* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The operant behaviorism of BF Skinner

Prosocial behavior wikipedia , lookup

Subfields of psychology wikipedia , lookup

Learning theory (education) wikipedia , lookup

Cross-cultural psychology wikipedia , lookup

Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship wikipedia , lookup

Conservation psychology wikipedia , lookup

Cognitive science wikipedia , lookup

Music psychology wikipedia , lookup

Social psychology wikipedia , lookup

History of psychology wikipedia , lookup

Psychophysics wikipedia , lookup

Experimental psychology wikipedia , lookup

Observational methods in psychology wikipedia , lookup

Symbolic behavior wikipedia , lookup

Insufficient justification wikipedia , lookup

Behavioral modernity wikipedia , lookup

Social perception wikipedia , lookup

Transtheoretical model wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Thin-slicing wikipedia , lookup

Organizational behavior wikipedia , lookup

Attribution (psychology) wikipedia , lookup

Neuroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

Applied behavior analysis wikipedia , lookup

Theory of planned behavior wikipedia , lookup

Sociobiology wikipedia , lookup

Vladimir J. Konečni wikipedia , lookup

Adherence management coaching wikipedia , lookup

Descriptive psychology wikipedia , lookup

Theory of reasoned action wikipedia , lookup

Social cognitive theory wikipedia , lookup

Psychological behaviorism wikipedia , lookup

Behavior analysis of child development wikipedia , lookup

Verbal Behavior wikipedia , lookup

THE BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1984) 7, 473-475

Printed in the United States of America

The operant behaviorism

of B. F. Skinner

A. Charles Catania

Department of Psychology, University of Maryland Baltimore County,

Catonsville, Md. 21228

Of all contemporary psychologists, B. F. Skinner is perhaps the most honored and the most maligned, the most

widely recognized and the most misrepresented, the

most cited and the most misunderstood. Some still say

that he is a stimulus-response psychologist (he is not);

some still say that stimulus-response chains play a central

role in his treatment of verbal behavior (they do not);

some still say that he disavows evolutionary determinants

of behavior (he does not). These and other misconceptions are common and sometimes even appear in psychology texts (e.g. Todd & Morris 1983). How did they come

about, and why do they continue? Although the present

BBS treatments will probably not provide an answer,

they may help to clarify some of the misunderstandings.

The articles sampled here represent a range of Skinner's work (in the treatments, each article is referred to by

its abbreviated title). The first but most recent, "Selection by Consequences " ("Consequences," Skinner 1981),

relates operant theory to other disciplines, and in particular to biology and anthropology. The second, "Methods

and Theories in the Experimental Analysis of Behavior"

("Methods"), outlines some of the basic concepts of operant theory in the context of a discussion of methodological

and theoretical issues; it is an amalgamation of revised

versions of "The Flight from the Laboratory" (Skinner

1961) and "Are Theories of Learning Necessary?" (Skinner 1950) and a portion of the preface to Contingencies of

Reinforcement (Skinner 1969). "The Operational Analysis of Psychological Terms" ("Terms," Skinner 1945) is

the earliest work treated; its special concern is with the

language of private events, and many features of Skinner's analysis of verbal behavior are implicit in it. "An

Operant Analysis of Problem Solving" ("Problem Solving," Skinner 1966a), continues the interpretation of

verbal behavior in distinguishing between rule-governed

and contingency-shaped behavior. "Behaviorism at

Fifty" ("Behaviorism-50," Skinner 1963) addresses the

status of behaviorism as a philosophy of science, and

points out some of the difficulties that must be overcome

by any science of behavior. "The Phylogeny and Ontogeny of Behavior" ("Phylogeny," Skinner 1966b), the

last of the works sampled, considers how evolutionary

variables combine with those operating within an organism's lifetime to determine its behavior.

© 1984 Cambridge University Press

Biography

Burrhus Frederic Skinner was born on March 20,1904, in

Susquehanna, Pennsylvania. After majoring in English at

Hamilton College, he tried a career at writing but gave it

up after finding he had nothing to say. Having a longstanding interest in human and animal behavior and some

familiarity with the writings of Watson, Pavlov, and

Bertrand Russell, he then entered the graduate program

in psychology at Harvard University (Skinner 1976).

There he began a series of experiments that led to more

than two dozen journal articles and culminated in The

Behavior of Organisms (1938). In the manner of The

Integrative Action of the Nervous System (Sherrington

1906) and Behavior of the Lower Organisms (Jennings

1906), the work presented a variety of novel research

findings and provided a context for them. The extensive

data illustrated many properties of reinforcement and

extinction, discrimination and differentiation; the concept of the three-term contingency was to become the

cornerstone for much else that would follow.

In 1936, after three years as a Junior Fellow in the

Harvard Society of Fellows, Skinner moved to the University of Minnesota. His basic research continued, but

during World War II he also worked on animal applications of behavior principles, including the training of

pigeons to guide missiles (Skinner 1960; 1979). Although

the project never got beyond demonstrations, a major

fringe benefit was the discovery of shaping, the technique

for creating novel forms of behavior through the differential reinforcement of successive approximations to a

response.

Another product of those days was the Aircrib, which

Skinner built for his wife and his second daughter (Skinner 1945). It was a windowed space with temperature and

humidity control that improved on the safety and comfort

of the ordinary crib while making the care of the child less

burdensome. It was not used for conditioning the infant

(contrary to rumor, neither of Skinner's daughters developed emotional instability, psychiatric problems or suicidal tendencies). Soon after came the Utopian novel,

Walden Two (1948). Some who later criticized the specifics of that planned society failed to observe that its

experimental character was its most important feature:

0140-525XI84/040473-03I$06.00

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 88.99.165.207, on 16 Jun 2017 at 13:36:43, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00026728

473

Catania: Skinner's behaviorism

Any practice that did not work was to be modified until a

more effective version was found.

In 1945, Skinner assumed the chairmanship of the

Department of Psychology at Indiana University. Then,

after delivering the 1947 William James Lectures at

Harvard University on the topic of verbal behavior, he

returned permanently to the Harvard Department of

Psychology (Skinner 1983). There he completed his book

Verbal Behavior (1957) and, in collaboration with Charles

B. Ferster, developed the subject matter of schedules of

reinforcement (Ferster & Skinner 1957). Much else has

been omitted here (e.g. Science and Human Behavior

[1953] and teaching machines); the articles and books

Skinner has since written are too numerous to list. All but

one of the articles treated ("Terms") are drawn from those

later pieces; they constitute a sample of his most seminal

works. Many others are cited in the course of the treatments.

Operant behaviorism

Operant behaviorism (or radical behaviorism) is the variety of behaviorism particularly identified with Skinner's

work. It provides the systematic context for the research

in psychology sometimes referred to as the experimental

analysis of behavior. Behavior itself is its fundamental

subject matter; behavior is not an indirect means of

studying something else, such as cognition or mind or

brain.

A primary task of an experimental analysis is to identify

classes of behavior on the basis of their origins. Some

classes of responses, respondents, originate with the

stimuli that elicit them (as illustrated by the stimulusresponse relations called reflexes). Others, called operants, are engendered by their effects on the environment;

because they do not require eliciting stimuli, they are

said to be emitted rather than elicited. Admitting the

possibility that behavior could occur without eliciting

stimuli was a critical first step in operant theory. Earlier

treatments had assumed that for every response there

must be a corresponding eliciting stimulus. The rejection

of this assumption did not imply that emitted responses

were uncaused; rather, the point was that there are other

causes of behavior besides eliciting stimuli. Adding operants to respondents as behavior classes did not exhaust

the possibilities, but it was critical to recognize that the

past consequences of responding are significant determinants of behavior.

The consequences of a response may either raise or

lower subsequent responding. Consequences that do so

are respectively called reinforcers and punishers (punishment has sometimes been confused with negative reinforcement, but positive and negative reinforcement both

involve increases in responding; they differ in whether

the consequence of responding is the addition to or

removal of something from the environment, as in the

difference between appetitive procedures and those involving escape or avoidance). The particular reh; tions that

can be established between responses and their consequences are called contingencies of reinforcement or

punishment.

But the consequences of responding are also typically

correlated with other features of the environment (some

474

consequences of stepping on the brake pedal or the gas

pedal, for example, depend on whether the traffic light is

red or green). When a stimulus sets the occasion on which

responding will have a particular consequence, the stimulus is said to be discriminative. If responses then come to

depend on, or come under the control of, this stimulus,

the response class is called a discriminated operant. Both

respondents and discriminated operants involve an antecedent stimulus, but the distinction between them is

crucial and depends on whether consequences of responding play a role. A response that depends only on the

presentation of a stimulus, as in a reflex relation, is a

member of a respondent class. One that depends on the

relations among the three terms - stimulus, response,

consequence — is a member of a discriminated operant

class. Thus, discriminated operants are said to be defined

by a three-term contingency. The three-term contingency is often neglected by those who think of behavior

change only in terms of the instrumental and classical

procedures of earlier conditioning theories.

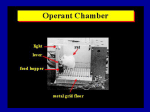

Much of the research that helped to establish this

vocabulary was conducted in the experimental chamber

that for a while was known as the Skinner box (that term

was more often used by those outside than by those

within the experimental analysis of behavior). Simple

stimuli (lights, sounds), simple responses (lever presses,

key pecks), and simple reinforcers (food, water) were

arranged for studying the behavior of rats or pigeons.

Many responses automatically have particular consequences (to see something below eye level, for example,

we look down rather than up). But natural environments

do not ordinarily include levers on which presses produce

food pellets only when lights are on. Operant chambers

were designed to create arbitrary contingencies; they

were arbitrary, but only in this sense. As for responses

such as the pigeon's key peck:

Such responses are not wholly arbitrary. They are

chosen because they can be easily executed, and because they can be repeated quickly and over long

periods of time without fatigue. In such a bird as the

pigeon, pecking has a certain genetic unity; it is a

characteristic bit of behavior which appears with a welldefined topography. (Ferster & Skinner 1957, p. 7)

Given this recognition of genetic determinants in the

specification of operant classes, it is ironic that some

species-specific characteristics of lever presses and key

pecks later became the basis for criticisms of operant

theory. Perhaps these responses were not arbitrary

enough. But given that the concern was to study the

effects of the consequences of responding, it would hardly

have been appropriate to have sought out response classes so highly determined in other species-specific ways

that they would have been insensitive to their consequences.

There are "natural lines of fracture along which behavior and environment actually break" (Skinner 1935, p.

40). "We divide behavior into hard and fast classes and

are then surprised to find that the organism disregards

the boundaries we have set" (Skinner 1953, p. 94). Operant theory is not compromised by demonstrations that

some response classes are more easily established than

others, or that some discriminations can be more easily

established with some reinforcers than with others. Consequences are important, but they do not operate to the

THE BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1984) 7:4

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 88.99.165.207, on 16 Jun 2017 at 13:36:43, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00026728

References /Catania: Skinner's behaviorism

exclusion of other sources of behavior, including phylogenic ones. Phenomena such as autoshaping (producing

a pigeon's pecks on a key by repeatedly lighting the key

and then operating the feeder) were discovered in the

course of operant research, and present no more of a

problem to operant accounts than do the respondent

conditioning phenomena studied by Pavlov.

The discovery that behavior could be maintained easily

even when only an occasional response was reinforced led

to the investigation of schedules of reinforcement. Schedules arrange reinforcers on the basis of the number of

responses, the time at which responses occur, the rate of

responding, or various combinations of these and other

variables. In more complicated cases, different schedules

operate either successively or simultaneously in the presence of different stimuli or for different responses. Reinforcement schedules have proven useful in such areas as

psychopharmacology and behavioral toxicology. The performances generated by complex schedules are also

sometimes analogous to performances that in humans are

discussed in terms of preference, self-control, and so on

(e.g. see "Methods").

In its extension to verbal behavior, a primary task of an

operant analysis is again that of identifying the various

sources of behavior. Its concern is with the functions of

language rather than with its structure. In the tact relation, for example, an object or event is a discriminative

stimulus that sets the occasion for a particular utterance,

as when one says "apple" upon seeing an apple (tacting is

not equivalent to naming or referring to; the relation

called reference involves another class of behavior, called

autoclitic). Through the tact relation, verbal behavior

makes contact with events in the world. Other relations

include (but are not limited to) the intraverbal, in which

verbal behavior serves as a discriminative stimulus for

ather verbal behavior (as in learning addition or multiplication tables), the textual, in which written text provides the discriminative stimuli (as in reading aloud), and

:he mand, in which the verbal response specifies a consequence (as in making a request or asking a question). Any

utterance, however, is likely to involve these and other

relations in combination; verbal behavior is a product of

multiple causation. Novel utterances may be dealt with

by showing how their various components (words,

phrases, grammatical forms) have each been occasioned

by particular aspects of a current situation; novelty, in

other words, comes about through novel combinations of

existing verbal classes.

More important, these elementary relations are only

the raw materials from which verbal behavior is constructed. A sentence cannot exist solely as a combination

of these elementary units. Speakers report on the conditions under which they are behaving verbally (as when

someone says, "I am happy to report that . . ."), they

cancel the effects of their own verbal behavior (as when

they include "not" in a sentence), they indicate its

strength (as when they speak of being sure or uncertain),

and so on. In each of these cases, some parts of the

speaker's verbal behavior are under the discriminative

control of the various other verbal relations. These processes, called autoclitic, are the basis for larger verbal

units (e.g. sentences) and for the complexities of self-

editing, logical verbal behavior, and so on. The nestings

and orderings and coordinations of these processes are

intricate, but they can nevertheless be accommodated by

the discriminative stimuli and the responses and the

consequences of the three-term contingency. This sort of

analysis is illustrated in "Terms"; although that article

predated Skinner's development of the vocabulary of

Verbal Behavior, these relations are implicit in it, and

more is involved in it than simply the tacting of private

events.

These and other aspects of operant behaviorism are

discussed in the treatments that follow. For the commentators, the articles are the stimuli, their commentaries are

the responses, and Skinner's replies are the consequences. For Skinner, the commentaries are the stimuli

and his replies are the responses; some of the consequences will be evident only in the effects of the treatments on their readers. Other potential responses and

consequences produced by these treatments are even

more remote and also remain to be seen. To the extent

that they may correct some misreadings of operant theory, they are steps in the right direction. Given that we

have already taken more than a single step, our journey

has already begun. This is as it should be, because there is

much to explore and the journey will not be short.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Preparation of the introductory and concluding remarks was

supported in part by NSF grant BNS82-03385 to the University

of Maryland Baltimore County. Some passages from the introduction were excerpted from Catania (1980), with permission of

the publisher.

References

Catania, A. C. (1980) Operant theory: Skinner. In: Theories of learning, ed.

G. M. Gazda & R. Corsini. F. E. Peacock.

Ferster, C. B. & Skinner, B. F. (1957) Schedules of reinforcement. AppletonGentury-Crofts.

Jennings, H. S. (1906) Behavior of the lower organisms. Macmillan.

Sherrington, C. (1906) The integrative action of the nervous system.

Scribner's.

Skinner, B. F. (1935) The generic nature of the concepts of stimulus and

response. Journal ofCeneral Psychology 12:40-65.

(1938) The behavior of organisms. Appleton-Ceiitury-Crofts.

(1945) The operational analysis of psychological terms. Psychological Review

42:270-77; 291-94.

(1948) Walden two. Macmillan.

(1950) Are theories of learning necessary? Psychological Review 57:193-216.

(1953) Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

(1957) Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

(1960) Pigeons in a pelican. American Psychologist 15:28-37.

(1961) The flight from the laboratory. In: Current trends in psychological

theory, ed. Wayne Dennis et al. University of Pittsburgh Press.

(1963) Behaviorism at fifty. Science 140:951-58.

(1966a) An operant analysis of problem solving. In: Problem solving:

Research, methods, and theory, ed. B. Kteinmuntz. John Wiley & Sons.

(1966b) Phylogeny and ontogeny of behavior. Science 153:1205-13.

(1969) Contingencies of reinforcement: A theoretical analysis. Prentice-Hall.

(1976) Particulars of my life. Knopf.

(1979) The shaping of a behaciorist. Knopf.

(1981) Selection by consequences. Science 213:501-4.

(1983) A matter of consequences. Knopf.

Todd, J. T. & Morris, E. K. (1983) Misconception and miseducation:

Presentations of radical behaviorism in psychology textbooks. Behavior

Analyst 6:153-60.

THE BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1984) 7:4

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 88.99.165.207, on 16 Jun 2017 at 13:36:43, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00026728

475

Call for Papers

Investigators in

Psychology,

Neuroscience,

Behavioral Biology, and

Cognitive Science

Do you want to:

• draw wide attention to a particularly

important or controversial piece of work?

• solicit reactions, criticism, and feedback

from a large sample of your peers?

• place your ideas in an interdisciplinary,

international context?

The Behavioral

and Brain Sciences B

an extraordinary journal now in its seventh year, provides a

special service called Open Peer Commentary to researchers in any area of psychology, neuroscience,

behavioral biology or cognitive science.

Papers judged appropriate for Commentary are circulated

to a large number of specialists who provide substantive

criticism, interpretation, elaboration, and pertinent complementary and supplementary material from a full crossdisciplinary perspective.

Article and commentaries then appear simultaneously with

the authors formal response. This BBS "treatment"

provides in print the exciting give and take of an international seminar.

The editor of BBS is calling for papers that offer a clear

rationale for Commentary, and also meet high standards of

conceptual rigor, empirical grounding, and clarity of style.

Contributions may be (1) reports and discussions of empirical research of broader scope and implications than might

be reported in a specialty journal; (2) unusually significant

theoretical articles that formally model or systematize a

body of research; and (3) novel interpretations, syntheses or

critiques of existing theoretical work.

Although the BBS Commentary service is primarily devoted

to original unpublished manuscripts, at times it will be extended to precis of recent books or previously published

articles.

Published quarterly by Cambridge University Press. Editorial correspondence to: Stevan Harnad, Editor, BBS,

Suite 240, 20 Nassau Street, Princeton, NJ 08542.

" . . . superbly presented . . . the result is

practically a vade mecum or Who's Who in

each subject. [Articles are] followed by pithy

and often (believe it or not) witty comments

questioning, illuminating, endorsing or just

plain arguing . . . I urge anyone with an interest in psychology, neuroscience, and behavioural biology to get access to this journal."—New Scientist

"Care is taken to ensure that the commentaries

represent a sampling of opinion from scientists

throughout the world. Through open peer commentary, the knowledge imparted by the target

article becomes more fully integrated into the

entire field of the behavioral and brain sciences.

This contrasts with the provincialism of specialized journals . . ."—Eugene Garfield Current

Contents

"The field covered by BBS has often suffered in the past from the drawing of battle

lines between prematurely hardened positions: nature v. nurture, cognitive v. behaviourist, biological v. cultural causation. . . .

[BBS] has often produced important articles

and, of course, fascinating interchanges....

the points of dispute are highlighted if not

always resolved, the styles and positions of

the participants are exposed, hobbyhorses

are sometimes ridden with great vigour, and

mutual incomprehension is occasionally

made very conspicuous . . . . commentaries

are often incisive, integrative or bring highly

relevant new information to bear on the subject."— Nature

" . . . a high standard of contributions and discussion. It should serve as one of the major

stimulants of growth in the cognitive sciences

over the next decade." — Howard Gardner

(Education)

Harvard

" . . . keep on like this and you will be not

merely good, but essential..."—D.O. Hebb

(Psychology)

Dalhousie

" . . . a unique format from which to gain some

appreciation for current topics in the brain sciences . . . [and] by which original hypotheses

may be argued openly and constructively."—

Allen R. Wyler (Neurological Surgery)

Washington

" . . . one of the most distinguished and useful of scientific journals. It is, indeed, that

rarity among scientific periodicals: a creative forum . . ."—Ashley Montagu (Anthropology)

Princeton

"I think the idea is excellent."—Noam Chomsky

(Linguistics)

M.I.T.

" . . . open peer commentary . . . allows the

reader to assess the 'state of the art' quickly

in a particular field. The commentaries provide a 'who's who' as well as the content of

recent research."—Journal of Social and Biological Structures

" . . . presents an imaginative approach to learning which might be adopted by other journals."—Library Journal

"Neurobiologists are acutely aware that

their subject is In an explosive phase of development . . . we frequently wish for a forum for the exchange of ideas and interpretations . . . plenty of journals gladly carry the

facts, very few are willing to even consider

promoting ideas. Perhaps even more important is the need for opportunities publicly to

criticize traditional and developing concepts

and interpretations. [BBS] is helping to fill

these needs."—Graham Hoyle (Biology)

Oregon

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 88.99.165.207, on 16 Jun 2017 at 13:36:43, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00026728