* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

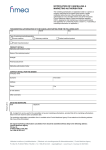

Download IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA GAUTENG DIVISION

Myron Ebell wikipedia , lookup

Global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

General circulation model wikipedia , lookup

Climatic Research Unit documents wikipedia , lookup

Climate change feedback wikipedia , lookup

Low-carbon economy wikipedia , lookup

Fred Singer wikipedia , lookup

ExxonMobil climate change controversy wikipedia , lookup

2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference wikipedia , lookup

Climate sensitivity wikipedia , lookup

Climate change denial wikipedia , lookup

Climate resilience wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on human health wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Attribution of recent climate change wikipedia , lookup

Economics of climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Politics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Tuvalu wikipedia , lookup

Climate change adaptation wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Australia wikipedia , lookup

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change wikipedia , lookup

Mitigation of global warming in Australia wikipedia , lookup

German Climate Action Plan 2050 wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Media coverage of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Economics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Canada wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on Australia wikipedia , lookup

Climate change, industry and society wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme wikipedia , lookup