* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Lecture25

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Non-coding DNA wikipedia , lookup

Human genome wikipedia , lookup

Minimal genome wikipedia , lookup

Epigenetics of human development wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression profiling wikipedia , lookup

Nucleic acid tertiary structure wikipedia , lookup

Cre-Lox recombination wikipedia , lookup

Artificial gene synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Epitranscriptome wikipedia , lookup

Pathogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Genome editing wikipedia , lookup

Metagenomics wikipedia , lookup

Genome evolution wikipedia , lookup

Helitron (biology) wikipedia , lookup

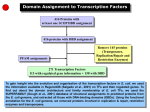

Combined analysis of ChIPchip data and sequence data Harbison et al. CS 466 Saurabh Sinha Outline • Transcription factors interpret the regulatory information encoded in DNA to induce or repress gene expression • Comparative genomics has been used to find the regulatory sites in yeast genome • Looking at sequence alone does not reveal if a putative site is actually functioning as a binding site • ChIP-chip data (also called “location data”) provides such information • Harbison et al combine these two types of data Chip-on-chip Source: http://www.chiponchip.org/ Data • Genome-wide “location analysis” using ChIPon-chip • Each experiment done with one TF • 203 TFs experimented with, in “rich media conditions” • 84 of these TFs also experimented with in at least one other condition • Why? – Binding is not just a function of the presence of the site. It is also a function of the presence of the TF – TF may not be present in every condition Data • How were the 84 TFs (to be tested in additional conditions) chosen? • If there was prior evidence that they play a role in that additional condition ChIP-on-chip results • 11,000 unique interactions between TFs and promoter regions identified • A matrix of (m x n), where m is the number of TFs (203), n is the number of yeast genes (~6000) • 11,000 of the entries were “1”, meaning the binding was significant – Need post-processing of binding affinities to assess if it is statistically significant The next step: bring in the sequence • Genome-wide “location data” or “binding data” combined with sequence data • For each TF, collect all sequences bound by it – These are promoter length sequences, not exact binding sites • Apply motif finding programs to estimate what the binding motif is (where the binding sites are) Motif finding • Only consider TFs that bound >= 10 sequences – 147 such TFs • Run 6 different motif-finders on the bound sequences • 68000 motifs discovered ! • A large number of these motifs are “variants” of the same motif, i.e., similar to each other Motif finding • Using clustering of motifs, and stringent statistical tests, identify high confidence motifs from among these 68000 motifs • High confidence motifs found for 116 of the 147 TFs whose bound sequences were analyzed • Now require that the motif also be conserved across other related yeast species • 65 TFs with single, high-confidence, phylogenetically conserved motifs were found Motif finding • The 65 motifs were a mix of “known” and novel motifs. – That is, some of the motifs were similar to already known motifs – 21 TFs’ motifs were new • Took these 65 motifs, as well as other known motifs from the literature to form a compendium of 102 motifs for further analysis Source: Harbison et al. Nature 431, 99-104(2 September 2004) Next step • We now have motifs for 102 TFs • Next step is to locate binding sites of each TF in the whole genome • Equivalent to finding matches to each motif in the whole genome • Finding matches: – Require a high sequence similarity – Require phylogenetic conservation – Require high binding to that region by TF Mapping sites in the genome • “Map” gave 3353 sites (“interactions”) within 1296 promoters • This is different from simply locating matches to motif • Because TF binding information is also incorporated • Under different conditions, only a subset of the binding sites in the map are actually occupied Source: Harbison et al. Nature 431, 99-104(2 September 2004) Does the map make sense? • The map is telling us which TFs bind which actual sites in the genome, and hence which genes are being regulated • In many cases, the known functions of the genes predicted to be targeted by a TF are consistent with the known function of the TF More insights from the map • Binding sites are not uniformly distributed over the promoter regions • Sharply peaked distribution • Very few sites in 100 bp immediately upstream of the genes • Most sites (74%) are between 100 and 500 bp of gene Source: Harbison et al. Nature 431, 99-104(2 September 2004) Arrangements of sites • Specific arrangements of binding sites in a promoter • Simple arrangement: one binding site for one TF • Another arrangement: Repeats of a particular binding site – Allows for “graded response” – Some TFs show a significant preference for repeated sites Source: Harbison et al. Nature 431, 99-104(2 September 2004) Arrangements of sites • Another arrangement: Binding sites for multiple TFs – “Combinatorial regulation”: In different conditions, different combinations of binding sites (and TFs) direct different gene expression – Genes whose promoters have such arrangement of sites are required for multiple pathways, and regulated in environment-specific fashion Source: Harbison et al. Nature 431, 99-104(2 September 2004) Arrangements of sites • Another arrangement: Binding sites for specific pairs of TFs occur more frequently in same promoter than expected by chance – The two TFs perhaps interact physically in doing their job Source: Harbison et al. Nature 431, 99-104(2 September 2004)