* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Developmental, transcriptome, and genetic alterations associated

Long non-coding RNA wikipedia , lookup

Epigenetics of neurodegenerative diseases wikipedia , lookup

Vectors in gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Polycomb Group Proteins and Cancer wikipedia , lookup

Oncogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Pathogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative trait locus wikipedia , lookup

Therapeutic gene modulation wikipedia , lookup

Biology and consumer behaviour wikipedia , lookup

Nutriepigenomics wikipedia , lookup

Ridge (biology) wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression programming wikipedia , lookup

Site-specific recombinase technology wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

Genomic imprinting wikipedia , lookup

Minimal genome wikipedia , lookup

Genetically modified organism containment and escape wikipedia , lookup

Epigenetics of human development wikipedia , lookup

Artificial gene synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Genome evolution wikipedia , lookup

Genome (book) wikipedia , lookup

History of genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression profiling wikipedia , lookup

Designer baby wikipedia , lookup

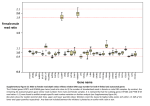

Journal of Experimental Botany, Vol. 67, No. 1 pp. 259–273, 2016 doi:10.1093/jxb/erv452 Advance Access publication 9 October 2015 RESEARCH PAPER Developmental, transcriptome, and genetic alterations associated with parthenocarpy in the grapevine seedless somatic variant Corinto bianco Carolina Royo1,*, Pablo Carbonell-Bejerano1,*,† Rafael Torres-Pérez1, Anna Nebish2, Óscar Martínez3, Manuel Rey3, Rouben Aroutiounian2, Javier Ibáñez1 and José M. Martínez-Zapater1 1 Instituto de Ciencias de la Vid y del Vino (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas-Universidad de La Rioja-Gobierno de La Rioja), Finca La Grajera, Carretera LO-20 - salida 13, Autovía del Camino de Santiago, 26007, Spain 2 Department of Genetics and Cytology, Yerevan State University, 1 Alex Manoogian str., 0025 Yerevan, Armenia 3 Departamento de Biología Vegetal y Ciencia del Suelo. Facultad de Biología. Universidad de Vigo, 36310 Vigo, Spain * These authors contributed equally to this work. To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected] † Received 7 July 2015; Revised 15 September 2015; Accepted 25 September 2015 Editor: Ariel Vicente Abstract Seedlessness is a relevant trait in grapevine cultivars intended for fresh consumption or raisin production. Previous DNA marker analysis indicated that Corinto bianco (CB) is a parthenocarpic somatic variant of the seeded cultivar Pedro Ximenes (PX). This study compared both variant lines to determine the basis of this parthenocarpic phenotype. At maturity, CB seedless berries were 6-fold smaller than PX berries. The macrogametophyte was absent from CB ovules, and CB was also pollen sterile. Occasionally, one seed developed in 1.6% of CB berries. Microsatellite genotyping and flow cytometry analyses of seedlings generated from these seeds showed that most CB viable seeds were formed by fertilization of unreduced gametes generated by meiotic diplospory, a process that has not been described previously in grapevine. Microarray and RNA-sequencing analyses identified 1958 genes that were differentially expressed between CB and PX developing flowers. Genes downregulated in CB were enriched in gametophyte-preferentially expressed transcripts, indicating the absence of regular post-meiotic germline development in CB. RNA-sequencing was also used for genetic variant calling and 14 single-nucleotide polymorphisms distinguishing the CB and PX variant lines were detected. Among these, CB-specific polymorphisms were considered as candidate parthenocarpy-responsible mutations, including a putative deleterious substitution in a HAL2-like protein. Collectively, these results revealed that the absence of a mature macrogametophyte, probably due to meiosis arrest, coupled with a process of fertilization-independent fruit growth, caused parthenocarpy in CB. This study provides a number of grapevine parthenocarpy-responsible candidate genes and shows how genomic approaches can shed light on the genetic origin of woody crop somatic variants. Key words: Diplospory, embryo sac, gametogenesis, grapevine, meiosis, microarray, parthenocarpy, pollen sterility, polyploidy, RNA-seq, seedlessness, SNP, somatic variation, transcriptomics, unreduced gamete, Vitis vinifera. Abbreviations: C, cytotype; CB, Corinto bianco; CB-SDD, Corinto bianco seeded; CB-SDL, Corinto bianco seedless; dba, days before anthesis; DEG, differentially expressed gene; ENC, Encín; FPKM, fragments per kb of exon per million fragments mapped; GRAJ, Grajera; PCA, principal component analysis; PX, Pedro Ximenes; RMA, robust multiarray average; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; TMM, trimmed mean of M-values; VALD, Valdegón. © The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Experimental Biology. All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: [email protected] 260 | Royo et al. Introduction Fruits appeared in angiosperms as innovative structures directed to protect and disseminate their sexual propagules, the seeds. Accordingly, fruit set is induced soon after fertilization, when developing seeds release growth substances to sporophytic tissues of the mother plant, generally carpellary tissues, triggering their development into a fruit (Dorcey et al., 2009; Sotelo-Silveira et al., 2014). Exceptionally, in parthenocarpic mutants, fruit development proceeds without fertilization, which results in seedless fruits. In contrast to facultative parthenocarpy, requiring an external intervention to avoid pollination/fertilization, obligatory parthenocarpic mutants are male and/or female sterile (Varoquaux et al., 2000). Although these mutants are not usually spread in nature due to their inability for sexual reproduction, seedlessness has been selected in many vegetatively propagated fruit crops as a highly desirable agronomic trait that allows easier fruit preparation and consumption by humans. Seedless variants are preferred as grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivars used for table grapes and raisin production. Given the high heterozygosity of the grapevine genome (Laucou et al., 2011), varietal characteristics are maintained through asexual propagation and thus a grapevine cultivar consists of an array of lines or clones descended by vegetative propagation from the original seedling (Pelsy, 2010). Asexual propagation of a cultivar over long periods favours the accumulation of somatic mutations, which sometimes give rise to plants showing new phenotypes (somatic variants) (Torregrosa et al., 2011). In this way, asexual propagation has enabled the appearance and maintenance of seedless grape variants. Two main mechanisms resulting in seedlessness have been identified among grapevine germplasm: (i) stenospermocarpy, in which there is fertilization and embryo formation but seed development aborts giving rise to seed traces; (ii) parthenocarpy, in which small berries without seed traces develop in the absence of fertilization (Stout, 1936; Varoquaux et al., 2000). The first variation is widely used in the production of seedless table grape cultivars because berry size is less compromised, while the second one is exploited in cultivars used for raisin production. Regardless of their genetic or geographical origin, parthenocarpic grapes used for dry fruit production are classically denominated Corinth (=Corinto=currant) grapes. Historical reports indicate that some current Corinth grape cultivars were cultivated by ancient Greeks (Weaver, 1960). Recent molecular analyses have elucidated that different Corinth cultivars including Black Corinth, Cape Currant, Corinto bianco, and Corinthe Blanc are not genetically related (Adam-Blondon et al., 2001; Vargas et al., 2007). Thus, independent somatic mutations affecting sexual reproduction are expected in different Corinth cultivars. In plants, successive mitosis of haploid cells produced by meiosis results in multicellular gametophytes, which is the basis for the double fertilization process (Chasan and Walbot, 1993). Female (macrogametophyte or embryo sac) and male (microgametophyte or pollen grain) gametophytes are produced in specialized sexual organs (ovule and anther, respectively). In grapevine, the female reproductive unit is a bicarpellary pistil with two anatropous ovules per locule, containing a Polygonum type embryo sac each (Pratt, 1971). The grapevine mature pollen is tricolpate and bicellular, consisting of a large vegetative cell and a small generative cell, which divides into two haploid sperm cells only after pollen germination (Cresti and Ciampolini, 1999). At fertilization, egg (haploid) and central (diploid) embryo sac cells each fuse with sperm cells giving rise to embryo and endosperm development, respectively, whereas seed coats develop from ovule sporophytic tissues. Failure of fertilization due to defects in any of these processes coupled with a capability for fertilization-independent fruit development is expected to occur in parthenocarpic grapes such as Corinth cultivars (Varoquaux et al., 2000). In fact, some extent of pollen sterility and occasional development of seeds, usually lacking embryos, was documented previously in certain Corinth cultivars (Pratt, 1971). Mutations responsible for parthenocarpy have been identified in fruit crops such as apple or tomato (Yao et al., 2001; Carrera et al., 2012). However, almost no information is available on the genetic basis of parthenocarpy in grapevine. A recent DNA microsatellite analysis identified Corinto bianco (CB) as a parthenocarpic seedless grape somatic variant of the white wine Spanish cultivar Pedro Ximenes (PX) (Vargas et al., 2007). Although the existence of macrogametogenesis alterations in CB was proposed previously (Pratt, 1971), the actual genetic and reproductive defects responsible for parthenocarpy of CB remain unknown. To investigate the developmental and genetic causes of seedlessness in CB, this study compared flower and fruit development between CB and its original seeded cultivar PX. Transcriptomic comparisons were directed to characterize the variant syndrome and to screen for mutations in candidate genes, involving either misregulation of gene expression or nucleotide sequence polymorphisms. Additionally, a genetic study of offspring obtained from infrequent CB seeds was useful to clarify their origin. Although the male and female sterility found in CB restricts the opportunities for genetic analysis, the overall results permitted us to postulate likely cytological and molecular explanations for the parthenocarpy of CB. Materials and methods Plant material All CB and PX plants used were grafted on Richter-110 rootstocks, trellized in double cordon Royat system, and cultivated in a similar way in three different grapevine plots (5–10 plants per cultivar and plot). Two plots belonged to the Grapevine Germplasm Collection of the Instituto de Ciencias de la Vid y del Vino (ICVV) (ESP217) and are maintained under the same agronomical conditions in two separate experimental locations: ‘Finca Valdegón’ (VALD) in Agoncillo (La Rioja, Spain) and ‘Finca La Grajera’ (GRAJ) in Logroño (La Rioja, Spain). Plants at GRAJ were grafted in 2010 from scions taken from VALD (20–30 years old). The third plot is the ‘Vitis Germplasm Bank’ (ESP-080) of the Instituto Madrileño de Investigación y Desarrollo Rural, Agrario y Alimentario (IMIDRA) located in ‘Finca El Encín’ (ENC) in Alcalá de Henares (Madrid, Spain) where PX and CB were planted in 2003 and 2004, respectively. Alterations associated with parthenocarpy in grapevine | 261 Morphometric analyses Fruit and seed features were characterized in both cultivars. Berry length and maximum diameter were estimated using an Absolute Digital Caliper (Mitutoyo, Japan). Berry and seed fresh weight were measured with a precision balance. The number of seeds per berry and the percentage of floating seeds were calculated in both cultivars, and the percentage of seeded berries only in CB (CB-SDD). Phenotyping analyses were carried out in three different seasons, 2011 at VALD, 2012 at VALD and ENC, and 2013 at GRAJ. 1962) supplemented with 20 g l–1 of sucrose, 1 µM gibberellic acid, 10 µM indoleacetic acid, 2.5 g l–1 of active charcoal and 8 g l–1 of agar. Plates were maintained at 23 °C under continuous illumination provided by cool white fluorescent tubes in a growth phytotron (Grow-RH, Ing. Climas, Barcelona, Spain). When true leaves developed, the seedlings were transplanted to a tube with growth medium without charcoal or hormones. After 1–2 months, the plants were transplanted to soil in pots, acclimated, and grown under field conditions at VALD. Macrogametogenesis analysis Ovule and macrogametophyte cytohistological observations were carried out on PX and CB flower buds (closed flowers) collected at VALD on 24/05/2011, at approximately 1 d before anthesis (dba), when few flowers of the same inflorescence were starting to open. Closed flowers were fixed in 37% formaldehyde, glacial acetic acid, 95% ethanol and water (10:5:50:35) at 4 °C. The material was resin embedded and sectioned in serial longitudinal and cross-sections, as described previously (Chevalier et al., 2014). Digital images were acquired with a Photometrics CoolSNAPcf camera connected to an Axioskop 2 plus microscopy (Zeiss, Germany). For each cultivar, the total number of ovules and number of ovules with a mature embryo sac per pistil were counted in sections of 70 and 30 flowers, respectively, collected weekly in 2013 at GRAJ between inflorescence swelling and anthesis stages, fixed with formalin/acetic acid/alcohol, and treated by common cytohistological techniques for sectioning after paraffin embedding (Ruzin, 1999). Microsatellite genotyping Young leaves were used for DNA extraction using a DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). They were genotyped for nine unlinked microsatellite loci, as described previously (Ibáñez et al., 2009). Microgametogenesis analysis Pollen viability was analysed in PX and CB over 3 consecutive years using Alexander’s modified staining (Peterson et al., 2010). Pollen was collected from inflorescences at 50% bloom and more than 1000 pollen grains per three biological replicates were analysed each year. Pollen germination was evaluated in vitro in 2014. Fresh pollen was collected from slightly opened flowers at anthesis and was sown immediately. Pollen grains were spread in germination medium (10% sucrose and 100 ppm boric acid dissolved in deionized water and solidified with 2% agar) on 40 × 12 mm uncovered Petri dishes, which were placed floating in humid chambers and incubated for 16 h at 25 °C. Pollen grains were considered germinated when the length of the pollen tube was more than twice the diameter of the pollen grain (>500 grains per three biological replicates per genotype were analysed). Images of pollen viability and germination assays were taken using an AxioCam camera (Zeiss) connected to a SteREO Discovery.V20 stereo-microscope (Zeiss) and were analysed using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012). Statistical analysis of phenotypic data One-way ANOVA was conducted to test for significant differences between PX, CB-SDD and CB seedless (CB-SDL) berry measures. Games–Howell was used as a post hoc test because variances were unequal according to Levene’s tests. A t-test was performed for twoclass comparisons. A significance level of P<0.01 was set in all cases. Every statistical test was performed using SPSS software (v.19.0 for Windows; IBM Corp., Somers, NY, USA). In vitro embryo rescue Every CB-SDD berry identified from VALD in 2011 was collected, as well as from all three plots in 2012 and 2013. Berries were sterilized before seed extraction by consecutively washing with Tween 20 diluted in water, 70% ethanol, and 1.5% sodium hypochlorite for 13 min and rinsed three times with sterilized distilled water. Seeds were cut at the distal extreme and sown on sterile Petri plates containing half-strength MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, Ploidy analysis Fresh young leaves were treated as described previously (Acanda et al., 2013), with minor modifications. Briefly, 50 mg of leaves was chopped with a sharp razor blade in 0.5 ml of 0.5× WPB buffer (Loureiro et al., 2007) and 1 ml of the same buffer was added. The homogenate was filtered through a 50 μM nylon mesh and incubated with 50 μg ml–1 of RNase (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 μg ml–1 of propidium iodide for 10 min. The resulting samples were analysed using an FC500 cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, USA) in 2013 and a BD Accuri C6 cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA) in 2014 to estimate the cytotype (C). Transcriptomic analysis RNA extraction Total RNA was extracted from frozen flower buds using a Spectrum™ Plant Total RNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich). An in-column DNase digestion step with the RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen) was added. Microarrays Three biological replicates of CB and PX flowers at 1 dba were hybridized to NimbleGen microarrays. Inflorescences collected from different VALD plants on 24/05/2011 were used for each replicate. Synthesis, labelling, and hybridization of cDNA to NimbleGen microarray 090818 Vitis exp HX12 (NimbleGenRoche) and robust multiarray average (RMA) normalization were performed as indicated elsewhere (Carbonell-Bejerano et al., 2014). Linear models for microarray data (limma) were run in Babelomics (Medina et al., 2010) to search for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between CB and PX. DEGs were identified considering a Benjamini–Hochberg corrected P≤0.05 and ≥2-fold change as significance thresholds. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis Six libraries were constructed from three replicates of CB and PX flowers at 10 dba. Inflorescences collected from different VALD plants on 23/05/2012 were used for each replicate. Libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Prep kit starting from 1 µg of total RNA. The adapter-ligated library was amplified with 15 PCR cycles, followed by purification with Ampure beads. Finally, the libraries were run on a Bioanalyser DNA1000 chip and quantified using a real-time PCR kit (Kapa Biosciences). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 using v.3 chemistry (flowcells and sequencing reagents). Paired-end strandspecific reads of 101 nt were produced. Gapped alignment of reads to the PN40024 12× grapevine reference genome assembly (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/GenomeBrowser/Vitis/) was carried out using TopHat2 v.2.0.13 (Kim et al., 2013). Only uniquely mapped single copy, ≤1 polymorphism per 25 bp reads with quality ≥20, paired in the expected orientation and aligned with a maximum insert size of 10 078 [mean fragment size in the libraries (277 bp)+95 percentile of gene size in the PN40024 12× V1 genome assembly (9801 bp)] were kept for further analysis. The htseq-count tool (v.0.5.4p5) from HTSeq (Anders et al., 262 | Royo et al. 2015) was used to estimate unambiguous read count per 12× V1 annotated transcript. Normalization following the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) method (Robinson and Oshlack, 2010), as well as a CB versus PX DEGs search (adjusted Benjamini– Hochberg P≤0.05 and ≥2-fold change) were performed in edgeR v.2.2.6 (Robinson et al., 2010). Finally, fragments per kb of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) was calculated using Cuffdiff v.2.2.1 (Trapnell et al., 2013) and low-expressed transcripts were filtered out when FPKM was <1 in both samples. Reads aligned to DEGs were inspected visually for allele-specific expression with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software (Thorvaldsdóttir et al., 2012). Principal component analysis (PCA) PCA was directed using Qlucore Omics Explorer v.3.0 (Lund, Sweden). The RMAnormalized signal and BAM format alignments from NimbleGen microarray and RNA-seq experiments, respectively, were used as input data. Functional analysis DEGs at 10 and 1 dba were compared using Venny (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/). The obtained gene lists were further analysed for functional enrichment in comparison with the whole set of transcripts predicted in the 12× V1 annotation of the grapevine reference genome following a grapevine-specific functional classification (Grimplet et al., 2012). The analysis was carried out in FatiGO, as described elsewhere (Carbonell-Bejerano et al., 2014). Additionally, enrichment meta-analysis of DEG lists in organ-specific genes and floral organ-detected genes, considered accordingly to the expression atlas published in the cultivar Corvina (Fasoli et al., 2012), were performed in FatiGO following the same procedures described above. Database deposit The microarray and RNA-seq data have been deposited in NCBI under Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) GSE69282 and Sequence Read Archive SRP058799 (BioProject PRJNA285072) accession numbers, respectively. Search for sequence polymorphisms To detect polymorphisms [single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions] between CB or PX and the PN40024 12× reference genome, RNA-seq alignments used for differential expression analysis were also analysed with the variant caller utility implemented in the SAMtools package v.0.1.18 (Li et al., 2009). Alignments in all three replicates of the same cultivar were analysed simultaneously. Then, to identify differential polymorphisms between CB and PX, the sequence of polymorphic sites identified in one cultivar was compared with the sequence at the same position in the other cultivar following ad hoc Bash shell and Perl scripts (Supplementary File S1, available at JXB online). Briefly, filters for the average depth per replicate (≥10 counts) and frequency for cultivar-distinctive alleles (≥35%), and a frequency of spurious alleles of <2.5% in both samples, were set. In addition, only polymorphisms confirmed in all replicates after checking in IGV software were considered. The effect of detected polymorphisms considering grapevine 12× V1 gene prediction annotations was estimated using SnpEff v.2.0.3 (Cingolani et al., 2012), while the effects of amino acid substitutions on the protein function were predicted in PROVEAN (Choi et al., 2012). Selected polymorphisms were checked by PCR from CB and PX genomic DNA obtained as described above. PN40024 DNA was also analysed as a homozygous positive control. The PCR primers used (Supplementary Table S1, available at JXB online) were designed according to the PN40024 12× reference genome sequence. Primer specificity was checked by BLAST against this genome version in the Genoscope website (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/ GenomeBrowser/Vitis/). PCRs were carried out with approximately 50 ng of genomic DNA using MyTaq™ DNA polymerase (Bioline, Meridian Life Science, Memphis, USA). Amplification products were purified with ExoSAP-IT (USB Products Affymetrix, Cleveland, OH, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and then sequenced by capillary electrophoresis sequencing using the same primers as in PCR. Results Development of parthenocarpic and occasional seeded fruits in CB CB presents a seedless syndrome resulting in fruit and cluster phenotypes clearly different from those observed on its ancestor seeded cultivar PX (Fig. 1A). CB parthenocarpic berries were about six times lighter and smaller than PX berries (Fig. 1B–D). Occasionally, CB developed seeded berries (CB-SDD), which were identified in almost every CB cluster, in 1.6 ± 1.2% of CB berries as an average of all seasons and locations analysed. Generally, CB-SDD berries displayed a comparable size to that of PX, although in 2013 they were significantly smaller (P<0.01) because the PX berries were larger than in other years (Fig. 1B–D). Concerning the number of seeds per berry, almost every CB-SDD berry bore one seed, while PX berries carried 1.7 ± 0.8 seeds in both analysed years (P<0.01, Table 1). The fresh weight of individual seeds was not significantly different between CB-SDD and PX berries, although the mean value was higher in PX (Fig. 1E). Grapevine frequently produces normal-sized hard seeds that are ‘empty’ and unable to germinate (Stout, 1936). Empty seed rate was estimated by floatability as an indication of non-viable seed rate production. This rate was 10-fold higher in CB-SDD (49.5 ± 23.1%) than in PX (4.5 ± 6.6%) seeds. Despite this high rate, a few CB seeds with developed embryos were identified (Supplementary Fig. S1, available at JXB online). These CB seeds did not germinate when sown directly in soil (n=99), whereas ~50% of PX seeds did germinate under these conditions (n=300). Using an in vitro germination protocol, germination of approximately 15% of non-empty CB seeds was obtained allowing their genetic characterization. Pollination of CB flowers with PX pollen did not significantly change either the rate of CB-SDD berries or the number of seeds in these berries. Only six out of 796 berries were seeded in the three CB clusters that were pollinated with PX pollen in 2012 at VALD, while the six seeded berries bore one seed. This result indicated that female defects impeded seed formation in CB and thereby determined its parthenocarpic phenotype. Pollination with exogenous pollen was not required for CB parthenocarpy since seedless fruit setting took place in CB inflorescences that were covered with a paper bag during pollination. Moreover, this experiment carried out at GRAJ in 2013 showed that the proportion of seeded berries was not significantly different between selfpollinated (1.7 ± 1.3%) and free-pollinated (2.0 ± 1.0%) CB clusters. Embryo sac development is absent in CB Ovule development and macrogametogenesis was analysed to search for defects preventing seed formation in CB. As in PX, four normal inverted anatropous ovules were developed in each CB flower, including regular development of nucellus and both outer and inner integuments (Fig. 2A–C). However, while a fully developed embryo sac was identified in most PX ovules (Fig. 2D, G), disorders in CB ovules could be observed Alterations associated with parthenocarpy in grapevine | 263 Fig. 1. Fruit and seed features of PX and CB. (A) Representative clusters in the field at véraison. Arrowheads indicated CB-SDD berries. (B–D) Phenotypic traits measured in ripe grapes: berry fresh weight (B), berry length (C), berry diameter (D), and seed fresh weight (E) in 2011 and 2013. PX, yellow; CB, green. CB berries were classified according to the presence (CB-SDD) or absence (CB-SDL) of seeds. Bars represent means±SD. Different letters (a, b, c) indicate mean values statistically different among the groups at P≤0.01. Table 1. Number of seeds per berry in PX and CB-SDD berries Year 2011 2013 a PX CB-SDD Mean±SD na Mean±SD na 1.66 ± 0.75 1.72 ± 0.84 109 150 1.00 ± 0 1.04 ± 0.23 104 133 Number of berries analysed. before anthesis or after full bloom. In a sample of 30 CB flowers analysed, all but one of the ovules displayed an arrested embryo sac (Fig. 2F–I) and four dying cells were located at the position of the embryo sac in most CB ovules just prior to anthesis (Fig. 2F). According to their linear polar distribution and their short distance, these four degenerating cells could correspond to the macrospores resulting from the reduction division of the megaspore mother cell. Cells in anaphase were also identified at the same sampling time in CB, which further indicates that degeneration takes place after meiosis onset (Fig. 2H). Concurrently, distinctive inner integument cells wrinkled and separated from the outer integument, and degeneration of the nucellus appeared in CB ovules (Fig. 2I). CB is pollen sterile To define whether reproductive defects in CB extended to the male gametophyte, pollen viability was analysed. No viable CB pollen grain was observed in 2012 and 2013, and only 1.4 ± 0.5% viable pollen grains were detected in 2014. In contrast, the PX seeded cultivar showed a pollen viability rate of between 78 and 95% for the three seasons analysed (Fig. 3A, B). Furthermore, pollen germination was negligible in CB, while germination was observed in 43% of PX pollen grains (Fig. 3C, D). Thus, functional pollen grains are hardly ever produced in CB. Fertilization of unreduced gametes triggers seed set and polyploid embryo development in CB To further characterize the phenotype of CB and to elucidate the origin of CB-SDD berries, a set of plants derived from these seeds was obtained. A total of 58 plants were genotyped for nine microsatellite loci to study the segregation of CB alleles. CB and PX shared the same genotype for all nine loci, confirming the previous result by Vargas et al. (2007) (allelic combinations are defined in Supplementary Table S2, available at JXB online). Genotyped CB offspring fell into four different genotype groups: 21 individuals (36%) displayed the same genotype as CB/PX plants (type 1 in Supplementary Table S2); 26 (44.8%) showed the same CB/PX genotype plus additional non-CB/PX alleles in several loci, suggesting that they could be triploid (type 2 in Supplementary Table S2); nine plants (15.5%) showed loss of CB/PX heterozygosity in one or two analysed microsatellite loci as well as additional non-CB/PX alleles in several loci (type 3 in Supplementary Table S2); and finally, two plants (3.4%) showed loss of heterozygosity at three and five loci, respectively, but did not display any non-CB/ PX allele, as could be expected for offspring plants derived from autofertilization of regular haploid gametes (type 4 in Supplementary Table S2). 264 | Royo et al. Fig. 2. Ovule and macrogametophyte development. (A, B) Comparison of ovary transversal sections at 1 dba showing four ovules per pistil in PX (A) and CB (B). (C) Average number of ovules per flower (n=70 per cultivar). (D, E, G, H) Longitudinal sections of ovules in 1 dba ovaries. (D) A mature embryo sac with egg cell (ec), central cell (cc), and synergids (s) developed in PX. (E) A schematic diagram of a normal mature embryo sac within an ovule. (F) CB ovule showing degeneration in the four megaspores after meiosis (md). (G) Number of ovules with a mature embryo sac per flower (n=30). The dot in CB represents an outlier. (H) Detail of a CB ovule with one dividing germline cell at an apparent anaphase (a). (I) Longitudinal section of a CB ovary showing one ovule with nucellus degeneration (nd) and other ovule with megaspores degeneration (md). Bars, 100 µm. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.) Given the possible existence of ploidy changes, the ploidy level was analysed in the CB offspring by flow cytometry. Out of 39 plants analysed, 28 were 3C (probable triploid), nine were 4C (probable tetraploid), and only two were 2C (probable diploid) (Supplementary Fig. S2, available at JXB online, and Supplementary Table S2). The selection of individuals analysed for ploidy level was consciously biased towards individuals that carried non-CB alleles in the microsatellite genotyping, which explains the higher proportion of triploids in comparison with that suggested by the microsatellite genotyping (Supplementary Table S2). Comparison between ploidy level and microsatellite genotypes in 38 individuals analysed with both techniques showed that all type 1 offspring plants with identical microsatellite genotypes as CB/PX were 4C (Table 2), suggesting that they were generated by fertilization of an unreduced CB female gamete by an unreduced CB male gamete. Type 2 and type 3 plants bearing additional non-CB/ PX alleles were confirmed as 3C, indicating the fertilization of an unreduced egg cell by a haploid non-CB sperm cell. Remarkably, the two type 4 plants showing segregation of CB alleles at three and five loci were both 2C like CB, PX, PX selfed-cross offspring plants, and other cultivars analysed as ploidy level controls. Their presence suggested that these two plants could result from a reversion of male and female gamete formation defects. To discard the possibility that polyploid plants might result from the in vitro germination procedure, 68 F1 plants from a self-cross of the Chasselas cultivar germinated in vitro were genotyped for the same nine microsatellites. All 68 plants showed a genotype compatible with the expected segregation for meiotic haploid gametes (data not shown), indicating that polyploidy in CB descendant seedlings is not an artefact of the in vitro germination procedure. Transcriptome alterations during CB flower development In order to characterize the developmental processes altered in CB and to identify candidate mutations responsible for CB parthenocarpy, transcriptomic comparisons were carried out between CB and PX developing flower buds. In 2011, NimbleGen grapevine whole-genome microarrays were used to compare flower buds just prior to anthesis (1 dba), a stage with aborted pollen grains and degenerating macrogametophytes Alterations associated with parthenocarpy in grapevine | 265 Fig. 3. Pollen viability and germination. (A) Alexander staining. Dark pollen is viable, while empty (pale) pollen is sterile. (B) Percentage of pollen viability in three consecutive years. (C) In vitro pollen germination images. (D) Percentage of germination after 24 h of incubation at 25 °C. In (B) and (D), the data are means of three replicates. *, Significant differences between cultivars in the given year (P<0.01; t-test). Bars, 100 µm. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.) Table 2. Ploidy level within CB offspring genotype groups Only individuals analysed by both methods were considered in this table. Genotype and ploidy level from all analysed individuals can be consulted in the Supplementary Table S2. n, Number of individuals analysed. Genotype group n Cytotype (C) frequency 2C Type 1. CB-like Type 2. CB-like + exogenous alleles Type 3. CB segregant + exogenous alleles Type 4. CB selfed segregant 8 22 6 2 3C 4C 100% 100% 100% 100% in CB and mature gametophytes in PX (Figs 2 and 3). In 2012, RNA-seq was used to analyse 10 dba flower buds as the expected stage when microgametogenesis is being completed and macrogametogenesis is initiating (Pratt, 1971; Lebon et al., 2008). Despite the larger library size in one RNAseq PX replicate (Supplementary Table S3, available at JXB online), PCA showed that the first component of variation in both experiments separated the samples by the variant line (component 1 explaining 46 and 69% of variation in RNA-seq and microarray experiments, respectively; Fig. 4A, B). A total of 1958 DEGs (≥2-fold change and Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P≤0.05) between CB and PX were identified (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Table S4, available at JXB online). In both analysed stages, a higher number of CB-downregulated (625 and 969 at 10 and 1 dba, respectively) than CB-upregulated (179 and 430 at 10 and 1 dba, respectively) genes was identified. In spite of developmental, seasonal, and technical divergences, 35% of CB-downregulated genes at 10 dba were also downregulated at 1 dba. In contrast, only 11 genes were CB upregulated in both stages, while 17 DEGs showed inverted expression profiles between both stages. Functional enrichment analysis was performed to understand the biological meaning underlying detected DEGs. Genes that were upregulated in CB flowers at 10 or 1 dba were enriched in dissimilar functional categories (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Table S5, available at JXB online). While CB-upregulated genes at 10 dba were enriched in ‘Sugar transport’, ‘MYB family transcription factor’, and ‘Protein disulfide bond rearrangement’ categories, CB-upregulated genes at 1 dba were mostly enriched in categories related to biotic stress (‘Protein kinase’, ‘Biotic stress response’, ‘Salicylic acid signalling’, and ‘NBS-LRR superfamily’) and oxidative stress (‘Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism’ and ‘Oxidative stress response’). In contrast, enriched categories were more similar between CB-downregulated genes at both studied stages. Indeed, several categories related to vesicular or transmembrane transport (‘Vesicle-mediated trafficking’, ‘Proton transport’, ‘Electron transport’, ‘Phagosome’, and ‘Triose-phosphate transport’) were over-represented among genes that were downregulated in CB at both 10 and 1 dba. Moreover, genes downregulated at each stage were specifically enriched in different cellular (‘Oil body organization and biogenesis’ at 10 dba, and ‘Storage proteins’ and cytoskeleton and cell wall biogenesis-related at 1 dba), metabolic (terpenoid 266 | Royo et al. Fig. 4. (A, B) Transcriptome analysis. PCA of RMA-normalized NimbleGen microarray expression data from 10 dba flower bud samples (A) and TMMnormalized RNA-seq read counts from 1 dba flower bud samples (B). (C) Venn diagram comparing DEGs at 10 and 1 dba. The number of transcripts within each group is indicated. (D, E) Enrichment of functional categories (D) and Corvina expression atlas (Fasoli et al., 2012) organ-specific transcripts (E) in groups of CB versus PX DEGs. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.) and pyruvate metabolism-related at 10 dba and monosaccharide and starch metabolism-related at 1 dba) and regulatory processes (‘PseudoARR-B family transcription factor’ at 10 dba and ‘KIP1 SANTA family transcription factor’, together with two distinct secondary signalling processes at 1 dba). Similarly, ‘Desiccation stress response’ and ‘Drought stress response’ were enriched in 10 and 1 dba downregulated transcripts, respectively. chr8:19689156 chr8:20446425 chr19:3532149 -chr19:3532150 CB specific CB specific CB specific a chr11:4634655 chr13_ random:2434505 chr13:192216 chr16:20771586 chr18:4166072 VIT_13s0067g00270 VIT_16s0098g00350 VIT_18s0001g05110 VIT_11s0016g05300 VIT_13s0019g00350 VIT_05s0020g02350 VIT_06s0061g01340 VIT_19s0014g03380 VIT_08s0007g05750 VIT_08s0007g06780 VIT_02s0025g01660 VIT_05s0020g01400 VIT_07s0104g01290 Gene ID Ribosomal protein 60S SDG29 (SET domain group 29) DNA2-NAM7 helicase Heme oxygenase 1 ARF GTPase activator SAC3/GANP Phosphoglycerate mutase PAP phosphatase Ankyrin Unknown Seven-in-absentia SINA5 SRC2 kinase TUBBY TF Functional annotation C:C T:T G:G C:C A:A G:G C:C AG:AG G:G A:A T:T C:C C:C PN40024 Genotype C:T A:T A:G C:T A:T G:A C:T AG:AG G:G A:A T:T C:C C:C PX C:C T:T G:G C:C A:A G:G C:C AG:CT G:A A:G T:C C:T C:T CB A281T N920I Q443Stop A9T S260R A610T R263C 5′UTR L274S 3′UTR A264V I42V P53P Variant allele effect on protein sequence Deleterious Neutral Deleterious Neutral Deleterious Neutral Deleterious Deleterious Neutral – Neutral Synonym – Variant amino acid effect on protein function –2.56* –0.15 –1468* –1.90 –4.78* 0.20 –3.33* –4.32* 0.88 – –0.11 – – PROVEAN scorea A PROVEAN score for the effect of variant alleles in the protein function of less than or equal to –2.5 was considered ‘deleterious’ and greater than –2.5 was considered ‘neutral’. PX specific PX specific PX specific PX specific PX specific chr5:4050256 chr6:19176704 chr2:1600341 chr5:3126511 chr7:2328801 CB specific CB specific CB specific CB specific PX specific PX specific Variant position(s) Variant type Somatic line specificity for the variant allele in comparison with the PN40024 reference genome, locus affected, locus functional annotation, genotype of each cultivar, and predicted effect of the variant allele in the protein sequence and function are shown. Variant alleles are highlighted in bold. Table 3. RNA-seq polymorphisms distinguishing CB and PX Alterations associated with parthenocarpy in grapevine | 267 268 | Royo et al. To elucidate the floral organs that might be affected by the identified gene expression differences, organ-specific genes and genes expressed in floral organs identified in a whole transcriptome atlas of the Corvina grapevine cultivar (Fasoli et al., 2012) were compared for CB versus PX DEGs (Supplementary Table S4). Enrichment meta-analysis of DEGs in Corvina organ-specific genes identified that genes specifically expressed in sporophytic organs, including vegetative organs, were over-represented among CB-upregulated genes (‘Stamen and petal’ and ‘Stamen’ at 10 dba, ‘Leaf’ and ‘Rachis’ at 1 dba). In contrast, only genes expressed specifically in floral organs, including genes expressed specifically in the microgametophyte (pollen) and genes expressed specifically in carpel (the organ bearing the macrogametophyte, which was not analysed separately in Corvina), were over-represented among CB-downregulated genes (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Table S5). Similar results were obtained when DEGs were meta-analysed for enrichment in genes detected in Corvina floral organs, which showed that CB-upregulated genes were not enriched in genes expressed in floral organs with the exception of petal, while CB-downregulated genes were enriched mainly in pollen-expressed genes (Supplementary Table S5). Sequence polymorphisms between CB and PX, including parthenocarpy-candidate mutations, identified by RNA-seq Polymorphisms between CB and PX were searched for among expressed transcripts resulting from 10 dba flower bud RNAseq alignments. Such polymorphisms might help to discriminate between the CB parthenocarpic variant and PX seeded ancestor, regardless of the fruit phenotype, and furthermore might involve the mutation responsible for the phenotypic variation. A total of 14 polymorphisms were identified between CB and PX. All were heterozygous SNPs in the cultivar carrying the variant allele in comparison with the PN40024 reference genome and were homozygous with the same genotype as the reference genome in the other cultivar (Table 3). Only polymorphisms involving CB-specific variant alleles (in comparison with PX and the reference genome) were considered as potentially responsible for its parthenocarpic phenotype. Seven SNPs involving CB-specific variant alleles were identified, and all were heterozygous SNPs located in exonic regions. The seven SNPs comprised six genes, because two of them were located consecutively on the same gene (Table 3). Capillary electrophoresis sequencing of genomic DNA validated all five CB-specific SNPs tested (Supplementary Fig. S3, available at JXB online). Three CB-specific SNPs involved synonymous changes in the respective predicted proteins, while the other four SNPs involved non-synonymous changes in three genes. Among these, predictive in silico analysis indicated that VIT_19s0014g03380, encoding a HAL2-like 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate (PAP) phosphatase, presented the only non-neutral change, which resulted from two consecutive SNPs causing a leucine-to-serine substitution in the PAP phosphatase-like domain (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. S4A, available at JXB online). Although the mutated leucine was conserved in homologous proteins from other plant species, it was not present in the originally described Saccharomyces cerevisiae HAL2 protein (Supplementary Fig. S4B). This leucine is located in the context of a predicted cyclin recognition site only detected in the grapevine protein (Supplementary Fig. S4B). On the other hand, although genomic deletions have been involved in gamete sterility and grapevine somatic variation (Page et al., 2004; Vezzulli et al., 2012), PX-specific heterozygous SNPs did not concentrate in chromosomal regions (Table 3), and thus they do not support the presence of CB-specific hemizygous regions underlying its variant phenotype. Several grapevine somatic variants resulted from dominant heterozygous cis-acting mutations causing upregulated gene expression (Fernandez et al., 2010, 2013). As hints for these issues, differential allelic frequency between CB and PX in heterozygous positions of CB-upregulated transcripts was also searched for in RNA-seq alignments. No clear evidence of allelic imbalance was identified (data not shown). However, given its homozygosity (confirmed in exonic fragments by capillary electrophoresis sequencing of genomic DNA; data not shown), this phenomenon cannot be ruled out for the putative ERD6 sugar transporterencoding gene VIT_14s0030g00240 (Supplementary Fig. S5, available at JXB online), which was among the most overexpressed genes in both 10 and 1 dba CB flower buds (Supplementary Table S4). In the Corvina expression atlas (Fasoli et al., 2012), VIT_14s0030g00240 was shown to be expressed preferentially in young vegetative tissues, showing its lowest expression in pollen (Supplementary Fig. S5), which may be consistent with ectopic expression in CB flowers. Discussion In order to understand the genetic origin of grapevine parthenocarpy, this study took advantage of recent findings demonstrating that CB is a parthenocarpic somatic variant of the seeded cultivar PX (Vargas et al., 2007). Here, it was shown that the absence of a mature embryo sac is the ultimate cause preventing seed formation in CB. Nevertheless, fruit setting and ripening took place in the absence of fertilization or seed formation, although fruit growth was considerably diminished (Fig. 1). Similarly, a certain amount of small seedless fruits can develop and ripen in grapevine bunches of seeded cultivars, a phenomenon that intensifies when proper pollination is prevented by emasculation or by adverse environmental conditions (Dry et al., 2010; Dauelsberg et al., 2011; Kidman et al., 2014). Indeed, some degree of natural facultative parthenocarpy is extended to other species including the model plant Arabidopsis, whose unfertilized pistils also show partial fruit development with reduced growth (CarbonellBejerano et al., 2010; Sotelo-Silveira et al., 2014). Hence, it is suggested here that CB’s somatic mutation turns the grapevine characteristic facultative parthenocarpy into an obligatory parthenocarpy due to sexual sterility. Alterations associated with parthenocarpy in grapevine | 269 Given the regular development of sporophytic tissues in CB ovules (Fig. 2) and considering the presumable arrest of female meiosis observed at the four-macrospore stage, parthenocarpic CB is more likely to be a meiotic than a gametophytic mutant. Since meiotic defects depend on the diploid sporophyte genotype (Liu and Qu, 2008), a recessive homozygous mutation or, more probably in a somatic variant, a dominant heterozygous mutation, could be the cause for the CB sterile phenotype. The genetic analyses of seeds produced occasionally by CB fruits revealed that CB infrequent functional male and female gametes are mostly unreduced gametes (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2). These gametes should result from apomeiosis (omission of meiotic reduction), considered as the first step of apomixis (Schmidt et al., 2015). However, the absence of diploid seedlings displaying the CB genotype indicated that apomixis did not take place in CB. The ontogeny of diplogametes can be elucidated by analysing the segregation of chromosomes according to microsatellite genotypes (Supplementary Table S2). In tetraploid CB offspring, chromosome duplication might mask losses of heterozygosity produced by meiotic segregation events. In contrast, triploid seedlings, derived from fertilization of CB female diplogametes by non-CB haploid sperm cells, provide an opportunity to study the segregation in CB diplogametes. Segregation of CB alleles was found in 25.7% of the analysed triploids (type 3 in Supplementary Table S2), indicating that the meiotic process was initiated and therefore at least these diplogametes were probably formed by meiotic diplospory, i.e. unreduced megaspores arising from a meiosis modified by nuclear restitution (Koltunow, 1993). By considering in triploid plants those microsatellite loci that are heterozygous in CB and carry a non-CB allele (Supplementary Table S2), a heterozygosity loss rate of 3.2% could be estimated for CB’s female diplogametes. Such a low rate is typically produced by firstdivision nuclear restitution (gametes containing two chromosomes of non-sister chromatids) due to abnormal meiosis I (Bretagnolle and Thompson, 1995). During microgametogenesis of diploid grapevine cultivars, spontaneous formation of unreduced gametes has been estimated at rates between 0 and of 0.37% (Zhang et al., 1998). The level of female unreduced gametes in CB might be above this range considering that, despite that fact that effective fertilization of generally unreduced gametes is required for seed development in CB, 1.6% of setting berries produced one seed, and each berry involved four independent macrogametogenesis events. Consequently, and taking into account the fact that viable unreduced gametes are frequently produced in meiotic mutants (Schmidt et al., 2015), their production by diplospory in CB seems more likely to be a consequence of the CB parthenocarpic syndrome than a grapevine infrequent process unmasked by the sterility of CB plants. When combined with genetic analysis, transcriptomic comparisons have previously been demonstrated to be effective in discovering misexpressed genes harbouring the mutation responsible for the mutant phenotype observed in different grapevine somatic variants (Fernandez et al., 2010, 2013). Unfortunately, CB male and female sterility restricts the possibilities of using genetic analysis in identification of the mutation causing its parthenocarpy, although triploid and diploid generated plants could be useful in the future. As an alternative, this study used RNA-seq to search for candidate mutations by analysing the sequence of expressed transcripts. Moreover, transcriptomic comparisons allowed characterization of the molecular syndrome associated with the somatic variation in CB. Homologues of Arabidopsis microgametophyte development genes were among the most highly downregulated genes in 10 dba CB flowers (Supplementary Table S4). They included the VIT_15s0021g02040 and VIT_17s0000g05490 genes homologous to DUO POLLEN1 and SIDECAR POLLEN, respectively, both required in Arabidopsis for post-meiotic cell division and differentiation of the male germline (Chen and McCormick, 1996; Rotman et al., 2005). Accordingly, CB-downregulated genes were enriched in vesicular trafficking, cell wall biogenesis, cytoskeleton biogenesis, phosphatidylinositol signalling, and G-protein signalling functions (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Table S5); processes that are are involved in cell plate formation and cytokinesis (De Storme and Geelen, 2013; McMichael and Bednarek, 2013). Collectively, downregulation of these genes indicates a lack of post-meiotic mitosis in CB microspores, suggesting that the CB male germline development is also arrested during meiosis. Later, putative pollen maturation and function genes were downregulated at 10 and 1 dba or only at 1 dba, including homologues of AtWRKY2 (VIT_04s0023g00470), AtAGL66 (VIT_07s0031g01140), and AtMYB101 (VIT_12s0059g00700) transcription factors, and RESPIRATORY BURST OXIDASE HOMOLOG J (RBOHJ, VIT_06s0004g03790), CROLIN1 (VIT_14s0066g02480), POLLEN-SPECIFIC LIM PROTEIN 2C (PLIM2C, VIT_15s0046g03370, and VIT_02s0025g03980), AGC KINASE 1.7 (VIT_19s0085g01140), and FERONIAlike receptor kinase ANX1 (VIT_05s0077g00970 and VIT_07s0005g01640). (Supplementary Table S4). All of these are required in Arabidopsis for pollen maturation and/or tube growth differentiation (Adamczyk and Fernandez, 2009; Boisson-Dernier et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Ye and Xu, 2012; Jia et al., 2013; Leydon et al., 2013; Guan et al., 2014; Kaya et al., 2014). Similarly, the observed over-representation of starch metabolism, sugar transport, and proton pumprelated functional categories among CB-downregulated genes resembles gene expression defects in maize pollen sterile lines lacking the post-meiotic pollen starch-filling pathway (Datta et al., 2002). These expression profiles agree with a lack of regular post-meiotic microgametophyte development, which yields sterile pollen grains in CB flowers. In contrast, genes upregulated in 10 dba CB flowers were enriched in stamen-specific genes (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Table S5), which comprised VIT_01s0011g06390, a homologue of the Arabidopsis PHD-type TF MALE STERILITY1 (MS1) required for tapetal pollen wall biosynthesis (Ito et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2007). Expression of MS1 in Arabidopsis is confined to the tapetum, while maximum expression is seen during microspore release and no expression is seen by microspore mitosis I. Highly upregulated genes coding for putative tapetum preferential genes also included homologues 270 | Royo et al. of Arabidopsis sporopollenin biosynthetic enzymes or transporters such as LESS ADHESIVE POLLEN 5 and 6 (VIT_03s0038g01460 and VIT_15s0021g02170), ACYLCOA SYNTHETASE 5 (VIT_01s0010g03720), CYP703A2 (VIT_15s0046g00330), CYP704B1 (VIT_01s0026g02700), MS2 (VIT_08s0007g07100), TETRAKETIDE ALPHAPYRONE REDUCTASE 2 (VIT_01s0011g03480), HYDRO FLAVONOL 4-REDUCTASE-LIKE 1 (VIT_03s0038g04220), and ABCG26 (VIT_19s0015g00960) (Liu and Fan, 2013). In Arabidopsis, most of these genes are regulated downstream of MYB35 and MYB80 (Phan et al., 2011; Liu and Fan, 2013), while homologues of these transcription factors (VIT_17s0000g05400 and VIT_19s0015g01280) along with other MYBs were also CB upregulated in 10 dba flower buds (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). These findings suggest that the exine biosynthetic genetic machinery described in Arabidopsis is conserved in grapevine. Since this machinery generally acts in the tapetum prior to pollen grain post-meiotic mitosis, the overexpression of these genes in 10 dba CB flowers might relate to an arrest of the CB male germline in a pre-mitotic microsporocyte state. Regarding female macrogametophyte development genes, only a few homologues of Arabidopsis genes (Pagnussat et al., 2005; Johnston et al., 2007; Jones-Rhoades et al., 2007; Sanchez-Leon et al., 2012) were detected among DEGs, and were generally downregulated in CB (data not shown). A high number of macrogametophyte-related CB-downregulated genes could be expected given the absence of mature macrogametophytes in CB. The low detection of these genes might be explained by the dilution of macrogametophyte transcripts in the wild-type PX flower given the low proportion of female gametophyte cells in the grapevine flower with only four ovules. Degeneration of the nucellus, dying macrospores, and unviable pollen grains were observed in mature CB flower buds (Figs 2 and 3). Probably connected to these processes, biotic stress, salicylic acid signalling, oxidative stress, and cell death genes were prominently overexpressed in 1 dba CB flowers (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). These genes comprise several EDS1-like defence genes including VvEDS1 (VIT_17s0000g07560) reported as salicylic acid and pathogen responsive in grapevine (Gao et al., 2014). Thus, these CB-upregulated genes are likely to operate in the degeneration of aborted sexual organs. Considering that our results pointed to meiosis abortion as the likely cause of CB’s sterility and impeded seed formation, genes involved in meiosis and/or the cell cycle were screened among the detected DEGs. Few meiosis-specific genes have been reported in plants (Yang et al., 2011; Liu and Qu, 2008). Among them, this study identified that VIT_02s0025g00410 was downregulated in 1 dba CB flowers (Supplementary Table S4), encoding a homologue of the SPO11-2 toposiomerase VIA protein required in Arabidopsis for proper meiotic recombination (Stacey et al., 2006). Such reduced expression might be related to meiosis defects in CB. Nonetheless, the lack of differential expression at 10 dba does not support the presence of a causal mutation involving this gene. Additionally, several putative mitotic cyclins were also downregulated, including a CYCB1;2 (VIT_06s0009g02090), which was the most downregulated gene at 1 dba (Supplementary Table S4). However, genetic variation between CB and PX was not identified by sequencing of this gene plus 1 kb upstream from its predicted start codon (data not shown). Similarly, two putative kinases homologous to AtAurora1 and AtAurora3 were downregulated at 1 dba (VIT_04s0008g00530 and VIT_15s0048g01730, respectively). Reduced activity of these kinases inhibits meiotic chromosome segregation and leads to sexual sterility and the formation of unreduced gametes in Arabidopsis (Demidov et al., 2014), resembling the variant syndrome observed in CB. Nevertheless, read sequences and abundance identified by RNA-seq did not indicate the presence of CB-specific mutations in these genes, suggesting that their misregulation is a consequence of a causal mutation(s) in other loci. RNA-seq sequence data was explored specifically for CB-specific genetic variation that could be responsible for the CB variant phenotype. Seven CB-specific SNPs were identified (Table 3) and considered as parthenocarpy-responsible candidate mutations. Among these, a deleterious effect was predicted for two consecutive CB-specific SNPs producing the substitution of a leucine, with a hydrophobic sidechain, by serine, with a polar side-chain, in the predicted catalytic domain of a putative HAL2-like PAP phosphatase (VIT_19s0014g03380; Supplementary Figs S3 and S4). Considering that the same amino acid substitution produces dominant-negative effects in other proteins (Geller et al., 1998), it is conceivable that this mutation could be involved in the variant phenotype of CB in spite of its heterozygous state. The substituted leucine is integrated in a cyclin recognition site specifically predicted for the grapevine protein (Supplementary Fig. S4B), which might suggest grapevinespecific functions for this gene. Cyclins recognize these motifs and thereby increase the specificity of phosphorylation by cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase complexes. Nevertheless, cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation sites were not detected in the HAL2-like protein. The HAL2-like gene family groups together cation-sensitive phosphatases and AtAHL, the closest Arabidopsis homologue, catalyses the conversion of PAP to AMP, preventing the toxicity of PAP and facilitating the sulphur assimilation pathway. Other family members have been proposed to participate in PAP, phosphoinositol, and abiotic stress signalling (Quintero et al., 1996; Gil-Mascarell et al., 1999; Xiong et al., 2001; Estavillo et al., 2011). Single amino acid substitutions were reported to alter the activity of AtAHL (Cheong et al., 2007), which might support an effect for the mutation identified in VIT_19s0014g03380. Deleterious protein activity of the CB variant allele might alter any of the abovementioned pathways in male and female CB meiocytes, which might in turn impair the meiosis process, resulting in the absence of germline development and, exceptionally, in diplosporic meiosis. Following the grapevine gene expression atlas developed for cultivar Corvina (Fasoli et al., 2012), VIT_19s0014g03380 was preferentially expressed in reproductive organs and showed its maximum expression in pollen (Supplementary Fig. S6, available at JXB online), which might be consistent with a novel sexual reproductionrelated function for the HAL2 gene family. Alterations associated with parthenocarpy in grapevine | 271 Currently, other detected SNPs, unidentified mutations, or epigenetic variation cannot be discarded as possibly being responsible for the CB parthenocarpic phenotype. For example, gene expression and SNP profiles detected in the ERD6 sugar transporter-like gene VIT_14s0030g00240 suggest that it might carry a mutation in regulatory regions causing its ectopic overexpression in CB flowers (Supplementary Fig. S5). Grapevine anthers and ovules are considered highly sensitive organs to sugar deprivation, and particularly at the stage of female meiosis (Lebon et al., 2008). Thus, altered sugar status related to misregulation of this gene might be involved in the CB variant phenotype. Further functional work will be required to confirm these possibilities and demonstrate any connection between candidate genes and the CB phenotype. Conclusions This study represents an integrative approach towards understanding the origin of parthenocarpy in grapevine. The results show that the absence of a mature microgametophyte turns CB into an obligatory parthenocarpic variant. CB is also pollen sterile, while seeds occasionally formed in this variant generally involve polyploid embryos resulting from the fertilization of unreduced gametes produced by meiotic diplospory. Our findings suggest that impaired meiosis is the cellular origin of the altered sexual reproduction and fruit development displayed by CB. Accordingly, transcriptomic analyses revealed a set of grapevine genes likely to be involved in post-meiotic gametophyte division and maturation processes that were downregulated in CB. Transcriptomic hints suggesting that pathogen-like responses operate in the degeneration of aborted sexual organs in CB were also found. Despite the fact that the identification of meiotic mutations causing sterility is generally difficult because of the unfeasibility of genetic analysis, our RNA-seq experiment detected SNP polymorphisms distinguishing CB and PX variant lines and revealed several parthenocarpy-responsible candidate genes. Among these, a putative causal mutation was detected in a HAL2-like gene that has not previously been related to meiosis or sexual reproduction. This study provides a basis for further cytological and molecular assays focusing on cells undergoing meiosis, and shows how genomic approaches can shed light on the origin of grapevine somatic variants including the genetic variation responsible for seedlessness traits. Supplementary data Supplementary data are available at JXB online. Supplementary Fig. S1. Embryos developed within seeds of occasional CB-seeded berries. Supplementary Fig. S2. Representative ploidy profiles obtained by cytometry. Supplementary Fig. S3. Capillary electrophoresis sequencing validation of RNA-seq-identified SNPs. Supplementary Fig. S4. HAL2-like variant protein analysis. Supplementary Fig. S5. ERD6-like VIT_14s0030g00240 candidate gene expression. Supplementary Fig. S6. HAL2-like VIT_19s0014g03380 candidate gene expression. Supplementary Table S1. List of primers used for PCR and sequencing. Supplementary Table S2. Full list of Corinto bianco offspring analysed for microsatellite genotyping and/or ploidy level. Supplementary Table S3. RNA-seq library size and normalization factors. Supplementary Table S4. List of DEGs between CB and PX developing flowers. Supplementary Table S5. Functional and organ enrichment analyses of CB versus PX DEGs. Supplementary File S1. Bash shell and scripts generated to search for sequence polymorphisms. Acknowledgements This study was funded by the Spanish MINECO grant BIO2011-026229. COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) Actions FA1003 and FA1106 supported the exchange of researchers and the presentation of preliminary results. Microarray hybridizations and histological preparations were performed at the Genomics and Histology services of the National Centre for Biotechnology, CNB-CSIC, Madrid, Spain, respectively. RNAseq was carried out at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), Barcelona, Spain. We are grateful to Silvia Hernáiz, Elisabet Vaquero, and José Luis Pérez-Sotés at the ICVV and to the Servicio de Investigación y Desarrollo Tecnológico Agroalimentario (SIDTA) and IMIDRA for technical assistance and/or plant maintenance. References Acanda Y, Prado MJ, González MV, Rey M. 2013. Somatic embryogenesis from stamen filaments in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Mencía): changes in ploidy level and nuclear DNA content. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology—Plant 49, 276–284. Adam-Blondon AF, Lahogue-Esnault F, Bouquet A, Boursiquot JM, This P. 2001. Usefulness of two SCAR markers for marker-assisted selection of seedless grapevine cultivars. Vitis 40, 147–155. Adamczyk BJ, Fernandez DE. 2009. MIKC* MADS domain heterodimers are required for pollen maturation and tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 149, 1713–1723. Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. 2015. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169. Boisson-Dernier A, Roy S, Kritsas K, Grobei MA, Jaciubek M, Schroeder JI, Grossniklaus U. 2009. Disruption of the pollen-expressed FERONIA homologs ANXUR1 and ANXUR2 triggers pollen tube discharge. Development 136, 3279–3288. Bretagnolle F, Thompson JD. 1995. Gametes with the somatic chromosome number: mechanisms of their formation and role in the evolution of autopolyploid plants. New Phytologist 129, 1–22. Carbonell-Bejerano P, Rodriguez V, Royo C, Hernaiz S, MoroGonzalez LC, Torres-Vinals M, Martinez-Zapater JM. 2014. Circadian oscillatory transcriptional programs in grapevine ripening fruits. BMC Plant Biology 14, 78. Carbonell-Bejerano P, Urbez C, Carbonell J, Granell A, PerezAmador MA. 2010. A fertilization-independent developmental program triggers partial fruit development and senescence processes in pistils of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 154, 163–172. Carrera E, Ruiz-Rivero O, Peres LE, Atares A, Garcia-Martinez JL. 2012. Characterization of the procera tomato mutant shows novel functions of the SlDELLA protein in the control of flower morphology, cell division and expansion, and the auxin-signaling pathway during fruit-set and development. Plant Physiology 160, 1581–1596. Chasan R, Walbot V. 1993. Mechanisms of plant reproduction: questions and approaches. The Plant Cell 5, 1139–1146. 272 | Royo et al. Chen YC, McCormick S. 1996. sidecar pollen, an Arabidopsis thaliana male gametophytic mutant with aberrant cell divisions during pollen development. Development 122, 3243–3253. Cheong JJ, Hwang I, Rhee S, Moon TW, Choi YD, Kwon HB. 2007. Complementation of an E. coli cysteine auxotrophic mutant for the structural modification study of 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase. Biotechnology Letters 29, 913–918. Chevalier F, Iglesias SM, Sánchez ÓJ, Montoliu L, Cubas P. 2014. Plastic embedding of Arabidopsis stem sections. Bio-protocol 4, e1261. Choi YA, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. 2012. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS One 7, e46688. Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen TM, Wang L, Land SJ, Ruden DM, Liu X. 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain W1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6, 80–92. Cresti M, Ciampolini F. 1999. Ultrastructural characteristics of pollen development in Vitis vinifera L. (cv. Sangiovese). Vitis 38, 141–144. Datta R, Chamusco KC, Chourey PS. 2002. Starch biosynthesis during pollen maturation is associated with altered patterns of gene expression in maize. Plant Physiology 130, 1645–1656. Dauelsberg P, Matus JT, Poupin MJ, Leiva-Ampuero A, Godoy F, Vega A, Arce-Johnson P. 2011. Effect of pollination and fertilization on the expression of genes related to floral transition, hormone synthesis and berry development in grapevine. Journal of Plant Physiology 168, 1667–1674. De Storme N, Geelen D. 2013. Cytokinesis in plant male meiosis. Plant Signaling & Behavior 8, e23394. Demidov D, Lermontova I, Weiss O, et al. 2014. Altered expression of Aurora kinases in Arabidopsis results in aneu- and polyploidization. The Plant Journal 80, 449–461. Dorcey E, Urbez C, Blazquez MA, Carbonell J, Perez-Amador MA. 2009. Fertilization-dependent auxin response in ovules triggers fruit development through the modulation of gibberellin metabolism in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 58, 318–332. Dry PR, Longbottom ML, McLoughlin S, Johnson TE, Collins C. 2010. Classification of reproductive performance of ten winegrape varieties. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 16, 47–55. Estavillo GM, Crisp PA, Pornsiriwong W, et al. 2011. Evidence for a SAL1-PAP chloroplast retrograde pathway that functions in drought and high light signaling in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 23, 3992–4012. Fasoli M, Dal Santo S, Zenoni S, et al. 2012. The grapevine expression atlas reveals a deep transcriptome shift driving the entire plant into a maturation program. The Plant Cell 24, 3489–3505. Fernandez L, Chaib J, Martinez-Zapater JM, Thomas MR, Torregrosa L. 2013. Mis-expression of a PISTILLATA-like MADS box gene prevents fruit development in grapevine. The Plant Journal 73, 918–928. Fernandez L, Torregrosa L, Segura V, Bouquet A, Martinez-Zapater JM. 2010. Transposon-induced gene activation as a mechanism generating cluster shape somatic variation in grapevine. The Plant Journal 61, 545–557. Gao F, Dai R, Pike SM, Qiu W, Gassmann W. 2014. Functions of EDS1like and PAD4 genes in grapevine defenses against powdery mildew. Plant Molecular Biology 86, 381–393. Geller DS, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Vallo Boado A, Schifter S, Bayer M, Chang SS, Lifton RP. 1998. Mutations in the mineralocorticoid receptor gene cause autosomal dominant pseudohypoaldosteronism type I. Nature Genetics 19, 279–281. Gil-Mascarell R, Lopez-Coronado JM, Belles JM, Serrano R, Rodriguez PL. 1999. The Arabidopsis HAL2-like gene family includes a novel sodium-sensitive phosphatase. The Plant Journal 17, 373–383. Grimplet J, Van Hemert J, Carbonell-Bejerano P, Diaz-Riquelme J, Dickerson J, Fennell A, Pezzotti M, Martinez-Zapater JM. 2012. Comparative analysis of grapevine whole-genome gene predictions, functional annotation, categorization and integration of the predicted gene sequences. BMC Research Notes 5, 213. Guan Y, Meng X, Khanna R, LaMontagne E, Liu Y, Zhang S. 2014. Phosphorylation of a WRKY transcription factor by MAPKs is required for pollen development and function in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genetics 10, e1004384. Ibáñez J, Vélez MD, de Andrés MT, Borrego J. 2009. Molecular markers for establishing distinctness in vegetatively propagated crops: a case study in grapevine. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 119, 1213–1222. Ito T, Nagata N, Yoshiba Y, Ohme-Takagi M, Ma H, Shinozaki K. 2007. Arabidopsis MALE STERILITY1 encodes a PHD-type transcription factor and regulates pollen and tapetum development. Plant Cell 19, 3549–3562. Jia H, Li J, Zhu J, Fan T, Qian D, Zhou Y, Wang J, Ren H, Xiang Y, An L. 2013. Arabidopsis CROLIN1, a novel plant actin-binding protein, functions in cross-linking and stabilizing actin filaments. Journal of Biological Chemistry 288, 32277–32288. Johnston AJ, Meier P, Gheyselinck J, Wuest SE, Federer M, Schlagenhauf E, Becker JD, Grossniklaus U. 2007. Genetic subtraction profiling identifies genes essential for Arabidopsis reproduction and reveals interaction between the female gametophyte and the maternal sporophyte. Genome Biology 8, R204. Jones-Rhoades MW, Borevitz JO, Preuss D. 2007. Genome-wide expression profiling of the Arabidopsis female gametophyte identifies families of small, secreted proteins. PLoS Genetics 3, 1848–1861. Kaya H, Nakajima R, Iwano M, et al. 2014. Ca2+-activated reactive oxygen species production by Arabidopsis RbohH and RbohJ is essential for proper pollen tube tip growth. The Plant Cell 26, 1069–1080. Kidman CM, Mantilla SO, Dry PR, McCarthy MG, Collins C. 2014. Effect of water stress on the reproductive performance of Shiraz (Vitis vinifera L.) grafted to rootstocks. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 65, 96–108. Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. 2013. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biology 14, R36. Koltunow AM. 1993. Apomixis: embryo sacs and embryos formed without meiosis or fertilization in ovules. The Plant Cell 5, 1425–1437. Laucou V, Lacombe T, Dechesne F, et al. 2011. High throughput analysis of grape genetic diversity as a tool for germplasm collection management. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 122, 1233–1245. Lebon G, Wojnarowiez G, Holzapfel B, Fontaine F, Vaillant-Gaveau N, Clement C. 2008. Sugars and flowering in the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 2565–2578. Leydon AR, Beale KM, Woroniecka K, Castner E, Chen J, Horgan C, Palanivelu R, Johnson MA. 2013. Three MYB transcription factors control pollen tube differentiation required for sperm release. Current Biology 23, 1209–1214. Li H, Hansdsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. Liu J, Qu LJ. 2008. Meiotic and mitotic cell cycle mutants involved in gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant 1, 564–574. Liu L, Fan XD. 2013. Tapetum: regulation and role in sporopollenin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Molecular Biology 83, 165–175. Loureiro J, Rodriguez E, Dolezel J, Santos C. 2007. Two new nuclear isolation buffers for plant DNA flow cytometry: a test with 37 species. Annals of Botany 100, 875–888. McMichael CM, Bednarek SY. 2013. Cytoskeletal and membrane dynamics during higher plant cytokinesis. The New Phytologist 197, 1039–1057. Medina I, Carbonell J, Pulido L, et al. 2010. Babelomics: an integrative platform for the analysis of transcriptomics, proteomics and genomic data with advanced functional profiling. Nucleic Acids Research 38, W210–W213. Murashige T, Skoog F. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 15, 473–497. Page DR, Kohler C, Da Costa-Nunes JA, Baroux C, Moore JM, Grossniklaus U. 2004. Intrachromosomal excision of a hybrid Ds element induces large genomic deletions in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 101, 2969–2974. Pagnussat GC, Yu HJ, Ngo QA, Rajani S, Mayalagu S, Johnson CS, Capron A, Xie LF, Ye D, Sundaresan V. 2005. Genetic and molecular identification of genes required for female gametophyte development and function in Arabidopsis. Development 132, 603–614. Alterations associated with parthenocarpy in grapevine | 273 Pelsy F. 2010. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of diversity within grapevine varieties. Heredity (Edinburgh) 104, 331–340. Peterson R, Slovin JP, Chen C. 2010. A simplified method for differential staining of aborted and non-aborted pollen grains. International Journal of Plant Biology 1, 13. Phan HA, Iacuone S, Li SF, Parish RW. 2011. The MYB80 transcription factor is required for pollen development and the regulation of tapetal programmed cell death in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 23, 2209–2224. Pratt C. 1971. Reproductive anatomy in cultivated grapes—a review. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 22, 92–109. Quintero FJ, Garciadeblas B, Rodriguez-Navarro A. 1996. The SAL1 gene of Arabidopsis, encoding an enzyme with 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase and inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase activities, increases salt tolerance in yeast. The Plant Cell 8, 529–537. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. Robinson MD, Oshlack A. 2010. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biology 11, R25. Rotman N, Durbarry A, Wardle A, Yang WC, Chaboud A, Faure JE, Berger F, Twell D. 2005. A novel class of MYB factors controls sperm-cell formation in plants. Current Biology 15, 244–248. Ruzin SE. 1999. Plant microtechnique and microscopy . New York: Oxford University Press, 322. Sanchez-Leon N, Arteaga-Vazquez M, Alvarez-Mejia C, et al. 2012. Transcriptional analysis of the Arabidopsis ovule by massively parallel signature sequencing. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 3829–3842. Schmidt A, Schmid MW, Grossniklaus U. 2015. Plant germline formation: common concepts and developmental flexibility in sexual and asexual reproduction. Development 142, 229–241. Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9, 671–675. Sotelo-Silveira M, Marsch-Martinez N, de Folter S. 2014. Unraveling the signal scenario of fruit set. Planta 239, 1147–1158. Stacey NJ, Kuromori T, Azumi Y, Roberts G, Breuer C, Wada T, Maxwell A, Roberts K, Sugimoto-Shirasu K. 2006. Arabidopsis SPO11-2 functions with SPO11-1 in meiotic recombination. The Plant Journal 48, 206–216. Stout AB. 1936. Seedlessness in Grapes. New York State Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin , Vol. 238. Geneva, NY: New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, 68. Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. 2012. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Briefings in Bioinformatics 14, 178–192. Torregrosa L, Fernandez L, Bouquet A, Boursiquot JM, Pelsy F, Martínez-Zapater JM. 2011. Origins and consequences of somatic variation in grapevine. In: Adam-Blondon A-F, Martinez-Zapater J-M, Kole C, eds. Genetics, genomics, and breeding of grapes. Jersey , British Isles: Science Publishers, 68–92. Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, Pachter L. 2013. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nature Biotechnology 31, 46–53. Vargas AM, Vélez MD, de Andrés MT, Laucou V, Lacombe T, Boursiquot J-M, Borrego J, Ibáñez J. 2007. Corinto bianco: a seedless mutant of Pedro Ximenes. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 58, 540–543. Varoquaux F, Blanvillain R, Delseny M, Gallois P. 2000. Less is better: new approaches for seedless fruit production. Trends in Biotechnology 18, 233–242. Vezzulli S, Leonardelli L, Malossini U, Stefanini M, Velasco R, Moser C. 2012. Pinot blanc and Pinot gris arose as independent somatic mutations of Pinot noir. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 6359–6369. Weaver RJ. 1960. Grape growing in Greece. Economic Botany 14, 207–224. Xiong L, Lee B, Ishitani M, Lee H, Zhang C, Zhu JK. 2001. FIERY1 encoding an inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase is a negative regulator of abscisic acid and stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Genes & Development 15, 1971–1984. Yang C, Vizcay-Barrena G, Conner K, Wilson ZA. 2007. MALE STERILITY1 is required for tapetal development and pollen wall biosynthesis. Plant Cell 19, 3530–3548. Yang H, Lu P, Wang Y, Ma H. 2011. The transcriptome landscape of Arabidopsis male meiocytes from high-throughput sequencing: the complexity and evolution of the meiotic process. The Plant Journal 65, 503–516. Yao J, Dong Y, Morris BA. 2001. Parthenocarpic apple fruit production conferred by transposon insertion mutations in a MADS-box transcription factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 98, 1306–1311. Ye J, Xu M. 2012. Actin bundler PLIM2s are involved in the regulation of pollen development and tube growth in Arabidopsis. Journal of Plant Physiology 169, 516–522. Zhang XZ, Liu GJ, Zhang DM. 1998. Occurrence and cytogenetic development of unreduced pollen in Vitis. Vitis 37, 63–65. Zhang Y, He J, McCormick S. 2009. Two Arabidopsis AGC kinases are critical for the polarized growth of pollen tubes. The Plant Journal 58, 474–484.