* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Whey Protein: A Functional Food

Paracrine signalling wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression wikipedia , lookup

Biosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

G protein–coupled receptor wikipedia , lookup

Clinical neurochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Genetic code wikipedia , lookup

Amino acid synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Expression vector wikipedia , lookup

Magnesium transporter wikipedia , lookup

Ancestral sequence reconstruction wikipedia , lookup

Biochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Metalloprotein wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation wikipedia , lookup

Lactoferrin wikipedia , lookup

Interactome wikipedia , lookup

Western blot wikipedia , lookup

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of proteins wikipedia , lookup

Protein purification wikipedia , lookup

Protein structure prediction wikipedia , lookup

Protein–protein interaction wikipedia , lookup

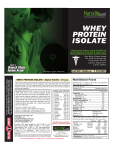

Whey Protein: A Functional Food Carol Bayford, BSc (Hons) Nutritional Therapy Introduction Whey protein, with its high protein quality score and high percentage of BCAAs (branched chain amino acids), has long been popular in the exercise industry as a muscle-building supplement. However, research suggests it may have far wider applications as a functional food in the management of conditions such as cancer, hepatitis B, HIV, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis and even chronic stress. Whey Protein Production Whey protein is extracted from whey, the liquid material created as a by-product of cheese production. Advances in processing technology have resulted in a number of different finished whey products with varying nutritional profiles. These are summarised in Table 1 which is has been 1 extracted from K. Marshall’s ‘Therapeutic Applications of Whey Protein’ . Table 1: Commercially Available Whey Proteins Product Description Protein Concentration Whey Protein Isolate Whey Protein Concentrate • • • 90-95% Hydrolysed Whey Protein • • Variable Hydrolysis used to cleave peptide bonds, creating smaller peptide fractions Reduces allergic potential compared with non-hydrolysed • Undenatured Whey Concentrate • • • The Nutrition Practitioner May range from 25-89% Most commonly available as 80% Variable Usually ranges from 2589% Processed to preserve native protein structures: typically has Fat, Lactose, Mineral Content • Negligible • Some fat / lactose / minerals which decrease as protein concentration increases • Varies with protein concentration • Some fat / lactose / minerals which decrease as protein concentration increases Spring 2010 Whey Protein – A functional food Carol Bayford higher amounts of immunoglobulins and lactoferrin The Nutrition Practitioner Spring 2010 Whey Protein – A functional food Carol Bayford Biological Components Amino Acid Content Whey is made up of a number of proteins including beta-lactoglobulin, alpha-lactalbumin, bovine serum albumin (BSA) and glycomacropeptide (GMP). Collectively, these contain a full spectrum of amino acids including the BCAAs leucine, isoleucine and valine. BCAAs are required for tissue growth 1. and repair and leucine in particular plays a key role in the translation-initiation of protein synthesis The sulphur-containing amino acids cysteine and methionine are also found in high concentrations in whey protein, contributing to enhanced immune function through intracellular conversion to 1 glutathione . Interestingly, GMP – although a source of BCAAs – lacks the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tryptophan and tyrosine. This makes it a viable protein option for individuals with PKU (Phenylketonuria). Lactoferrin 2,3 Lactoferrin is a non-haem iron-binding glycoprotein with antimicrobial and antioxidant effects . Comprising a single polypeptide chain with two binding sites for ferric ions, whey lactoferrin appears to exert its effects by regulating iron absorption.4 Immunoglobulins Immunoglobulins form a significant 10-15% of total whey proteins derived from bovine milk and of 1,5 these, IgG has been found at concentrations of 0.6-0.9 mg/ml . According to the results of an in vitro study, bovine IgG at concentrations as low as 0.3mg/ml suppressed synthesis of human IgG, IgA and IgM by up to 98%. Based on these findings, the study concluded that bovine milk has the potential to modulate immune response in humans5. Other studies have demonstrated that raw milk from nonimmunised cows contains specific antibodies to E. coli, Salmonella enteriditis, S. typhimurium, Shigella flexerni and human rotovirus.6,7 Lactoperoxidase Lactoperoxidase is the most abundant enzyme in whey and has been shown to have anti-bacterial effects across a range of species. Its effects are linked to its ability to reduce hydrogen peroxide, 1,8 catalysing peroxidation of thiocyanate and certain halides (including iodine and bromium) . Lactoperoxidase appears to have the qualities of a stable preservative as it is not inactivated during 1 the pasteurisation process. Mechanism of Action Whey’s antioxidant and detoxifying activity is most likely linked to its contribution to the synthesis of glutathione (GSH). Cysteine (which contains an antioxidant thiol group) combines with glycine and 1 glutamate to form GSH . GSH is the major endogenous antioxidant produced by cells, providing protection for RNA, DNA and proteins via its redox cycling from GSH (the reduced form) to GSSH 9 (the oxidised form) . Through direct conjugation, GSH detoxifies a host of both endogenous and exogenous toxins including toxic metals, petroleum distillates, lipid peroxides, bilirubin and 9 prostaglandins. Lactoferrin’s antioxidant and antimicrobial effects have already been touched on briefly. Due to its ability to chelate iron, organisms requiring this metal to replicate would seem to be particularly vulnerable to lactoferrin’s effects. Lactoferrin also demonstrates an ability to stimulate immune 1,10 responses involving natural killer (NK) cells, neutrophils and macrophage cytotoxicity . Furthermore, a mouse study concluded that lactoferrin acts as an anti-inflammatory by regulating 11 levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin 6 (IL-6). The protein beta-lactoglobulin contains anti-hypertensive peptides which act as significant 12 angiotensin 1 converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors . Cholesterol-lowering effects have also been noted 1 as a result of changes in micellar cholesterol solubility in the intestine. The Nutrition Practitioner Spring 2010 Whey Protein – A functional food Carol Bayford Absorption Whey proteins are considered to be ‘fast proteins’ in that they reach the jejunum quickly after entering the gastrointestinal tract. Once in the small intestine (SI), whey undergoes slow hydrolysis which 1 encourages greater absorption over the length of the SI . This superior absorption makes whey an ideal optional source of vital protein for those with compromised GI function, such as ileostomy 1 patients . It is speculated that cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy may also benefit, as anti13 cancer therapies influence nutrient intake and absorption. Clinical Indications Cancer A number of animal studies have examined whey’s anticancer potential, believed to derive largely 1 from the antioxidant, detoxifying and immune enhancing effects of GSH and lactoferrin. In the 14 presence of lactoferrin, colon cancer induced in rats showed reduced tumour expression while 15 metastasis of primary tumours in mice was inhibited . Results of an in vitro study have also been encouraging, demonstrating inhibition of growth in human breast cancer cells when treated with the 16 protein BSA. A small number of clinical trials have been undertaken, proposing that high levels of GSH in tumour 1 cells confer resistance to chemotherapeutic agents . Of these, one study of 5 patients produced 17 conflicting results, highlighting the need for larger trials . In another, 20 patients with stage IV malignancies were treated daily with 40g whey in combination with supplements such as ascorbic acid and a multi-vitamin/mineral formulation18. Six months later the 16 survivors demonstrated increased levels of NK cell function, GSH, haemoglobin and haematocrit. Unfortunately the study did not include a comparison with whey alone. Whey may also have a role to play as part of an integrated approach which combines nutrition, exercise and hormonal support to counteract the muscle-wasting frequently associated with cancer. Professor Vickie Baracos explores the feasibility of using this sports medicine model in her article 19 ‘New Approaches in Reversing Cancer-related Weight Loss’ . She highlights that this combination has already been adopted by researchers exploring muscle wasting in other groups: the elderly, patients with wasting syndromes associated with AIDS and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Hepatitis B Although an initial in vitro study found that bovine lactoferrin prevented hepatitis C virus (HCV) in a 20 human hepatocyte line , subsequent trials have proved inconclusive. However, results for hepatitis B virus (HBV) have been more positive, particularly an open study on 8 patients taking 12g of whey daily. Subjects demonstrated improved liver function markers, decreased serum lipid peroxidase 21 levels and increased IL-2 and NK activity. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) 1 Individuals with HIV commonly have low levels of GSH . Several studies have sought to address this by testing the effect of whey protein on the GSH levels of HIV-positive subjects. In one instance, 18 participants were randomised to receive daily doses of 45g whey protein from two different products 22 over a six month period . Only one of the products significantly elevated GSH levels (Protectamin®, manufactured by Fresenius Kabi, Germany), a result that may be related to production at differing isolation temperatures and non-comparable amino acid profiles. Cardiovascular Disease According to the results of a number of studies, milk intake and milk products can lower blood 1 pressure and reduce the risk of hypertension . In one particular eight week trial, 20 healthy men were The Nutrition Practitioner Spring 2010 Whey Protein – A functional food Carol Bayford given a combination of fermented milk and whey protein concentrate to establish whether serum 23 lipids and blood pressure would be affected . The placebo group received only unfermented milk. After eight weeks, the fermented milk group demonstrated comparatively higher HDLs, lower triglycerides and reduced systolic blood pressure. The effect of whey alone was not studied. Osteoporosis Milk basic protein (MBP) is a component of whey which demonstrates the ability to not only suppress 1 bone resorption, but also to stimulate proliferation and differentiation of osteoblastic cells . MBP contains largely lactoferrin and lactoperoxidase. Animal studies suggest that lactoferrin may be the key active component, mediating its effects through two main pathways: LRP1 (a low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein which endocytoses lactoferrin into the cytoplasm of primary 24 osteoblasts) and p42/44 MAPK (which stimulates osteoblast activity) . A number of clinical trials support MBP’s positive effects in both men and women, the latter ranging in age from young to post25, 26,27 menopausal . Daily doses of MBP 40mg (equivalent to 400-800 mL of milk) appear to be sufficient to produce significantly increased bone mineral density and reduced bone resorption. Stress Adaptation Whey enriched with the protein alpha-lactalbumin has been shown to improve cognitive performance 28,29 and mood in stress-vulnerable subjects . Alpha-lactalbumin is particularly high in tryptophan and the authors propose that this acts as a substrate to increase serotonin levels which may be vulnerable to depletion by chronic stress. After the studies, subjects all showed higher ratios of plasma TrpLNAA (the ratio of plasma tryptophan to the sum of the other large neutral amino acids), believed to be an indirect indication of brain serotonin function. Gastrointestinal Support Whey is used as a gastrointestinal supporter by health professions such as Nutritional Therapy Practitioners. Its mucosa-protective effects are well-proven by several animal studies and are likely to 1 be associated with its GSH-stimulating properties . In addition to its role in GSH synthesis, the amino acid glutamate may play a further role when it is converted to glutamine, an amino acid utilised as a 30,31 fuel by intestinal mucosa Choosing the Right Whey Product Given the variety of different whey products available, it is possible to select products for specific clinical indications. For athletes or those looking for a highly-absorbable, low allergenicity protein source, hydrolysed whey – with its readily available di- and tri-peptides - may be a good option. For the immune-compromised or microbe-challenged, undenatured whey’s high levels of lactoferrin and immunoglobulins may be helpful. Comparison of Whey with Pea and Soy Protein Powders Despite no serious adverse reactions to whey powders having been reported, they may not be suitable 1 for those with frank milk allergies . That said, it is worth noting that casein – which is not a component of whey - is often the culprit for dairy-sensitive individuals. Although most whey proteins are processed to remove all but trace amounts of lactose, for the lactose-intolerant, a de-lactosed whey may be a more sensible option. Prior to using therapeutic quantities, a challenge test with a small 1 amount of the proposed whey product would certainly be advisable for those with dairy sensitivities. Non-dairy protein powders are an alternative for individuals with dairy issues, including vegans. Table 2 below compares the amino acid profile of specific whey, pea and soy protein powders and highlights possible clinical indications for each. Table 2: Comparison of Whey, Pea and Soy Protein Powders Amino Acids The Nutrition Practitioner Whey32 Pea33 Soy34 Spring 2010 Whey Protein – A functional food (*=Essential) Alanine Arginine Aspartic Acid Cysteine Glutamic Acid Glycine Histidine Isoleucine (BCAA)* Leucine (BCAA)* Lysine* Methionine* Phenylalanine* Proline Serine Threonine* Tryptophan* Tyrosine Valine (BCAA)* (Metagenics ‘Perfect Protein’ – microfiltered isolate) g/100g 4.00 1.43 8.78 1.83 13.57 1.43 1.30 4.70 8.09 6.87 1.74 2.30 4.26 3.52 5.35 1.43 2.35 4.48 A comprehensive functional food which supplies key proteins such as lactoferrin and immunoglobulins in addition to amino acids. Carol Bayford (Kirkman Pea Protein Powder) g/100g 5.04 8.71 12.43 0.76 13.74 4.64 2.52 5.59 8.44 6.82 1.31 6.13 5.29 4.80 4.34 1.06 3.12 5.27 Ideal for vegetarians and/or individuals with sensitivity issues. (NutraBio Soy Protein Isolate) g/100g 3.80 6.70 10.20 1.10 16.80 3.70 2.30 4.30 7.20 5.60 1.10 4.60 4.50 4.60 3.30 1.20 3.30 4.40 Suitable for vegetarians and those with sensitivity issues, although soy may be a problem for some. A source of isoflavones which may have possible positive effects on heart disease, menopausal symptoms, osteoporosis and breast/prostate cancers The relatively high levels of arginine in both pea and soy protein powders may stimulate the onset of Herpes simplex in susceptible individuals, as this 35 amino acid is essential for replication of the virus Conclusion Whey protein is a complex functional food which reflects its wide range of potential therapeutic applications. The variety of available products allows for a tailored clinical approach although caution is advised if dairy sensitivity is suspected. In these cases, non-dairy options such as pea or soy protein powders may be viable alternatives. About the Author Carol Murrell is a qualified nutritional therapist who trained at the Centre for Nutrition & Lifestyle Management (CNELM) in Wokingham. A keen runner and cyclist, her areas of special interest include sports nutrition from a nutritional therapy perspective, women’s health and cancer care. She is also a qualified NLP (Neuro Linguistic Programming) practitioner and uses these powerful techniques to help individuals effect change in their lives. Carol is a Professional Member of the South African Association of Nutritional The Nutrition Practitioner Spring 2010 Whey Protein – A functional food Carol Bayford References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Marshall, K., 2004. Therapeutic Applications of Whey. Alternative Medicine Review, 9 (2): 136-156 Caccavo, D., 2002. Review: Antimicrobial and immunoregulatory functions of lactoferrin and its potential therapeutic application. Journal of Endotoxin Research, 8 (6): 403-417 Gutteridge, J.M.C, Paterson, S.K., Segal, A.W. et al., 1981. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation by the iron-binding protein lactoferrin. Biochem J., 199 (1): 259-261 Nemet, K., Simonovits, I., 1985. The biological role of lactoferrin. Haematologica (Budap)., 18 (1): 3-12 Kulczycki, A., Macdermott, R.P., 1985. Bovine IgG and Human Immune responses: Con A-Induced Mitogenesis of Human Mononuclear Cells is Suppressed by Bovine IgG. Int.l Arch. Allergy and Immunology, 77 (1-2) : 255-258 Losso, J.N., Dhar, J., Kummer, A. et al., 1993. Detection of antibody specificity of raw bovine and human milk to bacterial lipopolysaccharides using PCFIA. Food and Agricultural Immunology, 5 (4): 231-239 Yolken, R.H., Losonsky, G.A., Vonderfecht, S. et al., 1985. Antibody to human rotovirus in cow’s milk. The New England Journal of Medicine, 312 (10): 605-610 Bjorck, L., 1978. Antibacterial effect of the lactoperoxidase system on psychrophic bacteria in milk. Journal of Dairy Research, 45: (109-118) Bland, J.S., Costarella, L., Levin, B. et al. (2004). Clinical Nutrition – A Functional Approach. 2nd ed. Gig Harbour: The Institute for Functional Medicine Gahr, M., Speer, C.P., Damerau, B. et al., 1991. Influence of lactoferrin on the function of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 49(5): 427-433 Machnicki, M., Zimecki, M., Zagulski, T., 1993. Lactoferrin regulates the release of tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 6 in vivo. Int J Exp Pathol., 74(5): 433-439 Pihlanto-Leppala, A., Koskinen, P., Piilola, K. et al., 2000. Angiotensin 1-converting enzyme inhibitory properties of whey protein digests : concentration and characterisation of active peptides. Journal of Dairy Research, 67: 5364 Lindsey, A.M., 2005. Cancer cachexia: Effects of the disease and its treatment. Nutrition and Cancer, 2 (1): 19-29 Kazunori, S., Watanabe, E., Nakamura, J. et al., 1997. Inhibition of Azoxymethane-initiated Colon Tumour by Bovine Lactoferrin Administration in F344 Rats. Cancer Science, 88 (6): 523-526 Yoo, Y.C., Watanabe, S., Watanabe, R., et al., 1998. Bovine lactoferrin and Lactoferricin inhibit tumour metastasis in mice. Adv Exp Med Biol., 443: 285-91 Laursen, I., Briand, P., Lykkesfeldt, A.E., 1990. Serum albumin as a modulator on growth of the human breast cancer cell line, MCF-7. Anticancer Res., 10 (2A): 343-51 Kennedy, R.S., Konok, G., Bounous, G., et al., 1995. The Use of Whey Protein Concentrate in the Treatment of Patients with Metastatic Carcinoma : A Phase I-III Clinical Study. Anticancer Res., 15: 2643-2650 See, D., Mason, S., Roshan, R., 2002. Increased Tumour Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNT-α) And Natural Killer Cell (NK) Function Using An Integrative Approach In Late Stage Cancers. Immunological Investigations, 31 (2): 137153 Baracos, V.E., 2004. New Approaches in Reversing Cancer-related Weight Loss. Oncology Issues, 9 (2): 5-10 Ikeda, M., Sugiyama, K., Tanaka, T. et al., 1998. Lactoferrin Markedly Inhibits Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Cultured Human Hepatocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communication, 245 (2): 549-553 Watanabe, A., Okada, K., Shimizu, Y. et al., 2000. Nutritional therapy of chronic hepatitis by whey protein (nonheated). J Med., 31 (5-6): 283-302 Micke, P., Beeh, K.M., Buhl, R., 2002. Effects of long-term supplementation with whey proteins on plasma glutathione levels of HIV-infected patients. European Journal of Nutrition, 41 (1): 12-18 Kawase, M., Hashimoto, H., Hosoda, M. et al., 2000. Effect of Administration of Fermented Milk Containing Whey Protein Concentrate to Rats and Healthy Men on Serum Lipids and Blood Pressure. Journal of Dairy Science,83 (2): 255-263 Naot, D., Grey, A., Reid, I.R. ert al., 2005. Lactoferrin – a Novel Bone Growth Factor. Clin Med Res., 3 (2): 93101 Toba, Y., Takada, Y., Matsuoka, Y. et al., 2001. Milk Basic Protein Promotes Bone Formation and Suppresses Bone Resorption in Healthy Adult Men. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 65 (6): 1353-1357 The Nutrition Practitioner Spring 2010 Whey Protein – A functional food 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. Carol Bayford Uenishi, K., Ishida, H., Toba, Y. et al., 2007. Effect of milk basic protein on bone metabolism in healthy young women. Osteoporosis International, 18 (3): 385-390 Aoe, S., Koyama, T., Toba, Y. et al., 2005. A controlled trial of the effect of milk basic protein (MBP) supplementation on bone metabolism in healthy menopausal women, 16 (12): 2123-2128 Markus, C., R., Olivier, B., de Haan, E., 2002. Whey protein rich in alpha-lactalbumin increases the ratio of plasma tryptophan to the sum of the other large neural amino acids and improves cognitive performance in stress-vulnerable subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 75 (6): 1051-1056 Markus, C.,R., Olivier, B., Panhuysen, G.E.M. et al., 2000. The bovine protein alpha-lactalbumin increases the plasma ratio of tryptophan to the other large neural amino acids, and in vulnerable subjects raises brain serotonin activity, reduces cortisol concentration and improves mood under stress. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 71 (6): 1536-1544 Braverman, E.R. (1987). The Healing Nutrients Within. 3rd Ed. Laguna Beach: Basic Health Publications, Inc. O’Dwyer, T., 1989. Maintenance of Small Bowel Mucosa with Glutamine-Enriched Parenteral Nutrition. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 13 (6): 579-585 Metagenics Practitioner Range Catalogue Kirkman. Pea Protein Powder. Available from: www.kirkmanlabs.com/ViewProduct [Accessed 9 March 2010] NutraBio.com. Soy Protein Isolate (Supro). Available from : www.nutrabio.com/Products [Accessed 28 March 2010] Becker, Y., Olshevsky, U., Levitt, J., 1967. The Role of Arginine in the Replication of Herpes Simplex Virus. J Gen Virol., 1: 471-478 The Nutrition Practitioner Spring 2010