* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Ch 10 – Climate Change

Climate change, industry and society wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate-friendly gardening wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Global warming wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Climate change feedback wikipedia , lookup

Emissions trading wikipedia , lookup

Economics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Kyoto Protocol wikipedia , lookup

Years of Living Dangerously wikipedia , lookup

German Climate Action Plan 2050 wikipedia , lookup

Kyoto Protocol and government action wikipedia , lookup

Climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in New Zealand wikipedia , lookup

2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference wikipedia , lookup

Low-carbon economy wikipedia , lookup

Carbon governance in England wikipedia , lookup

Economics of climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Politics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report wikipedia , lookup

Mitigation of global warming in Australia wikipedia , lookup

Carbon emission trading wikipedia , lookup

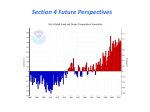

Chapter 10 Climate Change: Regulating Emissions This chapter covers climate change and its impact on the energy sector. It discusses (i) climate change and the energy sector; (ii) international climate control strategies; (iii) domestic climate change control strategies; and (iv) the cost and effectiveness of greenhouse gas controls. 10.1 causes/impacts of climate change, including GHG emissions from power plants 10.2 international politics behind climate control, including Kyoto Protocol and post-2012 negotiations 10.3 domestic climate change strategies at federal, state and regional levels, as well as judicial responses to those strategies 10.4 costs, benefits, and effectiveness of GHG controls. When reading this chapter, think about the greenhouse gas (GHG) effect on climate change. Compare the approach of the United States with the approach taken throughout Europe. Should the U.S. have adopted mandatory GHG emission standards when most European countries did? Next, consider the reasons why the United States is so reluctant to sign the Kyoto Protocol. Think about the actions individual states have taken to moderate GHG emissions, and the impact state regulations have on federal law. Finally, consider the cost of reducing GHG emissions. At what point will the U.S. decide that the benefits of reducing GHG emissions outweigh the costs? Some questions to consider when reading the chapter: 1. What is a “safe” amount of climate change, and what emission patterns over time are consistent with that level of “safe” change? 2. At what point should the United States take action to change our patterns of energy use? 3. What impact would a cap-and-trade emissions scheme have on reducing GHG emissions? 4. What are the problems of the EU-ETS? Should the U.S. adopt a similar model? 5. What are the significant flaws in the Kyoto Protocol, and can they be fixed? 6. What impact will the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) have on other states seeking to reduce GHG emissions? 7. Do you agree that the benefits of taking steps to solve global warming outweigh the costs of taking action? 10.1 Climate Change and the Energy Sector There is a consensus among most climate scientists that GHG emissions are transforming the Earth’s climate. No other environmental issue poses as great a difficulty to the energy sector as does GHG emissions. GHG emissions come from the combustion of fossil fuels that contain carbon (fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas). Those emissions have increased the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Scientists believe that if action is not taken to reduce these emissions, temperature levels will increase and cause drastic changes to the planet. Fortunately, it seems as though there is an international trend that advocates reducing those emissions. 10.1.1 GHG Emissions from Power Plants In 2006, the U.S. total for GHG emissions was 7,054 million metric tons carbon dioxide equivalent. The amount of GHG emissions a power plant emits depends on the type of fossil fuel burned. Coal-fired power plants emit the most emissions out of the fossil fuels. 10.1.2 What Causes Climate Change? The greenhouse effect is the process that occurs when GHG accumulate in the atmosphere and trap heat at the surface of the earth. This contributes to the increases in temperature levels. Though it is true that a certain level of GHG is needed to keep the earth at a habitable temperature, the increase in the levels of GHG means that more heat is trapped, and temperatures rise in correlation. There are three unchallenged facts about the greenhouse gas effect: (1) the atmospheric levels of GHG are increasing because of human activities; (2) the GHGs absorb and re-radiate in a way that heats the planet; and (3) these atmospheric changes are long-lasting, because the GHG stay in the atmosphere anywhere from decades to centuries. Most of the science related to global warming was developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (“IPCC”). The IPCC was established by the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorlogical Organization. Those organizations directed the IPCC to prepare a report every five years that indicates the consensus of scientists about the extent of climate change that was taking place, and what was causing the change. In November of 2007, the IPCC stated that the planet is warming, that human-generated emissions were the cause, and that reductions in GHG emissions needed to start immediately to mitigate the global climate. 10.1.3 Impacts of Climate Change One of the significant impacts of climate change is the direct effect on crop yields. Further, the range or number of pests that affect plants, or diseases that threaten animals and human health will also be impacted by the climate change. Water supplies throughout the world will be affected; episodes of drought and flooding will also impact the global community. Additionally, the effect on natural ecosystems (such as a rainforest) is also a cause for concern. In 2009, the EPA issued a summary saying that GHG emissions threaten public health and welfare. 10.2 International Politics of Climate Change [introduction] 10.2.1 Early Initiatives In 1992, the world’s industrial leaders and developing nations pledged to reduce GHG at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. However, implementation of the non-binding goal to reduce emissions proved ineffective. The developing nations, as well as the already developed nations, found it hard to coordinate positions. The convention failed to provide any targets or timetables; instead, it only relied on the goodwill of nations. 10.2.2 The Kyoto Protocol Then, in 1997, the Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) adopted the Kyoto Protocol. Under this protocol, the EU will be responsible for an 8% reduction in GHG emissions, but will have the authority to assign different targets to different countries. Although most nations involved signed and ratified the protocol, the United States did not. In 2001, President Bush rejected the Kyoto Protocol, saying it was too costly and unfairly excluded developing nations such as India, China and Brazil. President Bush argued that the protocol would place an unfair burden on developed countries, particularly the United States. The Kyoto Protocol established three “flexibility mechanisms” to help Annex B nations lower the costs of achieving admissions targets. First, it established Joint Implementation. This allows Annex B nations to undertake emission reduction projects in other Annex B nations, and then receive a share of the emissions reduction. Secondly, it created a Clean Development Mechanism (“CDM”). This allowed Annex B nations to undertake projects to reduce emissions in developing nations without targets (called nonAnnex B), and then claim credit for the emission reduction the projects achieve. Finally, the Kyoto Protocol established Emissions Trading. Emissions trading allows nations which have excess emissions reduction units to sell them to countries that are over their emissions targets. Emissions trading gained popular support with the European Union. After the Kyoto Protocol was founded, the then existing 15 nations of the EU agreed to an 8% reduction in GHG. In an effort to incorporate more countries into the emission reduction program, the E.U. emissions trading system (“EU-ETS”) was officially founded in 2005, and included 25 countries. The trial period of the program went from 2005-2007, and although there were flaws in the system, the trial period succeeded in creating mechanisms for effecting greater GHG emission reduction in the future. 10.2.3 From Bali to Copenhagen: Negotiating a Post–2012 Agreement The Kyoto Protocol garnered a great deal of criticism for not including enough countries, including the United States-one of the greatest producers of GHG emissions. In fact, because the agreement didn’t incorporate some of the largest producers of GHG, less than one-third of total global emissions were covered. Proponents of the Kyoto Protocol claim that it was a great step in the right direction and offer examples of other diplomatic successes like the WTO or the European Union, which took time to form and adapt. Soon after ratification of the Kyoto Protocol, further meetings took place in Bali and Copenhagen to make changes that would help lower GHG emissions further. The achievements in Bali were focused on getting a greater number of countries to address global warming. In Bali, the parties wanted to make sure that GHG output peaks in the next 10 to 15 years and will then decline dramatically afterwards to about half as much by the middle of the twenty-first century. In order to obtain that goal, the parties recognized that industrialized and developing countries would have to make substantial cuts. Further, the United States, India, and China would have to greatly lower their emissions. The terms put specific cuts on countries, but the United States was unwilling to accept those terms. In addition, the Bali meetings addressed issue revolving around technology. The developing countries wanted already developed nations to be accountable for actions to better technology for clean energy. This would be accomplished by requiring the developed nations’ actions to be immeasurable, reportable and verifiable. Although the United States did not agree with the language used, it went along with the proposal because most other countries believed it was a good idea. Developed nations also wanted language incorporated that provided steps for developing countries to take to mitigate emissions. Financing was another major issue in Bali. In order to bring emission levels down only to the levels in 2007, the convention would need to raise $200–210 billion by 2030. The Bali Action Plan provides action to encourage investment for better technology and to help developing countries carry out mitigation plans. During the Copenhagen convention, world leaders wanted to reach an agreement that would address five main components: 1. Enhanced action to assist the most vulnerable and the poorest in adapting to the impact of climate change; 2. Ambitious emission reduction targets for all industrialized countries on an individual basis; 3. Nationally appropriate mitigation actions by developing countries to limit the growth of their emissions, while safeguarding economic growth and sustainable development, with the necessary support; 4. Significantly scaled-up financial and technological resources; and 5. An equitable governance structure to guide financial resources. In the end, participating nations adopted the Copenhagen Accord, even though it fell short of putting a cap on GHG emissions. The Copenhagen Accord provided that nations must take action to keep the Earth’s temperature from increasing more than 2* degrees Celsius, on average. As we move forward in climate change negotiations, the United States and China will play a crucial role in accomplishing tactics to curb climate change. Together, these two countries account for over 40% of the world’s GHG emissions. Although nonclimate related issues between the U.S. and China often puts them at odds, any kind of resolution going forward must incorporate them both. Each country stands to share in long terms gains from climate-related policy changes. 10.3 Domestic Climate Change Control Policies While Europe was busy creating mandatory schemes to reduce GHG emissions, the United States only promoted voluntary GHG emission reduction. President Obama’s election changed the way other nations viewed the United States’ stance on GHG emission reduction. Although some organizations (i.e., the Chamber of Commerce and the American Petroleum Institute) continue to resist efforts to reduce GHG emissions, a large number of companies are acknowledging the threat of climate change and are vowing to take action. Some companies and organizations began to work with environmental groups to found the U.S. Climate Action Partnership. While federal law concerning emissions reductions is slow to occur, many states and regions of states are working together to reduce their emissions. 10.3.1 Federal Government Strategies Prelude to Clean Air Act Regulation. The EPA did not regulate carbon dioxide emissions under the Clean Air Act during the Bush Administration, which stressed voluntary action rather than mandatory federal laws. In 2007, the Supreme Court issued the opinion for Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497 (2007), which led to a change in the law and outlook for mandatory constraints on carbon dioxide. The Massachusetts v. EPA case arose when rulemaking petitions were filed by private organizations seeking to have a rule made to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from new automobiles under the Clean Air Act. The EPA decided that carbon dioxide did not fall under the scope of the Clean Air Act because it was not an “air pollutant” as defined in the Clean Air Act. When the case reached the Supreme Court, there were two primary issues: (1) did Massachusetts have standing, and (2) did the EPA have authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon dioxide emissions. Ultimately, the Supreme Court disagreed with the EPA and held that carbon dioxide did fall under the definition of “air pollutant.” To bring suit, the state of Massachusetts had to show standing. Part of showing standing is having an injury in fact. The Court found that Massachusetts had shown the sea level had risen as a result of global warming. Because Massachusetts owns coastal land, that was enough to show an injury in fact. The Court also found causation since the EPA did not dispute the relation between GHG and global warming and, despite this relationship, the EPA refused to regulate GHGs (here, carbon dioxide). Last, the Court found redressability since reducing emissions would slow the rate of change of global emissions. Having found that the EPA had the statutory authority to regulate GHG, the Court needed to decide whether the EPA’s reasoning in not regulating carbon dioxide emissions were consistent with the Clean Air Act. The EPA stated that even if it had the authority to regulate GHG emissions, the agency would not do so because global warming was an international problem making regulation a piecemeal approach to the problem at odds with the President’s comprehensive approach. The EPA also claimed that they would have to tighten mileage standards, which would make them regulate something intended for the Department of Transportation. The Court rejected both of these claims, finding that their reasoning was not in line with the statutory text. Ultimately, the Court found that the EPA’s decision was arbitrary and capricious. Agency regulation of CO2 emissions. Shortly after the Court decided Massachusetts v. EPA, the EPA Environmental Appeals Board dealt with In re Deseret Power Electric Cooperative. While the former had dealt with mobile sources of GHG emissions, Deseret dealt with stationary sources. In this case, Deseret Power proposed a major modification to an existing stationary generating unit (a coal-powered facility). In order to add the modification, Deseret Power required a prevention of significant deterioration (PSD) permit. The permit was initially granted, and the Sierra Club sought review by the Environmental Appeals Board. The question was whether the permit must contain a “best available control technology” (BACT) emissions limit for carbons - each side debated whether carbon was a pollutant subject to regulation under the CAA. The Board determined that the EPA erred by not appropriately considering carbon dioxide in issuing an air permit. The Board remanded the permit and asked for the permitting body to reconsider the permit upon further consideration of carbon dioxide, and, subsequently, upon consideration of whether carbon dioxide emissions by stationary sources are subject to regulation under the CAA. While the case did not provide a definitive answer on the issue, it signaled for the incoming Obama administration that uncertainty relating to the handling of carbon dioxide in permitting decisions remains an issue of national scope that required attention. EPA rulemaking on CO2 emissions. Following Massachusetts v. EPA (which dealt with GHG emissions from mobile sources) and In re Deseret (which dealt with GHG emissions from stationary sources), the EPA issued three proposed rules to regulate CO2 emissions directly under the Clean Air Act. The three rules included (1) regulation on emissions from mobile sources, (2) regulation on emissions from stationary sources that emit more than specified amounts of GHGs, and (3) regulation on the actual reporting of GHG emissions. Along with these three rules, the EPA also allowed California’s waiver so that it could implement its own auto GHG emissions standards. Vehicle Emissions Standards (CAA §202(a) and California Waiver (CAA §209)). California was the first state to set its own vehicle pollution standards. California has asked, and ultimately been granted, a waiver from the EPA to set its own vehicle emission standards since 1975. California renewed its request in 2005 and, after much deliberation, was again conditionally granted the waiver on June 30, 2009. California’s waiver was conditioned on, first, the understanding that the state’s standards would be no less strict than federal standards. Second, California agreed to conform its own standards to the federal standards between 2012 and 2016, with the flexibility to make standards more stringent before and after this period. This conditional agreement was centered, in large part, upon giving the auto industry uniform, rather than individualized, piecemeal standards. The standards - which require emissions reductions for new passenger cars, SUVs, and pickup trucks sold in California - may be adopted by other states under section 177 of the CAA (so long as the standards are identical to California’s). Shortly after California’s waiver was granted, and other states adopted the same standards, auto dealers and automakers across the nation challenged the standard. Auto industry plaintiffs argued that GHG standards were related to fuel economy standards, which are expressly preempted by the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA). Ultimately, these challenges failed. The winning argument was that automakers had a number of means at their disposal to reduce GHG emissions, only one of which was to increase fuel economy. In 2009, the EPA set federal standards for GHG emissions in vehicles. In response to Massachusetts, the EPA cited two findings as prerequisites to its authority to regulate GHG emissions from vehicles under the CAA: (1) GHGs in the atmosphere endanger the public health and welfare, and (2) emissions from vehicles (and their engines) contribute to the atmospheric concentration of these GHGs. While the federal standards are less rigid than those in China and Europe, they are certainly a step in the right direction. Major Stationary Sources (CAA Title I). In September 2009, the EPA announced a proposed rule that would apply to major stationary sources emitting over 25,000 tons per year (“tpy”) of GHGs. The rule would be applied in determining which emitters would require certain permits. This threshold was set so that minor emitters (i.e., small retailers, farms, restaurants, churches, etc.) would not face government regulation, and because it would cover nearly 70 percent of the national GHG emissions from stationary sources, including those from the largest emitters (i.e., power plants, refineries, and cement production facilities). GHG Reporting Requirement. Also in September 2009, the EPA announced its rule on mandatory reporting requirements. The Reporting Rule requires certain direct GHG emitters, fossil fuel and industrial gas suppliers, and manufacturers of vehicles and engines to collect and report information about GHG emissions of their operations and/or products. An estimated 10,000 facilities are required to report under this rule, who collectively account for about 85% of the nation’s GHG emissions. There are significant fines levied against those required to report for each day that they violate the rule. There are pros and cons to addressing the issue of climate change via both legislation and regulation. Many, including President Obama, have expressed a preference for the former: legislation is more expansive (regulation often requires separate rule-making determinations for separate industries), it is more efficient (individual rulemaking proceedings for specific industries that would be time consuming and contentious), and legislation allows for creative supplements (i.e., market-based mechanisms such as cap-and-trade schemes), unlike the typical permit-based regulatory schemes. However, legislation may also have its downsides. The proposed emissions trading plan proposed under the American Clean Energy and Security Act (ACES), which ultimately failed, would have required a complex network of new government entities and regulations, and a complex market for trading pollution permits. Many, therefore, have advocated the use of a simple carbon tax. Supporters say that a carbon tax would be a less bureaucratic and more effective means of reducing GHG emissions than a cap-and-trade scheme. However, others argue that a carbon tax wouldn’t be so simple or worthwhile. No tax is “simple,” and every tax contains loopholes and opportunities for firms and individuals to take advantage of them. Furthermore, a carbon tax would require frequent readjustment by the government in order to continually reduce emissions because, unlike a cap-and-trade system, there would not be a market-regulating incentive/pressure to continually reduce emissions. Some believe that a cap-and trade system works effectively like a carbon tax. Ultimately, it will be interesting to see whether regulation or legislation will predominantly control our country’s emissions; if it is the latter, it will also be interesting to see which system (capand-trade or carbon tax) will prevail. The debate is ongoing. For a quick explanation on cap-and-trade schemes, see the following video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zfglMLcjRrM There are some cap-and-trade systems, both domestic and abroad, already in place. For example, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in the northeastern United States and the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme. Both may serve as a model for an eventual, federally-implemented system here in the U.S. 10.3.2 State and Regional Strategies According to the Congressional Research Service, if American states were viewed as individual nations, 21 of them would rank in the top 60 countries for producing GHG emissions. Both state and local governments have created a wide variety of laws and policies to help combat GHG emissions. Thirty states now have state action plans that examine the sources of GHG emissions, and then form a task force to work with those sources to reduce emissions. Additionally, these task forces look at available policy options and GHG-reduction measures to determine which is most appropriate for the specific state. State action plans vary greatly between states, but generally do nothing more than recommend legislative action to state officials. For instance, many plans set statewide GHG emissions targets, break total emissions down by industry/geographic area, urge industry to record emissions, report emissions to the climate change task force, and in some states, establish emissions reduction guidelines. Case Study: California Global Warming Solutions Act. California is one of the largest emitter of GHGs in the world. In 2006, it established a landmark law to reduce GHG emissions. The Global Warming Solutions Act required the California Air Resources Board to develop regulations and implement a state-wide program to reduce the state’s GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. Additionally, California reviewed emissions-trading schemes and proposed a cap-and-trade scheme to begin in 2012. Although there is much debate over carbon off-set programs such as cap-and-trade schemes, there is no denying the popularity of those programs. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). CCS refers to the technologies used to stop GHG emissions from getting into the atmosphere. These technologies trap carbon dioxide and store it underground. Over fourteen states have recently enacted laws that encourage CCS by state-regulated utilities. The EPA has proposed to regulate CCS under the Safe Drinking Water Act. As of now, there are three main types of CCS technology: (1) precombustion; (2) post-combustion; (3) oxyfuel technology. Pre-combustion removes carbon from fossil fuels before combustion. This technology is frequently used with coal gasification. Post-combustion removes carbon dioxide from power plants before it has a chance to enter the atmosphere. Finally, oxyfuel technology burns fuels in a pure oxygen atmosphere. This turns emission from smokestacks into just water vapor and carbon dioxide. When burned in this manner, carbon dioxide is easily separated from the water vapor. Once the carbon dioxide is trapped, it is moved to a dump location and is stored at least 800 meters underground. While this seems effective way to store carbon dioxide, the United States has designated very few dump-sites. Further, the cost and time involved in the process is significant (so much so that there are no commercial carbon dioxide storage facilities in the U.S.). Besides cost, liability and property rights plague the use of CCS technology. The potential damage resulting from a carbon dioxide leak is significant, and tort liability may limit the number of companies willing to run storage sites. Determining who owns the earth 800 meters below storage facility also presents numerous issues. The House created the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (“ACES”) to help promote CCS technology. ACES would give the EPA regulatory authority over CCS sites, and would provide liability limits for site owners. ACES also aimed to establish the Carbon Storage Research Corporation, which would charge a power-use fee meant to fund CCS projects. Finally, ACES would require all electric generating units permitted after 2015 to meet a New Source Performance Standard. 10.3.3 Judicial Responses As global warming awareness increases, so do GHG and climate change-related lawsuits. These cases are difficult to prove given the wide array of scientific data on global warming and climate change. Plaintiffs typically rely on tort and property law principles when filing claims. Defendants use a wide range of defenses in climate related claims; the defenses range from claims of inconclusive evidence to the political question doctrine. The sample cases in the text, along with the Supreme Court’s decision in Connecticut v. American Electric Power Co., demonstrate the broad array of issues in GHG and climate change-related cases. 10.3.4 Voluntary Reduction Strategies Many companies utilize voluntary reduction strategies such as offsets and emissions control technology, but environmentalists argue that these efforts are fruitless and only delay a mandatory regulation program. Some cynics argue that “offsets” do not truly offset environmental damage. As some of these cynics say, “You can ‘offset’ the emissions you generate on a cross-country airplane trip, but you are still taking the trip.” Industry-set emissions “baselines” are an example of how voluntary reduction strategies are unreliable. Some companies will compare their emissions to a “baseline” that factors in alternate – and dirtier – business methods. For instance, a company can increase emissions by building a gas-burning plant and claim “emissions reductions” based on the fact that, had they built a coal-burning plant instead, GHG emissions would have been higher. 10.4 Toward a Low-Carbon Future: The Cost and Effectiveness of GHG Controls The International Energy Agency (“IEA”) recently released the World Energy Outlook. This report looked at the global impact of the recent financial crisis, and how that crisis affected the energy sector. One of the more notable findings was that the benefits of taking serious steps to combat global warming far outweigh the costs of doing so. Even with a limited list of benefits, the global community is much better off taking action against global warming. Overall, taking action against global warming is in the world’s best interest.