* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download text of chapter 2

Metastability in the brain wikipedia , lookup

Synaptic gating wikipedia , lookup

Development of the nervous system wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Optogenetics wikipedia , lookup

Neuroanatomy of memory wikipedia , lookup

Brain Rules wikipedia , lookup

Time perception wikipedia , lookup

Nervous system network models wikipedia , lookup

Neuroanatomy wikipedia , lookup

Visual memory wikipedia , lookup

Holonomic brain theory wikipedia , lookup

Neural correlates of consciousness wikipedia , lookup

Transsaccadic memory wikipedia , lookup

Visual servoing wikipedia , lookup

Embodied cognitive science wikipedia , lookup

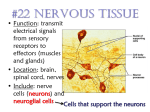

Channelrhodopsin wikipedia , lookup

Feature detection (nervous system) wikipedia , lookup

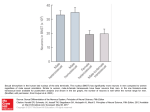

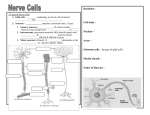

Optical illusion wikipedia , lookup

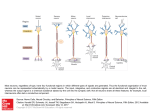

psych basics 6/23/2017 1 Chapter 2: Foundations of Psychology: Principles Relevant to Art "The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. John Berger, Ways of Seeing When artists and academic psychologists look at René Magritte's The Lovers, they probably notice different aspects of the canvas (Figure 2.1). Artists may observe the overall composition with its intersecting diagonals, and the skillful shading that helps give perspective to the shrouded figures. Perception psychologists and neuroscientists might notice how our eyes are drawn to the brightest parts of the image, the shrouds on the 'faces'. They would also note that one of many cues to depth used by Magritte (1898-1967) is occlusion, that is, objects in the background are covered up by those in the foreground. Cognitive psychologists are likely to notice inferences we make about the painting. For instance, most of us infer there are two faces covered by cloth, and a man is next to a woman in a pastoral scene. Psychoanalysts might notice that the faces are veiled and focus on how this adds remoteness to what seems to be a close romantic relationship. They would link this to Magritte's early experiences. This chapter is devoted to explaining some basics from the research of these three different groups: perception psychologists, cognitive psychologists, and psychoanalysts. We start by differentiating the three approaches in more detail. Figure 2.1 about here: René Magritte's The Lovers Perception psychologists and neuroscientists study the way our eyes and brain (the visual system) work and how the nervous system encodes images. One issue they have studied for more than a century is the way viewers distinguish foreground figures from the background in a picture. To do this, perception psychologists perform experiments searching for general principles of vision. New questions often arise from these experiments, and psychologists psych basics 6/23/2017 2 design new studies to refine their explanations of vision further. One example of their work was introduced in chapter 1 in the section about the Müller-Lyer illusion (Figure 1.7). Much has been learned about the visual nervous system partly because questions about how we see are some of the most interesting to humans, and partly because these issues have been investigated by many clever experimenters over many decades. Two main findings from this research are that: (1) seeing involves different modules (e.g., color in one module, shape another), and (2) neurons respond to rather specific visual inputs (e.g., some neurons respond to vertical lines; others to faces; Roberson, Davidoff, & Shapiro, 2004). In the second section of this chapter, we select and explain work of experimental cognitive psychologists about how ideas in art are conveyed and understood. Cognitive experiments reveal systematic principles used to interpret art, although these are not always tied explicitly to the nervous system (yet). For instance, Solso (1994) suggested there are three stages that characterize how we look at a picture. Stage 1 is when light enters our eyes and is converted into a neural code; stage 2 is when our eyes and brain work on these neural codes identifying objects in a scene; and stage 3 is when our personal and general knowledge influence the interpretation of the encoded image. Figure 2.2 is a "box-diagram" of this model, and also suggests how these stages can be applied to looking at Magritte's picture. Stage 3, the most cognitive stage, has many aspects including how the painting is classified, remembered, and related to other knowledge we have. Figure 2.2 about here -- Solso's cognitive model Some theories in psychology have been applied widely to art and are understood by artists and viewers as indicated in Chapter 1 when we considered intellectual traditions as an 'agreed' convention in art. Freud's (1856-1939) psychoanalysis about psychosexual psych basics 6/23/2017 3 development is one example and is the topic for the third section here because it is a popular theory among many art historians and artists in the 20th Century. Although we will review central tenets of Freud's psychoanalytic theory in detail later in the chapter, here we mention a few psychoanalytic suggestions that might have influenced René Magritte to paint faces behind shrouds and titled his painting The Lovers (Figure 2.1). Lloyd and Desmond (1992) suggest he was portraying his own difficulties with sexual relationships, and these psychoanalysts trace this difficulty to the early loss of his mother at age 13 (probably a suicide). Because his normal psychosexual development was curtailed early, psychoanalysts suggest that Magritte's work reflects that his psyche did not develop normally leading him to experience impoverished adult relationships. Section 1: Basics of the Human Visual System Relevant to Artists When someone looks at a picture, several steps are traversed by the eye and brain to register it in our understanding. The representation of this process that we describe here is a six-step model that unpacks Solso's (1994) Stage 2 (see Figure 2.3). It starts with converting light energy reflected from a picture, and ends with a percept shared with other viewers. The array of small units of light or pixels (1) of varying color and brightness become dots when represented in the nervous system (2); some of these dots are associated with each other and seen as lines (3); some lines are then interpreted as edges of objects (4); the objects are attached to a scene of related objects (5); and finally we give the scene an interpretation (6). These steps can be illustrated when viewing any picture, say, Magritte's painting The Lovers. When we look at Figure 2.1, the image enters our nervous systems as an array of pixels of white, blue, green, and brown light reflected from the page in step 1. Some of the pixels are grouped into dots (step 2) and some of these dots are organized into lines (3) such as those defining the necklines psych basics 6/23/2017 4 on the clothing worn by the couple. In the next step, edges are identified as boundaries between objects (4), say, the edges that distinguish the man and woman from the pastoral background. In the fifth step, our nervous systems note relationships among objects in Magritte's painting. In the last step (6), we may have several different interpretations of the image, in contrast to the fairly similar interpretations in steps 1 to 5. This is because we bring prior knowledge about the scene that may, or may not, be shared with others to give it meaning. For instance, one person might infer the couple are attending a formal occasion because the man is wearing a suit and tie; another might infer the location is somewhere with relatively high rainfall because of the abundant foliage. If these were our inferences, we might deduce that Magritte was depicting how people can feel at formal occasions when they are constrained by cultural traditions and concealing emotions that might interfere with the occasion. Figure 2.3 about here (block diagram of 6 steps of perception) Neuroscientists and perception psychologists investigating the visual system tend to think about the way our eyes and brain process the image step by step (Livingstone, 2003). The pixels-dots-lines-edges-scene-interpretation sequence is often chosen to describe perception, but sometimes events occur simultaneously, or in a different order. Most researchers consider this model as only a rough idea of the process of vision. To understand how these steps occur, we need to be acquainted with some neuroscience findings at both the micro- and macroscopic levels. At the microscopic level, how individual neurons work and communicate with each other are important basics that are applied at each step when perceiving pictures. At the macroscopic level, the eye and brain convey the visual message to us so that the marks on the canvas become a meaningful scene with two masked people. psych basics 6/23/2017 5 One important distinction that neuroscientists make is that early and later encoding in the visual system can differ. Early on, light is encoded into neural impulses by neural cells at the back of our eyes (step 1). The coded message is then passed on to other more central, but specific, parts of the nervous system that deal with visual information. Note that after the array of pixels enters the visual system through the receptor cells in the eye, neural codes are used in all subsequent steps of vision. These codes do not resemble the image itself, just as the word 'book' does not resemble the object being read. However, we recognize, and deal with, the coded neural information as a book. When the visual message arrives at the relatively late steps 5 and 6 where a coherent scene is seen and interpreted, neuroscientists think that the information is processed in two different, but parallel, streams (Livingstone, 2003, Zeki, 1999). One stream deals primarily with the identity of objects and the other deals primarily with movement and space in the scene. We have selected details about these steps that are relevant to art in the following paragraphs. How neurons work -- Microscopic level Characteristics of individual cells. Neuron is the name given to a cell in the nervous system. Although neurons differ in shape and size as illustrated in Figure 2.4a, they are similar in having three features (Figure 2.4b). These features also indicate function: (1) dendrites collect neural messages (electrical/biochemical) from neurons in a previous layer, (2) a cell body maintains housekeeping for the neuron (e.g., nutrition), and (3) an axon directs the message to later neurons in the chain (Figure 2.4b). Essentially then, each neuron sends a biochemical/electrical impulse to following neurons on the basis of impulses it receives from the neurons earlier in the chain. Each particular neuron fires whenever the sum of impulses from previous neurons is strong enough to pass its threshold of firing. A neural impulse is also psych basics 6/23/2017 6 called an 'action potential' because an 'action' occurs and 'potential' refers to the impulse as an electrical event. Neural firing is illustrated by the "are we there yet" cartoon of Calvin and Hobbes (Figure 2.5). Each neuron is similar to Calvin's father who silently amasses evidence of misbehavior from Calvin and Hobbes. After reaching his tolerance level, Calvin's father erupts with a loud rebuke. The father's explosive comment is like a neural impulse in the nervous system that comes after sufficiently strong biochemical messages occur from previous neurons in the chain. Figure 2.4 & Figure 2.5 about here - neurons and Calvin and Hobbes The code for visual information is based on how rapidly the neurons are firing, not on the size of the impulse. For instance, to indicate that light is dim in a part of an image, the particular neurons encoding that part fire less rapidly than for a part of the image indicating stronger light. When we look at Magritte's The Lovers, the left side of the shrouded heads (as we look at the picture) will lead to more rapid firing for neurons encoding that part of the image compared to neurons encoding the right side of the 'faces'. The neurons encoding the trees in the background will fire even less frequently. Figure 2.6 also shows the brighter parts of an image lead to a greater firing rate for cells representing that part of the scene. The reflected light in the cloud in the upper left of this photograph and the edge of the wave cutting diagonally across the picture (in a northwest/southeast direction), will cause more neural impulses than the darker parts of the image (Parkhurst, Law & Niebur, 2002). The lower panel illustrates a pattern that might be encoded by our neurons of the scene. Figure 2.6 about here -- Parkhurst et al. 2002 How do neuroscientists find out that a neuron responds best to a certain visual feature, such as a face or an edge? They put a very small recording electrode into a chosen location in psych basics 6/23/2017 7 the visual system and record how often the single cell fires to particular pictures. Look for instance at Figure 2.7. Washmuth, Oram, and Perrett (1994) show the number of neural impulses per second recorded from brain cells in the visual pathway of monkeys. The cell fired more frequently to pictures that included a face (about 50 impulses/ second); but it fired less when the face was occluded (< 5 impulses/second). In this case, the neuroscientists sometimes say that the neuron they recorded from is a face detector, and they know their electrode is located somewhere in the vision circuit used to identify faces. Figure 2.7 about here -- Washmuth et al -- neural firing Interactions among neurons. There are considerable interactions among the one trillion neurons in humans. Some estimate that, on average, there are 1000 preceding neurons that influence each cell (Goldstein, 2007). These interactions enable us not only to see the objects in our visual world, but to reduce the information overload we deal with routinely. Zeki (1999) suggests that reducing the overload is probably a key function of our vision, and many neurons send inhibitory messages to the next one down the chain. Inhibition is a chemical message at the cellular level that makes it harder for the next neuron to fire. Both excitatory and inhibitory interactions among neurons are important in understanding why we see more detail in the center of our visual field than in the outer edges (periphery). In the visual pathway, the number of neurons that influence each cell is greater in the periphery than in the center (Livingstone, 2003). For example, if you fixate the center of Magritte's picture in Figure 2.1, you will see more detailed features near the point of fixation than in the surrounding parts of image. The effect of this uneven distribution of neurons is to make very fine details visible in the center of your visual field while your peripheral vision is less adept at detecting details. On the other hand, cells in the periphery are more sensitive to psych basics 6/23/2017 8 any change in the brightness of light reflected by an image because they are influenced by more preceding neurons than cells in the center of the eye. You might have noticed this on a dark night when a starry sky stretches out above you. If, in the corner of your eye (the periphery), you notice a shooting star, you are likely to move your eyes automatically to get a better look with your more detailed central vision at the place in the sky where the shooting star appeared. Frequently, the shooting star seems to disappear because it is too faint to be seen in the center of your visual field. The shooting star movement was only detectable when there were relatively more neurons feeding the next level. This unevenness in sensitivity to brightness level (specialty of periphery of eyes) and to details (specialty of center of eye) is very important when looking at art because our eyes move to different parts of the picture as we look at it. The neurons in the center of your eye track the details that are important for later steps in perception while those in the periphery are encoding relatively small changes in brightness across the picture. Figure 2.8 shows the tracks of eye movements made when two people looked at Rembrandt's Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp. The viewers tended to center their vision on the faces of the medical students and Dr. Tulp (Molnar as cited in Solso, 1994). Eye tracking studies illustrate that the steps in vision are not completely automatic. Instead, what we see in a picture is guided by which parts of objects we encode in more detail compared to others. For instance, for Molnar's participants, the gowns and foreground of the canvas were hardly ever the focus of their eye movements. Rembrandt probably exploited this aspect of the visual system of viewers by making the faces and torso of the patient brighter, in essence privileging these parts of the image because the neurons encoding these parts of the visual field would fire more rapidly than those encoding the darker parts of the image. psych basics 6/23/2017 9 Figure 2.8 Rembrandt's Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp How the visual system works at a Macroscopic level. First steps in the visual pathway. The macroscopic description of vision involves considering the eye and brain structures that are important when we see. The inner lining at the back of the eyeball is called the retina (from the Latin word for net) and the neurons there are arranged in three compact layers. The first layer, registering the light, is comprised of cells that convert radiant energy (light) into neural impulses. Humans have two types of these light-sensitive receptor neurons: rods and cones. The cones are concentrated in the center of the eye and used for detailed vision and color. The rods are found in greater proportion in the periphery of the eye, firing very sensitively to the light but failing to encode color or refined details that are registered by the cones. The next two layers of neurons in the retina (bipolar and ganglion cells) carry the message about the visual world to the brain. Enhancing edges. When we look at a picture, the crosstalk among these three neural layers in the eye cleverly enhances edges between areas of differing brightness (Livingstone, 2003). Two additional types of neurons in the eye help accomplish this crosstalk effect. Enhancing borders in the image is one way the visual system systematically modifies the physical brightness pattern in a scene making it easier for us to identify objects. Look at the four bars of changing brightness in Figure 2.9a. The bars look outlined with a dark line on the darker side and a light line on the lighter side of each border. Your visual system has put in those lines; they are not there in the physical image (Figure 2.9b & c). The special process is called lateral inhibition and biases us toward detecting changes in an image. Although you do not need to know details of how lateral inhibition works, a fuller understanding of this early perceptual transformation may be helpful. Figure 2.9d presents psych basics 6/23/2017 10 Goldstein's (2007) explanation of how this works. In sum, lateral inhibition makes boundaries between areas of changing brightness stand out. Our visual system at the retina essentially 'looks' for edges so that objects and people can be identified. This tendency to 'search' for edges is even characteristic in newborns just a few hours old (Haith, 1980). Figure 2.9 -- lateral inhibition leading to edge enhancement - Goldstein Visual information reaches the brain. The coded message about the image is passed on to our brain via the axons of the third layer of the retina (ganglion cells). These relatively long axons convey the visual message with its enhanced edges to the middle of the brain to a structure called the thalamus. The thalamus is a general receiving area for all sorts of perceptual information, including sound and touch. It is situated below the cortex and thus called a subcortical structure (Figure 2.10). Here the coded information about the image is kept in an orderly fashion with 'files' for colors, lines, movement, and location of the light represented systematically in the six different layers of a special set of thalamic cells devoted to vision: the structure is called the lateral geniculate nucleus. This nucleus also keeps track of which eye the information came from by sending the information from each eye to three of the layers. The coding here is like filing receipts into separate folders, one for your leisure account, another for insurance; then separating insurance into car, house, and life. At this subcortical level, neuroscientists have shown more lateral inhibition occurs enhancing the edges in the image further than would be accomplished by the retina's initial sharpening process. Figure 2.10 about here -- schematic drawing of visual system The message is then sent on to the cortex (outer layer of cells in the brain) at the back of the brain (occipital lobe) for further processing. The first place in the cortex where visual information comes is called V1 (V for vision, 1 for 1st; Zeki, 1999). Here a big picture view is psych basics 6/23/2017 11 represented where lines are highlighted (e.g., outline of a cadaver, face of a surgeon in Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp, Figure 2.8). Figure 2.11 summarizes the steps so far. Note that the neural encoding of what we see has been passed on and already modified many times. The message then radiates to other parts of the brain where separate features of the image such as colors, object identification (face or table), and motion are analyzed in more detail. Livingstone (2003) and Zeki (1999) characterize this late process as two parallel streams of visual information: one for what objects are in the image and the other for where objects are in the image (Figure 2.12). In Rembrandt's Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp (Figure 2.8), for instance, viewers identify the edges where brightness changes, then determine that these are boundaries for faces, a surgical table, and a cadaver in their what stream. In the where stream, the location of these objects is determined with the medical students behind and to the left of the teacher and the cadaver in the front. Rembrandt skillfully indicates depth by using several cues such as placing nearer objects lower in the painting and providing brighter contrasts between collars and gowns for medical students in the front compared to those in the back. Experiments that support the existence of two streams include one by Moutoussis and Zeki (1997) in which people recognized color slightly before movement indicting that the timing for the streams can differ. In sum, our eyes encode reflected light as dots, then, in concert with our brain, we identify edges of objects and integrate information to recognize a coherent scene as we move through later steps in the nervous system that is devoted to vision. Figure 2.11 and Figure 2.12 about here -- Visual Pathway and Visual Streams Section 2: Basics of Cognitive Psychology Relevant to Artists psych basics 6/23/2017 12 Cognitive psychologists are concerned with how people understand a picture. Specifically, they study how we pay attention to particular aspects of an artwork, how we remember it, imagine it, categorize it, and think about it. The way we use language to describe a photograph, sculpture, painting or drawing is also a topic of interest to experimental cognitive psychologists. We consider each of these topics in turn because paying attention to, remembering, imagining, categorizing, and thinking about an artwork are critical when we interpret art (stage 3 of Solso, 1994; Figure 2.2). Attention. One way to discover how viewers pay attention to an artwork is to follow their gaze. For instance, the eye movement study of Molnar (as cited in Solso, 1994) illustrates that the faces of the medical students depicted in the picture were of prime interest to viewers in Rembrandt's Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp (Figure 2.8). In another eye-tracking experiment, Nodine et al. (1993) found that art experts tend to scan differently than amateurs. The experts looked more broadly at the images (i.e., less focus on faces) and found compositional patterns more readily than the amateurs. Attention is also relevant to art when we determine what is an ideal amount of visual variability to make an image pleasant for us. Those who study aesthetics suggest that too little variation in color or shape or motion in an image can be boring while too much may be offputting to an audience (Biederman & Vessel, 2007). Also artists sometimes emphasize a particular feature in their picture to call attention to it, or even to shock viewers. For instance, artists painting in the Fauve style, such as Matisse, used complementary hues to intensify surrounding areas as in Open Window, Collioure (Figure 1.11). This nontraditional choice of colors might also shock viewers. Another way artists manage attention is in their selection of psych basics 6/23/2017 13 subject matter. In The Lovers (Figure 2.1), Magritte might have chosen the particular setting to encourage viewers to think about romantic relationships or about traditional occasions. Memory: Accuracy. One way cognitive psychologists have examined principles of memory is to compare picture recognition to word recognition. The general finding is that picture memory is superior. For instance, Shepard's (1967) participants scored 96.7% in a recognition test of more than 600 pictures that were shown only one time, even when the memory test was 4 months later. In contrast, the recognition score for words shown one time each was only about 88% when testing was immediately after the words were presented. Standing (1970) tried to stump his participants by showing them 10000 images, each only once. The individual error rates for recognizing pictures were as low as 4%, and no greater than 15%, even when recognition tests were given several days later. In other studies, what is being remembered was found to be critical, not just whether the material is verbal or pictorial. Abstract ink blots or snowflakes are remembered less well than faces (Yin, 1969). Faces (51% accuracy) were recognized better than landscapes, objects, and paintings (about 25% accuracy for each category) in a recent study (Laeng el al., 2007). In both the Yin and Laeng et al. studies, the experimenters concluded that familiarity with a type of material is important for memory. Another way memory is enhanced is by the emotional content in the image to be remembered. For example, Christianson and Loftus (1991) found that a picture of a person in a traumatic accident is remembered better than the person in a neutral setting. . No doubt you noticed considerable variability in the memory scores for participants in the experiments that were summarized in the previous paragraphs. Although it is possible that people in the most recent study have worse memories than those in the earlier ones, this is psych basics 6/23/2017 14 unlikely. One reason is given by Neisser (1997) when he notes an international trend for people to become increasingly sophisticated in dealing with picture information because we are surrounded by graphic images -- on cups, billboards, plastic bags, t-shirts -- far more than in the past. A more likely reason that different memory scores were found in different studies is that it is difficult (or maybe impossible) to equate for familiarity with the material for each participant in an experiment. Memory in the Creation of Art. In our context, it is known that training in artistic skills improves visual memory. Pérez-Fabello and Campos (2007) found that fifth year art students scored significantly better than first years on five tests of visual imagery and memory. Familiarity with visual images would be increasing with each year in school. For centuries, artists have studied previous master works in museums, sometimes copying these - both studying and copying increase familiarity with images. Sometimes a later work appears to be a new version of an earlier picture. Figure 2.13 illustrates that Picasso painted Amboise Vollard (art dealer) with similar compositional features, color and tone as Cezanne's earlier portrait (Thompson, 2006). Figure 2.13 -- Portraits of Amboise Vollard -- Cezanne, Picasso Conversely, artists sometimes depict scenes from memory. It is likely, for instance, that the cave painters in Chauvet (ca. 30000 years BCE) produced animal figures from memory, unless they were incredibly effective in training wild animals (Figure 2.14). Even when artists work at the scene, they have to rely on their visual memories to some extent. For example, one aim of the Impressionist painters was to capture momentary reflections of light in a scene, and they preferred painting at the scene en plein air. However, because light reflections are psych basics 6/23/2017 15 momentary, they would have to paint many details from memory to complete a picture worthy of display such as Claude Monet did in Impression, Sunrise (Thompson, 2006). Figure 2.14 here -- Chauvet cave drawing Interestingly, some painters, such as Escher, reported drawing and painting from memory most of the time (ref). He described this as using his imagination. An example is the etching Belvedere in which buildings and people are constructed without direct models (Figure 2.15). Indeed, no models exist for some of the seemingly sound architectural structures because of the impossible three-dimensional shapes Escher implied in this picture. Similarly, Edgar Degas (1834-1917) portrayed ancient Sparta and the mountain on which Spartan infants were hardened off by their parents in Young Spartans Exercising, even though he had never been to Greece (Thompson, 2006). Figure 2.15 here - M.C. Escher's Belvedere Artists often use themselves as models for their work according to Leonardo. For instance, Escher's own hands were readily available when he created Drawing Hands and are probably represented in the etching (Locher, 1981; Figure 1.3). Consider Figure 2.15, Matisse's Self-Portrait, 1918. He used a mirror to produce this picture. However, a careful look shows us that he painted his left thumb as part of the hidden right hand that is holding the palette. Perhaps, it was easier for Matisse to paint his dominant thumb because it was manipulating the paintbrush and in his line of vision, rather than painting the right thumb that was only visible in the mirror, requiring him to dart back and forth from mirror to canvas. Some fascinating experiments could be conducted to compare the level of detail, the compositions, and the colors of paintings created from memory to those when the subject was present during the artist's creation. psych basics 6/23/2017 16 Figure 2.16: Matisse Self-Portrait 1918 Memory compartments. Another finding about memory relevant to art is the separate compartments of memory that have been identified by current researchers. Memory for knowledge (declarative) is one compartment; and, memory for actions (procedural) is the other (Schacter, 1987). Evidence that we keep memories in separate compartments comes from individuals who have a brain injury such as those unfortunate enough to have visual agnosia. These patients lose a major part of their knowledge memory, being unable to recognize shapes, but they remember actions well such as how to draw, to play tennis, and to feed themselves. Drawings of visual agnosics like that shown in Figure 2.17 confirm this: the patient copied a picture as marks on a page, but could not recognize the object (Zeki, 1992). Figure 2.17 -- drawing by visual agnosic People with normal memories appear to have subdivided the knowledge memory compartment with one section for personal memories (autobiographical) and the other for general information (Tulving, 1985). For instance, when Pizarro saw Turner's paintings of wintry scenes in the 1870s, he would have later recalled both the artistic techniques Turner used (generic information) as well as his own circumstances when he saw the paintings (Signac as cited in Werner, 1999). Later, he created many snow scenes himself. These were related to both his generic memory for Turner's artistic techniques, and his autobiographical memory that was probably boosted by emotional content because Signac reports that Pizzarro was "enthralled" by Turner's art when he was living in London during the Franco-Prussion war. Personal memories often flash into our thinking when we look at art, such as remembering the person we were with, and our circumstances, when we first saw the picture. Separately, we recall information from the generic knowledge compartment such as the artwork belongs to the psych basics 6/23/2017 17 Impressionist period. The two main compartments of memory, knowledge and action, are often fused in our recalls, as are the subdivisions. This compartmentalization and parallel recall from different parts of our memory might account for why a picture has different impacts on different people. Imagery. Cognitive psychologists who study imagery have demonstrated that we process imagined and real objects very similarly (Kosslyn, 1980). Shepard and Metzler (1971) asked participants to say whether or not pairs of two-dimensional drawings depicting threedimensional solids were the same except that one was rotated. In all the pairs, the objects were either the same or mirror images of each other (Figure 2.18). They found that as the rotational difference between two identical pictures increased, participants took proportionally longer to indicate the two pictures were the same. On average, it took about one second for participants to rotate the images 60o. For instance, if the two objects were presented at exactly the same orientation, it took one second to respond (i.e., marginal time to see and respond); and if one was upside-down (180o), it took roughly 4 seconds (1 second marginal time plus 3 seconds to rotate 180 o = 3 x 60 o). This suggests the participants rotated one object in their imagination to decide if it was the same as the other. In another study, Spivey and Geng (2001) showed that eye muscle movements were similar for visible and imagined objects. They asked participants to look at a briefly presented set of four different objects in corners of a display (triangle, arrow, oval, rectangle). Participants were then shown three of these objects and asked to identify the tilt of the absent object. The participants made eye movements to the position of the absent object 30% of the time. Spivey and Geng suggest that looking at the location of the absent object might be an effort to re-awaken the memory for the tilt of the image. psych basics 6/23/2017 18 The similarity between imagined and real objects does not mean that the visual cognition is the same in every way because the way the measurements were made (time to do a task, eye movements) could be limiting our understanding about how viewers deal with real versus imagined objects. However, based on the experiments mentioned, we can say that artists who rely on visual images will not produce inferior likenesses when representing imagined objects compared to real ones, especially with their art school practice. Figure 2.18 about here -- Shepard & Metzler solids example Categorization and Language. Because categorization is fundamental for thinking, cognitive psychologists are interested in how people classify objects, especially how language and culture influences their classification (MacLaury, 1991). Two extreme positions about the influence of language and culture on visual categorization have been explored experimentally as well as many positions between these poles. One extreme is that visual forms are completely dependent on the language and culture of the viewer such as when Alaskans can identify nine types of snow that are not discriminated by Floridians (Whorf, 1956). In this strong form, the proposition that vision depends completely on language is easy to reject because words for colors and shapes from one language can be translated into most other languages (Roberson et al., 2002). At the other extreme is the notion of universal visual forms, or prototypes, that are completely independent of language. For instance, Rosch (1973) emphasizes the centrality of basic level categories, such as a triangle, arguing that regular geometric forms are perceptually important. She found that people identify objects at a basic level more accurately and rapidly than when the objects to be identified are at a subordinate (equilateral vs isoceles triangle) or superordinate level (regular geometric shapes). In one test of this universality-of-perception idea, Rosch asked 40 people from the Dani tribe in Papua New Guinea to sort shapes like those psych basics 6/23/2017 19 in Figure 2.19. The Dani language does not have words for these shapes and they did not spontaneously sort them into the square, triangle, circle that would be used by westerners. Then Rosch trained the Dani participants to sort the shapes into the three western categories. She concluded that the best exemplars of the "good shapes" (on the left of each row) were learned faster than other items. She labeled these "prototypes" for each Western category. Later evidence from a study of the Himba people in Namibia failed to confirm Rosch's conclusion (Roberson et al.). Like Dani, the Himba language does not have terms for circle, square or triangle, and the participants did not use the western categories when they were asked to sort the items spontaneously. However in a training period similar to Rosch's where the Himba participants were taught the Western categories, Roberson et al. found that the prototype shapes took longer to learn than the other items in that set. One reason Roberson et al. suggest for the relative difficulty in classifying the prototypes is that regular geometric shapes are rarely found in nature. Overall, they concluded that circles and squares are unlikely to be perceptual universals independent of language and culture. Figure 2.19 -- Rosch figures for cross-cultural studies Metaphor in art. Conveying a meaning that is not a strictly literal interpretation of an image or word is a very effective way to communicate. Like perceptual illusions, metaphors are understood by almost everyone: they are not random communications. In fact, Glucksberg (1998) found that people cannot ignore metaphoric meanings when judging whether a phrase could be literally true. Participants took longer (about 1/10 second) to indicate that a metaphor like "some jobs are jails" does not have a literal meaning compared to a non-metaphoric statement like "some jobs are birds". This suggests that the intended meaning of the metaphor (lack of freedom in a job) was understood automatically and interfered with the factual decision psych basics 6/23/2017 20 about the phrase. Metaphoric meanings in visual art are probably compelling also. For instance, art historians (e.g., National Gallery of Art, 1995) have suggested that the balance in Vermeer's painting The Woman Holding a Balance has a religious meaning (Figure 2.20). In keeping with 17th Century Dutch ideas, Vermeer was probably encouraging viewers to conduct their lives thoughtfully and with moderation. The jewelry in the foreground is a symbol of worldly goods. The painting in the background is of the Last Judgment reminding us that we are accountable for our actions at death. Because the images of worldly goods and eternal judgment are separated by the scale, Vermeer's message may be that we should carefully consider the balance between the worldly and the eternal. Compared to people who have not viewed the canvas, those who inspect the painting might be motivated to think more about daily decisions concerning short-term luxuries given that they will face the last judgment at some time. This hypothesis could be tested. Figure 2.20 about here -- Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance Many cognitive psychologists who study metaphor focus on language and literature, not visual images. They find that metaphoric meanings are not only intended, but the preferred meaning, in ambiguous phrases. When we hear "my lawyer is a shark", we understand that the lawyer is vicious and tenacious, not that the lawyer is a marine animal. Visual metaphors are also likely to be preferred by viewers. This is another testable hypothesis and might involve comparing meanings understood by viewers in representational art, abstract art, and randomlygenerated marks. Another example of metaphor is the title of Martin's (2002) book Picasso's War that is about the artist's huge mural Guernica (Figure 2.21). Picasso lived in Paris throughout the 1930s and 1940s, never serving as a soldier, however Martin conveys in the title of his book psych basics 6/23/2017 21 that Picasso's artistic efforts were warlike. Picasso, himself, described some figures in Guernica as universal metaphors: "the bull is not Fascism, but it is brutality and darkness; ... the horse represents the people". The people Picasso refers to were civilian inhabitants of the Basque town Gernika killed during a blitzkrieg raid by combined German and Italian forces in 1937. Picasso had agreed to create a large artwork for the Spanish pavilion at the World's Fair in Paris and explains that "The mural is for the definite expression and resolution of a political problem and that is why I used symbolism". He chose no direct images of the raid, but rather metaphoric references especially those related to traditional rituals. Picasso surmised that metaphoric images would be compelling to viewers. Figure 2.21 about here -- Picasso's Guernica Sometimes artists are more direct in their use of metaphors such as when Magritte explored relationships between language and art in The Interpretation of Dreams. He shows six objects and inscribes a mismatched name underneath each such as a picture of a bowler hat labeled "snow" and a lighted candle labeled "ceiling". This is also an example of how psychoanalysis may have influenced Magritte. According to Freud, dreams, visual art, and word associations are all ways unconscious thoughts can be revealed, and here, Magritte weaves them together. It is also possible that Magritte was simply pointing out the arbitrariness of sounds assigned to objects in language (Thompson, 2006). We hope that reading this book is a watershed in your understanding of how art and psychology inform each other. We do not mean literally that the book is an area drained by a river. Instead, you understand that we hope our book will enlighten your views permanently about scientific findings concerning perception and cognition that are relevant to art. Section 3: Basics of the Freudian Psychoanalytic Approach Relevant to Artists psych basics 6/23/2017 22 Basic psychoanalytic principles. Because Freudian psychoanalytic theory is popular with some art historians and has also influenced the creation of paintings such as those of Dali and Picasso, we describe it some detail (Freud, 1916). Freud’s principal contribution to contemporary psychology was the discovery of the “talking therapy” (ref). That is, by relating and re-living the events of everyday life to a trained analyst, we can begin to unravel the mysteries of our psyches, much of which are hidden in our unconscious minds. Indeed, Freud argued that there was no such thing as an unmotivated act, the unconscious mind always being fertile and commanding. The unconscious, however, is never directly observable, only inferred through several mechanisms, the most important of which are dream analysis, memory lapses, slips of the tongue, and other “verbal” mistakes. Analysis of dreams can reveal the activity of unconscious desires, and here Freud makes his early comparison of artistic activity as being similar to dream activity. Both are essentially play activity, making something for the fun of it. Indeed studio professors often use the expression, “play with your imagination” as a guiding principle in crafting artistic work. For Freud, both artistic work and dream work are propelled by the pleasure principle which helps to reduce tension pent up by impulses that have been suppressed in the psyche. This is not to say that artistic endeavors and dream production are identical. They do differ, as art is filled with imagination and creativity whereas dreams are not tangible nor particularly creative. To help us understand the working of the unconscious mind, Freud introduced the concept of defense mechanisms (i.e., ways in which the psyche protects itself from the intrusions of the real world). Chief among these, from the point of view of artists, are sublimation and repression. Sublimation refers to the channeling of hostile impulses, often sexually defined, into a more acceptable form. For instance, the main subliminal activity for psych basics 6/23/2017 23 artists is their artwork where they can “play” with destructive impulses in a safe manner. Picasso, Klee, and Dali all manifested these impulses, according to some psychoanalysts, through their contorted images. Klee's Lost in Thought (Figure 1.6) is an example of this. The school of surrealism is often seen as psychoanalysis’s main sojourn into artistic interpretation for this reason (Martin, 2001). Repression on the other hand refers to motivational forgetting where the unconscious mind actively suppresses real memories. These two mechanisms, sublimation and repression, often go hand-in-hand in the creation of artistic work according to psycho-analytic thinking. The product, a work of art, may reflect, therefore, both the outpouring of destructive impulses that were repressed but in the creation of art now take on a more acceptable symbolic form, such as the shape of Klee's oversized eyes in his self-portrait that suggest vulvae (Figure 1.6). This might be a sublimation of his desire for adult sexual interaction that had to be postponed by separation from his fiancée in order to serve in his country's war effort. In addition to unconsciousness as a major cornerstone of psychoanalysis, we must add the dynamics of infantile sexuality and the Oedipus complex. Freud saw the development of personality as defined by early events in childhood, and these had sexual overtones. Chief among these was the Oedipus complex or the incestuous desire of the male child for his mother; and, for girls, the Electra complex that is the incestuous desire of the female child for the father. So strong are these impulses and so clearly inappropriate that children repress them early-on. They continue to serve as the nexus of repressed tensions until satisfied in adulthood through successful seeking of a life’s soul mate. Magritte's The Lovers may illustrate this (Figure 2.1). Failure to resolve these tensions completely can reveal themselves in behavior where perfection is the ultimate goal and its failure the cross one bears for sexual insecurities. psych basics 6/23/2017 24 The meticulousness of Vermeer’s work is a commonly cited example (Figure 2.20). Another tenet of Freudian sexuality theory is the primal scene. The primal scene (a child’s first view of sex) is often viewed by psychoanalysts as a mirror into the psyche of the artist. Titian’s sexually erotic paintings serve as an example where primal scene elements (cupids, facing dolphins) are considered to indicate Oedipal insecurities (Figure 2.22, ref). Figure 2.22 about here -- Titian's Rape of Europa In addition to surrealism as an art form replete with psychoanalytic overtones, the Dada movement of the 20th Century can be viewed as regressive behavior, another psychoanalytic defense mechanism, where a person returns to a stressless time in one’s life. For the Dadists, the regression was usually to childhood where child’s play could be viewed as escape from the materialism that led to the destructiveness of World War 1. Jean Arp illustrates one facet of this style of art in Collage Arranged According to the Laws of Chance. In order to free art from strict geometric formulae he placed roughly shaped squares into a haphazard arrangement and glued them to the paper. As Dada film-maker Richter (1961) says, "for us chance was the 'unconscious mind' that Freud had discovered in 1900." Their efforts were "to restore to the work of art its primeval magic power and to find a way back to the immediacy it had lost through contact with ... classicism". Summary We have selected some basic information about perception, cognition and psychoanalysis to provide background for readers for the chapters that follow. In the next section of the book, we considering light, color and perspective in more detail. psych basics 6/23/2017 25 Portfolio Exercises 1. Identify two artworks by the same artist, one that was painted from memory and one when the subject was present. Compare these. OR Using sketches made by an artist in preparation for a later work, indicate which aspects of the sketches were omitted and which were included, suggesting reasons why. Martin's book on Picasso's Guernica could be used for the second option here. 2. Explore visual metaphors for viewers of art. Ask several people to write down the meaning they find in an artwork. For some of the group, tell them to interpret every object literally; for others, suggest that the objects have metaphoric meaning. You can use the Vermeer painting in Figure 3. The way that art historians categorize groups of artists and art works illustrates cognition. For instance, Sturgis and Clayson (2000) mention this when they point out most art museum curators use chronological or geographic guidelines to organize their galleries. Report on the organization of the National Gallery of Art indicating ways this is helpful to and hinders viewers of art to understand the works displayed. 4. Indicate how Caillebotte's On the Europe Bridge illustrates the Solso's stages for looking at art, indicating how the 6 steps of perception (Figure 2.3) and aspects of cognition and psychoanalysis might be applied to a viewer. 5. Choose one or two works of Frieda Kahlo and (a) indicate how a perception psychologist would describe the process of looking at the work, and (b) how a psychoanalyst might interpret her artwork.