* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Pavement cell chloroplast behaviour and interactions with other

Cell membrane wikipedia , lookup

Green fluorescent protein wikipedia , lookup

Tissue engineering wikipedia , lookup

Extracellular matrix wikipedia , lookup

Endomembrane system wikipedia , lookup

Cell encapsulation wikipedia , lookup

Programmed cell death wikipedia , lookup

Cell growth wikipedia , lookup

Cellular differentiation wikipedia , lookup

Cell culture wikipedia , lookup

Cytokinesis wikipedia , lookup

Organ-on-a-chip wikipedia , lookup

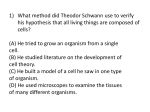

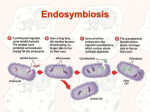

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd. Pavement cell chloroplast behaviour and interactions with other organelles in Arabidopsis thaliana Kiah A. Barton, Michael R. Wozny, Neeta Mathur, Erica-Ashley Jaipargas, Jaideep Mathur 1* 1. Laboratory of Plant Development and Interactions, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of Guelph, 50 Stone Rd., Guelph. ON. N1G2W1. Canada. * Author for correspondence *JM [email protected] Tel:1 (519) 824 4120 ext. 56636: Fax: 1 KB [email protected] MW [email protected] NM [email protected] EJ [email protected] Short description: The spatiotemporal relationship between pavement cell chloroplasts and their surroundings in Arabidopsis thaliana is presented. JCS Advance Online Article. Posted on 20 March 2017 Journal of Cell Science • Advance article (519) 837-1802 Abstract Chloroplasts are a characteristic feature of green plants. Mesophyll cells possess the majority of chloroplasts and it is widely believed that with the exception of guard cells, the epidermal layer in most higher plants does not contain chloroplasts. However, recent observations on Arabidopsis have shown a population of chloroplasts in pavement cells that are smaller than mesophyll chloroplasts and have a high stroma to grana ratio. Here using stable transgenic lines expressing fluorescent proteins targeted to the plastid stroma, plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, tonoplast, nucleus, mitochondria, peroxisomes, F-actin and microtubules we characterize the spatiotemporal relationships between the pavement cell chloroplasts (PCC) and their subcellular environment. Observations on the PCC suggest a source-sink relationship between the epidermal and the mesophyll layers and the Arabidopsis mutants glabra2 (gl2) and immutans (im) underscore their developmental plasticity. Our findings lay down the foundation for further investigations aimed at understanding the precise role and contributions of Journal of Cell Science • Advance article PCC in plant interactions with the environment. Introduction Plastids are multi-functional, pleomorphic organelles of purported endo-symbiotic origin that display a characteristic double membrane envelope in plants and green algae (Wise, 2007). Observations on the basic features of plastids date back to the mid-seventeenth century (reviewed by Gunning et al., 2007). All plastid types are believed to originate as colourless pro-plastids in meristems (Schimper, 1883, 1885) and their subsequent differentiation takes place according to tissue and developmental requirements (Jarvis and López-Juez, 2013; Paila et al., 2015; Liebers et al., 2017). Early studies by Schimper (1883, 1885) established the inter-convertibility of plastids from one type to another. Presently, on the basis of pigmentation, chloroplasts are distinguished from other plastids by the presence of chlorophyll, chromoplasts by the predominance of other pigments, and leucoplasts by the absence of all pigmentation. In higher plants, the majority of chloroplasts are found in the leaf mesophyll tissue and at the ultra-structural level display the classical thylakoid membrane system of stacked thylakoid grana connected by intergranal lamellae. However, chloroplasts in the bundle sheath cells of C4 plants are often agranal (Bisalputra et al., 1969; Woo et al., 1970), suggesting that welldefined grana are not a requirement for identification as a chloroplast. Though the majority of photosynthesis occurs in the mesophyll, the guard cells of most plant species are recognized as having chloroplasts that possess an active electron transport chain, are capable of fixing carbon dioxide and play an 2014). In addition to guard cells the aerial epidermis consists of trichomes and large pavement cells. It is widely believed that chloroplasts are absent from the pavement cells of Arabidopsis and most other higher plants (Brunkard et al., 2015; MacDonald, 2003; Smith, 2005; Bowes and Mauseth, 2008; Solomon et al., 2010; Vaughan, 2013). However, the presence of chloroplasts in pavement cells of Arabidopsis thaliana is well documented (Pyke and Leech, 1994; Roberston et al., 1996; Vitha et al., 2001; Joo et al., 2005; Pyke, 2009) and was reinforced by recent observations (Barton et al., 2016). Journal of Cell Science • Advance article important role in stomatal opening and closing (Lawson, 2008; Lawson et al., Pavement cell chloroplasts (PCC) in Arabidopsis are comparable in size to guard cell chloroplasts but are approximately half the size of mesophyll chloroplasts (MCC). In the jigsaw shaped pavement cells in expanded cotyledons and leaves of Arabidopsis, 9 to 15 PCC are found per cell, while a single mesophyll cell may contain over 120 chloroplasts (Pyke and Leech, 1992, 1994; Barton et al., 2016). PCC are photosynthetically active and show clear grana, but their chlorophyll autofluorescence signal is low compared to MCC (Barton et al., 2016). A high stroma to thylakoid ratio in PCC makes them easier to image than MCC using plastid-targeted fluorescent proteins, so these plastids are sometimes used for visual studies of plastid responses (Kwok and Hanson, 2004a; Higa et al., 2014; Caplan et al., 2015; Brunkard et al., 2015). However, whether this small population shows responses that are representative of all chloroplasts is uncertain and much remains unknown about the spatiotemporal behaviour of PCC or their relationship with other cellular components and compartments. Here, using a range of fluorescent protein probes targeted to the chloroplasts and other subcellular structures, we have investigated PCC and their surroundings in Arabidopsis thaliana and contrasted PCC response to light and sucrose with that of MCC. The creation of new transgenic plant resources, and characterization of PCC from a cell biological, physiological and developmental perspective lays down the foundation for further investigations on the actual contribution of these small chloroplasts during Journal of Cell Science • Advance article plant interactions with the environment. Results Identifying the PCC and creating resources for their characterization The presence of PCC in Arabidopsis was best appreciated when the pavement cells were viewed from a lateral perspective. As shown in Fig. 1 this view was easily achieved for pavement cells lying at the edges of cotyledons and leaves. It allowed direct observation of the subcellular environment around the PCC without interference from the fluorescence signal of underlying mesophyll layers. The PCC are small when compared to the MCC, however even from a lateral view, it can appear that some small chloroplasts are in the mesophyll plane when the pavement and mesophyll cells are closely interlocked. In order to confirm that the smaller chloroplasts were located exclusively in the pavement cells, the Arabidopsis crooked (crk) and wurm (wrm) mutants were used. In these mutants, epidermal cells in the hypocotyl, cotyledons, and young leaves become abnormally elongated upon detachment from each other along the long axis (Fig. 1A; Mathur, 2005). Similar to wild type plants two chloroplast populations were visible in crk and wrm, one consisting of small chloroplasts and the other of large chloroplasts. The pavement cells that had curved out of the general epidermal plane in crk and wrm plants exhibited small PCC clearly, while cells in the layers beneath displayed only the larger MCC. (Fig. 1B; Movie S1). In wild type Arabidopsis uncertainty about the exact location of chloroplasts in the epidermal or the mesophyll layer can thus be resolved by observing their relative sizes. A number of double transgenic and mutant Arabidopsis lines different targeted fluorescent probes were created for understanding PCC behaviour in relation to their subcellular environment (Table 1). The following general observations were made on the interactions between the highlighted organelles and the PCC. Pavement cell chloroplasts and their surroundings In 10 day-old cotyledons of soil grown tpFNR:GFP-RFP:ER plants, the average cell depth for guard cells was estimated at 12.4 ± 0.6 μm, for pavement cells at 38.3 ± 3.0 μm and for mesophyll cells at 53.8 ± 4.6 μm. In comparison the pavement cells in petioles of the first leaves and cotyledons were relatively elongated and thin with depths ranging from 12-17 µm. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article expressing Observations in many plants taken at different times of the day on PCC established that they were not always located in the same position with regard to the upper cell boundary. While observations taken after an eight-hour dark period showed up to 90% of the PCC located near the upper surface (Fig. 1C), they were localized mainly near the lower surface of the cell if the plants had been exposed for a few hours to light intensity of about 120 µmol m-2s-1. Due to their localization near the lower surface of the pavement cell these chloroplasts appeared to lie on top of the MCC layer (Fig.1D). In both locations the PCC extended and retracted stromules sporadically. These observations on the relative sizes and positions of PCC and MCC were reinforced using a line expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP) targeted to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A). Similar to the situation for the majority of organelles in plant cells (Reviewed by Vick and Nebenführ, 2012; Geitmann and Nebenführ, 2015) and in agreement with Kwok and Hanson (2004a), time-lapse imaging of the double transgenic tpFNR:mEosFP-GFP:mTalin line showed PCC alignment and movement along F-actin strands (Fig. 2B,C; Movie S2) and the F-actin could be traced as a loose cage around the PCC (Fig. 2B). Compared to the dynamic association between PCC and F-actin their spatiotemporal relationship with microtubules, investigated using a tpFNR:mEosFP- GFP:MAP4 line, was less clear. While a collapsed Z- stack of confocal images conveyed the impression that the PCC were embedded between cortical microtubules (Fig. 2D), in most optical sections the PCC were found in a relationship with microtubules as stromules were often extended parallel to the cortical microtubule array, but could also extend perpendicular to it (Fig. 2E). In the instances that alignment with neighbouring cortical microtubules (Fig. 2E) was observed it was not sustained and did not occur along a particular microtubule. Often a stromule extended across multiple microtubules and while retracting could pause at several locations. In contrast to the microtubules, time-lapse observations in the tpFNR:mEosFP-GFP:Vac line highlighted the tonoplast and revealed the PCC were almost surrounded by, and could be tugged on by the movement of thin vacuolar membrane tubules (Fig. 2F). For PCC located on the cell periphery Journal of Cell Science • Advance article distinct plane. PCC with extended stromules did not show a consistent (Fig. 2G), the vacuole was closely appressed to the plastid on the side interior to the cell. In all cases, time-lapse imaging suggested that the vacuolar membrane flowed loosely over the chloroplast surface (Fig. 2H; Movie S3). Whereas a top down view (Fig. 2H) also suggested a very close association between PCC and the vacuolar membranes, we were perplexed by the presence of many areas that looked very similar in size to the PCC but did not show the typical chloroplast fluorescence (Fig. 2I). We found the observations with the vacuole probe reminiscent of earlier observations on chloroplasts made using lines co-expressing tpFNR:GFP and an ER-targeted RFP (Schattat et al., 2011). As reported earlier (Schattat et al., 2011) the PCC were embedded within an ER cage surrounding the entire chloroplast (Fig. 2K) and both organelles moved in concert. Stromules extended sporadically from the PCC and aligned closely with the ER mesh or extended along ERlined channels (Fig. 2L-arrowheads,M). In order to understand the PCCvacuole-ER relationship better we developed a double transgenic line coexpressing the vacuole targeted GFP and the ER targeted RFP. Using this line it was found that the vacuole presses against and outlines other organelles in a similar manner. Lateral views of PCC in the GFP:Vac-RFP:ER line showed that the ER-cage was located between the vacuolar membrane and the PCC (Fig. 2J) and that ER bodies could be amongst the organelles appearing similar in size to PCC (Fig. 2J). The vacuolar tubules also engulfed the nucleus and allowed us to observe nucleus associated PCC (Fig. 2N). A line co-expressing the 15 ± 3 % (N=80 cells from 4 seedlings) of cotyledon pavement cells in 7 day old seedlings, anywhere between 3 to 12 PCC could be found in the perinuclear region (Fig. 2O). The nuclear association was often transient and a variable number of PCC were observed reaching the perinuclear region or moving away from it. In the remaining cells, the PCC were dispersed and showed no clear nuclear association. Upon observing stromules extended by the perinuclear PCC we were unable to find a clear indication whether the stromules extended towards or away from the nucleus. Each probe described here requires a more detailed assessment for understanding the details of PCC response to different environmental stimuli. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article tpFNR:GFP and a nucleus-targeted RFP was developed and showed that in However, the PCC are clearly present in a narrow cytoplasmic sleeve appressed to the pavement cell boundary, comprising of the plasma membrane and the subtending cytoskeleton, by the dynamic vacuole. The narrow cytoplasmic sleeve with PCC is also populated by small organelles like mitochondria and peroxisomes and PCC relation with these organelles was investigated next. Assessing PCC interactivity with mitochondria and peroxisomes Published biochemical (reviewed by Raghavendra and Padmasree, 2003; Hodges et al., 2016) as well as microscopy-based findings (Frederick and Newcomb, 1969; Sage and Sage, 2009; Gao et al., 2016; Jaipargas et al., 2016) suggest close interactivity between chloroplasts, peroxisomes and mitochondria. Stromules extended from plastids have been specifically implicated in such interactions (Kwok and Hanson, 2004a) and a relation between stromule extension and the cell size has been proposed (Waters et al., 2004). Between 9 and 15 small chloroplasts are found in a pavement cell compared to up to 120 chloroplasts of nearly twice their size in mesophyll cells (Pyke and Leech, 1992, 1994), thus the pavement cells provide a much larger total cell volume to total chloroplast volume ratio as compared to the mesophyll cell. Based on published literature (Waters et al., 2004) there seemed to be a high likelihood of observing stromules and their interactions with small organelles in these cells. We created a double transgenic line tpFNR:YFP-mitoGFP (Logan and Leaver, 2000) to investigate the interactivity line (Fig. 3B) for observing PCC interactions with peroxisomes. Both mitochondria and peroxisomes appear to come into close proximity with the PCC. Time-lapse image series showed that associations with PCC could range from fleeting single-frame encounters to sustained encounters of over 10 seconds. However, small organelles that were permanently associated with PCC were not observed. Mitochondria and peroxisomes can both show punctate or elongated morphologies. Elongated organelles were very dynamic and the region in contact with the plastid could change over time. Fig. 3C summarizes the variations in organelle shape and position that were seen. In order to determine if these organelles associated Journal of Cell Science • Advance article between mitochondria and PCC (Fig. 3A) and a tpFNR:mEosFP-GFP-PTS1 more frequently with stromules or with the plastid body, the total number of mitochondria or peroxisomes that came into close apposition with PCC producing stromules over time was counted and averaged. The average number of mitochondria or peroxisomes in close juxtaposition to the PCC main body or to the extended stromule did not differ (Fig. 3D). In the PCC considered in these time-lapse image sets, the average perimeter that was available for association with other organelles did not differ between the plastid bodies and the stromules (Fig. S1). Having observed the general subcellular environs of the PCC we focused next on the implications of their position relative to the MCC. PCC positioning over the MCC creates a physiological relationship between the two layers PCC have photosynthetic capability, however the number and thickness of grana and the chlorophyll content in PCC is low compared to MCC (Barton et al., 2016). In Arabidopsis the general stromule formation frequency of PCC is known to increase during the day (Schattat et al., 2012a; Brunkard et al., 2015) but whether this is representative of the response of MCC has yet to be studied. Observations taken separately on the two cell layers in 6 week old short day grown plants showed that the stromule frequency of PCC increased in response to light exposure and continued to rise through the 8 hour light cycle. By contrast the MCC had a consistently low stromule formation frequency that showed no apparent change throughout the Exogenous sugar feeding is known to increase stromule formation frequency (Schattat and Klösgen, 2011), and was used to determine if PCC and MCC stromule formation responses differed under other conditions. Intact 21 day old Arabidopsis plants that were floated in 40mM sucrose in the dark showed an increase in stromule frequency of both PCC and MCC (Fig. 4B). Control treatments indicated that neither the immersion in water nor the prolonged darkness influenced the basal stromule levels. PCC stromule frequency was consistently higher than that of MCC, but for both populations the increase began within the first hour, and continued to rise throughout the 5 hours of treatment (Fig. 4B). However, the stromule formation response from Journal of Cell Science • Advance article day (Fig. 4A). MCC was almost entirely inhibited when the plants were exposed to light during the sucrose treatment, while the PCC response was unchanged from the dark treatment (Fig. 4C, D). During our light and sugar experiments, chlorophyll autofluorescence confirmed that the plastids of all pavement cells observed were indeed chloroplasts. However, reports of leucoplasts in pavement cells of Arabidopsis do exist, so we further investigated under what conditions this could occur and how the behaviour and appearance of epidermal leucoplasts differ from PCC. A developmental perspective: Exploring PCC and plastid- interconvertibility Leucoplasts, by definition (Schimper, 1883; 1885), do not contain chlorophyll and are stroma-rich. When using the stroma-targeted tpFNR-GFP probe (Marques et al., 2004; Schattat et al., 2011), leucoplasts appeared uniformly green fluorescent (emission 510-520 nm), while in chloroplasts the green stromal fluorescence surrounded the chlorophyll autofluorescence of the grana (emission 650-750nm). This allowed us to monitor the presence of both plastid types in pavement cells during development. We first investigated whether chloroplasts are the default plastid type in the epidermis of Arabidopsis. Observations on Arabidopsis leaves in the tpFNR:GFP line revealed that unlike in the chloroplast-containing guard and pavement cells, trichome plastids are leucoplasts (Fig 5A). As trichomes are initiated from protodermal 2005), if the chloroplast represents the standard plastid type in epidermal cells, the chlorophyll must be lost from trichome plastids as the cell differentiates. In the glabra2 (gl2) mutant of Arabidopsis the trichome differentiation is initiated, but the majority of trichomes do not remain committed to the trichome fate and either mature into small spikes (Fig. 5B,C) or collapse into large misshapen cells very similar to pavement cells (Fig. 5D; Rerie et al., 1994). In a gl2 GFP:mTalin line where the green fluorescence provides cellular context to the chlorophyll auto-fluorescence, the aberrant trichomes exhibit chloroplasts rather than leucoplasts (Fig 5E,F). Therefore, Journal of Cell Science • Advance article cells in expanding leaves (Szymanski et al., 2000; Schellmann and Hülskamp, guard cells, pavement cells and trichome cells that have not completely differentiated all contain chloroplasts in Arabidopsis. We next looked for conditions under which epidermal leucoplasts might be observed. Leucoplasts were not seen in cotyledon pavement cells of healthy 7 to 12 day old tpFNR:GFP plants grown either in the soil or on agarsolidified medium, nor were they seen in green leaves of older plants. Pavement cell leucoplasts were only found in regions of these plants with mechanical damage or in plants that showed high anthocyanin accumulation indicative of stress. Chloroplasts remained the predominant population in older cotyledons between 14 and 28 days. Seldom, uniformly green fluorescent leucoplasts and senescing chloroplasts with a distinct separation of GFP and chlorophyll fluorescence but an intact boundary could be seen (Fig. 6A). In chlorotic tissue of 6 week old plants, the chlorophyll signal was minimal, but still present in most epidermal plastids. Similar to senescing cotyledons, leucoplasts could be seen (Fig. 6B), but were extremely infrequent. It is therefore possible to see pavement cell leucoplasts under some conditions, but the occurrence is rare. Since we were unable to consistently observe leucoplasts in pavement cells in young wild type tissue, we used the immutans (im) mutant of Arabidopsis (Rédei, 1967; Wetzel et al., 1994) for a thorough comparison of PCC and leucoplast appearance and behaviour. The im mutant is variegated with bright green chloroplast-containing regions randomly interspersed with white sectors that contain leucoplasts as 1994). This mutant thus provided an ideal tool to investigate the different appearances of leucoplasts and chloroplasts within the same tissue. Introduction of the tpFNR:GFP probe into im allowed easy identification of leucoplasts by their complete lack of chlorophyll autofluorescence (Fig. 6E). The shape of the various plastid types was clearly different, with leucoplasts displaying an elongate and irregular form as compared to the consistent, round to oval shape of chloroplasts (e.g. Fig. 1C). PCC in green sectors, apart from the occasional extension of stromules, maintained their lens-like shape over time, whereas leucoplasts exhibited a dynamic morphology. In rare cases, individual leucoplasts did maintain a round morphology over time. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article well as intermediate plastid forms (Fig. 6C,D; Rédei, 1967; Wetzel et al., Observations on the im leaf epidermis provided another interesting insight (Fig. 6F) on plastids. No chlorophyll signal was visible in any epidermal cell type in the white sectors and even within a pavement or guard cell, the leucoplast size varied considerably. Similarly, chloroplasts of different sizes were visible in the pavement cells of green sectors. While the presence of chlorophyll in green sectors reinforced our earlier observations on wild type plants, it became apparent from the im mutant that plastid size cannot be considered as a consistent criterion for identification of either leucoplasts or chloroplasts within a tissue. Based on our investigations on the gl2 and im mutants it is clear that there is tremendous condition-dependent inter-convertibility between the chloroplasts and leucoplasts. In wild type Arabidopsis, whereas pavement cells in young cotyledons and leaves possess small chloroplasts, cells of older tissues may have an increased number of leucoplasts. Discussion The presence of chloroplasts in epidermal pavement cells of Arabidopsis has already been established (Pyke, 2009; Barton et al., 2016). The present work aimed to describe fresh resources and the basic subcellular relationships for PCC to facilitate further study on this under-researched subpopulation of chloroplasts. Based on the probes that have been used, a general picture of the PCC in Arabidopsis has emerged. They are found in a thin cytoplasmic sleeve and a reinforcing cytoskeletal mesh. PCC and stromules exhibit clear alignments with actin filaments. Interactions with the actin cytoskeleton have been suggested to play a role in both stromule extension and whole plastid movement (Kwok and Hanson, 2004a; Kadota et al., 2009). Indeed, the coordinated movement of the perinuclear plastids by the actin cytoskeleton has been reported to play a role in nuclear movement during the blue-light avoidance response (Higa et al., 2014). Despite this, we saw clustering of PCC around nuclei in only a small proportion of pavement cells, suggesting that nuclear movement either does not require PCC presence or requires a mass migration of PCC to the nucleus before it can occur. The actin Journal of Cell Science • Advance article delimited on its exterior by the cell boundary consisting of plasma membrane cytoskeleton also supports the cortical ER and the vacuolar membrane (Higaki et al., 2006; Ueda et al., 2010). The vacuolar membrane appears to press cortical PCC against the cell periphery and almost completely encloses more cell-central PCC. Though we saw that rapid vacuolar movement was often accompanied by the appearance of ‘tugging’ on PCC, the vacuole appears primarily to move freely over the plastid surface. This is in accordance with the idea of a shared association with the actin cytoskeleton but does not suggest a role for the vacuole in directed PCC or stromule movement. In contrast, as reported by Schattat et al. (2011) and reconfirmed here, the PCC and extended stromules are firmly enmeshed in the cortical ER and plastid behaviour appears to directly correlate with ER re-arrangement. Unlike the previous organelles discussed, no clear spatial association of the microtubules with PCC could be seen. Microtubules form a tight array of largely parallel filaments that traverse the cell periphery (Reviewed in Dixit and Cyr, 2004), and PCC seemed to sit below the plane of this array, with stromules extending either parallel or perpendicular to it. The potential for a microtubule effect on PCC should however be investigated further, as the ER has been implicated in stromule extension (Schattat et al., 2011) and an effect of microtubules on ER rearrangement has been reported (Hamada et al., 2014). The relationship between the outer membranes of the PCC, the ER and the vacuole creates a very dynamic field for membrane contacts and exchange of metabolites and ions. Ongoing investigations on the membrane contacts between the PCC and the surrounding endomembranes facilitated that will be reported elsewhere. All plastids are known to produce stromules (reviewed by Gray et al, 2001; Hanson and Sattarzadeh, 2011; Schattat et al., 2015) and these extensions have been suggested as interaction platforms for organelles such as nuclei, mitochondria and peroxisomes (Kwok and Hanson, 2004a, 2004b). Our present observations strongly suggest that these organelles associate only occasionally and rather transiently, and that mitochondria and peroxisomes show no preference for association with the stromule over the plastid body. On this basis we do not consider that there is a specific subpopulation of mitochondria and peroxisomes that are targeted particularly Journal of Cell Science • Advance article by the double transgenic lines reported here are providing interesting insights to the PCC body or stromule and maintain a sustained presence around them. However, though the individual perimeters of the stromule and plastid body were comparable, extension of a stromule does increase the total plastid perimeter. Though no preference is shown for association with a stromule, its extension may increase the total number of organelles with which a plastid can interact. Accumulation of plastids has been observed in the perinuclear region of hypocotyl cells and dark-adapted leaves of Arabidopsis (Kwok and Hanson, 2004b; Higa et al., 2014), and in pathogen challenged cells of tobacco (Caplan et al., 2008; Krenz et al., 2012; Caplan et al., 2015), however our present observations do not suggest the presence of a sustained PCC population around the nuclei under standard growth conditions. In addition, we have been unable to support the idea that stromules extended by the PCC in the perinuclear region display a specific configuration in relation to the nucleus. Whether the perinuclear aggregation of chloroplasts occurs in mesophyll cells in Arabidopsis, as well as whether this phenomenon is specific to stressed plants or plays a role in normal growth and development remain to be investigated. A major insight provided from this work involves the inter-relationship between chloroplasts and the differences in plastid behaviour between the pavement and mesophyll cells. In a model that considered PCC to be leucoplasts it was proposed that the epidermal layer acts as a sink for sugars produced by the mesophyll (Brunkard et al., 2015). In principle all chloroplasts are capable of photosynthesis, but their output of photosynthates might differ size and number (Pyke and Leech, 1994; Barton et al., 2016), it is likely small compared to that of the underlying MCC. Therefore, recognizing the plastids in pavement cells as chloroplasts does not negate a potential source-sink relationship between these two tissues. In order for continuous export of photosynthates from MCC and efficient photosynthesis, mesophyll cells must shuttle sugars to sink tissues (Ainsworth and Bush, 2011). The pavement cells, being close in proximity and potentially low in sugar production, could provide a readily accessible sink. Experiments done by Schattat and Klösgen (2011) showed that sugar induces stromule formation, so an accumulation of sugar in sink tissues may be accompanied by an increased stromule Journal of Cell Science • Advance article considerably. The sugar output from PCC is unknown but given their small frequency. In observations throughout the photosynthetic period, we found that PCC stromules increased in number throughout the day but that MCC maintained a consistently low stromule frequency. This observation, alongside the sugar responsiveness of stromules, suggests that while MCC mainly exported their photosynthates, the PCC responded to the consequent increase in levels of cytosolic sugar within the pavement cells. The idea was further tested by inducing stromules with exogenously fed 40 mM sucrose (Schattat and Klösgen, 2011; Schattat et al., 2011b). The stromule formation frequency increased significantly in PCC regardless of whether light was given during treatment. Interestingly, an increase in MCC stromule frequency occurred in the dark, but not when plants were exposed to light during treatment. This supports a model where mesophyll chloroplasts are capable of sugar-induced stromule induction, but while photosynthesis is active continuous export of sugars from the cytosol prevents sufficient accumulation for induction. We therefore propose that pavement cells act as a sink for sugars from the mesophyll during the daylight period. Investigations are underway to explore the physiological sugar regulated inter-chloroplastic relationship further. Another important implication of these results is that PCC behaviour is not representative of the majority of leaf chloroplasts under all conditions. Therefore, care should be taken when choosing an experimental tissue, and before applying a model based on PCC to all chloroplasts, the individual PCC and MCC responses should be compared. Our results also highlight the potential effect of growth and treatment Previous studies in Arabidopsis and Tobacco on stromule responses throughout the day-night cycle showed an increase in stromule frequency within the first few hours of light exposure and then consistent stromule frequency throughout the day (Schattat et al., 2012; Brunkard et al., 2015). This is in contrast to our observations of a gradual increase in stromules over the course of the entire day. Interestingly, both previous studies grew their plants under a 12 h light / 12 h dark photoperiod, while we used an 8 h light / 16 h dark. If the diurnal changes in cellular sugar status were responsible for the stromule response then photoperiod would certainly have an effect, as plant sugar metabolism adjusts to compensate for a longer night (Suplice et al., 2014). Photoperiod, as well as the time of day Journal of Cell Science • Advance article conditions on stromule responses. that tissue is collected, should therefore be taken into consideration when comparing observations of stromule frequency between experiments. Similarly, our observations of increased stromules in the mesophyll in response to sugar treatment appear to conflict with the statement by Brunkard et al. (2015) that mesophyll chloroplasts are not sugar responsive. However, as demonstrated here, mesophyll stromules are only induced by sucrose treatment in the dark. Brunkard et al. (2015) do not specify the lighting conditions for their treatment, but if they carried out their treatments in the light, then both observations are in accordance. It is therefore apparent that many factors, including photoperiod, time of observation and light exposure during treatment, influence plastid behaviour and that thorough reporting of all conditions is necessary to allow for comparison between studies. The suggested link between PCC behaviour, photosynthesis and sugar regulation also led us to explore the developmental aspects of chloroplast formation. The present view traces all plastids to a population of pro-plastids, which are colourless and so by definition, constitute leucoplasts. Further development of these colourless plastids into chlorophyll-containing chloroplasts occurs in a tissue and cell specific manner and requires input from nuclear encoded proteins (Jarvis and Lopez-Juez, 2013; Liebers et al., 2017). The linear route of leucoplasts and etioplasts greening into chloroplasts is thus well supported. Studies on plastids in the L1 layer of the shoot apical meristem and the epidermis of developing embryos suggest that this conversion occurs early in the epidermal cells, as either stacked grana or et al., 2010; Charuvi et al., 2012). Our observations with the gl2 mutant support chloroplasts as the standard plastid type in epidermal cells, as the presence of chloroplasts in the under-developed trichomes suggests the presence of PCC in the protodermal cells from which trichomes originate. It follows that loss of chlorophyll is responsible for the presence of leucoplasts in wild type trichomes, and that chloroplast to leucoplast conversion is part of normal development. We found that this phenomenon also occurs in senescent cells and tissues and in these cases is dependent upon a change in the cell physiology. As senescence is accompanied by breakdown of chlorophyll (Hörtensteiner, 2006) and the chlorophyll signal is relatively low in Journal of Cell Science • Advance article chlorophyll autofluorescence were seen in the plastids of these tissues (Tejos PCC (Barton et al., 2016), they are likely to be among the first plastids in which chlorophyll loss is visible during senescence. Based on our observations, it is clear that investigations of PCC in Arabidopsis must always take the growing conditions, tissue health and developmental stage of the plant into consideration. The use of the im mutant (Rédei, 1967; Wetzel et al., 1994) allowed us to reliably observe leucoplasts in pavement cells and indicated another facet of the leucoplast-chloroplast relationship. The two plastid types show considerable differences in behaviour but we determined that neither shape nor size was sufficient on its own to distinguish between chloroplasts and leucoplasts. This mutant also provides an interesting tool for future research to test, in a horizontal context, our hypothesis that differences in stromule response can be indicative of a source-sink relationship between cells. The white sectors with leucoplasts and the green sectors with photosynthetic chloroplasts lie side by side on a leaf in this mutant. Since the white sectors are non-photosynthetic, they represent sink tissues that should show a stromule response to accumulation of photosynthates from juxtaposed green regions. Conclusions Here we have provided a cell biological characterization of the small sub-population of chloroplasts in epidermal pavement cells of Arabidopsis. Plastid responses to changes in the cellular milieu and the phenomenon of basic characterization of chloroplasts in the pavement cells of Arabidopsis triggers several interesting questions and new approaches to understand their functional significance and their relationship with chloroplast populations in contiguous and subtending cells. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article plastid inter-convertibility have been highlighted through our observations. Our Methods Plant material and growth conditions Single and double transgenic lines were created through Agrobacterium mediated floral dip transformation (Clough and Bent, 1998) or through crossing. A complete list of plant lines used is provided in Table 1. The four different conditions for plant growth were as follows: (1) growth in sealed tissue culture boxes for 7-12 days or 21 days on sterilized Sunshine mix LA4 under a long day light regime (16 h light / 8h dark) for experiments on stromule frequency in response to sucrose; (2) growth for 7-12 days in petri dishes containing Murashige and Skoog basal medium (1962; Sigma M404) with B5 vitamins and 3% sucrose under a long day light regime for observations of the interactions between PCC and other organelles; (3) growth in pots for 6 to 7 weeks on Sunshine mix LA4 in a controlled chamber under a short day light regime (8 h light/16 h dark) for observations on diurnal plastid responses and leucoplast conversion in leaves. Diurnal stromule observations were taken on healthy leaves, while senescence observations were taken on older chlorotic leaves. All plants were grown under 120 μmol m-2s-1 light and at a temperature of 21°C. Confocal microscopy All fluorescence imaging was done on whole plants, with the exception of imaging of leaves over 3 weeks of age, which were detached and imaged TCS-SP5 confocal microscopy system equipped with a 488 nm Ar laser and a 543 nm HeNe Laser. GFP fluorescence was acquired between 500-520 nm, RFP fluorescence between 570-620 nm, YFP fluorescence between 530-550 nm and chlorophyll autofluorescence between 660-750 nm. mEosFP was photo-converted using a mercury lamp and the Leica fluorescence filter set D (Excitation 355 to 425 nm). The entire field of view was exposed to the conversion light for 10 to 15 seconds. All confocal images were acquired at a resolution of 1024 x 512 or 1024 x 1024 pixels. Three-dimensional (X,Y,Z) stacks were collected with a step-size of 0.99 μm and successive frames in X,Y,T time lapse series were 1.935 seconds apart. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article immediately. The plants were mounted in water and imaged using a Leica Images were processed using proprietary Leica (LSM SPII) software, ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012) and Adobe Photoshop CS6. Quick time 7 and Videator v2 (Stone Design Corp., New Mexico) were used for assembling and annotating time-lapse movies. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) SEM was carried out on unfixed, uncoated samples taken directly from the green house and observed using a Hitachi Tabletop TM-1000 system (Hitachi High-Technologies Corp., Tokyo). Calculation of cell depths Cell depths were calculated in the FNR-GFP RFP-ER background to allow visualization of the plastid populations and the cortical ER surrounding the cell borders. Z-stacks were taken with a step size of 0.4 μm from the upper epidermal surface to the bottom of the mesophyll cells in the cotyledons of 8 individual 10 day old seedlings. In ImageJ (Schneider et al. 2012), orthogonal views allowed the calculation of cell depth of between 15 and 20 cells of each type (pavement, guard or mesophyll) per stack based on the number of steps required to traverse the cell. Analysis of PCC and small organelles Time-lapsed images were collected for 41 to 321 frames. 1-3 PCCs per image set had stromules that remained in focus for the frames analyzed. Collection were followed for analyzing mitochondria and peroxisome encounters with PCCs respectively. The number of mitochondria or peroxisomes closely appressed to the PCC body or stromule was counted manually for each frame of the image sets using the ImageJ Cell Counter plugin (Kurt De Vos, 2001). The total number of close encounters between PCCs and either mitochondria or peroxisomes was summed and averaged over the total number of frames analyzed. 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the estimated means were calculated for the data. The perimeter of the body and stromule of PCCs was measured in the first frame of the time-lapse image sets used for counting the Journal of Cell Science • Advance article time for each frame was 1.935 seconds. A total of N=38 and N=10 PCCs average number of mitochondria juxtaposed to PCCs and the mean perimeters were reported with 95% confidence intervals. Stromule frequency: Treatment, image acquisition, calculation and statistical analysis Treatment of seedlings with 40mM sucrose or water controls was performed by carefully excising the entire plant from the soil and floating the plants in solution for 3 hours in either a dark chamber or under normal growth lighting. For consistency, plants were always taken at the end of the night cycle to begin treatment. For each condition under which stromule frequency was measured, N= 16 z-stacks were taken with a step size of 0.99 μm through the epidermis and the upper region of the mesophyll on the adaxial surface of the most expanded leaves. Standard deviation z-projections were obtained using ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012) and the number of plastids exhibiting or lacking stromules was counted manually for both the PCC and MCC populations in each image. The calculated stromule frequencies were transformed with the arcsin(√Freq) function according to Schattat and Klösgen, (2011). 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the estimated mean and statistical significance (Two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni test) were assessed using the transformed data. The mean and CI were back- transformed for representation in the figures. Acknowledgements for Mito:GFP, Sean Cutler for the GFP:Vac line Q5, Steven Rodermel for the im mutant, Martin Schattat for tpFNR:YFP and Rob Mullen for the RFP-NLS DNA probe. JM and KB gratefully acknowledge funding by NSERC, Canada. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article We thank Peter Dörmann for seeds of 35S-NPC4:GFP, David Logan References Ainsworth, E. A. and Bush, D. R. (2011). Carbohydrate export from the leaf: A highly regulated process and target to enhance photosynthesis and productivity. Plant Physiol. 155, 64-69. Barton, K. A., Schattat, M. H., Jakob, T., Hause, G., Wilhelm, C., Mckenna, J., Máthé, C., Runions, J., Van Damme, D. and Mathur, J. (2016). Epidermal pavement cells of Arabidopsis have chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 171, 723-726. Bisalputra, T., Downton, W. J. S. and Tregunna, B. (1969). The distribution and ultrastructure of chloroplasts in leaves differing in photosynthetic carbon metabolism. I. Wheat, Sorghum, and Aristida (Gramineae). Can. J. Bot. 47, 15-21. Bowes, B. G. and Mauseth, J. D. (2008). Plant Structure – A Colour Guide, 2nd Edition. London, UK: Manson Publishing, Ltd. Brunkard, J. O., Runkel, A. M. and Zambryski, P. C. (2015). Chloroplasts extend stromules independently and in response to internal redox signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 10044-10049. Caplan, J. L., Mamillapalli, P., Burch- Smith, T. M., Czymmek, K., and DineshKumar, S. P. (2008). Chloroplastic protein NRIP1 medi- ates innate immune Caplan, J. L., Kumar, A. S., Park, E., Padmanabhan, M. S., Hoban, K., Modla, S., Czymmek, K. and Dinesh-Kumar, S. P. (2015). Chloroplast stromules function during innate immunity. Dev. Cell 34, 45-57. Charuvi, D., Kiss, V., Nevo, R., Shimoni, E., Adam, Z. and Reich, Z. (2012). Gain and loss of photosynthetic membranes during plastid differentiation in the shoot apex of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 1143-1157. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article receptor recog- nition of a viral effector. Cell 132, 449–462. Clough, S. J. and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735-743. Cutler, S.R., Ehrhardt, D.W., Griffitts, J.S., Somerville, C.R. (2000). Random GFP::cDNA fusions enable visualization of subcellular structures in cells of Arabidopsis at a high frequency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 97, 3718-3723. Dhanoa, P. K., Richardson, L. G., Smith, M. D., Gidda, S. K., Henderson, M. P., Andrews, D. W., and Mullen, R. T. (2010). Distinct pathways mediate the sorting of tail-anchored proteins to the plastid outer envelope. PLoS One, 5(4), e10098. Dixit, R. and Cyr, R. (2004). The cortical microtubule array: From dynamics to organization. Plant Cell 16, 2546-2552. Frederick, S. E. and Newcomb, E. H. (1969). Microbody-like organelles in leaf cells. Science 163, 1353-1355. Gao, H., Metz, J., Teanby, N. A., Ward, A. D., Botchway, S. W., Coles, B. C., Pollard, M. R. and Sparkes, I. (2016). In vivo quantification of peroxisome tethering to chloroplasts in Tobacco epidermal cells using optical tweezers. Geitmann, A. and Nebenfuhr, A. (2015). Navigating the plant cell: intracellular transport logistics in the green kingdom. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 3373-3378. Gray, J. C., Sullivan, J. A., Hibberd, J. M. and Hansen, M. R. (2001). Stromules: Mobile protrusions and interconnections between plastids. Plant Biol. 3, 223-233. Gunning, B. E. S. (2005). Plastid stromules: video microscopy of their outgrowth, retraction, tensioning, anchoring, branching, bridging, and tipshedding. Protoplasma 225, 33-42. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Plant Physiol. 170, 263-272. Gunning, B., Koenig, F. and Govindjee (2007). A dedication to pioneers of research on chloroplast structure. In Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration: The Structure and Function of Plastids, Vol 23 (Ed. R. Wise and J. Hoober), pp. xxiii-xxxi. Dordrecht: Springer. Hamada, T., Ueda, H., Kawase, T. and Hara-Nishimura, I. (2014). Microtubules contribute to tubule elongation and anchoring of endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in high network complexity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 166, 1869-1876. Hanson, M. R. and Sattarzadeh, A. (2011). Stromules: Recent insights into a long neglected feature of plastid morphology and function. Plant Physiol. 155, 1486-1492. Higa, T., Suetsugu, N., Kong, S. G. and Wada, M. (2014). Actin-dependent plastid movement is required for motive force generation in directional nuclear movement in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 4327-4331. Higaki, T., Kutsuna, N., Okubo, E., Sano, T. and Hasezawa, S. (2006). Actin microfilaments regulate vacuolar structures and dynamics: Dual observation of actin microfilaments and vacuolar membrane in living Tobacco BY-2 cells. Hodges, M., Dellero, Y., Keech, O., Betti, M., Raghavendra, A. S., Sage, R., Zhu, X.-G., Allen, D. K. and Weber, A. P. M. (2016). Perspectives for a better understanding of the metabolic integration of photorespiration within a complex plant primary metabolism network. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 3015-3026. Hörtensteiner, S. Chlorophyll degradation during senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 55-77. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 839-852. Jaipargas, E.-A., Mathur, N., Bou Daher, D., Wasteneys, G. O. and Mathur, J. (2016). High light intensity leads to increased peroxule-mitochondra interactions in plants. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 6. Jarvis, P. and López-Juez, E. (2013). Biogenesis and homeostasis of chloroplasts and other plastids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 787-802. Joo, J. H., Wang, S., Chen, J. G., Jones, A. M. and Fedoroff, N. V. (2005). Different signaling and cell death roles of heterotrimeric G protein α and β subunits in the Arabidopsis oxidative stress response to ozone. Plant Cell 17, 957-970. Kadota, A., Yamada, N., Suetsugu, N., Hirose, M., Saito, C., Shoda, K., Ichikawa, S., Kagawa, T., Nakano, A. and Wada, M. (2009). Short actin-based mechanism for light-directed chloroplast movement in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 13106-13111. Kost, B., Spielhofer, P. and Chua, N.H. (1998). A GFP–mouse talin fusion protein labels plant actin filaments in vivo and visualizes the actin cytoskeleton in growing pollen tubes. Plant J. 16, 393–401. Kwok, E. Y. and Hanson, M. R. (2004a). In vivo analysis of interactions 4, 2. Kwok, E. Y. and Hanson, M. R. (2004b). Plastids and stromules interact with the nucleus and cell membrane in vascular plants. Plant Cell Rep. 23, 188195. Lawson, T. (2008). Guard cell photosynthesis and stomatal function. New Phytol. 181, 13-24. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article between GFP-labelled microfilaments and plastid stromules. BMC Plant Biol. Lawson, T., Simkin, A. J., Kelly, G. and Granot, D. (2014). Mesophyll photosynthesis and guard cell metabolism impacts on stomatal behaviour. New Phytol. 203, 1064-1081. Liebers, M., Grübler, B., Chevalier, F., Lerbs-Mache, S., Merendino, L., Blanvillain, R. and Pfannschmidt, T. (2017). Regulatory Shifts in Plastid Transcription Play a Key Role in Morphological Conversions of Plastids during Plant Development. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 23. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00023 Logan, D. C., Leaver, C. J. (2000).Mitochondria-targeted GFP highlights the heterogeneity of mitochondrial shape, size and movement within living plant cells. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 865-871. MacDonald, M. S. (2003). Selected photobiological responses. In Photobiology of Higher Plants, pp. 274-301. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. Mano, S., Nakamori, C., Hayashi, M., Kato, A., Kondo, M. and Nishimura, M. (2002). Distribution and characterization of peroxisomes in Arabidopsis by visualization with GFP: Dynamic morphology and actin-dependent movement. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 331-341. Marques, J. P., Dudeck, I. and Klösgen, R. B. (2003). Targeting of EGFP Marques, J. P., Schattat, M. H., Hause, G., Dudeck, I. and Klösgen, R. B. (2004). In vivo transport of folded EGFP by the ΔpH/TAT-dependent pathway in chloroplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1697-1706. Mathur, J. and Chua, N.H. (2000). Microtubule stabilization leads to growth reorientation in Arabidopsis trichomes. Plant Cell 12, 465–477. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article chimeras within chloroplasts. Mol. Gen. Genomics 269, 381-387. Mathur, J., Mathur, N. and Hulskamp, M. (2002). Simultaneous visualization of peroxisomes and cytoskeletal elements reveals actin and not microtubulebased peroxisome motility in plants. Plant Physiol. 128, 1031–1045. Mathur, J. (2005). The ARP2/3 complex: giving plant cells a leading edge. Bioessays 27, 377-387. Murashige, T. and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473-797. Osteryoung, K. W. and Pyke, K. A. (2014). Division and dynamic morphology of plastids. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 443-472. Paila, Y. D., Richardson, L. G. and Schnell, D. J. (2015). New insights into the mechanism of chloroplast protein import and its integration with protein quality control, organelle biogenesis and development. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 1038–1060. Pyke, K. A., Leech, R. M. (1992). Nuclear mutations radically alter chloroplast division and expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 99, 1005-1008. Pyke, K. A., Rutherford, S.M., Robertson, E.J. and Leech, R. M. (1994). arc6, a fertile Arabidopsis mutant with only two mesophyll cell chloroplasts. Plant Pyke, K. A. and Leech, R. M. (1994). A genetic analysis of chloroplast division and expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 104, 201-207. Pyke, K. A. (2009). Plastid Biology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Raghavendra, A. S. and Padmasree, K. (2003). Beneficial interactions of mitochondrial metabolism with photosynthetic carbon assimilation. Trends Plant Sci. 8, 546-553. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Physiol. 106, 1169-1177. Rédei, G. P. (1967). Biochemical aspects of a genetically determined variegation in Arabidopsis. Genetics 56, 431-443. Rérie, W. G., Feldmann, K. A. and Marks, M. D. (1994). The GLABRA2 gene encodes a homeodomain protein required for normal trichome development in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 8, 1388-1399. Robertson, E. J., Rutherford, S. M. and Leech, R. M. (1996). Characterization of chloroplast division using the Arabidopsis mutant arc5. Plant Physiol. 112, 149-159. Sage, T. L. and Sage, R. F. (2009). The functional anatomy of Rice leaves: Implications for refixation of photorespiratory CO2 and efforts to engineer C4 photosynthesis into rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 756-772. Schattat, M. H., Barton, K., Baudisch, B., Klösgen, R. B. and Mathur, J. (2011a). Plastid stromule branching coincides with contiguous endoplasmic reticulum dynamics. Plant Physiol. 155, 1667–1677. Schattat, M. H. and Klösgen, R. B. (2011b). Induction of stromules formation by extracellular sucrose and glucose in epidermal leaf tissue of Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 115. stromules: stroma filled tubules extended by independent plastids. Plant Signal. Behav. 7, 1132-1137. Schattat, M. H., Griffiths, S., Mathur, N., Barton, K., Wozny, M.R., Dunn, N., Greenwood, J. S. and Mathur, J. (2012b). Differential coloring reveals that plastids do not form networks for exchanging macromolecules. Plant Cell 24, 1465–1477. Schattat, M. H., Barton, K. A. and Mathur, J. (2015). The myth of interconnected plastids and related phenomena. Protoplasma 252, 359–371. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Schattat, M. H., Klösgen, R. B. and Mathur, J. (2012a). New insights on Schellmann, S. and Hülskamp, M. (2005). Epidermal differentiation: trichomes in Arabidopsis as a model system. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 49, 579-584. Schimper, A. F. W. (1883). Über die entwickelung der chlorophyllköerner und farbköerper. Bot. Zeit. 41, 105–113. Schimper, A. F. W. (1885). Die entwickelung und gliederung des chromatophorensystems. In Jahrbücher Für Wissenschaftliche Botanik (ed. H. Fitting, W. Pfeffer, N. Pringsheim and E. Strasburger), pp. 2-49. Berlin: G. Borntraeger. Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. and Eliceiri, K. W. (2012). NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Met. 9, 671-675. Sinclair, A. M., Trobacher, C. P., Mathur, N., Greenwood, J. S. and Mathur, J. (2009). Peroxule extension over ER-defined paths constitutes a rapid subcellular response to hydroxyl stress. Plant J. 59, 231-242. Smith, B. N. (2005). Photosynthesis, Respiration, and Growth. In Handbook of Photosynthesis 2nd Edition (ed. M. Pessarakli), pp. 671-676. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group. Belmont: Brooks Cole. Suplice, R., Flis, A., Ivakov, A. A., Apelt, F., Krohn, A., Encke, B., Abel, C., Feil, R., Lunn, J. E. and Stitt, M. (2014). Arabidopsis coordinates the diurnal regulation of carbon allocation and growth across a wide range of photoperiods. Mol. Plant 7, 137-155. Szymanski, D. B., Lloyd, A. M. and Marks, M. D. (2000). Progress in the molecular genetic analysis of trichome initiation and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 214-219. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Solomon, E. P., Berg, L. R. and Martin, D. W. (2010). Biology 9th Edition. Tejos, R. I., Mercado, A. V. and Meisel, L. A. (2010). Analysis of chlorophyll fluorescence reveals stage specific patterns of chloroplast-containing cells during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Biol. Res. 43, 99-111. Ueda, H., Yokota, E., Kutsuna, N., Shimada, T., Tamura, K., Shimmen, T., Hasezawa, S., Dolja, V. V. and Hara-Nishimura, I. (2010). Myosin-dependent endoplasmic reticulum motility and F-actin organization in plant cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 6894-6899. Vaughan, K. (2013). Immunocytochemistry of Plant Cells. Dordrecht: Springer. Vick, J. K. and Nebenführ, A. (2012). Putting on the breaks: Regulating organelle movements in plant cells. J. Int. Plant Biol. 54, 868-874. Vitha, S., McAndrew, R. S. and Osteryoung, K. W. (2001). FtsZ ring formation at the chloroplast division site in plants. J. Cell Biol. 153, 111-119. Waters, M. T., Fray, R. G. and Pyke, K. A. (2004). Stromule formation is dependent upon plastid size, plastid differentiation status and density of plastids within the cell. Plant J. 39, 655-667. (1994). Nuclear-organelle interactions: the immuntans variegation mutant of Arabidopsis is plastid autonomous and impaired in carotenoid biosynthesis. Plant J. 6, 161-175. Wise, R. R. (2007). The diversity of plastid form and function. In Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration: The Structure and Function of Plastids, Vol 23 (ed. R. Wise and J. Hoober), pp. 3-26. Dordrecht: Springer. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Wetzel, C. M., Jiang, C.-Z., Meehan, L. J., Voytas, D. F. and Rodermel, S. R. Woo, K. C., Anderson, J. M., Boardman, N. K., Downton, W. J. S., Osmond, C. B. and Thorne, S. W. (1970). Deficient photosystem II in agranal bundle Journal of Cell Science • Advance article sheath chloroplasts of C4 plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 67, 18-25. Figures Figure 1. The presence of pavement cell chloroplasts in Arabidopsis A. Scanning electron micrograph of the petiole region of a cotyledon in the wrm mutant where epidermal cell detachment along the long axis results in B. A confocal image shows plastids with chlorophyll fluorescence (false coloured magenta) in a detached epidermal cell (arrow) from a cotyledon petiole in the wrm mutant. Chloroplasts in the mesophyll layer (arrowhead) are larger compared to the PCC. C. Representative image from a cotyledon petiole taken soon after a 8h dark period shows chloroplasts in the top portion of the pavement cell. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article single epidermal cells (arrow) curling out. D. An image from a cotyledon petiole taken after 4h of exposure to light shows PCC aligned along the bottom of the epidermal cell and thus appearing to lie over the MCC. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Size bars - B, C = 25; D = 50; A = 100µm. Figure 2. A general fluorescent protein aided assessment of pavement A. A collapsed 3D-confocal image stack of a leaf from a transgenic line expressing a plasma membrane targeted GFP (35S-NPC4:GFP) shows the relative sizes and positions of PCC (arrows), chloroplasts in guard cells and the mesophyll chloroplasts (e.g. square box). B. A representative image from a leaf showing the general F-actin cytoskeleton around PCC (arrow) and an inset ‘b’ showing a magnified view of F-actin cage around a single PCC. The underlying blue layer contains the high chlorophyll-containing MCC. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article cell chloroplasts and their surroundings C. Image from the double transgenic tpFNR:mEos-GFP:mTalin line shows the main chloroplast body and the elongated stromule aligned with a F-actin strand. D. Most PCC do not appear in the same section as cortical microtubules and a collapsed 3D stack of confocal images suggests their random dispersal in the cell at different planes. Relative to the PCC the MCC (arrow) appear large. E. A collapsed stack of 3D confocal images suggests that stromules (St) may align transiently with CMt over short distances. F. PCC (chlorophyll fluorescence in blue) appressed against the upper boundary of a pavement cell by the underlying green fluorescent vacuolar tubules and the underlying MCC. G. Lateral view of a pavement cell in the tpFNR:mEosFP-GFP:Vac line showing the peripheral localization of PCC (arrowheads) with extended stromules and subtending vacuolar tubules. H. A top down view of a pavement cell shows PCC with stromules engulfed by vacuolar tubules (See also Movie S3) surrounding achlorophyllous structures of the same size as PCC. J. Image acquired on an RFP:ER-GFP:Vac double transgenic shows the profile of an achlorophyllous structure suggested in ‘I’ is due to the vacuole surrounding an ER-body. K. Image of a PCC with an ER cage similar to that observed around MCC. L. Image of a chloroplast-containing PCC-body (blue) enmeshed in an ER cage (red) and with a contiguous ER channel (arrowheads). Journal of Cell Science • Advance article I. An image from the GFP:Vac transgenic line shows the membrane M. Image of a PCC (chlorophyll – blue) from the tpFNR:GFP-RFP:ER line with green fluorescent stromules extended into the ER channels. N. Image of the vacuolar tubules engulfing the nucleus and three PCC (arrowheads) in the peri-nuclear region. O. Image of PCC with and without extended stromules clustered around a nucleus in a tpFNR:GFP-RFP:NLS line. Abbreviations: CMt - cortical microtubules; ER - endoplasmic reticulum; Factin - filamentous actin; GC - Guard cells; PCC – pavement cell chloroplasts; MCC- mesophyll cell chloroplasts; Nu – nucleus; St - Stromule; Vt - Vacuolar tubule; Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Size bars (µm): A = 25; B – H, I, J, N, O = 10; b, K, L, M = 5. Figure 3. Observations on PCC in tpFNR:YFP-mito:GFP and tpFNR:mEosFP-GFP-PTS1 double transgenic lines of Arabidopsis. A. A snapshot from a time-lapse image sequence showing PCC (yellow) with stromules (St) and mitochondria (green) to estimate their possible interactivity. B. A snapshot of PCC (magenta) with stromules (red) and peroxisomes C. A diagrammatic depiction of the locations of the two organelles (red depicts either mitochondria or peroxisome) on either the main plastid body or the extended stromule that were used to build data for insights on their localization patterns. D. The average number of mitochondria (Mt) or peroxisomes (Px) in close juxtaposition to a PCC body or an extended stromule. Error bars represent the 95% CI for the estimated mean (N=38, N=10 respectively) Journal of Cell Science • Advance article (green) co-visualized for estimating their possible interactivity. Letters indicate significant differences between groups (P < 0.05) within a light treatments or cell type (a to d for PCC or light treatment, r to u for MCC or dark treatment). An asterisk indicates a significant difference (P < 0.05) Journal of Cell Science • Advance article between light treatments or cell types. Figure 4. Using stromule formation to assess the physiological relationship between epidermal and mesophyll layers plants grown under short day conditions. Error bars represent the 95% CI for the estimated mean (N=16). B. Hourly change in stromule frequency of PCC and MCC in response to treatment with a 40 mM sucrose solution. Error bars represent the 95% CI for the estimated mean (N=16) C. D. Stromule frequency of PCC (C) and MCC (D) in 21 day old plants treated with 40 mM sucrose or a water control for 3 hours. Plants were either Journal of Cell Science • Advance article A. Stromule frequency of PCC and MCC over an 8h light period in 6 week old kept in the dark or exposed to 120µmol m-2s-1 light during the treatment. Error bars represent the 95% CI for the estimated mean (N=16). Letters indicate statistically significant groups (p < 0.05) within cell types or treatments (a-d for PCC or Light, r-u for MCC or Dark). Asterisks indicate a Journal of Cell Science • Advance article difference (p < 0.05) between cell types or treatments. trichome cells in Arabidopsis expressing tpFNR:GFP and in the glabra2 (gl2) mutant epidermal cells. A. A flattened z-stack of 10 confocal images shows the base of a trichome, the epidermis and the mesophyll layers in an Arabidopsis (Columbia ecotype) plant expressing tpFNR:GFP. Panels 1, 2, 3, 4 show GFP (green) and chlorophyll autofluorescence (red), a bright field image and a merged image, respectively. Note the presence of chlorophyll fluorescence in the pavement cells of the epidermal layer but its complete absence in the trichome cell Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Figure 5. Images showing leucoplasts and chloroplasts in and around (panel 2). As shown by the stroma-targeted tpFNR:GFP probe mature trichomes in Arabidopsis possess leucoplasts only (panel1; green; arrowhead). B. A scanning electron microscope image of a stubby trichome ( * ) that has not completed its differentiation in the gl2 mutant. C. A short, collapsed trichome in gl2 similar to ‘B’ has plastids that exhibit chlorophyll autofluorescence (red) comparable to the fluorescence of chloroplasts in the sub-epidermal layers. D. A scanning electron microscope picture of a cell on a gl2 leaf ( * ) that appears to have entered the trichome differentiation pathway but did not progress to branching and maturation stages. Its collapse and enlargement suggest its continuation / reversion into a pavement cell fate. E. Image of a gl2 trichome similar to ‘D’ that has not completed its differentiation shows plastids with a chlorophyll signal (red) alongside a GFP:mTalin F-actin fluorescence (green). F. A gl2 mutant line expressing a plasma-membrane targeted GFP probe shows chlorophyll-containing plastids (red) in a putatively aborted trichome. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Size bars: A, B = 50 µm; C - F = 25 µm. clear differentiation between leucoplast and chloroplasts. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Figure. 6. Images from Arabidopsis wild type plants and mutants allow A. A group of physiologically compromised swollen PCC in a senescent cotyledon exhibit the clear separation of their GFP highlighted stroma and the chlorophyll contents. B. An image from a pavement cell in a senescing 16 day old cotyledon of an Arabidopsis plant expressing tpFNR:GFP shows several green leucoplasts (e.g. arrowhead) alongside a plastid exhibiting a green-red mix (panel 4) suggesting the presence of chlorophyll (red; panel 2). C. Image of young plants of the Arabidopsis variegated mutant im showing the characteristic green (g) and white (w) sectors containing chloroplasts and leucoplasts, respectively. D. Image of a leaf of the im mutant transformed with stroma targeted tpFNR:GFP shows green fluorescent sectors that contain mostly leucoplasts and regions with chloroplasts whose fluorescence is false colouration. E. A compressed confocal image stack of a portion of a leaf petiole in im shows lens-shaped chloroplasts (false coloured blue) and variously shaped and elongated green fluorescent leucoplasts that clearly lack chlorophyll. F. Confocal image of a variegated leaf from im shows chlorophyll in cells on the upper left that represent a white leucoplast rich sector whereas the right side of the image shows mesophyll chloroplasts. Chloroplasts that are intermediate in size between guard cell chloroplasts (boxed areas) and mesophyll chloroplasts are visible in the pavement cells in the lower left leaf sector. Chloroplasts in guard cells (similar to the 3 in boxed areas) appear in a typical curved pattern as compared to the scattered chloroplasts in neighbouring pavement cells. Size bars: A, B=5 µm; C=1 mm; D=100 µm; E= 20 µm; F =25 µm. Journal of Cell Science • Advance article fluorescence (blue) against a bright field background. Chloroplasts are absent Table 1. Transgenic lines and mutants of Arabidopsis used for assessing the subcellular environment around pavement cell chloroplasts Line Single transgenics Highlighted subcellular compartment Reference tpFNR:GFP Plastid stroma green tpFNR:YFP Plastid stroma yellow; Replaced GFP by YFP Plastid stroma green to red photoconvertible Plasma membrane green Marques et 2003, 2004 Schattat et 2011a Schattat et 2012b Gaude et 2008 tpFNR:mEosFP 35S-NPC4:GFP al., al., al., al., Double transgenics tpFNR:GFP x RFP:ER Plastid stroma green, ER lumen red tpFNR:GFP x RFP:NLS Plastid stroma green, Nuclear interior red tpFNR:YFP-T-Mito:GFP Plastid stroma matrix green tpFNR:mEosFP x GFP:PTS1 Plastid stroma green to red photoconvertible, Peroxisome matrix green Plastid stroma green to red photoconvertible, Vacuolar membrane green tpFNR:mEosFP x GFP:Vac yellow, Mitochondrial tpFNR:mEosFP x GFP:MAP4 Plastid stroma green to red convertible, Microtubules green tpFNR:mEosFP GFP:mTalin Plastid stroma green to photoconvertible, Actin cytoskeleton green Tonoplast green, ER lumen red x GFP:Vac-T-RFP:ER photo- red Schattat et al.2011; Sinclair et al., 2009 Marques et al., 2004; Dhanoa et al., 2010 Schattat et al., 2011a; Logan & Leaver, 2000 Schattat et al., 2012b; Mano et al., 2002 Schattat et al., 2012b; Line Q5 from Cutler et al., 2000 Schattat et al., 2012b; Mathur & Chua, 2000 Schattat et al., 2012b; Kost et al., 1998 Cutler et al., 2000; Sinclair et al., 2009 Immutans (im)-T-tpFNR:GFP Plastid stroma green Glabra2 (gl2)-T-tpFNR:GFP Plastid stroma green Crooked (crk) Wurm (wrm) Wetzel et al, 1994; Marques et al., 2004 Rerie et al., 1994; Marques et al., 2004 Mathur, 2005 Mathur, 2005 Journal of Cell Science • Advance article Mutant backgrounds J. Cell Sci. 130: doi:10.1242/jcs.202275: Supplementary information Supplementary Figures Supplementary Figure 1. The perimeter of PCC plastid bodies and stromules that were considered for analysis of mitochondria-PCC juxtaposition. The perimeters did not differ from one another and on average represented equal Error bars represent the 95% CI for the estimated mean (N=38). Journal of Cell Science • Supplementary information proportions of the exposed plastid surface area in these time-lapsed image sets. J. Cell Sci. 130: doi:10.1242/jcs.202275: Supplementary information Supplementary Movies All time-lapse movies are being played at 5 frames per second. M1. Chlorophyll containing plastids (false coloured in magenta) are readily observed in a pavement cell of the cotyledon petiole that has curled out of the M2. A pavement cell in the double transgenic tpFNR:mEosFP-GFP:mTalin line showed PCC alignment and motility along a F-actin strand. Journal of Cell Science • Supplementary information general epidermal plane in the Arabidopsis wurm mutant. J. Cell Sci. 130: doi:10.1242/jcs.202275: Supplementary information M3. Time-lapse sequence of a top down view of a pavement cell in a tpFNR:mEosFP-GFP:Vac line showing a single PCC with an extended stromule and the vacuolar tubules and vesicles in the neighbourhood. In this view the PCC M4. A lateral view showing several PCC in a tpFNR:mEosFP-GFP:Vac line being engulfed by dynamic vacuolar tubules that appear to flow over them. Journal of Cell Science • Supplementary information appears to lie above the vacuoles. J. Cell Sci. 130: doi:10.1242/jcs.202275: Supplementary information M5. A nucleus with several PCC, some with extended stromules around it. M6. Time-lapse sequence from a tpFNR:YFP-Mito:GFP line showing the general movement and occasional stoppings of mitochondria, suggestive of interactions, around the body and extended stromules of a PCC. Journal of Cell Science • Supplementary information Note that the stromules are not always extended towards the nucleus.