* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download File

Third Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Kingdom of Jerusalem wikipedia , lookup

Rhineland massacres wikipedia , lookup

Savoyard crusade wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Nicopolis wikipedia , lookup

Albigensian Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Despenser's Crusade wikipedia , lookup

History of Jerusalem during the Kingdom of Jerusalem wikipedia , lookup

Fourth Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Siege of Acre (1291) wikipedia , lookup

Second Crusade wikipedia , lookup

First Crusade wikipedia , lookup

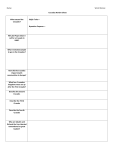

CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Lesson Title: The Crusades Unit Central Historical Question(s): What roll did the Catholic Church play in the Middle Ages? Subject / Course: Social Science Grade: 7 Lesson Duration: (80-90 min) Block schedule Date: What made up the Crusades in Medieval Europe? Lesson Objective, Historical Thinking Skill, as well as California Content & Common Core Standards Lesson Objective: After completing the lesson students will be able to create a timeline of the four main Crusades. Historical Think Skill: Periodization: students will learn about the beginning of the crusades and events throughout the crusades. The students from this lesson will be able to understand the period of the crusades from the beginning to the end. Information will be presented through a PowerPoint and additional sources. Content Standards – 6. Discuss the causes and course of the religious Crusades and their effects on the Christian, Muslim, and Jewish populations in Europe, with emphasis on the increasing contact by Europeans with cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean world. 7.6. Common Core – Language Grade 7 – 3. Use knowledge of language and its conventions when writing, speaking, reading, or listening. a. Choose language that expresses ideas precisely and concisely, recognizing and eliminating wordiness and redundancy.* Reading grade 6-8: 2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions. Narrative Summary of Tasks / Actions For the anticipatory set students will be introduced to the word Crusade and be asked to define what a crusade is and write a short response if there is anything they would crusade for. After I will ask is students want to share their response. For the input I will present a PowerPoint lecture on the Crusades. Students will take notes during the lecture and will be discussing information presented throughout the lecture. For the activity students will break up into groups of four. In the groups the students will examine a source on the crusades and also view examples of what a recruitment poster. After the students will work with their groups and create a recruitment poster for the crusades. Students will present their posters to the class in the form of an art show with one student from each group describing their poster to the class. For assessment students will use their notes, sources, and textbook and create a timeline for the four crusades gone over in class. Students will give a brief description and label key events. For closure the class will have a discussion to wrap up the lesson. I will also ask the students at random to share one thing they have learned from the lesson today. For homework the students will research one of the four crusades presenting the lesson. The students will write a brief description of the crusade they choose. CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Materials / Equipment Computer PowerPoint Whiteboard Poster Board Markers Scissors Handouts with sources (found at end of lesson plan) Textbook Inquiry-Based Lesson Plan for History-Social Science 1. Anticipatory Set Time:10-15min For the anticipatory I will write the word Crusade on the whiteboard. After I write the word I will ask a student to share with the class what the word is and give their definition of what a crusade is. I will also ask additional students to share what their definition of the word is. After the discussion, I will give the students the official definition in which they will be instructed to write down in their notes. Next, I will ask the students to write, on a separate piece of paper, what they would crusade for and why. After I will ask students to share their responses to the class and then introduce the topic of the lesson, the Crusades in Medieval Europe. 2. Central Historical Question Time: What made up the Crusades in Medieval Europe? 3. Teacher Input (delivery of historical context) Time:30-40 For the input of the lesson I will begin by asking the students to take out their notebooks. I will be presenting a short PowerPoint lecture. The power point will consist of information on what the crusades were and provide information on some of the different crusades. Throughout this lecture I will ask my students to take notes, and also prompt them on key items they should take notes on. Throughout the lecture I will be checking for understanding of the key aspects through discussion. I will also answer any questions the students may have regarding the information presented. 4. Student Activity and Investigation (w/ differentiation) Time:25-30min CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template For the activity, I will hand out source material, titled “The Crusades” (historyworld.org) and have the students spilt into pairs. In their pairs the will read and discuss the source material. While they are reading they are to looks for answers and discuss certain key facts. What were the first, second, third, and fourth crusades? Who was involved in each crusade? Where did they take place? Were these the only crusades? After they have finished reading and discussing with their partner the will meet up with another pair and further discussion the source material and questions. Differentiation: For differentiation students will be given the opportunity to read the source electronically on a computer or tablet and have a vocabulary word back to assist with important terms in the source. If needed an alternative source will be made available to fit the students reading level. Extension: Students who finish early will be allowed to use the computer in class to watch videos on the crusades, on websites I give the students to look at (BrainPop, BBC, etc) 5. Lesson Assessment (w/ differentiation) Time:15min For the assessment activity of the lesson I will have the students break from their groups and go back to their normal seats. Once back in their normal seat, I will inform the students that by using their notes, source material, and textbook they are to create a timeline of the four crusades (listing the dates of each) and give a brief description of the causes and events. I will use this assessment to look and see if the students have developed an understanding of the information presented in the lesson and have gained an understanding of what the crusades and the causes were. Differentiation: For differentiation a timeline handout with fill in the blanks will be given to the students who need assistance. Extension: Students who finish early will be allowed to use the computer in class to research material on the crusades as will as watch videos on the crusades on websites I give the students to look at. 6. Closure Time:5-7min For the closer to the lesson, I will bring the class together and ask the students, at random, to share one thing they learned from today’s lesson. I will also allow students to ask any questions regarding the material. If I sense that they have not quite grasped an understanding of the material, I will again review the key aspects of the lesson. I will use the student’s responses in the closure activity to wrap up the lesson and ensure that the students have learned the content intended for them in the lesson. 7. Student Reflection (metacognition) Time:Homework CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template For homework I will hand out an additional source on the crusades and various different recruitment posters. The students will be instructed to look over the sources and images in the packets. Each student will develop a recruitment poster for the crusades. At the bottom of the poster the student shall include a brief description of what they are trying to say with their poster. At the beginning of the next class, I will have the students put their posters up around the classroom. Students will be given an opportunity to walk around and view the posters and descriptions. From this student reflection activity students will think about and analyze how Europe responded to a call for a crusade. By having the students think about and create a poster that they believe would serve to rally the people of Medieval Europe for a crusade. CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template PowerPoint CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Handout Source Material The Crusades In 1095 an assembly of churchmen called by Pope Urban II met at Clermont, France. Messengers from the Byzantine Emperor Alexius Comnenus had urged the pope to send help against the armies of Muslim Turks. On November 27 the pope addressed the assembly and asked the warriors of Europe to liberate the Holy Land from the Muslims. The response of the assembly was overwhelmingly favorable. Thus was launched the first and most successful of at least eight crusades against the Muslim caliphates of the Near East. "God wills it!" That was the battle cry of the thousands of Christians who joined crusades to free the Holy Land from the Muslims. From 1096 to 1270 there were eight major crusades and two children's crusades, both in the year 1212. Only the First and Third Crusades were successful. In the long history of the Crusades, thousands of knights, soldiers, merchants, and peasants lost their lives on the march or in battle. 1095: Beginning of the Crusades In 1095 an assembly of churchmen called by Pope Urban II met at Clermont, France. Messengers from the Byzantine Emperor Alexius Comnenus had urged the pope to send help against the armies of Muslim Turks. On November 27 the pope addressed the assembly and asked the warriors of Europe to liberate the Holy Land from the Muslims. The response of the assembly was overwhelmingly favorable. Thus was launched the first and most successful of at least eight crusades against the Muslim caliphates of the Near East. The word "crusade" literally means "going to the Cross." Hence the idea at the time was to urge Christian warriors to go to Palestine and free Jerusalem and other holy places from Muslim domination. The first crusade was a grand success for the Christian armies; Jerusalem and other cities fell to the knights. The second crusade, however, ended in humiliation in 1148, when the armies of France and Germany failed to take Damascus. The third ended in 1192 in a compromise between English king Richard the Lion-Hearted of England and the Muslim leader Saladin, who granted access to Christians to the holy places. The fourth crusade led to the sacking of Constantinople, where a Latin Kingdom of Byzantium was set up in 1204 and lasted for about 60 years. The Children's Crusade of 1212 ended with thousands of children being sold into slavery, lost, or killed. Other less disastrous but equally futile CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template crusades occurred until nearly the end of the 13th century. The last Latin outpost in the Muslim world fell in 1291. Historians have viewed the Crusades as a mixture of benefits and horrors. On one hand, there was a new knowledge of the East and the possibilities of trade to be found there, not to mention the spread of Christianity. On the other hand, Christianity was spread in a violent, militaristic manner, and the result was that new areas of possible trade turned into new areas of conquest and bloodshed. A number of nonChristians lost their lives to Christian armies in this era, and this trend would continue in the inquisitions of the coming centuries. The Crusades were a series of wars by Western European Christians to recapture the Holy Land from the Muslims. The Crusades began in 1095 and ended in the mid- or late 13th century. The term Crusade was originally applied solely to European efforts to retake from the Muslims the city of Jerusalem, which was sacred to Christians as the site of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. It was later used to designate any military effort by Europeans against non-Christians. The Crusaders carved out feudal states in the Near East. Thus the Crusades are an important early part of the story of European expansion and colonialism. They mark the first time Western Christendom undertook a military initiative far from home, the first time significant numbers left to carry their culture and religion abroad. In addition to the campaigns in the East, the Crusading movement includes other wars against Muslims, pagans, and dissident Christians and the general expansion of Christian Europe. In a broad sense the Crusades were an expression of militant Christianity and European expansion. They combined religious interests with secular and military enterprises. Christians learned to live in different cultures, which they learned and absorbed; they also imposed something of their own characteristics on these cultures. The Crusades strongly affected the imagination and aspirations of people at the time, and to this day they are among the most famous chapters of medieval history. ORIGINS OF THE CRUSADES After the death of Charlemagne, king of the Franks, in 814 and the subsequent collapse of his empire, Christian Europe was under attack and on the defensive. Magyars, nomadic people from Asia, pillaged eastern and central Europe until the 10th century. Beginning about 800, several centuries of Viking raids disrupted life in northern Europe and even threatened Mediterranean cities. But the greatest threat came from the forces of Islam, militant and victorious in the centuries following the death of their leader, Muhammad, in 632. By the 8th century, Islamic forces had conquered North Africa, the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, and most of Spain. Islamic armies established bases in Italy, greatly reduced the size and power of the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire) and besieged its capital, Constantinople. The Byzantine Empire, which had preserved much of the classical civilization of the Greeks and had defended the eastern Mediterranean from assaults from all sides, was barely able to hold off the enemy. Islam posed the threat of a rival culture and religion, which neither the Vikings nor the Magyars had done. In the 11th century the balance of power began to swing toward the West. The church became more centralized and stronger from a reform movement to end the practice whereby kings installed important clergy, such as bishops, in office. Thus for the first time in many years, the popes were able to effectively unite European popular support behind them, a factor that contributed greatly to the popular appeal of the first Crusades. Furthermore, Europe’s population was growing, its urban life was beginning to revive, and both long distance and local trade were gradually increasing. European human and economic resources could now support new enterprises on the scale of the Crusades. A growing population and more surplus wealth also meant greater CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template demand for goods from elsewhere. European traders had always looked to the Mediterranean; now they sought greater control of the goods, routes, and profits. Thus worldly interests coincided with religious feelings about the Holy Land and the pope’s newfound ability to mobilize and focus a great enterprise. FIRST CRUSADE It was against this background that Pope Urban II, in a speech at Clermont in France in November 1095, called for a great Christian expedition to free Jerusalem from the Seljuk Turks, a new Muslim power that had recently begun actively harassing peaceful Christian pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem. The pope was spurred by his position as the spiritual head of Western Europe, by the temporary absence of strong rulers in Germany (the Holy Roman Empire) or France who could either oppose or take over the effort, and by a call for help from the Byzantine emperor, Alexius I. These various factors were genuine causes, and at the same time, useful justifications for the pope’s call for a Crusade. In any case, Urban’s speech—well reported in several chronicles—appealed to thousands of people of all classes. It was the right message at the right time. The First Crusade was successful in its explicit aim of freeing Jerusalem. It also established a Western Christian military presence in the Near East that lasted for almost 200 years. The Crusaders called this area Outremer, French for "beyond the seas." The First Crusade was the wonder of its day. It attracted no European kings and few major nobles, drawing mainly lesser barons and their followers. They came primarily from the lands of French culture and language, which is why Westerners in Outremer were referred to as Franks. The Crusaders faced many obstacles. They had no obvious or widely accepted leader, no consensus about relations with the churchmen who went with them, no definition of the pope’s role, and no agreement with the Byzantine emperor on whether they were his allies, servants, rivals, or perhaps enemies. These uncertainties divided the Crusaders into factions that did not always get along well with one another. Different leaders followed different routes to Constantinople, where they were all to meet. The contingents of Robert of Flanders and Bohemond of Taranto went by sea via Italy, while the other major groups, those of Godfrey of Bouillon and Raymond of Toulouse, took the land route around the Adriatic Sea. As the Crusaders marched east, they were joined by thousands of men and even women, ranging from petty knights and their families, to peasants seeking freedom from their ties to the manor. A vast miscellany of people with all sorts of motives and contributions joined the march. They followed local lords or well-known nobles or drifted eastward on their own, walking to a port town and then sailing to Constantinople. Few knew what to expect. They knew little about the Byzantine Empire or its religion, Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Few Crusaders understood or had much sympathy for the Eastern Orthodox religion, which did not recognize the pope, used the Greek language rather than Latin, and had very different forms of art and architecture. They knew even less about Islam or Muslim life. For some the First Crusade became an excuse to unleash savage attacks in the name of Christianity on Jewish communities along the Rhine. The leaders met at Constantinople and chose to cross on foot the inhospitable and dangerous landscape of what is now Turkey, rather than going by sea. Somehow, despite this questionable decision, the original forces of perhaps 25,000 to 30,000 still survived in sufficient numbers to overcome the Muslim states and principalities of what are now Syria, Lebanon, and Israel. Like Western Christendom, Islam was disunited. Its rulers failed to anticipate the effectiveness of the enemy. In addition, the Franks, as the attacking force, had at least a temporary advantage. They exploited this, taking the key city of Antioch in June 1098, under the lead of Bohemond of Taranto. Then, despite their divisions and factionalism, they moved on to Jerusalem. The siege of Jerusalem culminated in a bloody and destructive Christian victory in CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template July 1099, in which many of the inhabitants were massacred. With victory came new problems. Many Crusaders saw the taking of Jerusalem as the goal; they were ready to go home. Others, especially minor nobles and younger sons of powerful noble families, saw the next step as the creation of a permanent Christian presence in the Holy Land. They looked to build feudal states like those of the West. They hoped to transplant their military culture and to carve out fortunes on the new frontier. Though the Crusaders were more intolerant than understanding of Eastern life, they recognized its riches. They also saw such states as the way to protect the routes to the Holy Land and its Christian sites. The result was the establishment of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, first under Godfrey of Bouillon, who took the title of Defender of the Holy Sepulchre, and then under his brother Baldwin, who ruled as king. In addition to the Latin Kingdom, which was centered on Jerusalem, three other Crusader states were founded: the County of Tripoli, in modern Lebanon; the Principality of Antioch, in modern Syria; and the County of Edessa, in modern northern Syria and southern Turkey. CRUSADES OF THE 12TH CENTURY The Crusades of the 12th century, through the end of the Third Crusade in 1192, illustrate the tensions and problems that plagued the enterprise as a whole. For the lords of Outremer a compromise with the residents and Muslim powers made sense; they could not live in constant warfare. And yet as European transplants they depended on soldiers and resources from the West, which were usually only forthcoming in times of open conflict. Furthermore, rivalries at home were translated into factional quarrels in Outremer that limited any common policy among the states. Nor was the situation helped by the arrival of European princes and their followers, as happened when the Second and Third Crusades came East; European tensions and jealousies proved just as divisive in the East as they had been at home. There is little reason to think that colonization had been anticipated or encouraged by the pope, let alone by the Byzantine emperor; however, it seems a logical consequence of the Crusade’s success. Frankish nobles maintained links with their families at home, and they built lives and careers that spanned the Mediterranean. Moreover, in town and countryside, daily life in the region did not alter greatly; one military master was much like another. Christian lords had no plan for mass conversion of the natives or for any systematic mistreatment comparable to modern genocide or enforced migration. They wanted to maintain their privileged position and to enjoy the lives of European nobles in a new setting. As they settled in, they gradually lost interest in any papal efforts at raising new military expeditions. Nor did they ever reach any real compromise with the Byzantine emperor regarding reconquered territory that had once been his. Although the two groups of Christians had a common enemy, this was not a sufficient motive for cooperation between worlds with so little mutual regard. To the rulers of Muslim states a concerted military effort was imperative. The Franks were an affront to religious as well as to political and economic interests. The combination of zeal and luck that had enabled the Crusaders to triumph in 1099 evaporated in the face of such realities as the need to recruit and maintain soldiers who were loyal and effective. Islamic rulers turned almost at once to the offensive, though a major blow to Christian power did not come until 1144, when the Muslims recaptured Edessa, on the Euphrates River. The city of Edessa had guarded the back door of the Frankish holdings, which were mostly near the coast. This loss marked the beginning of the end of a viable Christian military bastion against Islam. News of the fall of Edessa reverberated throughout Europe, and the Second Crusade was called by Pope Eugenius III. Though the enthusiasm of 1095 was never again matched, a number of major figures joined the Second Crusade, including Holy Roman Emperor Conrad III and France’s King Louis VII. Conrad made the mistake of choosing the land route from Constantinople to the Holy Land and his army was decimated at Dorylaeum in Asia Minor. The French army was more fortunate, but it CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template also suffered serious casualties during the journey, and only part of the original force reached Jerusalem in 1148. In consultation with King Baldwin III of Jerusalem and his nobles, the Crusaders decided to attack Damascus in July. The expedition failed to take the city, and shortly after the collapse of this attack, the French king and the remains of his army returned home. The Second Crusade resulted in many Western casualties and no gains of value in Outremer. In fact the only military gains during this period were made in what is now Portugal, where English troops, which had turned aside from the Second Crusade, helped free the city of Lisbon from the Moors. After the failure of the Second Crusade, it was not easy to see where future developments would lead. In the 1120s and 1130s the Military Religious Orders had been created to further the Crusading ideal by combining spirituality with the martial ideas of knighthood and chivalry. Men who joined the orders took vows of chastity and obedience patterned after those of monasticism. At the same time they were professional soldiers, willing to spend long periods in the East. The most famous were the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, called Hospitalers, and the Poor Knights of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, called Templars. These groups sent men to Outremer to protect Christian pilgrims and settlements in the east. This meant that the rulers in Outremer did not have to depend only on the huge but wayward armies led by princes. These orders of Crusading knights tried to mediate between the Church’s concerns and the more worldly interests of princes who saw the East as an extension of their own ambitions and dynastic policies. After the Second Crusade these orders began steadily to gain popularity and support. As they attracted men and wealth, and as the Crusading movement became part of the extended politics of Western Europe, the orders themselves became players in European politics. They established chapters throughout the West, both as recruiting bases and as a means to funnel money to the East; they built and fortified great castles; they sat on the councils of princes; and they too became rich and entrenched. In the years between the failure of the Second Crusade and 1170, when the Muslim prince Saladin came to power in Egypt, the Latin States were on the defensive but were able to maintain themselves. But in 1187 Saladin inflicted a major defeat on a combined army at Hattin and subsequently took Jerusalem. The situation had become dire. In response to the Church’s call for a new, major Crusade, three Western rulers undertook to lead their forces in person. These were Richard I, the Lion-Hearted of England, Philip II of France, and Frederick I, called Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor. Known as the Third Crusade, it has become perhaps the most famous of all Crusades other than the First Crusade, though its role in legend and literature greatly outweighs its success or value. The three rulers were rivals. Richard and Philip had long been in conflict over the English holdings in France. Though English kings had inherited great fiefs in France, their homage to the French king was a constant source of trouble. Frederick Barbarossa, old and famous, died in 1189 on the way to the Holy Land, and most of his armies returned to Germany following his death. Philip II had been spurred into taking up the Crusade by a need to match his rivals, and he returned home in 1191 with little concern for Eastern glories. But Richard, a great soldier, was very much in his element. He saw an opportunity to campaign in the field, to establish links with the local nobility, and to speak as the voice of the Crusader states. Though he gained much glory, the Crusaders were unable to recapture Jerusalem or much of the former territory of the Latin Kingdom. They did succeed, however, in wrestling from Saladin control of a chain of cities along the Mediterranean coast. By October 1192, when Richard finally left the Holy Land, the Latin Kingdom had been reconstituted. Smaller than the original kingdom and considerably weaker militarily and economically, the second kingdom lasted precariously for another century. CRUSADES OF THE 13TH CENTURY After the disappointments of the Third Crusade, Western forces would never again CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template threaten the real bases of Muslim power. From that point on, they were only able to gain access to Jerusalem through diplomacy, not arms. In 1199 Innocent III called for another Crusade to recapture Jerusalem. In preparation for this Crusade, the ruler of Venice agreed to transport French and Flemish Crusaders to the Holy Land. However, the Crusaders never fought the Muslims. Unable to pay the Venetians the amount agreed upon, they were forced to bargain with the Venetians. They agreed to take part in an attack on one of the Venetians’ rivals, Zara, a trading port on the Adriatic Sea, in the nearby Kingdom of Hungary. When Innocent III learned of the expedition, he excommunicated the participants, but the combined force captured Zara in 1202. The Venetians then persuaded the Crusaders to attack the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, which fell on April 13, 1204. For three days the Crusaders sacked the city. Subsequently the Venetians gained a monopoly on Byzantine trade. The Latin Empire of Constantinople was established, which lasted until the recapture of Constantinople by the Byzantine emperor in 1261. In addition, several new Crusader states sprang up in Greece and along the Black Sea. The Fourth Crusade did not even threaten the Muslim powers. Trade and commerce had triumphed, as Venice had hoped, but at the cost of irreparably widening the rift between the Eastern and Western churches. Crusades after the Fourth were not mass movements. They were military enterprises led by rulers moved by personal motives. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II vowed to lead a Crusade in 1215, but for domestic political reasons postponed his departure. Under pressure from Pope Gregory IX, Frederick and his army finally sailed from Italy in August 1227, but returned to port within a few days because Frederick had fallen ill. The pope, outraged at this further delay, promptly excommunicated the emperor. Undaunted, Frederick embarked for the Holy Land in June 1228. There he conducted his unconventional Crusade almost entirely by diplomatic negotiations with the Egyptian sultan. These negotiations produced a peace treaty by which the Egyptians restored Jerusalem to the Crusaders and guaranteed a ten-year respite from hostilities. However, Frederick was ridiculed in Europe for using diplomacy rather than the sword. In 1248 Louis IX, Saint Louis of France, decided that his obligations as a son of the Church outweighed those of his throne, and he left his kingdom for a six-year adventure. Since the base of Muslim power had shifted to Egypt, Louis did not even march on the Holy Land; any war against Islam now fit the definition of a Crusade. Louis and his followers landed in Egypt on June 5, 1249, and the following day captured Damietta. The next phase of their campaign, an attack on Cairo in the spring of 1250, proved to be a catastrophe. The Crusaders failed to guard their flanks, and as a result the Egyptians retained control over the water reservoirs along the Nile. By opening the sluice gates, they created floods that trapped the whole Crusading army, and Louis was forced to surrender in April 1250. After paying an enormous ransom and surrendering Damietta, Louis sailed to Palestine, where he spent four years building fortifications and strengthening the defenses of the Latin Kingdom. In the spring of 1254 he and his army returned to France. King Louis also organized the last major Crusade, in 1270. This time the response of the French nobility was unenthusiastic, and the expedition was directed against the city of Tunis rather than Egypt. It ended abruptly when Louis died in Tunisia during the summer of 1270. The tale of the Crusader states, after the mid-13th century, is a sad and short one. Though popes, some zealous princes—including Edward I of England—and various religious and political thinkers continued to call for a Crusade to unite the warring armies of Europe and to deliver a smashing blow to Islam, later efforts were too small and too sporadic to do more than buy time for the Crusader states. With the fall of ‘Akko (Acre) in 1291, the last stronghold on the mainland was lost, though the military religious orders kept garrisons on Cyprus and Rhodes for some centuries. However, the Crusading impulse was not dead. As late as 1396 a large expedition against the CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Ottoman Turks in the Balkans, summoned by Sigismund of Hungary, drew knights from all over the West. But a crushing defeat at Nicopolis (Nikopol) on the Danube River also showed that the appeal of these ventures far outstripped the political and military support needed for their success. OTHER CRUSADES The expeditions to Outremer are thought of as the Crusades. Military-Christian enterprises and expeditions elsewhere are easily branded as misdirected or perverted Crusades, but there is really no significant difference between them. Medieval Christendom perceived itself as having a right or duty to expand, to convert and dominate Muslims and pagans, and to bring dissident Christians back to the fold. When English forces helped take Lisbon from the Moors in 1147, they were carrying out what seemed the true purpose of a Crusade. This was also true for German soldiers under the banner of the Teutonic Knights when they imposed Christianity on the pagans of eastern Germany and the Baltic in the 12th and 13th centuries. Since the Crusades had become the militant arm of Christian society, it seemed only logical to launch the Albigensian Crusade (see Albigenses). This was a war fought by the French kings and their vassals against heretics in the south of France from around 1210 to 1229. This use of the Crusading banner seems a hypocritical smoke screen, as the French knights took the lands of their enemies, savaged by the people, and became the new feudal lords. But the distinction between what happened in France, in Jerusalem, or in Rîga in the Baltic was one of place and time, not of essence. As late as the 15th century, this extension of the Crusading ideal to areas outside the Holy Land was a powerful force when directed against a specific opponent. When national feeling and the adoption of religious ideas later associated with the Protestants made Bohemia a threat to European stability, at least in the eyes of the Holy Roman Empire and the pope, a Crusade was declared against Hussites, who were named for John Hus, their first leader. Some decried this as a false Crusade, saying that greed was being sanctified by ecclesiastical banners. But most of Europe endorsed the brutal warfare and the reimposition of Catholicism. This was, in their eyes, a Crusade for Christ’s church and people, as valid as any of the expeditions to the Holy Land. http://history-world.org/crusades.htm CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Packet for Students Activity Gregory VII: Call for a "Crusade", 1074 [Thatcher] Gregory VII barely missed the honor of having begun the crusading movement. His plan is clear from the following letter. The situation in 1095 was not materially different from that in 1074, and it is probable that Urban II, when he called for a crusade, had nothing more in mind than Gregory VII had when he wrote this letter. Gregory was unable to carry out his plans because he became involved in the struggle with Henry IV. Gregory, bishop, servant of the servants of God, to all who are willing to defend the Christian faith, greeting and apostolic benediction. We hereby inform you that the bearer of this letter, on his recent return from across the sea [from Palestine], came to Rome to visit us. He repeated what we had heard from many others, that a pagan race had overcome the Christians and with horrible cruelty had devastated everything almost to the walls of Constantinople, and were now governing the conquered lands with tyrannical violence, and that they had slain many thousands of Christians as if they were but sheep. If we love God and wish to be recognized as Christians, we should be filled with grief at the misfortune of this great empire [the Greek] and the murder of so many Christians. But simply to grieve is not our whole duty. The example of our Redeemer and the bond of fraternal love demand that we should lay down our lives to liberate them. "Because he has laid down his life for us: and we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren," [1 John 3:16]. Know, therefore, that we are trusting in the mercy of God and in the power of his might and that we are striving in all possible ways and making preparations to render aid to the Christian empire [the Greek] as quickly as possible. Therefore we beseech you by the faith in which you are united through Christ in the adoption of the sons of God, and by the authority of St. Peter, prince of apostles, we admonish you that you be moved to proper compassion by the wounds and blood of your brethren and the danger of the aforesaid empire and that, for the sake of Christ, you undertake the difficult task of bearing aid to your brethren [the Greeks]. Send messengers to us at once inform us of what God may inspire you to do in this matter. In Migne, Patrologia Latina, 148:329 trans. Oliver J. Thatcher, and Edgar Holmes McNeal, eds., A Source Book for Medieval History, (New York: Scribners, 1905), 512-13 http://www.fordham.edu/Halsall/source/g7-cde1078.asp CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Assessment Activity Create a timeline of the four crusades. List dates of each crusade and give a brief description of the events and causes. YEAR CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Homework Activity Read the attached source on the crusades and view the various recruitment posters. Make your own recruitment poster on the crusades. At the bottom of each poster include a brief description of what you are trying to say through your poster. At the beginning of the next class, you will put your poster up around the classroom and have the opportunity view others posters around the classroom. CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Recruitment Poster Examples CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template CSULB History Social Science Lesson Plan Template Bibliography Halsall Paul, 2011. “Gregory VII: Call for a Crusade, 1074.” Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University. 14 May 2013. <http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/einhard.asp#Generosity>. “The Crusades.” International World History Project. 14 May 2013. < http://historyworld.org/crusades.htm>.