* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

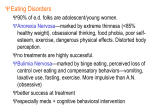

Download Anorexia nervosa during adolescence and young adulthood

Human brain wikipedia , lookup

Autism spectrum wikipedia , lookup

Time perception wikipedia , lookup

History of neuroimaging wikipedia , lookup

Biology of depression wikipedia , lookup

Cognitive neuroscience wikipedia , lookup

Neuroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

Neuroplasticity wikipedia , lookup

Metastability in the brain wikipedia , lookup

Haemodynamic response wikipedia , lookup

Sports-related traumatic brain injury wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychology wikipedia , lookup

Clinical neurochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Externalizing disorders wikipedia , lookup

Impact of health on intelligence wikipedia , lookup

Aging brain wikipedia , lookup

Neurogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Causes of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Bulimia nervosa wikipedia , lookup