments, within or between species. 828 by the single, ancestral gene, leaving one gene under PURIFYING SELECTION and the other gene free to accumulate evolutionarily neutral or nearly neutral loss-of-function mutations in the coding region. A less frequently expected outcome is that a population acquires a new, advantageous allele as the result of alterations in coding or regulatory sequences, exposing the formerly redundant gene to new and distinct selective constraints. Mutations that lead to such novel gene functions (a process called NEO-FUNCTIONALIZATION) are assumed to be extremely rare, so the classical model predicts that few duplicates should be retained in the genome over the long term. The classical model, however, fails to explain the existence of the many duplicated genes found in extant genomes. Nadeau and Sankoff estimated that around half of all duplicated vertebrate genes have been maintained13. Recent analyses of the human genome have revealed that at least 15% of human genes are indeed duplicates14, with segmental duplications covering 5.2% of the genome15. Similarly, comparative genomics has shown that the zebrafish genome retains at least 20% of the gene pairs that arose from the latest duplication event in this lineage, which occurred at least 110 Mya (REF. 7). The retention of ancient duplicates is also common in plants: in Arabidopsis, 17% of genes are found in tandem arrays that contain up to 23 genes, and ~31% are members of duplicate pairs that reside in regions of the genome with CONSERVED SYNTENY16. These sequence analyses complement the results of experiments that have assessed gene function using genetic, molecular and developmental approaches; such studies indicate that duplication often results in continuing partial genetic redundancy. Expression analyses indicate that extant gene pairs might have, in many cases, partitioned the multiple, often PLEIOTROPIC, functions of single ancestral genes between the descendant duplicates. Population-level models and experimental evidence indicate that gene multifunctionality (BOX 1) might act to potentiate the preservation of duplicated genes. The DDC model. What alternatives exist to non-functionalization and neo-functionalization? A broadly applicable SUB-FUNCTIONALIZATION model was recently proposed by Force and colleagues to explain the prevalence of duplicate genes that are retained in the genome17,18. Sub-functionalization proposes that, after duplication, the two gene copies acquire complementary loss-of-function mutations in independent subfunctions, such that both genes are required to produce the full complement of functions of the single ancestral gene. This general process has been described in detail in the duplication–degeneration–complementation (DDC) model17,18 (BOX 2). For the sub-functionalization Box 1 | The multifunctional nature of genes The recent results derived from evolutionary, developmental and genomic studies in various organisms highlight the key roles of gene and phenotypic multifunctionality during organismal evolution20,85. Genetic evidence of gene multifunctionality has a long history and was first described in maize86 and Drosophila 87, in which non-quantitative ALLELIC SERIES were found. Some members of these allelic series could not be placed on a simple continuum, in which alleles retained a proportion of the activity of wild-type alleles. Different alleles had an impact on different qualitative patterns of characters, contributing to unique phenotypes. Such observations supported Hermann Joseph Muller’s famous proposal that a large array of non-null alleles exists for many genes, which led eventually to a scheme of classifying allele function that was based on his reinterpretation of Gregory Bateson’s allelomorphy (which was Bateson’s hypothesis that allelomorphs (or alleles) encode ‘unit characters’ that contribute to an observed Mendelian character). In addition, the existence of unique alleles that cause unpredictable phenotypes also led Muller to promote the ‘sub-gene hypothesis’ of Serebrovsky and Dubinin88. This hypothesis posited the first strongly articulated model that individual genes have not one, but a set of functions, each contributed by independently mutable regions of chromatin at a single locus. Muller and colleagues made various attempts to ‘divide’ sub-gene functions using chromosomal rearrangements and, although their work was inconclusive, the apparent interaction of position effect and the location of inversion breakpoints on the phenotypic severity of rearranged alleles indicated that some subdivision of gene functions was possible89. Muller also identified Drosophila dumpy alleles that affect only wing or only thoracic characters87, and the Small eye (Sy) mutation discovered by Bridges turned out to be an allele of the mutation outstretched wings (od; now known as os) observed by Muller90. These observations confirmed a key tenet of the ‘sub-gene hypothesis’: functions of a gene can be independently identified and separated by mutation. The insights gained through observations made by Muller, Emerson and other prominent early twentieth century maize and Drosophila geneticists are the foundation of our current appreciation of the multifunctional nature of individual genes. | NOVEMBER 2002 | VOLUME 3 www.nature.com/reviews/genetics © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS Box 2 | The duplication–degeneration–complementation model The duplication–degeneration–complementation (DDC) model relies on complementary degenerative changes in a pair of duplicate genes, such that the Duplication duplicates together retain the original functions of their single ancestor. The red, blue and green boxes denote cis-regulatory elements, although degenerative mutations in any functionally discrete, independently mutable portion of a locus (a protein domain or alternative splice site, for example) could participate Degeneration in sub-functionalization. The mathematical models that underlie the DDC concept depend ultimately on population-level processes, including mutation rates and the changes in allele frequency that occur owing to GENETIC DRIFT. Complementation Initially, a contest occurs between mutations that affect any one sub-function of a gene and null mutations that destroy the ability of a gene to produce a functional protein. A mutational event that affects a sub-function of either duplicate allows both genes to persist in individuals in a population, therefore potentially allowing both genes to experience subsequent mutations. Alternatively, any mutational event that negatively affects a coding region can instantly convert the affected duplicate into a pseudogene, preventing subsequent participation in sub-functionalization. Until sub-functionalization has occurred, duplicates can experience sub-function or null mutations in the coding region. The DDC model depends on parcelling out the pre-existing sub-functions of ancestral genes, potentially leading to a reduction in the pleiotropy level per gene. As a consequence, the sub-functionalized duplicates are less constrained by selection than the single ancestral gene, which had to maintain the capacity to fulfil all functions. Selection can therefore act independently on each duplicate, increasing its functional specificity. PLEIOTROPY When a single gene has a role in several processes. SUB-FUNCTION Any functionally discrete, independently mutable portion of a locus. For example, a cis-regulatory element, a protein domain or an alternative splice site. ALLELIC SERIES A series of alleles that can be present at the same locus and that produce graded phenotypes. GENETIC DRIFT The increase or decrease in allele frequencies in populations due to chance. LENS CRYSTALLIN A protein that accumulates at high concentration in the eye and that forms the crystallin lens. DEGENERATIVE MUTATION A sequence change that causes a loss of function of the affected sub-function or gene. INDIVIDUAL RELATIVE FITNESS The capacity of the individual to survive and reproduce. EFFECTIVE POPULATION SIZE The equivalent number of breeding adults in a population after adjusting for complicating factors, such as non-random variation in family size or stochastic fluctuation in population size. model to work, sub-functions need to be independent, such that mutations in one will not affect another. In many cases, eukaryotic enhancers can act as sub-functions or components of sub-functions due to their modular structure. Furthermore, transcription-factorbinding sites are short (often just 8–12 bp), indicating that point mutations might lead frequently to the disruption or creation of sites19. These properties of regulatory sequences have led many researchers to emphasize that evolutionarily important changes might happen primarily at the level of gene regulation rather than protein function20,21. So, a likely way for sub-functionalization to occur is through complementary changes in regulatory elements, perhaps leading to two separate expression domains that together recapitulate the more complex single expression pattern of the ancestral gene17,22. Aspects of this idea were previously proposed by several groups. The first paper to put forward clearly the general idea of sub-functionalization came from Piatigorsky and Wistow 23, who proposed a ‘gene sharing’ model. Their work with LENS CRYSTALLINS led them to suggest that the acquisition of two expression domains could precede a duplication event, with each duplicate later losing one of the two expression domains. Similar ideas were expounded by Hughes24, who suggested that DEGENERATIVE MUTATIONS could lead to the preservation of duplicated genes. Along similar lines, Averof and colleagues suggested that tandem duplications might often produce duplicates with differential partitioning of regulatory elements, such that both genes are required to recapitulate the single ancestral expression pattern25. The probability of sub-functionalization aiding the preservation of duplicate gene loci was also explored independently as part of Stoltzfus’ general model of the contribution of neutral mutations to the diversification of gene function26. Whether two duplicated genes are initially preserved through sub-functionalization or neo-functionalization, they are likely to retain lingering redundant sub-functions. This redundancy can be resolved ultimately through subsequent rounds of degenerative, complementary mutations in remaining sub-functions. So, DDC processes can occur subsequent to a neo-functionalization event. The DDC process also requires that subfunction mutant alleles rise to high frequencies in populations, supplanting the ancestral alleles that were generated at the moment of duplication. Sub-function mutations would have a low impact on INDIVIDUAL RELATIVE FITNESS and would, in effect, be neutral or nearly neutral to selection. Under such near-neutrality, genetic drift has a major impact on the overall likelihood that sub-functionalized alleles will become fixed in a population. In common with other drift-based models, the probability of sub-functionalization after whole-genome duplication is extremely sensitive to the EFFECTIVE POPULATION SIZE and the null mutation rate for individual genes18. Mathematical modelling and computer simulations18,27 predict that populations experiencing high mutation rates (10−4 per site per generation) are only likely to NATURE REVIEWS | GENETICS VOLUME 3 | NOVEMBER 2002 | 8 2 9 © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS Box 3 | Hox cluster evolution through gene duplication The Hox genes provide a remarkably conserved system for providing regional identity to the primary body axis of developing embryos. Mutations in Hox genes can lead to marked ‘homeotic’ phenotypes, in which one segment takes on the identity of another. The Hox genes encode transcription factors with a conserved 60 amino-acid DNA-binding homeodomain and are characterized further by their clustered organization on the chromosome. Wherever Hox genes have been looked for among multicellular animals, they have been found — the sole exception, so far, being the basal sponges. The evolution of the Hox clusters is characterized by duplication events. Invertebrates have a single cluster of Hox genes with a variable gene number (Drosophila has 8 genes, amphioxus has 14; see panel a). Comparative analysis has indicated that the common bilaterally symmetric ancestor of amphioxus and Drosophila already had seven Hox genes31. This initial cluster was the result of tandem duplication from a single ancestral Hox gene. Further tandem duplications led to the differing complements of Hox genes in the single clusters of the different invertebrates (for example, all the amphioxus genes indicated in green are believed to have arisen through tandem duplications from an ancestral gene that is related to Drosophila Abdominal-B (Abd-B)). Vertebrates have several Hox clusters as the result of whole-cluster duplications. Tetrapods, including mouse and human, have four Hox clusters on four separate chromosomes, which were generated by at least two large-scale duplication events (panel b; see also FIG. 1). These duplications might have been segmental, including perhaps only the Hox clusters or the entire chromosome on which they lie, or might have been genome-wide. Another duplication event in the lineage that leads to teleosts has led to the presence of more than four Hox clusters in this group, with zebrafish having seven clusters in total (panel c; see also FIG. 1). The organization of the zebrafish clusters32 reveals that many duplicate genes (with respect to a presumed ancestral four-cluster organization) have been lost. So, zebrafish has far fewer than twice as many Hox genes as mouse. In some cases, pseudogenes can be recognized (open circles), revealing the ‘ghost’ of a duplicate gene. Nevertheless, at least 11 duplicated pairs of genes (PARALOGUES) have been retained in zebrafish, possibly as a consequence of sub-functionalization. Modified with permission from REF. 91 © (2002) Elsevier Science. a Drosophila Hypothetical ancestor Amphioxus 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 10 11 12 13 10 11 12 13 2× Duplication b Mouse A B C D 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Duplication c Zebrafish Aa Ab Ba Bb Ca Cb D Paralogue group 830 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 14 preserve duplicates through sub-functionalization if effective population sizes remain below 10,000. By contrast, populations with lower mutation rates (10−6) will have duplicates with a high probability of preservation through sub-functionalization even in populations that exceed 1,000,000 individuals. In larger populations, duplicates are most likely to be preserved by neofunctionalization (as this phenomenon depends on the occurrence of rare beneficial mutations), although DDC processes could act subsequently to resolve remaining redundancy. Genome projects are revealing a history of global and large regional duplication; furthermore, the rate at which single duplicate genes are generated might approach that of the single-nucleotide mutation rate1, indicating that single-gene duplication events might occur at a surprisingly high rate in extant species. Below, we consider some examples in which DDC processes seem to have contributed to retaining duplicate genes, and the implications of this for gene functions and networks. Although our examples are taken from vertebrates and plants, duplication and subfunctionalization are concepts that apply broadly to other organisms. For example, genome-sequencing projects have revealed that supposedly more simple organisms, such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, also have many duplicated genes in their genomes1,28,29. So, the exploration of the functional complementation between gene pairs in model systems should provide us with general information about the fates of duplicated genes. Degenerative complementation in vertebrates The vertebrate Hox genes are a clear example of evolution by gene duplication (BOX 3), providing a nice opportunity to explore some aspects of the DDC model. The Hox genes are also particularly interesting because of their well-known conserved role in the regionalization of the body plan, which has led to extensive analyses of Hox gene function and regulation in the mouse30. All invertebrates seem to have just a single cluster of Hox genes, whereas tetrapod vertebrates, such as mouse and chick, have four clusters (HoxA–D), which are arranged on four separate chromosomes31,32 (BOX 3). More recently, it has been shown that teleost vertebrates have more than four clusters of Hox genes, very probably due to a whole-genome duplication event in their lineage7,33. As both mouse and zebrafish have tractable genetic systems, their Hox genes provide ideal models for investigating the potential functional complementation between duplicate genes. Furthermore, the remarkable conservation of Hox function during evolution allows meaningful comparisons to be made between mouse and zebrafish Hox genes, despite their divergence over ~400 Mya (FIG. 1). The vertebrate Hox genes fall into 13 paralogue groups, with each cluster having fewer than 13 genes (BOX 3). This is presumably a result of the loss of redundant duplicates, as predicted by classical models. Often, more than one member of a vertebrate Hox paralogue group is expressed in a given location, and these paralogous genes tend to have partially redundant functions. | NOVEMBER 2002 | VOLUME 3 www.nature.com/reviews/genetics © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS a 10 hpf 10.5 hpf 12 hpf 16 hpf hoxb1b hoxb1a b Ancestral state Intermediate state Present-day zebrafish hoxb1b hoxb1b hoxb1a hoxb1a Hoxb1 Sub-functionalization Autoregulatory sequences RARE Figure 2 | Zebrafish duplicate genes subdivide ancestral mouse Hoxb1 expression. a | Expression patterns of zebrafish hoxb1 duplicate genes in embryos. Embryos are shown in dorsal view with the anterior to the top. Double in situ hydridizations reveal the expression of hoxb1 genes (purple) and krox20 (now known as egr2; red), which is a marker for rhombomere (r)3 and r5. The hoxb1b gene is expressed transiently in r4, up to the 10 hours post fertilization (hpf ) stage, then gradually retreats towards the posterior. By contrast, hoxb1a has a later onset of expression (10 hpf) and maintains a stable expression domain in r4 due to autoregulatory control. Together, these expression patterns recapitulate the expression of the ancestral mouse Hoxb1 gene. b | The diagram shows steps by which the expression of the ancestral mouse Hoxb1 gene might have been partitioned into those of zebrafish hoxb1a and hoxb1b. The early expression of mouse Hoxb1 depends on a 3′ retinoic-acid response element (3′ RARE)92, while the r4 stripe is maintained through an autoregulatory mechanism by three Hox/cofactor binding sites93. Zebrafish hoxb1b has a 3′ RARE similar to that of mouse Hoxb1, but has point changes in each of the Hox/cofactor autoregulatory sites, consistent with the absence of a late r4 expression domain for this gene. By contrast, zebrafish hoxb1a retains perfect copies of all three Hox/cofactor autoregulatory sites, but has no 3′ RARE element, which is consistent with the lack of early expression. Together, the zebrafish hoxb1a and hoxb1b genes therefore recapitulate the expression of the ancestral mouse Hoxb1 gene. PARALOGUES Homologous genes that are related by a duplication event. For example, mouse Hoxa2 and Hoxb2 are paralogues. NEURAL CREST A vertebrate-specific migratory cell type that derives from the dorsal-most aspect of the neural tube and contributes to many tissues, including the peripheral nervous system and cranium. One interesting example of this is the mouse Hox paralogue group 3 genes. Although null mutants for Hoxa3 and Hoxd3 have independent phenotypes that affect 34,35 NEURAL-CREST-derived structures and vertebrae36, respectively, double mutant phenotypes lead to a complete absence of specific vertebral elements, revealing redundancy between the genes37. The non-redundant functions of the two paralogues must be a consequence of differences in their cis-regulatory control rather than their coding sequences, as Hoxa3 and Hoxd3 proteins are functionally interchangeable38. Surprisingly, the overall expression patterns of the two genes seem superficially similar; however, the data reveal that the details of their cis-regulation, probably including variations in level of expression, have profound functional consequences, such that each gene has an important patterning role in a separate tissue. These two paralogue group 3 genes probably represent an example of functional complementation, although we need a more detailed understanding of differences in the regulation of the two genes, as well as a reconstruction of the ancestral condition based on comparative data, to investigate this further. Among the zebrafish Hox genes, there are at least 11 instances in which duplicate genes have been retained (BOX 3). In the case of the hoxb5a duplicates, expression analysis coupled with gain-of-function studies indicates that both genes have been retained possibly as a result of sub-functionalization39. Recent studies in V.E.P.’s laboratory40,41 have focused on zebrafish Hox genes in paralogue group 1, which includes a pair of genes — hoxb1a and hoxb1b — that are duplicated with respect to the ancestral four-cluster state. In this study, we have made use of the strengths of the zebrafish system, which include both the ability to test gene function directly and the recent availability of genomic sequence data from the Sanger Sequencing Centre. The results of comparing the expression patterns, functions and regulatory elements of the zebrafish hoxb1 duplicates with those of the mouse Hox paralogue group 1 genes indicate that both zebrafish gene copies were preserved as a consequence of complementary degenerative mutations, as described below40. In accordance with the DDC model, the zebrafish hoxb1 duplicates seem to have subdivided the ancestral mouse Hoxb1 expression pattern. So, zebrafish hoxb1b shares the early expression pattern of mouse Hoxb1, in the hindbrain of gastrulating embryos, whereas hoxb1a shares the later expression of mouse Hoxb1, in a single segment of the neurulation-stage hindbrain (RHOMBOMERE (r)4; FIG. 2a). The DDC model further predicts degeneration of discrete and complementary cis-regulatory elements in the two zebrafish duplicates, and such changes in these regulatory elements can indeed be recognized40 (FIG. 2b). The degenerative loss of regulatory modules in each of the two duplicates is likely to have been sufficient to allow the preservation of the two genes, in accordance with the DDC model. As the analysis of the expression patterns and regulatory elements of zebrafish hoxb1a and hoxb1b has shown that these duplicates experienced complementary, degenerative mutations during their evolution40, the two genes might be expected to subdivide the function of the single Hoxb1 ancestral gene. Although we cannot know this function, it is probably similar to the function of mouse Hoxb1. The primary phenotype of null mutants of mouse Hoxb1 is a change in neuronal identity: rhombomere-4-derived facial neurons do not undergo their characteristic posterior migration42–44. Knockdown of the zebrafish hoxb1 duplicates using antisense MORPHOLINOS has shown that hoxb1a is similarly required for facial neuron migration40. However, the hoxb1b gene does not have a role in this process and NATURE REVIEWS | GENETICS VOLUME 3 | NOVEMBER 2002 | 8 3 1 © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS Ancestral state Intermediate state Present-day zebrafish hoxa1b Hoxa1 hoxa1a Ventral midbrain and hindbrain expression hoxa1a Non-functionalization hoxa1a Functional redundancy leads to "function shuffling" as hoxA1a loses hindbrain expression hoxb1b hoxb1b hoxb1b hoxb1a hoxb1a Hoxb1 Sub-functionalization Autoregulatory sequences 3′ RARE Putative midbrain domain regulatory elements Figure 3 | Function shuffling. Zebrafish hoxb1a and hoxb1b have expression profiles that are remarkably similar to those of mouse Hoxb1 and Hoxa1, respectively41. The early expression of mouse Hoxa1, like Hoxb1, is dependent on a 3′ retinoic-acid response element (3′ RARE), which transiently drives the expression of Hoxa1 in the developing hindbrain94,95. By contrast, the only zebrafish orthologue of mouse Hoxa1, zebrafish hoxa1a, is not expressed in the developing hindbrain, but only in the ventral midbrain41,96. Comparative analyses have indicated that this midbrain expression might be a primitive characteristic of Hoxa1, as it is shared by chick and Xenopus91,97. In the zebrafish, hoxb1b has taken on the hindbrain patterning role of tetrapod Hoxa1, which has possibly freed hoxa1a to lose its hindbrain expression domain, while retaining the ancestral midbrain patterning role. This function shuffling relies on a phase of partial functional redundancy between non-orthologous genes, in this case hoxa1a and hoxb1b. These experiments reveal the importance of studying an entire group of duplicated genes to understand fully the consequences of a duplication event. Furthermore, function shuffling might prove to be common among teleost paralogues. For example, it has recently been shown using morpholino-based knock-down experiments that the zebrafish engrailed2a and engrailed2b genes have early developmental roles that are equivalent to that of the non-orthologous mouse Engrailed 1 (En1) gene98. Modified with permission from REF. 91 © (2002) Elsevier Science. RHOMBOMERE A segment of the vertebrate hindbrain (rhombencephalon). MORPHOLINO An antisense reagent that is able to block translation to knock down gene function. TETRASOMY When one chromosome in the complement is represented four times in each nucleus. ORTHOLOGUES Homologous genes that are related by a speciation event. For example, mouse Hoxa1 and chick HOXA1 are orthologues. 832 is instead required for the correct segmental organization of the hindbrain40. This segmentation function of hoxb1b is shared with mouse Hoxa1 (REFS 45–47). How did the function of a HoxA gene shift to a HoxB gene? We suggest that the extensive redundancy found between paralogue group 1 genes (which are the result of a series of duplication events) has allowed “function shuffling” to occur (FIG. 3). The duplication event that led to extra Hox clusters in zebrafish was probably a part of a whole-genome duplication. Evidence for this genome duplication comes from mapping and sequencing data, coupled with phylogenetic analysis7,33,48,49. About 20% of the duplicates that arose from this event have been retained7. To clarify, the zebrafish is not a tetraploid organism. Unlike species that have undergone recent duplications, such as salmonid fishes50, there is no evidence for TETRASOMY in zebrafish. Although many duplicated zebrafish genes have been retained, they are no longer strictly equivalent genes showing complete redundancy; instead, their initial redundancy has been partially resolved in ways that can provide new insight into the functions of the ancestral gene. An interesting example is provided by the duplicated microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (Mitf) genes. The Mitf genes are required for the formation of pigment cells, with different mutations in the single human gene leading to syndromes that affect sensory systems and pigmentation (Waardenburg syndrome type 2a (REF. 51) or Tietz syndrome52). The single mouse Mitf gene is characterized by several splice variants; mutation of this gene leads to a loss of pigmented neural-crest-derived melanocytes, as well as to a loss of retinal pigment epithelium53. In zebrafish, there are two mitf genes, mitfa and mitf b. A mutant in mitfa (the nacre mutant) causes an absence of crest-derived melanocytes; however, despite expression of mitfa in retinal epithelium, this tissue is intact in nacre fish. This observation led Lister and colleagues54 to search for and find the mitf b duplicate gene, which they showed is expressed with mitfa in the retina. Although the duplicates share significant sequence identity, the mitfb gene includes an alternative 5′ exon, such that the two duplicates together recapitulate both the expression patterns and the two distinct isoforms of their mammalian ORTHOLOGUE. Furthermore, the two mitf genes do not behave identically in their ability to functionally rescue the nacre mutant, which indicates that tissue-specific alternative splice products of a single ancestral gene have been converted into two genes with distinct properties. Like the Hox genes, duplicated mitf genes have been found in several teleosts; the expression and sequence | NOVEMBER 2002 | VOLUME 3 www.nature.com/reviews/genetics © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS ORGANIZER A small dorsal region of the vertebrate gastrula-stage embryo that has the remarkable capacity to organize a complete embryonic body plan. Hilde Mangold and Hans Spemann first identified the organizer in amphibian embryos using tissue transplantation. MADS BOX A highly conserved sequence motif found in a family of plant transcription factors and named after the initials of the four founder members of the family. MERISTEM An undifferentiated cell population that resides at the growing tip of the roots or shoots of a plant. analysis of mitf duplicates in the small teleost Xiphophorus maculatus indicates that sub-functionalization occurred in the common ancestor of Xiphophorus and zebrafish55. The zebrafish is a powerful genetic model system, and high-throughput mutagenesis approaches have already produced hundreds of mutations in genes that are required for crucial developmental processes56. The existence of functionally complementary duplicates in this species turns out to be a help to genetic analysis rather than a hindrance, because the pleiotropy of each gene is reduced, which facilitates their study. For example, squint (sqt ; now called nodal-related 1, ndr1) and cyclops (cyc) are zebrafish mutants in two duplicated nodal-class genes. Analysis of these individual and double mutant phenotypes has helped to shed light on the complexities of function of the single mouse nodal gene57,58. The ndr1 gene is expressed maternally, whereas cyc is a zygotic transcript, but the two act partially redundantly during the establishment of the ORGANIZER, and in the formation of both endoderm and mesoderm. The cyc gene also has a late function in the patterning of the neural plate. This requirement is only revealed genetically because ndr1 provides an early embryonic nodal signal, allowing the embryo to develop to the point at which the cyc requirement is revealed. This late requirement for nodal signalling is masked in the mouse by the early lethality of the nodal mutant. So, the partial redundancy shown between these duplicate zebrafish genes allows us to chart the likely sub-function organization of orthologous genes in other organisms. Another example is provided by the vertebrate Sox9 genes. Mutations in human SOX9 cause a complex condition known as campomelic dysplasia, which is characterized by extensive cartilage phenotypes and sex reversal. The early lethality of the homozygous condition has prevented the mechanism of SOX9 function in cartilage formation from being studied in detail either in the human or in a mouse model. Recently, Yan and colleagues59 established that a zebrafish Sox9 duplicate, sox9a, is mutated in the jellyfish mutant. Although this is a recessive-lethal mutation, the embryos develop to larval stages, which allows detailed analysis of cartilage phenotypes. The jellyfish mutant has revealed that Sox9 function is required for cartilage morphogenesis and differentiation, but not for the initial specification or migration of the neural crest cells from which the cartilage is derived. In this instance, the existence of duplicate genes has allowed the analysis of a homozygous mutant condition in zebrafish that could not be explored in other vertebrates. The partitioning of ancestral sub-functions between duplicate gene pairs by DDC mechanisms in the teleost lineage should continue to make mutant analysis in the zebrafish system a rewarding approach and to provide further insight into the details of the pleiotropic functions of human disease genes. Functional complementation in plants INFLORESCENCE MERISTEM An apical meristem that lies atop a shoot and that produces several, lateral flower meristems. Whereas whole-genome duplication occurs infrequently in animals, plants have adopted it as a routine. For example, many of the plants we depend on for food, such as maize and wheat, are ancient polyploids. Extensive gene duplication during the evolution of both maize60,61 and the mustard Arabidopsis thaliana1,62,63 has had a marked impact on the genes that regulate plant reproduction. The best estimates indicate that >35% of genes in these plants are preserved as duplicate copies16,61. One well-characterized example of partial redundancy, and apparent functional complementation, after gene duplication involves the APETALA1 (AP1), CAULIFLOWER (CAL) and FRUITFULL (FUL) genes of Arabidopsis. These genes all encode MADS-BOX-containing transcriptional regulators that have roles in the initial specification of flower MERISTEMS and the subsequent specification of floral organ primordia and later organ cell types64. AP1 and CAL have closely related sequences65 and are embedded in large regions of conserved synteny that are located on different arms of chromosome 1. They might be products of either an ancient linear duplication event, later separated by chromosome rearrangement, or polyploidization and translocation62,66. The FUL gene is more closely related to AP1 and CAL than to other Arabidopsis MADS-box genes, but its location on chromosome 5 indicates that it came to reside in the genome through a process of polyploidization. The three genes have between 55% and 75% identity in their amino-acid sequences in functionally defined regions, and their pattern of synteny in the Arabidopsis genome indicates that they might be good candidates for participating in DDC processes. The single, double and triple mutant phenotypes of severe hypomorphic or amorphic alleles of these genes indicate that functional complementation could explain their collective persistence in the genome. The single mutant phenotypes of ap1, cal and ful indicate independent roles for each gene in normal development. The most striking phenotype of severe ap1 loss-of-function homozygous alleles is the homeotic transformation of cells that contribute to the outer whorl organs of the flower (the sepals and petals) towards an INFLORESCENCE MERISTEM fate. This results in the ectopic production of whole-flower meristems and the eventual transformation of single flowers into multi-flower branches67 (FIG. 4). By contrast, homozygous cal mutant lines show little, if any, phenotype. Homozygotes for severe loss-offunction alleles of the ful gene produce defects in the cellular differentiation of the seed pod. The key collective role of the three genes in establishing flower meristem fate came to be appreciated when double and triple homozygous mutants were constructed9,64,68. Double homozygotes for ap1 and cal mutations have a markedly synergistic phenotype with characteristics not seen in single mutants. These plants fail to make the normal inflorescence-to-floral transition, instead producing large, highly ramified clusters of inflorescence meristems — reminiscent of the edible part of the cauliflower — that produce only occasional floral organs (FIG. 4). Triple mutants that lack all three of these gene activities completely fail to produce floral organs of any type under normal growth conditions. This result indicates that these three genes share a high level of interlocus functional redundancy and that this redundant activity stimulates meristems to begin the production of flowers. NATURE REVIEWS | GENETICS VOLUME 3 | NOVEMBER 2002 | 8 3 3 © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS Figure 4 | Mutant phenotypes of ap1 and ap1/cal plants. Scanning electron micrographs of Arabidopsis plants. From left to right: wild type; ap1/ap1 loss of function, showing a single flower without petals or STAMENS but with this tissue ‘homeotically’ transformed into three new flowers; a cal/cal;ap1/ap1 double mutant, in which flowers are replaced by ‘cauliflower’-like inflorescence meristems. STAMEN The male, pollen-bearing organ of the plant. ECOTYPE A subdivision of a species that survives as a distinct population through environmental selection and reproductive isolation. SYNONYMOUS CHANGE A nucleotide change that does not alter the amino acid that is encoded. REPLACEMENT ALLELE An allele in which a mutation causes a resulting change in amino-acid identity. 834 Expression studies that complement this mutational analysis hint at patterns of complementation that might have contributed to the genetic interactions now seen between the three genes. In mutants that lack AP1 activity, FUL RNA begins to accumulate in flower meristems at early stages. FUL is normally not expressed at such an early stage69, which implies the loss of a negative regulatory interaction between these genes. It is possible that an ancestral gene that has negative autoregulatory elements gave rise to one gene that retained a negative regulatory sub-function (FUL) and to another gene that has lost this sub-function through degenerative mutation (AP1). Intensive promoter analysis of Arabidopsis and outgroup MADS-box genes indicates that a scheme of initial subfunctionalization might be a logical hypothesis. To assert confidently that the Arabidopsis triple mutant (ap1/cal/ful ) phenotype recapitulates the phenotype that would be expected from the loss of a single ancestral gene, the functional analysis of orthologues in an array of related plants is required. Such phylogenetically driven analyses might reveal that the process of duplication and degeneration of sub-functions has led to the development of a gene regulatory network, underpinning both the establishment of reproduction and the developmental modularity of inflorescences and flowers. The DDC model indicates that the initial preservation of gene duplicates by sub-functionalization is followed by further degeneration of redundant subfunctions. This process, referred to as resolution, is anticipated to be completed in <5 million years (REF. 17), in most cases. Given this time frame, the continuing redundancy seen between the AP1, CAL and FUL genes is surprising as the last major duplication event in the Arabidopsis lineage occurred at least 65 Mya (REF. 1). So, the redundancy seen between these genes is difficult to explain simply from the standpoint of the DDC model. It is possible that AP1, CAL and FUL have regulatory regions with physically or functionally overlapping cisregulatory sites that have an impact on several functions of each gene17,22. This type of functional entanglement would violate the requirement of the DDC model that regulatory regions be independently mutable. Under this model, all three loci would be left with redundant regulatory regions that could not be resolved by subsequent rounds of mutation. Alternatively, it is possible that these genes have recently changed from a situation in which all three genes were under purifying or positive selection for their collective role to a position in which these selective constraints have been removed. If this model is correct, a “punctuated DDC” process might have ensued in which initial degeneration and complementation under a selective constraint was followed by a change in that selection, which led to reacquisition of functional redundancy and the subsequent accumulation of new degenerate alleles. A singularly powerful study by Purugganan and Suddith70 serves as a model to explore the population-level processes that affect redundant duplicates. Evidence from this study provides some support for a punctuated DDC process having an impact on these genes. A sequence survey of 17 CAL alleles that were isolated from 12 distinct Arabidopsis ECOTYPE populations showed that CAL is a highly polymorphic gene. A total of 21 polymorphisms were seen in exons, 16 of which caused non-synonymous changes at the amino-acid level and 5 of which were SYNONYMOUS. This is in contrast to a recent survey of 18 coding-region polymorphisms at the AP1 locus, in which 10 non-synonymous and 8 synonymous variants were observed71. This result should be treated with a measure of caution because of the potential for sequencing errors, but it nevertheless shows that there is an excess of REPLACEMENT ALLELES at CAL in Arabidopsis 72, indicating that this gene has been evolving in a non-neutral fashion in these populations. So, alleles in these ecotypes seem to have diversified under evolutionary selection. However, the generation of double homozygotes for AP1-null and CAL ecotype alleles revealed that at least two populations were fixed for severe loss-of-function alleles at the CAL locus. This indicates that the role of CAL as an active gene might be changing to that of a pseudogene, as FUL and AP1 act in its place. Alternatively, degenerative mutations might be leading to the fixation of non-functional CAL alleles in some populations and to alleles that complement FUL and AP1 activities in others, owing to a recent relaxation of selective constraints. As more becomes known about the regulation of all three genes, it will be interesting to expand the sequence analysis of polymorphic CAL alleles into the cis-regulatory regions and to test the functional equivalence of FUL and AP1 alleles from ecotypes with and without functional CAL. The general approach of using population-level assessments of allele polymorphism with the functional assessment of ‘natural’ alleles, through genetic or transgenic experiments, should shed more light on the evolving state of duplicate gene interactions. The promise of the genomic era As sub-functionalization might often depend on complementary degenerative changes in the cis-regulatory elements of duplicated genes, it might ultimately prove possible to recognize candidate cases of sub-functionalization on the basis of direct analysis of regulatory sequences. Recently, a large-scale sequence comparison of Hox clusters was carried out, which failed to produce | NOVEMBER 2002 | VOLUME 3 www.nature.com/reviews/genetics © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS CLADE A lineage of organisms or alleles that comprises an ancestor and all its descendants. strong evidence of sub-functionalization. Chiu and colleagues73 compared the complete HoxA clusters of species across the main jawed-vertebrate lineages (human, horn shark (a chondrichthyian fish), striped bass and zebrafish; FIG. 1) by using several sequencealignment tools, including the powerful Web-based software PipMaker (for percentage identity plot74; see Online link to PipMaker and MultiPipMaker). The PipMaker program aligns multiple large sequences and produces a readout that is easy to understand and that shows regions of homology where percentage identity exceeds 50%. Chiu and colleagues focused on short 100% conserved regions, called ‘phylogenetic footprints’, which they found occurred frequently in clusters that could span 200 nucleotides or more. Their comparisons showed that, although horn shark and human share large tracts of sequence identity, these were rarely conserved in the teleosts (zebrafish or striped bass). The analysis infrequently showed evidence of duplicated zebrafish Hox genes partitioning the phylogenetic footprints present in the horn shark or human (which are representative of the pre-duplication ancestral condition), which is apparently inconsistent with the DDC model. Instead, they suggested that their results indicate the action of adaptive modification on the duplicated Hox clusters. Santini and Meyer have carried out rather similar analyses, but obtained more evidence in support of the occurrence of DDC processes (S. Santini and A. Meyer, personal communication). These researchers again compared HoxA cluster sequences, incorporating data on the cichlid Oreochromis niloticus into their analysis. Similarly to Chiu and colleagues they used the PipMaker software, but they focused on longer “conserved non-coding sequences”, showing at least 60% identity over 50 nucleotides. They also made use of the TRANSFAC Web-based software (see Online link to TRANSFAC) to identify known transcription-factorbinding sites. This approach indicated the possibility of more extensive conservation of HoxA regulatory elements between all the vertebrates examined. Furthermore, in cases where two HoxA gene duplicates have both been retained in the zebrafish, the conserved regulatory elements were recognizable in both copies. However, these elements also showed some differences from one another, consistent with the action of DDC processes. Another comparative study, which focused on the Hoxb2–Hoxb3 intergenic region and used a broad array of sequence analysis tools, also revealed extensive homology between mammals and teleosts. The Hoxb2–Hoxb3 intergenic sequences of mouse, human, zebrafish, striped bass and pufferfish all share conserved cis-regulatory elements75. These conserved sequences are important for the proper expression of mouse Hoxb2 and, consistent with the conserved function of the elements, the expression patterns of the vertebrate Hoxb2 orthologues are also largely conserved. Interestingly, in several cases, the binding sites occur in different orders in different species, and such reorganization of small cis-regulatory elements might make it difficult for large-scale alignment tech- niques to detect all the sequences that are important for functional homology. More detailed analyses such as this might therefore hold promise for allowing candidate sub-functions to be recognized. On a note of caution, the conservation that has been detected at the sequence level for Hox-cluster regulatory elements might not reflect the situation with non-Hox genes. The Hox genes are subject to unusual constraints that have been powerful enough to maintain clustered organization over many millions of years. For other classes of genes, it might prove far more difficult to detect the sequences that produce conserved expression patterns because cis binding sites and transcription factor proteins can co-evolve. For example, the potential complexity and rapid evolution of cis-elements has been amply shown in a detailed comparison of the eve stripe 2 enhancers from the closely related drosophilids Drosophila melanogaster and D. virilis 76. Despite the conserved expression patterns of the eve genes in the two species, the enhancers have evolved rapidly, with compensatory changes occurring in each. A different complicating factor has occurred in the case of maize, in which transposons have made important contributions to regulatory sequences77. Such changes might make it difficult to recognize the complementary degenerative changes that should be the hallmark of sub-functionalization events, especially in cases of ancient duplications. An approach based on sequence analysis has also been taken by several groups to look at the coding regions of genes and to identify regional divergence that would be consistent with the DDC model78,79. To identify potential duplicates in a species’ genome, computational methods are used to identify likely members of gene families, to align nucleotide and amino-acid sequences and to reconstruct the molecular phylogeny of gene families using tree-building programs78. Terminal branches of CLADES with pairs of highly similar genes can indicate likely candidates for duplicates65, which in turn can be subjected to tests to identify regions with high or low relative rates of non-synonymous/replacement nucleotide changes. These relative rates can be used to determine whether aligned regions of closely related genes are diverging or are under purifying selection to maintain functional similarity in both genes80,81. The increasingly sophisticated functional and phylogenetic analyses of gene families identified from sequencing projects are already revealing potential redundancy and complementation between duplicates that arose from global and local duplication events82,83. Using amino-acid-sequence and nucleotide-sequence alignments, and the tools of molecular phylogeny, Gu78 has developed statistical methods to analyse all of the amino-acid sites from gene families between and within species that are undergoing statistically significant divergence. Using the DIVERGE software package (see Online link to DIVERGE software), each amino acid is assigned a probabilistic value based on its chemical type (for example, acidic or hydrophobic) and the severity of change compared with another sequence. The program can even map changes onto known three-dimensional structures NATURE REVIEWS | GENETICS VOLUME 3 | NOVEMBER 2002 | 8 3 5 © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS for proteins, to assess whether or not a change is occurring in a region of the protein with a known active site, a solvent-exposed region or a role in folding. As more structures become available, the ability to map patterns of functional complementation onto individual protein structures might provide evolutionary guidance to the biochemical and proteomic analysis of protein function. Concluding remarks What are the implications of the sub-functionalization model for evolution? One important concept is that once sub-functionalization has preserved duplicate genes in the genome, those genes will be under different selective pressures relative to their shared ancestor. This might enable duplicates to explore a mutational space that is closed to their shared ancestor. The differential resolution of functional overlap through degenerative complementation might also be important in speciation. For example, if duplicates from different subpopulations become unable to complement each other’s lost sub-functions, the two populations might no longer be able to interbreed when they are later reunited1,84. The larger the number of duplicated genes in the original population the more likely such differential resolution becomes. Future investigation of the sub-functionalization model will require an analysis of candidate subfunctionalized genes in a clear phylogenetic context. Knowledge of the common ancestor will be crucial for 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 836 Lynch, M. & Conery, J. S. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science 290, 1151–1155 (2000). This paper analyses divergence rates between duplicated genes from six eukaryotic genomes and argues that duplications might be important in speciation. Song, K., Lu, P., Tang, K. & Osborn, T. C. Rapid genome change in synthetic polyploids of Brassica and its implications for polyploid evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 7719–7723 (1995). Hughes, M. K. & Hughes, A. L. Evolution of duplicate genes in a tetraploid animal, Xenopus laevis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10, 1360–1369 (1993). Sidow, A. Gen(om)e duplications in the evolution of early vertebrates. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6, 715–722 (1996). Meyer, A. & Schartl, M. Gene and genome duplications in vertbrates: the one-to-four (-to-eight in fish) rule and the evolution of novel gene functions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 699–704 (1999). Wolfe, K. H. Yesterday’s polyploids and the mystery of diploidization. Nature Rev. Genet. 2, 333–341 (2001). Postlethwait, J. H. et al. Zebrafish comparative genomics and the origins of vertebrate chromosomes. Genome Res. 10, 1890–1902 (2000). Tautz, D. Redundancies, development and the flow of information. Bioessays 14, 263–266 (1992). Pickett, F. B. & Meeks-Wagner, D. R. Seeing double, appreciating genetic redundancy. Plant Cell 7, 1347–1356 (1995). Thomas, J. H. Thinking about genetic redundancy. Trends Genet. 9, 395–399 (1993). Fisher, R. A. The sheltering of lethals. Am. Nat. 69, 446–455 (1935). Haldane, J. B. S. The part played by recurrent mutation in evolution. Am. Nat. 67, 5–9 (1933). Nadeau, J. H. & Sankoff, D. Comparable rates of gene loss and functional divergence after genome duplications early in vertebrate evolution. Genetics 147, 1259–1266 (1997). Li, W. H., Gu, Z., Wang, H. & Nakrutenko, A. Evolutionary analyses of the human genome. Nature 409, 847–849 (2001). applying rigorous tests, in which gene expression, function, regulation and sequence evolution can be analysed to piece together the evolutionary history of duplicates. At present, the two examples that most closely approach complete tests of the sub-functionalization model are the analyses of the zebrafish mitf and hoxb1 duplicate genes (as previously discussed). Zebrafish and other teleost fishes, as well as plants, will continue to provide useful models in which to investigate DDC processes because of their relatively recent duplications and the ease with which they can be manipulated genetically in the lab. More experimental data will also allow increasingly sophisticated theoretical models to be generated. These might have predictive value, such that, in the long term, candidate subfunctionalized genes might be recognizable simply on the basis of sequence analysis. Finally, the sub-functionalization model allows a new appreciation of the concepts of redundancy and multifunctionality. For many researchers, redundancy has been considered something of a problem. Theoreticians have grappled with explaining why redundancy occurs. Mouse molecular geneticists have been frustrated to find that knockout alleles do not always produce a phenotype. A consideration of genes as the sum of their sub-functions might ultimately help us to understand both redundancy and the informational networks that support genetic and phenotypic modularity. 15. Bailey, J. A. et al. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science 297, 1003–1007 (2002). 16. The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815 (2000). 17. Force, A. et al. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics 151, 1531–1545 (1999). The original description of the DDC subfunctionalization model is reported here. 18. Lynch, M. & Force, A. The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics 154, 459–473 (2000). 19. Edelman, G. M., Meech, R., Owens, G. C. & Jones, F. S. Synthetic promoter elements obtained by nucleotide sequence variation and selection for activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 3038–3043 (1999). 20. Yuh, C. H., Bolouri, H. & Davidson, E. H. Cis-regulatory logic in the endo16 gene: switching from a specification to a differentiation mode of control. Development 128, 617–629 (2001). 21. Carroll, S. B. Endless forms: the evolution of gene regulation and morphological diversity. Cell 101, 577–580 (2000). 22. Force, A., Cresko, W. F. & Pickett, F. B. in Modularity in Development and Evolution (eds Schlosser, G. & Wagner, G.) (Univ. of Chicago Press, Illinois, in the press). 23. Piatigorsky, J. & Wistow, G. The recruitment of crystallins: new functions precede gene duplication. Science 252, 1078–1079 (1991). 24. Hughes, A. L. The evolution of functionally novel proteins after gene duplication. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 256, 119–124 (1994). 25. Averof, M., Dawes, R. & Ferrier, D. Diversification of arthropod Hox genes as a paradigm for the evolution of gene functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 7, 539–551 (1996). 26. Stoltzfus, A. On the possibility of constructive neutral evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 49, 169–181 (1999). 27. Lynch, M., O’Hely, M., Walsh, B. & Force, A. The probability of preservation of a newly arisen gene duplicate. Genetics 159, 1789–1804 (2001). 28. Castillo-Davis, C. I. & Hartl, D. L. Genome evolution and developmental constraint in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 728–735 (2002). | NOVEMBER 2002 | VOLUME 3 29. Seoighe, C. & Wolfe, K. H. Updated map of duplicated regions in the yeast genome. Genes Dev. 238, 253–261 (1999). 30. McGinnis, W. & Krumlauf, R. Homeobox genes and axial patterning. Cell 68, 283–302 (1992). 31. De Rosa, R. et al. Hox genes in brachiopods and priapulids and protostome evolution. Nature 399, 772–776 (1999). 32. Holland, P. W., Garcia-Fernandez, J., Williams, N. A. & Sidow, A. Gene duplications and the origins of vertebrate development. Development (Suppl.), 125–133 (1994). 33. Amores, A. et al. Genome duplications in vertebrate evolution: evidence from zebrafish Hox clusters. Science 282, 1711–1714 (1998). This study analysed the complete organization of the zebrafish Hox clusters, providing strong evidence for the occurrence of a whole-genome duplication event during teleost evolution. 34. Manley, N. R. & Capecchi, M. R. The role of Hoxa-3 in mouse thymus and thyroid development. Development 121, 1989–2003 (1995). 35. Chisaka, O. & Capecchi, M. R. Regionally restricted developmental defects resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse homeobox gene hox-1.5. Nature 350, 473–479 (1991). 36. Condie, B. G. & Capecchi, M. R. Mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of Hoxd-3 (Hox-4.1) exhibit anterior transformations of the first and second cervical vertebrae, the atlas and the axis. Development 119, 579–595 (1993). 37. Condie, B. G. & Capecchi, M. R. Mice with targeted disruptions in the paralogous genes hoxa-3 and hoxd-3 reveal synergistic interactions. Nature 370, 304–307 (1994). 38. Greer, J. M., Puetz, J., Thomas, K. R. & Capecchi, M. R. Maintenance of functional equivalence during paralogous Hox gene evolution. Nature 403, 661–665 (2000). An elegant mouse genetics approach to investigating functional redundancy in Hox genes. 39. Bruce, A., Oates, A., Prince, V. E. & Ho, R. K. Additional hox clusters in the zebrafish: divergent expression belies conserved activities of duplicate hoxB5 genes. Evol. Dev. 3, 127–144 (2001). 40. McClintock, J. M., Kheirbek, M. A. & Prince, V. E. Knockdown of duplicated zebrafish hoxb1 genes reveals distinct www.nature.com/reviews/genetics © 2002 Nature Publishing Group REVIEWS 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. roles in hindbrain patterning and a novel mechanism of duplicate gene retention. Development 129, 2339–2354 (2002). Describes the sub-functionalization of a pair of duplicated zebrafish Hox genes. This study is unique in including the analysis of not only duplicate gene expression and function, but also duplicate regulatory sequences. McClintock, J. M., Carlson, R., Mann, D. M. & Prince, V. E. Consequences of Hox gene duplication in the vertebrates: an investigation of the zebrafish Hox paralogue group 1 genes. Development 128, 2471–2484 (2001). Studer, M., Lumsden, A., Ariza-McNaughton, L., Bradley, A. & Krumlauf, R. Altered segmental identity and abnormal migration of motor neurons in mice lacking Hoxb1. Nature 384, 630–634 (1996). Goddard, J. M., Rossel, M., Manley, N. R. & Capecchi, M. R. Mice with targeted disruption of Hoxb1 fail to form the motor nucleus of the V11th nerve. Development 122, 3217–3228 (1996). Gaufo, G. O., Flodby, P. & Capecchi, M. R. Hoxb1 controls effectors of sonic hedgehog and Mash1 signaling pathways. Development 127, 5343–5354 (2000). Lufkin, T., Dierich, A., LeMeur, M., Mark, M. & Chambon, P. Disruption of the Hox-1.6 homeobox gene results in defects in a region corresponding to its rostral domain of expression. Cell 66, 1105–1119 (1991). Carpenter, E. M., Goddard, J. M., Chisaka, O., Manley, N. R. & Capecchi, M. R. Loss of Hox-A1 (Hox-1.6) function results in the reorganization of the murine hindbrain. Development 118, 1063–1075 (1993). Mark, M. et al. Two rhombomeres are altered in Hoxa1 mutant mice. Development 119, 319–338 (1993). Postlethwait, J. H. et al. Vertebrate genome evolution and the zebrafish gene map. Nature Genet. 18, 345–349 (1998). Taylor, J. S., Van de Peer, Y., Braasch, I. & Meyer, A. Comparative genomics provides evidence for an ancient genome duplication event in fish. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356, 1661–1679 (2001). Sakamoto, T. et al. A microsatellite linkage map of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) characterized by large sexspecific differences in recombination rates. Genetics 15, 1331–1345 (2000). Tassabehji, M., Newton, V. E. & Read, A. P. Waardenburg syndrome type 2 caused by mutations in the human microphthalmia (MITF) gene. Nature Genet. 8, 251–255 (1994). Smith, S. D., Kelley, P. M., Kenyon, J. B. & Hoover, D. Tietz syndrome (hypopigmentation/deafness) caused by mutation of MITF. J. Med. Genet. 37, 446–448 (2000). Hodgkinson, C. A. et al. Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic helix–loop–helix zipper protein. Cell 74, 395–404 (1993). Lister, J. A., Close, J. & Raible, D. W. Duplicate mitf genes in zebrafish: complementary expression and conservation of melanogenic potential. Dev. Biol. 237, 333–344 (2001). Shows that the zebrafish mitfa and mitfb duplicate genes are homologous to distinct isoforms of the mammalian Mitf gene. Altschmied, J. et al. Subfunctionalization of duplicate mitf genes associated with differential degeneration of alternative exons in fish. Genetics 161, 259–267 (2002). Talbot, W. S. & Hopkins, N. Zebrafish mutations and functional analysis of the vertebrate genome. Genes Dev. 14, 755–762 (2000). Sampath, K. et al. Induction of the zebrafish ventral brain and floorplate requires cyclops/nodal signalling. Nature 395, 185–189 (1998). Feldman, B. et al. Zebrafish organizer development and germ-layer formation require nodal-related signals. Nature 395, 181–185 (1998). Yan, Y.-L. et al. A zebrafish sox9 gene is required for cartilage morphogenesis. Development (in the press). Gaut, B. S. & Doebley, J. F. DNA sequence evidence for the segmental allotetraploid origin of maize. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 6809–6814 (1997). Gaut, B. S. Patterns of chromosomal duplication in maize and their implications for comparative maps of the grasses. Genome Res. 11, 55–66 (2001). Vision, T. J., Brown, D. G. & Tanksley, S. D. The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science 290, 2114–2116 (2000). 63. Blanc, G., Barakat, A., Guyot, R., Cooke, R. & Delseny, M. Extensive duplication and reshuffling in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant Cell 12, 1093–1101 (2000). 64. Ferrandiz, C., Gu, Q., Martienssen, R. & Yanofsky, M. F. Redundant regulation of meristem identity and plant architecture by FRUITFULL, APETALA1, and CAULIFLOWER. Development 127, 725–734 (2000). This report describes the phenotypes of triple mutants of the Arabidopsis genes AP1, CAL and FUL and their partially redundant functions in a gene network. 65. Purugganan, M. D., Rounsley, S. D., Schmidt, R. J. & Yanofsky, M. F. Molecular evolution of flower development: diversification of the plant MADS-box regulatory gene family. Genetics 140, 345–356 (1995). 66. Achaz, G., Netter, P. & Coissac, E. Study of intrachromosomal duplications among the eukaryote genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 2280–2288 (2001). 67. Irish, V. F. & Sussex, I. M. Function of the apetala-1 gene during Arabidopsis floral development. Plant Cell 2, 741–753 (1990). 68. Bowman, J. L., Alvarez, J., Weigel, D., Meyerowitz, E. M. & Smyth, D. R. Control of flower development in Arabidopsis thaliana by APETALA1 and interacting genes. Development 119, 721–743 (1993). 69. Mandel, M. A. & Yanofsky, M. F. The Arabidopsis AGL8 MADS box gene is expressed in inflorescence meristems and is negatively regulated by APETALA1. Plant Cell 7, 1763–1771 (1995). 70. Purugganan, M. D. & Suddith, J. I. Molecular population genetics of the Arabidopsis CAULIFLOWER regulatory gene: nonneutral evolution and naturally occurring variation in floral homeotic function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 9, 8130–8134 (1998). Describes sequence comparisons of MADS-box genes from ecotypes of Arabidopisis to reveal that CAL is a surprisingly polymorphic gene. 71. Olsen, K. M., Womack, A., Garrett, A. R., Suddith, J. I. & Purugganan, M. D. Contrasting evolutionary forces in the Arabidopsis thaliana floral developmental pathway. Genetics 160, 1641–1650 (2002). 72. McDonald, J. H. & Kreitman, M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature 351, 652–654 (1991). 73. Chiu, C.-H. et al. Molecular evolution of the HoxA cluster in the three major gnathostome lineages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5492–5497 (2002). 74. Schwartz, S. et al. PipMaker — A web server for aligning two genomic DNA sequences. Genome Res. 10, 577–586 (2000). 75. Scemama, J.-L., Hunter, M., McCallum, J., Prince, V. & Stellwag, E. Evolutionary divergence of teleost Hoxb2 expression patterns and transcriptional regulatory loci. J. Exp. Zool. 294, 285–299. 76. Ludwig, M. Z., Bergman, C., Patel, N. H. & Kreitman, M. Evidence for stabilizing selection in a eukaryotic enhancer element. Nature 403, 564–567 (2000). 77. Zhang, Q., Arbuckle, J. & Wessler, S. R. Recent, extensive, and preferential insertion of members of the miniature inverted-repeat transposable element family Heartbreaker into genic regions of maize. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 1160–1165 (2000). 78. Gu, X. Statistical methods for testing functional divergence after gene duplication. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1664–1674 (1999). 79. Dermitzakis, E. T. & Clark, A. G. Differential selection after duplication in mammalian developmental genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 557–562 (2001). 80. Nei, M. & Kumar, S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2000). 81. Kumar, S., Tamura, K., Jakobsen, I. B. & Nei, M. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17, 1244–1245 (2001). 82. Shuai, B., Reynaga-Pena, C. G. & Springer, P. S. The lateral organ boundaries gene defines a novel, plant-specific gene family. Plant Physiol. 129, 747–761 (2002). 83. Shiu, S. H. & Bleecker, A. B. Receptor-like kinases from Arabidopsis form a monophyletic gene family related to animal receptor kinases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10763–10768 (2001). 84. Lynch, M. & Force, A. Gene duplication and the origin of interspecific genomic incompatibility. Am. Nat. 156, 590–605 (2000). NATURE REVIEWS | GENETICS 85. Mezey, J. G., Cheverud, J. M. & Wagner, G. P. Is the genotype–phenotype map modular? A statistical approach using mouse quantitative trait loci data. Genetics 156, 305–311 (2000). 86. Emerson, R. A. Genetic correlation and spurious allelomorphism in maize. Nebraska Agric. Exp. Stat. Annu. Rep. 24, 59–90 (1911). 87. Muller, H. J. Further studies on the nature and causes of gene mutations. Proc. Sixth Int. Congr. Genet. 1, 213–255 (1932). 88. Serebrovsky, A. S. & Dubinin, N. P. Artificial production of mutations and the problem of the gene. Uspeki Eksperimental noi Biologii 8, 235–247 (1929). 89. Raffel, D. & Muller, H. J. Position effect and gene divisibility considered in connection with three strikingly similar scute mutations. Genetics 25, 541–583 (1940). 90. Verderosa, F. J. & Muller, H. J. Another case of dissimilar characters in Drosophila apparently representing changes of the same locus. Genetics 39, 999 (1954). 91. Prince, V. E. The Hox paradox: more complex(es) than imagined. Dev. Biol. 249, 1–15 (2002). 92. Studer, M. et al. Genetic interactions between Hoxa1 and Hoxb1 reveal new roles in regulation of early hindbrain patterning. Development 125, 1025–1036 (1998). 93. Pöpperl, H. et al. Segmental expression of Hoxb1 is controlled by a highly conserved autoregulatory loop dependent upon exd/pbx. Cell 81, 1031–1042 (1995). 94. Dupe, V. et al. In vivo functional analysis of the Hoxa-1 3′ retinoic acid response element (3′RARE). Development 124, 399–410 (1997). 95. Langston, A. W., Thompson, J. R. & Gudas, L. J. Retinoic acid-responsive enhancers located 3′ of the Hox A and Hox B homeobox gene clusters. Functional analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 2167–2175 (1997). 96. Shih, L., Tsay, H., Lin, S. & Hwang, S. L. Expression of zebrafish Hoxa1a in neuronal cells of the midbrain and anterior hindbrain. Mech. Dev. 101, 279–281 (2001). 97. Kolm, P. J. & Sive, H. L. Regulation of the Xenopus labial homeodomain genes, HoxA1 and HoxD1: activation by retinoids and peptide growth factors. Dev. Biol. 167, 34–49 (1995). 98. Scholpp, S. & Brand, M. Morpholino-induced knockdown of zebrafish engrailed genes eng2 and eng3 reveals redundant and unique functions in midbrain–hindbrain boundary development. Genesis 30, 129–133 (2001). Acknowledgements We thank A. Bruce, A. Force, R. Ho, J. Postlethwait and three reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. We are also grateful to D. Raible for advice on Mitf gene evolution, and to S. Santini and A. Meyer for sharing their observations before publication. Work cited from the Prince lab was funded by the National Science Foundation and that from the Pickett lab by the National Institutes of Health. Online links DATABASES The following terms in this article are linked online to: LocusLink: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/LocusLink Abd-B | dumpy | En1 | eve stripe 2 | Hoxa1 | Hoxa3 | Hoxb1 | hoxb1a | hoxb1b | Hoxb2 | Hoxb3 | hoxb5a | Hoxd3 | Mitf | nodal | os | Sox9 | SOX9 | Sy OMIM: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim campomelic dysplasia | Tietz syndrome | Waardenburg syndrome type 2a The Arabidopsis Information Resource: AP1 | CAL | FUL ZFIN: http://zfin.org cyc | egr2 | engrailed2a | engrailed2b | mitfa | mitfb | ndr1 | sox9a FURTHER INFORMATION DIVERGE software: http://xgu1.zool.iastate.edu F. Bryan Pickett’s lab: http://www.luc.edu/depts/biology/pickett.htm Gene Tools LLC: http://www.gene-tools.com PipMaker and MultiPipMaker: http://bio.cse.psu.edu/pipmaker TRANSFAC — The Transcription Factor Database: http://transfac.gbf.de/TRANSFAC Victoria Prince’s lab: http://pondside.uchicago.edu/oba/faculty/prince_v.html Access to this interactive links box is free online. VOLUME 3 | NOVEMBER 2002 | 8 3 7 © 2002 Nature Publishing Group