* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Ask a Geneticist

Cre-Lox recombination wikipedia , lookup

Epigenetics of neurodegenerative diseases wikipedia , lookup

Transposable element wikipedia , lookup

No-SCAR (Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering) Genome Editing wikipedia , lookup

Hybrid (biology) wikipedia , lookup

DNA supercoil wikipedia , lookup

Cancer epigenetics wikipedia , lookup

Pathogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Oncogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Skewed X-inactivation wikipedia , lookup

Genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Vectors in gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

Nutriepigenomics wikipedia , lookup

Non-coding DNA wikipedia , lookup

Polycomb Group Proteins and Cancer wikipedia , lookup

Therapeutic gene modulation wikipedia , lookup

Human genome wikipedia , lookup

Ridge (biology) wikipedia , lookup

Genomic library wikipedia , lookup

Site-specific recombinase technology wikipedia , lookup

Genome editing wikipedia , lookup

Extrachromosomal DNA wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression profiling wikipedia , lookup

Helitron (biology) wikipedia , lookup

Minimal genome wikipedia , lookup

Genomic imprinting wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression programming wikipedia , lookup

Epigenetics of human development wikipedia , lookup

Y chromosome wikipedia , lookup

History of genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Genome evolution wikipedia , lookup

Designer baby wikipedia , lookup

Biology and consumer behaviour wikipedia , lookup

Neocentromere wikipedia , lookup

Artificial gene synthesis wikipedia , lookup

X-inactivation wikipedia , lookup

Genome (book) wikipedia , lookup

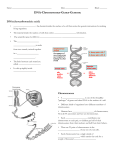

Ask a Geneticist by Dr. Bronwyn MacInnis, Stanford University Hi - I've recently become interested/fascinated by genetics; my basic question is:'why' is the [human] genome split into separate chromosomes rather than being one long strand and what determines[ed] which genes went to which chromosome? -A curious adult from the United Kingdom You’re right that these questions are basic. But this doesn’t mean they are simple. Sometimes the simplest questions about biology and genetics are the hardest to answer. To some extent the number of chromosomes and which genes are on each chromosome may be due to blind evolutionary chance. But that’s not the whole story… Why is the human genome split into separate chromosomes rather than being one long strand? First let me remind you that we humans have 46 chromosomes in each of our cells. So why 46 chromosomes? Why not one giant one? Some of the simplest forms of life, like bacteria, We have many chromosomes to keep all of their DNA in a single chromosome. increase our differences However, more complex creatures (like humans!) divide their DNA into lots of different chromosomes. One reason for this difference may have to do with how each kind of beast makes babies. Bacteria make new bacteria asexually. This means that when they make new bacteria, they just split in two with each half getting a copy of the same DNA. Most other creatures make new offspring sexually. What this does is combine DNA from two parents to make the child. We all have two copies of every chromosome (except males who have one X and one Y plus 22 other pairs). Mom and dad give us copies of half their DNA—one of each chromosome. At the end, we all have two copies of each of our chromosomes just like mom and dad. But our DNA is a mix of mom’s and dad’s. Each egg or sperm gets 23 chromosomes (half of each pair). Which chromosome they get in the pair is totally random. When you do the math, this comes out to 10 trillion different possible combinations. If we had only one pair of chromosomes, the number drops to 4. Of course, none of this would matter if the chromosomes were exactly the same between mom and dad. Luckily they’re not. In fact, there is on average 6 million differences between any two people’s DNA. The mixing of DNA in this way generates lots of these differences. This ‘genetic diversity’ is very important for survival. Not necessarily the survival of any one individual, but for the species as a whole. Say, for example, a new deadly disease hits (think of the plague during the Middle Ages). Lots of people would die, but some would live. Some of these survivors would live because they had the right set of DNA differences. And reproducing sexually increases genetic diversity hugely. Without it, we’d have to rely on random DNA changes which wouldn’t cause as much mixing. And random changes can cause lots of problems with “bad” mutations that mixing doesn’t. So this addresses the question of why we don’t simply have one long strand of DNA. We need more than one to increase genetic diversity. But why 46 exactly? How (or why) we ended up with exactly 46 chromosomes is somewhat of an evolutionary mystery. Generally speaking though, species that are closely related have a similar number of chromosomes. For example, chimpanzees and other great apes, our closest evolutionary cousins, have 48. Over time, pieces of chromosomes break off and stick to other chromosomes. Sometimes whole chromosomes stick to other chromosomes. At some point in the last 6-8 million years, two of our chromosomes fused together to make our chromosome 2. We know this because our chromosome 2 is really just two chimpanzee chromosomes fused together. It is this sort of rearrangement that helped to give our current number of chromosomes. As you can see from this example, this number is certainly not fixed, it can and does change. So similar species tend to have a similar number of chromosomes. But aside from this general rule there is very little rhyme or reason to how many chromosomes a species has. For example, the number doesn’t have to do with how complicated the species is. We have 46 chromosomes but a goldfish has 94, and a certain type of fern (Ophioglossum reticulatum) has 1,260. And it’s safe to say we’re more complex than a fern! What determines which genes are on which chromosome? This is another interesting question for which I’m afraid I don’t have a straightforward answer. To some extent it may be that which genes are on which chromosomes is the luck of the evolutionary draw. We know that chromosomes contain different genes or “chunks” of the genome. Genes are simply stretches of DNA that contain instructions in a 4 letter, 64 word code for making a protein. Proteins are the workers in the cell. Almost anything that needs doing is done by a protein. They carry our oxygen, help us see and even think! In bacteria, those simple organisms with only one chromosome, the genes are organized into groups based on what the genes do for a living. For example, all the genes needed to digest lactose, the sugar found in milk, are grouped together on the chromosome. When there is lactose around, all the genes can get used together. Our genes may have started out similarly a billion years ago or so. But then those rearrangements we talked about earlier started happening. Also, for reasons we won’t go into, virus-like DNA picked up genes and moved them around. The end result is that our genes started getting separated and moved around. In humans for example, the gene for alpha globin, a part of the hemoglobin protein that carries oxygen in red blood cells, is found on chromosome 16. However, the gene for beta globin, the other part of the hemoglobin protein, is found on chromosome 11. Of course, our genes aren’t just a jumbled mess. Some parts of our chromosomes are organized by function. The infamous Y chromosome contains all the genes needed for ‘maleness’. Since both males and females have X chromosomes, the genes for ‘femaleness’ are not grouped on the X chromosome but instead are spread throughout the genome. Chromosome rearrangements and gene hopping may make the order of our genes less organized. But there is another process at work that makes groups of genes that are more organized on our chromosomes. This is called ‘gene duplication’. Like it sounds, gene duplication is when a region of DNA on a chromosome containing a gene gets copied. This new version of the gene becomes part of the genome and lives very close to its parent gene on the chromosome (unless a rearrangement happens!). Gene duplication is one way that new genes are born. Over time, small changes build up in human DNA. These random changes, or mutations, occur differently in the DNA of each version of the gene. What can happen is that the mutations cause the two genes to evolve different jobs. After awhile, you end up with a new gene having a new function. But these two genes are near each other and usually do pretty similar sorts of jobs. This results in more organization as genes that are doing similar things are near each other. I hope these answers help you to understand a little bit about why our genes and chromosomes are set-up the way they are. As you can see, we scientists are just beginning to understand the answers to these very interesting and important questions ourselves. Thanks for asking!