* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Scientific Case against the Global Climate Treaty

Economics of climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Heaven and Earth (book) wikipedia , lookup

Climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Climate resilience wikipedia , lookup

ExxonMobil climate change controversy wikipedia , lookup

Low-carbon economy wikipedia , lookup

Climatic Research Unit email controversy wikipedia , lookup

German Climate Action Plan 2050 wikipedia , lookup

Michael E. Mann wikipedia , lookup

Soon and Baliunas controversy wikipedia , lookup

2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference wikipedia , lookup

Climate change denial wikipedia , lookup

Climate change adaptation wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on human health wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Economics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Global warming controversy wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Climate sensitivity wikipedia , lookup

Mitigation of global warming in Australia wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Tuvalu wikipedia , lookup

Fred Singer wikipedia , lookup

Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme wikipedia , lookup

Climatic Research Unit documents wikipedia , lookup

Media coverage of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming wikipedia , lookup

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

Physical impacts of climate change wikipedia , lookup

Global warming hiatus wikipedia , lookup

Global Energy and Water Cycle Experiment wikipedia , lookup

General circulation model wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

Global warming wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Politics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Attribution of recent climate change wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Instrumental temperature record wikipedia , lookup

Business action on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change feedback wikipedia , lookup

The Scientific Case against the

Global Climate Treaty

by S. Fred Singer

A Report from

The Science & Environmental Policy Project

Fairfax, Virginia

July 1999

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

OVERVIEW

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Climate is Forever Changing

Computer Models Don't Work

Other Human Influences Have Been Ignored

Rising Temperatures Could Have Positive Effects

Higher CO2 Levels May Not be "Dangerous"

Drastic Reductions in Energy Use…

… And Huge Economic Burdens on the Poor

Adapting to Climate Change

Farming the Ocean

THE UNDERLYING SCIENCE.

There is No Detectable Anthropogenic Warming

The Climate Treaty Goal

Natural Climate Variations

Human Influences

Explaining the Discrepancy

Satellite vs. Surface Data

Climate Observations vs. Computer Results

Historically, a Modest Warming is Beneficial

Control of Atmospheric CO2

Adjusting to Climate Change

UPDATE(1999)

Update on Climate Science

Economic Benefits from Global Warming: A Post-IPCC Re- Evaluation

The Kyoto Protocol is Ineffective

REFERENCES

PREFACE

The purpose of this essay is to demonstrate the absence of a sufficient scientific basis for

the Global Climate Treaty or for the kind of hasty and drastic bureaucratic "solutions"

arising from the December 1997 Conference of the Parties (COP-3) in Kyoto, Japan.

During more than two dozen seminar lectures presented in the United States and Europe

during the past two years, I found that audiences - both scientists and non-scientists responded most favorably when they could see the actual data supporting some of the

major scientific conclusions about climate change. Those conclusions are that:

•

There is no current global warming and little to be expected in the future.

•

The past, both recent and geologic, has seen large and rapid natural changes in

temperature.

•

Any onset of warmer temperatures would be expected to produce a drop in sea

level, not a rise.

•

The science of climate change is not "settled" or "compelling," and there is hardly

any consensus within the informed scientific community.

At this point, policymakers who promote the Kyoto Protocol appear determined to

impose severe economic hardships on much of the world's population through energy

taxes and energy rationing. The United States Senate, which ultimately must be

persuaded to ratify the Protocol, has voted 95-0 against such schemes, in the absence of

scientific justification. Many labor unions, industries and thoughtful citizens appear to

agree with the Senate.

It is my hope that readers, after examining the evidence for a manmade climate change or rather the lack of it - will reach the same conclusion.

S. Fred Singer, Ph.D., July 1999

OVERVIEW

The announced objective of the 1992 Global Climate Treaty (officially known as the

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) is to "achieve stabilization

of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent

dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system" (emphasis added).

The problem for policymakers is that no one knows what constitutes a "dangerous"

concentration of greenhouse gases. There exists, as yet, no scientific basis for defining

such a concentration, or even for knowing whether it is more or less than current levels.

Just the same, efforts are now underway to establish a protocol for reducing emissions of

greenhouse gases, focused mainly on carbon dioxide (CO2) from the burning of fossil

fuels by industry, electric power plants, home heating and cooking, automobiles, and

other road and farm vehicles.

To effectively reduce CO2, such an emission control scheme, with its legally binding

targets and timetables still to be decided, will be extremely costly and have a detrimental

economic impact on much of humankind. It risks ruining national economies, driving

manufacturing and other industrial operations into less regulated countries (with the

perverse effect of harming the environment in those countries), and ultimately costing

citizens hundreds of billions of dollars.

Regulatory costs, although initially borne by industrial and agricultural producers, will

eventually be passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices. The loss of jobs,

combined with a higher cost of living, will cause severe hardship, especially for the

poorest among us. Such economic sacrifices cannot be justified by current scientific

evidence. Indeed, scientists continue to put forth new theories to explain why global

temperature is not rising, even though greenhouse theory says it should.

The Global Climate Treaty, signed at the 1992 "Earth Summit" in Rio de Janeiro, rests on

three propositions that are either questionable or demonstrably false.

1: The Climate Treaty supposes that a human influence has been detected in the

climate record of the last hundred years, thereby validating the computergenerated predictions of a major future warming. But the climate has not

warmed significantly over the last half-century, and not at all over the last 20

years, in contrast to theoretical predictions.

2: It further supposes that any future warming would produce catastrophic

consequences, including droughts, floods, hurricanes, rapid and significant sea

level rise, the collapse of agriculture, and the spread of tropical disease. But

the climate record of the past 3,000 years appears to contradict all these

assertions. Historically, warmer temperatures have been beneficial for human

welfare and the development of civilization.

3: It presumes - with no scientific definition - to know which atmospheric levels

of greenhouse gases are "dangerous" and which are not. To stabilize CO2

concentration at present levels, 30 percent above pre-industrial values, would

require a drastic reduction of emissions and of energy use - more than 60

percent worldwide. But again, the historical record indicates that higher levels

of CO2 - and they have been much higher in the past - may in fact provide

benefits. Some scientists, including the late Roger Revelle, known as the

father of greenhouse warming, have speculated that some of these benefits

have already turned up in improved agricultural yields.

Let's take a broader look at these points. The main conclusion of the UN-sponsored

science advisory group, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is that

"the balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate." This

artful but essentially meaningless phrase has been misread by policymakers as proof that

computer models predicting a warming of 1 to 3.5 degrees Celsius by the year 2100 have

been validated. Such confusion is understandable. The IPCC Policymakers Summary

juxtaposes that phrase with the results of climate model calculations of future warming,

even though such a connection is specifically denied in the body of the 1996 IPCC report

(p. 434).

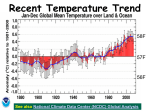

Such misinterpretations to the contrary, the global temperature record of this century,

which shows periods of both warming and cooling, can best be explained in terms of

natural climate fluctuations, caused by the complex interaction between atmosphere and

oceans, and perhaps stimulated by variations of solar radiation that drives the Earth's

climate system. [Fig. 1]

The weather satellite record of global temperatures, now spanning nearly twenty years,

shows no global warming trend, much less one of the magnitude that computer models

have led us to expect. The discrepancies between satellite observations and conclusions

drawn from computer calculations are so large as to throw serious doubt on all computermodeled predictions of future warming. Yet this discrepancy is never mentioned in the

IPCC Policymakers Summary; indeed, the Summary does not even admit the existence of

satellites.

Extrapolate the maximum allowed temperature trend from satellites to the year 2100 - the

"worst-case" scenario - and one might estimate an increase in global average temperature

of close to 0.5 degree Celsius - one-half the very lowest IPCC estimate. But 0.5 degree C

is barely detectable and completely inconsequential.

Moreover, any calculated warming will be reduced by the cooling effect of volcanoes.

Even though we cannot predict the occurrence of a volcanic eruption, we have sufficient

statistical information about past eruptions to estimate their average cooling effect; yet

this is one of several factors not specifically considered by the IPCC.

Are warmer temperatures necessarily bad? History shows us that human health and

human activities, especially agriculture, thrive during warm periods and falter during cold

ones. Infectious diseases are not related to temperature, but to poor hygienic practices,

lacking public health services, and, ultimately, poverty. A warming trend should lead to a

reduction in severe storms as the equator-to-pole temperature differences diminish. Also,

new research indicates that warmer temperatures would likely cause sea levels to fall, not

rise, as ocean evaporation increases precipitation over the poles and thickens the ice caps

of Greenland and Antarctica.

With climate change - and climate has often changed - the traditional route for

humankind has been simply to adapt. What is more, if it should become advisable to limit

the increase of atmospheric CO2, it might be more cost-effective to speed-up CO2

absorption into the oceans than to resort to energy rationing. Recent successful

experiments in fertilizing the ocean with micronutrients indicate that in the near future it

may be possible to not only draw down CO2 but to increase phytoplankton and fish

populations at the same time, thereby deriving commercial benefits from what was once

considered a problem.

Fig. 1 Global temperature versus time, as

determined from surface measurements.

The temperature changes are referred to

an arbitrary baseline.

Three different compilations are shown:

IPCC [1996]14,

GISS [Hansen and Lebedeff, 1987] and

Hasselmann [1997]27.

While all three records show the

remarkable warming before 1940, likely a

natural recovery from the cooling of the

"Little Ice Age," the records differ

considerably after 1940.

The differences between these records

illustrate some of the uncertainties in the

"global" climate record caused by the

selection and treatment of the data.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Climate is Forever Changing

We start with the observation that climate is forever changing, in many cases for reasons

we do not yet understand. External changes are brought about by the variability of the

sun, by volcanic eruptions, and, more rarely, by impacts of large asteroids or comets. But

on the time scale of years and decades, the most important changes arise from

complicated interactions between the atmosphere and the ocean; the El Niño events that

cause global changes in temperatures and rainfall are a good example.

On a longer time scale, the Earth has experienced some seventeen glacial episodes - Ice

Ages - in the last 2 million years. The variability of this past climate can be demonstrated

by examining tree rings, ice cores, and ocean sediment cores, all of which show evidence

of large and rapid temperature changes, even in recorded history - i.e. during the past

3,000 years. "Global" thermometer records have been available only since about 1880,

and much of the world (particularly in Asia and Africa) temperature data were logged

only sporadically, if at all. Even today large portions of the southern hemisphere and the

oceans are not monitored regularly. It is only in the last 20 years that we have had truly

global temperature data of the lower atmosphere from weather satellites.

Here is what the temperature data tell us: There has been a sharp warming from about

1880 to 1940, which is generally assumed to be a natural recovery from the "Little Ice

Age," a period of much colder temperatures that began around 1450. After the 1940 peak,

temperatures fluctuated, generally declining till about 1975 when there may have been a

sudden increase [Fig. 1]. Surface thermometers show such an increase lasting into the

middle 1980s; satellite data, however, backed up by observations from balloon-borne

instruments, show no increase whatsoever since 1979, and even a slight cooling.

There is still fierce debate about the discrepancy between surface data and satellite

temperature trends, but there is considerable evidence that the surface-based

thermometers, generally located at airports near cities, have been contaminated by the

"urban heat island" effect, which produces warmer temperatures locally. Climate records

corrected for this effect show maximum temperatures occurring around 1940, rather than

in the 1980s.

Computer Models Don't Work

Three-dimensional climate models that run on fast computers, the so-called General

Circulation Models (GCMs), have become much more sophisticated but still do a poor

job of representing the atmosphere. Their results differ widely, some showing a warming

of 1.5 degrees C or less, others of 4.5 degrees C or more. Because these models suffer

from poor spatial resolution - about 300 km - and an incomplete knowledge of cloud

physics, computer modelers cannot depict actual clouds but must instead "parameterize"

cloudiness, which accounts for much of the wide range of GCM results. The GCMs also

implicitly incorporate a positive feedback from atmospheric water vapor (the most

important greenhouse gas), which greatly amplifies the effect of a CO2 increase. In

reality, the feedback may well be negative, instead of positive.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has tried to explain the discrepancy

between observed and calculated temperature changes. In its first assessment, in 1990, it

simply ignored the satellite data and pronounced the observations and calculations to be

"broadly consistent."

The second and most recent assessment, published in 1996, no longer uses this phrase.

Instead, the IPCC tries to explain the difference between observations and theory by

introducing the cooling effects of anthropogenic sulfate aerosols, i.e. particles derived

largely from sulfur pollution produced by burning coal. It reduces the calculated "best"

warming trend from 0.3 C down to 0.2 C per decade, which is still in disagreement with

the satellite results. The IPCC also appeals to a supposed similarity of observed and

calculated temperature patterns and concludes that "the balance of evidence suggests a

discernible human influence on global climate." This ambiguous phrase has been widely

used to argue that the climate models produce results validated by observations. The

models are still inadequate in representing the real atmosphere, however, and no such

validation has occurred.

Just a year after the IPCC published its 1996 report, it has become apparent, on the basis

of recent computer studies, that the discrepancy between observations (showing no

warming trend) and theory (projecting a 0.2 to 0.3 C temperature increase per decade)

can no longer be explained by the assumed cooling effects of sulfate aerosols.

So what could be causing the gap? One set of explanations relies on effects internal to the

models, principally their inadequate treatment of clouds and water vapor. It is thought

that, if the models are improved, the positive feedback from water vapor would be

reduced, or even reversed, resulting in a climate sensitivity (i.e., temperature increase for

a CO2 doubling) of perhaps less than 1 degree C. Such temperature changes would be

barely detectable in view of the noisiness of the natural variations, and would be quite

inconsequential in their impact on climate.

The other set of explanations relies on external effects, principally caused by the 11-year

cyclical variations of solar ultraviolet radiation, or on the corpuscular emission from the

sun, the so-called "solar wind." Ultimately, these solar variations produce changes in

cloudiness or in atmospheric ozone, which can more directly affect the climate.

These two sets of explanations have very different consequences, and call for very

different policy responses. With the science largely unsettled, there is urgent need for

further research.

Other Human Influences Have Been Ignored

There are other greenhouse gases, in addition to carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels:

nitrous oxide from agricultural fertilizers, various halocarbons, and methane from oil and

gas operations, cattle raising and rice growing. International control efforts focus almost

exclusively on CO2, yet methane has increased more than 100 percent in the past century

and, on a per-volume basis, is 20 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2.

Aside from raising the level of greenhouse gases, an expanding population is changing

the ratio between cropland and forests, and thereby the reflecting power ("albedo") of the

surface. Growing air traffic is changing the chemical composition of the lower

stratosphere and may be producing sufficient contrails and cirrus clouds to show climate

effects. Even the diversion of river water can affect ocean circulation, and thereby

climate.

It is the task of research scientists to decide which of the many human influences are

important enough to be incorporated into climate models. For example, if the Aswan

Dam, by reducing the flow of the Nile, increases the already high salinity of the

Mediterranean, can its outflow through Gibraltar disturb the North Atlantic circulation

and affect North American and European climate, as has recently been suggested?

Rising Temperatures Could Have Positive Effects

Possible climate changes from human activities need to be considered from the

perspective of natural changes. The geologic record shows natural changes that were

larger and more rapid than those predicted by many computer models, and certainly

larger than can be expected on the basis of extrapolation of observed temperature trends.

Nevertheless, one should examine the potential impact of even a moderate temperature

increase.

Judging from the climate record of the last 3,000 years of human history, climate

consequences of a greenhouse warming should be generally beneficial. One would expect

severe weather to be less frequent because of (calculated) reduced equator-to-pole

temperature gradients. In fact, the frequency and intensity of hurricanes have decreased

over the past 50 years, although the reason for this is not known.

The most feared consequence of global warming has been a catastrophic rise in sea level,

resulting in coastal flooding and the disappearance of some islands. But new research

indicates that increased ocean evaporation would lead to more rain--and therefore to more

ice accumulation in the polar regions. As such, sea levels may actually drop. An

empirical study of sea level change and sea-surface temperatures of the past century

appears to point in that direction.

As far as agriculture is concerned, the combination of warmer weather and increased

CO2 would be beneficial. More CO2 promises rapid plant growth and, at the same time,

reduced water consumption because of reduced evapo-transpiration from leaves. The

climate warming that has been calculated would be most noticeable at higher latitudes,

primarily in the winter and at night, and would result in fewer frosts and a longer growing

season. Farmers can adjust to local climate changes - as they have in the past - with

improved technology and proper crop selection.

Higher CO2 Levels May Not Be "Dangerous"

One of the often expressed concerns has been that ongoing atmospheric changes could

reach a "dangerous" level that might cause climate to become extremely unstable, or

precipitate a sudden switch to a new climate state that would be detrimental to human

existence.

Again, looking at the climate record, there have been many large climate fluctuations, but

nothing that would lend support to the idea of a climate "surprise." If anything, the

variability of climate was greater during the last Ice Age, when CO2 levels were less than

200 parts per million, than during the most recent 10,000 years of the warm interglacial

(the Holocene), with CO2 levels at 280 ppm.

The geologic record does not indicate that CO2 levels higher than the present level (of

350 ppm) would be "dangerous." In fact, some 500 million years ago the planet

experienced CO2 levels as high as 15 times the present level: they have been declining

ever since, reaching a secondary peak of about 1500 ppm some 200 million years ago.

If we cannot tell whether higher levels of carbon dioxide are better or worse than present

or pre-industrial levels, there is little point to mounting elaborate schemes to control CO2

emissions.

Drastic Reductions in Energy Use...

The IPCC has determined that maintaining the present atmospheric concentration would

require that CO2 emissions be reduced by well over 60 percent worldwide and kept at

that value. Any lesser reduction would only slow down the ongoing increase of CO2 in

the atmosphere. But even a politically more palatable target of 550 ppm, much talked

about in the IPCC report, would require a CO2 reduction of some 50 percent, with a

corresponding reduction in the use of energy.

When the Conference of Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change

(Global Climate Treaty) held their first meeting in Berlin in 1995 (COP-1), it was

decided to exempt, or at least defer, developing countries from the obligation to stabilize

or reduce CO2 emissions. But since their emissions will very rapidly exceed those of

industrialized countries - by the year 2010 - emission control schemes become purely a

political exercise without any scientific basis.

This is quite evident from the fact that there is no scientific guidance on how to define

and avoid a "dangerous" level of CO2 - the announced goal of the Climate Treaty.

...And Huge Economic Burdens on the Poor

Reducing the emission of CO2 - or even stabilizing CO2 at the present level - would put

huge economic burdens on the industrialized nations and their citizens. If an emissions

trading scheme is put in place, which allows industrialized nations to buy unused permits

from developing nations, it may do little to reduce global emissions. Depending on how

national emission quotas are set, emission trading may simply develop into a giant

scheme to transfer wealth between nations, or - as some have put it - taking from the poor

in the rich countries and giving to the rich in the poor countries.

It is, of course, obvious that oil-exporting nations will suffer economic losses if demand

is reduced by industrialized countries. It is less well known that developing countries,

relying on trade and foreign investments, may also incur losses if the economies of the

industrialized nations falter .

There is considerable concern, particularly in the United States Senate, that imposing

energy restrictions will not only raise energy prices to consumers, but cause industries to

transfer operations to nations that do not incur these restrictions. The current U.S.

administration has attempted to reassure the Congress that economic losses will not occur

or will not be too severe if they do. But if it becomes apparent that a global warming

could produce net benefits rather than net losses, it may be difficult to construct a benefitcost analysis to convince the public and the Congress to go along with restrictions on

energy use through what amounts to a hidden energy tax.

Adapting to Climate Change

The recommended policy to meet any consequences of growing atmospheric greenhouse

gases is to rely on human adaptation to any climate change, coupled with a "no-regrets

policy" of energy conservation and increased energy efficiency. ("No-regrets" energy

policies are those that make economic sense even if no climate change occurs.) Common

sense is the key. Over-conservation can waste energy if it destroys energy-imbedded

capital stock that requires new energy expenditures to replace.

Adaptation has been the traditional method of meeting climate changes; it has worked

over thousands of years for human populations that were not as technologically advanced

nor as materially endowed as those at present. The resources saved by not restricting

energy use through rationing or taxing can be applied to make human societies more

resilient to climate change, whether manmade or natural. After all, any effects from

climate change over the next century will be minor compared to societal changes brought

about by new technology, rising incomes and population growth.

Farming the Ocean

In spite of the absence of observed global warming, and in spite of the expectation that

warm temperatures would likely produce net benefits, governments may still feel

politically compelled to reduce the ongoing increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide. As

an alternative to controlling emissions, the idea of sequestering CO2 from the atmosphere

by creating tree plantations has been widely discussed.

An equivalent scheme - potentially much more effective and with much lower cost than

controlling emissions - would speed up the absorption of excess CO2 into the ocean. It

has been successfully demonstrated recently that fertilizing certain regions of the ocean

with micronutrients, like iron, can significantly increase the populations of

phytoplankton. In addition to enhancing a basic food source for fisheries, ocean farming

can also serve to absorb atmospheric CO2. In short, it may soon be possible to turn

excess CO2 into a resource, making it no longer a menace.