* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 1 Removing the Constraints on Our Choices: A Psychobiological

Metastability in the brain wikipedia , lookup

Psychophysics wikipedia , lookup

Neuroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

Neuroethology wikipedia , lookup

Neuroscience in space wikipedia , lookup

Neuroplasticity wikipedia , lookup

Brain Rules wikipedia , lookup

Holonomic brain theory wikipedia , lookup

Central pattern generator wikipedia , lookup

Evoked potential wikipedia , lookup

Binding problem wikipedia , lookup

Feature detection (nervous system) wikipedia , lookup

Stimulus (physiology) wikipedia , lookup

Time perception wikipedia , lookup

Biology and consumer behaviour wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and psychology wikipedia , lookup

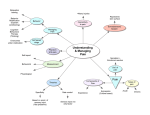

Removing the Constraints on Our Choices: A Psychobiological Approach to the Effects of Mindfulness-Based Techniques Nava Levit Binnun Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya Rachel Kaplan Milgram Yaakov Raz Tel Aviv University Mindfulness practice, developed more than 2500 years ago as one of several Buddhist paths for liberation from suffering, is an enquiry into human existence that has much in common with existential themes. Jon Kabat-Zinn, a contemporary expert on mindfulness, has defined mindfulness practice as “the paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally” (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Nyanaponika Thera (1972), a Buddhist monk and scholar, called mindfulness “the clear and single-minded awareness of what actually happens to us and in us at the successive moments of perception” (p. 5). According to contemporary Buddhist scholars, mindfulness practice can move an individual toward freedom by guiding him or her to let go of notions of permanent structures of self and reality (Rahula, 1959; Joko Beck, 2000; Kornfield, 2008). Mindfulness is part of many Buddhist practices. Currently, there are a variety of Western mindfulness-based interventions, ranging from stand-alone programs such as the eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program (MBSR) to others that combine mindfulness with 1 existing psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (for a review, see Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009). For the purposes of this chapter, we will use the term “mindfulness” broadly, not in relation to a specific program but in reference to the “construct, mode of awareness, meditation practice, or psychological practice” (Chambers, Gullone & Allen, 2009). Recently, psychologists and neuroscientists have taken an interest in mindfulness, and the number of published mindfulness studies has grown exponentially over the last decade. Following mindfulness skill development, people report an increase in well-being and a reduction in stress, anxiety, and depression. In addition, accumulating empirical evidence suggests that people who possess higher natural levels of mindfulness—even without formal meditation practices—report feeling more joyful, inspired, grateful, hopeful, content, vital, and satisfied with life (for a review, see Greeson, 2009). According to first-person reports, the phenomenological experience of mindfulness is that of an increased sense of freedom and meaning (Peled, 2007). Although knowledge regarding the psychological and physiological effects of mindfulness practices is rapidly increasing, it is still not clear how these empirical findings translate to the first-person experience of an increased sense of freedom. In this chapter, we integrate wisdom from two fields that are not often reviewed together—occupational therapy and Buddhism—to explore how mindfulness may remove the constraints on basic biological systems, such as the sensory system, which in turn can lead to a greater phenomenological sense of freedom. We begin with a review of research in the field of occupational therapy, which demonstrates how differences in the "tuning" patterns of sensory systems and the ways in which 2 they are “coupled” with other systems affect people’s choices, decisions, and values. We then examine the Buddhist view that senses may be experienced as restrictive limits through which the world is filtered and formulated into particular mental constructions that guide choices. Finally, we show how these ideas are grounded in neuroscience findings, and how bridging the gap between biological and phenomenological findings regarding mindfulness practice can lead to greater insight. Insights from Occupational Therapy People Differ in Their Sensory Processing Patterns Disciplines such as occupational therapy are providing a wealth of information about how individuals differ in the way they process sensory information and how these processing methods guide their choices and behavior (Dunn, 2001; Engel-Yeger, 2008). At a very basic level, humans are biological machines that create models of reality via input/output systems. Input from the world around us and from our bodies enters the brain through our exteroceptive sensory systems (visual, auditory, somatosensory, olfactory, and gustatory) and interoceptive systems (vestibular, proprioceptive, kinesthetic, and nociceptive). In certain conditions such as autism, schizophrenia, ADHD, and even normal fatigue, individuals often exhibit extreme patterns of sensory processing, such as being over-reactive or under-reactive to incoming stimuli (for review, see Dunn, 2001). Recently, these extreme patterns of sensory processing have regained scientists' attention, because they may provide insight into these abnormal conditions. For instance, the rigid and inflexible behavior often observed in autism can be explained by oversensitivity to stimuli and the consequent overwhelming of sensory systems (Baranek 1997; Markram et al., 2007). 3 A smaller but intriguing body of research focuses on the differences in sensory patterns in healthy people without disabilities. Distinct patterns of noticing and habituating to sensory information have been found in healthy preschoolers, for example (McIntosh et al., 1999; EngelYeger, 2008), and in healthy adults (Brown et al., 2001, Aron & Aron, 1997). These differences have been found using both self-report and physiological measures of autonomic (McIntosh et al., 1999; Brown et al., 2001) and central nervous system activity (Jagiellowicz et al., 2010). Recently, Dunn and colleagues found that people without disabilities can be situated on a continuum of neurological reactivity. People with low neurological thresholds notice sensory stimuli quite readily and experience more sensory events in daily life than others, whereas people with high neurological thresholds require more sensory input to generate reactions and responses (Dunn, 2001). Individual Differences in Sensory Processing Affect Variables Such as Choices, Temperament, and Values Dunn and colleagues have suggested that one’s threshold for incoming sensory stimuli can influence one’s choices and, consequently, one’s ability to live a satisfying life. They demonstrated that a relationship can be found between people’s neurological thresholds and their behavior, temperament, and personality. For instance, people with a high neurological threshold (i.e., those who experience only salient sensory stimuli) are often “sensation seekers” who enjoy sensory experiences and find ways to enhance and extend sensory experiences in daily life (Dunn, 2001). Examples include wearing perfume, smelling flowers, feeling vibrations in stereo speakers, seeking crowded events, and pursuing active and often extreme physical activities (Brown et al., 2001; Dunn 2001). Sensation seeking has been found to relate to dimensions of temperament such as openness, agreeableness, and extraversion (Engel-Yeger, Stern-Ellran, & 4 Levit-Binnun, 2011). Sensation seekers score relatively high on Sensory Profile Questionnaire items such as: “I enjoy being close to people who wear perfume or cologne” and “I like to wear colorful clothing” (Brown et al., 2001). People with low neurological thresholds are sensation avoiders. They stay away from distracting settings and often leave a room if others are moving, talking, or bumping into them. They create rituals for daily routines, which may be an attempt to generate familiar and predictable sensory patterns for themselves. When these rituals are interrupted, such people become unhappy (Brown et al., 2001; Dunn, 2001). Not surprisingly, they people are likely to score relatively high on negative affect and and the temperament trait neuroticism (Engel-Yeger et al., 2011). These individuals identify closely with such items on the Sensory Profile Questionnaire as “I choose to shop in smaller stores because I’m overwhelmed in large stores” and “I avoid standing in lines or standing close to other people because I don’t like to get too close to others” (Brown et al., 2001). Interestingly, these sensory patterns have been found to correlate not only with temperament but also with personal values (Sverdlik & Levit-Binnun, 2011) and attachment styles (Engel-Yeger et al., 2011). For example, sensation seeking correlates negatively with favoring conformity and tradition, and with avoidant attachment styles. Introducing the Concept of “Tuning” The human sensory systems are sensitive to a wide range of environmental signals. For example, the human ear is capable of detecting and discerning anything from a quiet murmur to the sounds of the loudest heavy metal rock concert. However, the fact that the sensory systems have such a wide detection range does not necessarily imply that people are all “tuned” similarly to the world. The information detected by the sensory receptors is modulated almost immediately 5 by subcortical areas in charge of arousal and vigilance, by top-down processes, and by processes in charge of habituation (a decreased response to familiar stimuli) and sensitization (an increased response to stimuli of importance to the organism). These processes, based on an individual’s genetic endowment and past experience, result in different neurological thresholds for incoming information—or, in our terminology, different “tuning patterns” of the sensory systems. Thus, although the biological systems responsible for sensation may have theoretically similar ranges of operation in most people, there are important individual differences in the tuning of these systems. Individuals Differ Not Only in How Their Sensory Systems are Tuned, But Also in How Their Sensory Systems Are “Coupled” to Other Systems At first glance, sensation avoiders and seekers seem to be opposite sensory types, representing two extremes on a continuum. However, another glance reveals that they actually share something in common: In both sensory types there seems to be an active regulating process in charge of balancing the amount of incoming sensory stimuli. For example, sensation seekers will be attracted to crowded places while sensation avoiders will be repelled by them. Although the behavioral outcome is very different, in both cases a regulatory attempt is taking place leading to an increase in sensations for the sensation seekers and a decrease in sensations for the sensation avoiders. Interestingly, Dunn et al. found that this regulatory process can itself represented on a continuum. That is, whereas individuals with high neurological thresholds and active regulatory processes would be termed sensation seekers, individuals with the same high neurological thresholds but with passive regulation may live their lives with many sensory events going unnoticed. Because they receive less sensory stimulation, they may not notice changes in the environment, such as when people enter the room, or changes related to their own bodies, 6 such as when they have food or dirt on their face. These individuals identify with items on the Sensory Profile Questionnaire such as “I don’t notice when people enter the room” (Brown et al., 2001). On the other hand, people with low neurological thresholds who are passive with respect to sensory regulation may have trouble limiting the amount of incoming stimulation. These people are easily distracted by movements, sounds, or smells. They notice food textures, temperatures, and spices more rapidly than others and they often let things happen without moving away from them. These individuals will often score high on Sensory Profile Questionnaire items such as: “I startle easily to unexpected or loud noises (e.g., vacuum cleaner, dog barking, telephone ring)” (Brown et al., 2001). The two axes that Dunn and colleagues have discussed – sensory reactivity (neurological threshold) and sensory regulation strategy (balancing the amount of incoming information) – suggest that people differ not only in their “tuning” patterns (high or low neurological threshold) but also in the way their sensory systems are “coupled” to other basic systems such as those in charge of regulating vigilance and alertness, and those in charge of emotional valence and action systems. Here we use the term coupling to refer to the fact that activity in one system will increase the probability of activity in another system. The more strongly the two systems are coupled, the greater the causal connection between them. The fact that people can have similar neurological thresholds but different regulation strategies suggests that people also differ in the coupling between systems and that coupling strength can constrain subsequent behavior and choices. Although the two axes described above do not entirely capture an individual’s sensory complexity—people have multiple sensory channels, each of which may have a different 7 neurological threshold—the four simplistic tuning patterns we have described show how particular sensory “tuning” and “coupling” patterns can influence choices and behavior. Insights from Buddhism In Buddhism, Individual Sensory Processing Is Central to Perception of the World and Constrains Actions and Choices Just as the view from occupational therapy emphasizes the role of individual sensory experiences in constraining behavior, so too does Buddhism place central importance on the role of sensation and perception in shaping human actions, choices, and understanding of the world. Buddhist texts organize human experience around the concept of suffering and propose that at the very basis of our existence there is unease, restlessness, and sometimes even physical and mental suffering. Buddhism attempts to explain the origins of this restlessness or unease and claims that at the root of suffering lie ignorance, clinging, and aversion. We suffer because we are unable to see that what we experience as a permanent structure of self and reality is actually an everchanging subjective construct. Furthermore, we cling to the desire that our experiences will play out according to our expectations, and when they don’t, we feel distressed and unhappy. This ignorance, according to the Buddhist texts, begins with a basic unawareness of how our perception is constrained by our genetic makeup, past experience, and needs. In turn, our perceptions themselves constrain our feelings and motivations, which in turn constrain our actions. Thus the Buddhist view, through a different framework and with slightly different definitions, emphasizes the strong link between sensory perception and behavior. Examining canonical Buddhist texts, which are based on the phenomenological experiences following 8 meditative self-inquiry, can therefore shed light on the fine details of subjective sensory processing and how they relate to well-being. Buddhism Emphasizes the Working of the Sensory Systems In the paticca-samuppada1, a canonical Buddhist text that presents a model of the causes of suffering (Figure 1), half of these causes concern the ways in which people sense and perceive reality. The other half of the causes in the model concern the ways in which we react to the world and create our self-identity and conception of reality. Importantly, the paticcasamuppada represents all these causes in the form of a circular chain, with each link (each cause) being conditioned by the preceding link as well as actively conditioning the following link. As described in the paticca-samuppada, the sensory process can be broken down into several interrelated stages. We fail to see how the combination of our experiences and needs govern us (link 1: “lack of self awareness”), and how this in turn influences the way our patterns and internal representations of the world are imprinted on us (link 2: “internal representation, patterns”). These representations influence how we are able to discriminate and discern external and internal stimuli (link 3: “discriminative consciousness”). These discrimination abilities constrain the way we organize both our experiences and our perceptions of the world by naming, labeling, and creating forms (link 4: “forms and names”). With our minds already disposed to discern, shape, and label certain kinds of objects, our senses become attuned to detect the sensory data associated with such objects, and overlook others (link 5: “attunement of senses”). These stages form filters that condition our contact with reality (link 6: “contact”). As they occur, incoming sensory experiences are immediately tinted in shades of “pleasant,” “unpleasant,” or “natural” (link 7: “sensations”). 9 Thus, our past experience will dispose us to a different level of active sensing—such as listening, seeing, smelling—as we experience different situations. For example, when observing an object such as a leaf, an artist may notice its various shades, a botanist may be attuned to its shape, and a gardener may notice that it needs watering. Thus, “an object of perception is designed by pre-knowledge, information, predispositions, needs and fears from the external object, which is allegedly the objective source [of] our sensations [of] it” (Aran, 1993). Notably, the main first half of the model provides a detailed description of filters and constrictions on the sensory processes that constrain our perception of reality. According to the model, these sensory processes directly condition our motives, feelings, clinging tendencies, actions, and development of self-concept, all of which are represented in the second half of the model (Figure 1). Since the model is circular, these motives, feelings, clinging, actions, etc., condition future sensory processes. The model therefore illustrates how human beings are trapped in a cycle that limits perceptions, actions, and choices. 10 Buddhism does not merely outline constraints; it also identifies exit points, or paths to liberation Importantly, each of the links in the model can serve as a means to break free from the endless cycle. The paticca-samuppada contains not only the Buddha’s teachings about the origins of suffering and conflict, but also a practical guide to the various exit points to liberation. It suggests that we have a choice of either being locked in to the same physical-mental patterns and constructions, or of unlocking these constraints. Thus, by becoming aware of the factors that condition or constrain our reality, we can break free of them. While the “letting go” of craving and clinging (central links in the second half of the model) is a Buddhist idea that is familiar to Westerners (Mikulas, 2007; Peled, 2007), the letting go of the constraints on our perceptions and senses (the first half of the model) is a less-familiar notion. According to the Buddhist view, just as letting go of craving and clinging can lead to 11 freedom, so too can awareness of the workings of the senses. Becoming aware of the working of our senses can increase our freedom in several ways. First, attending to sensory experiences, without projecting onto them past experiences or restricting them with labels, fears, and plans, expands them and enables new possibilities that have not been noticed before. Second, awareness of mental constrictions can loosen their restrictive power and enable us to “let go” of them, providing us with the possibility of choosing when they are indeed needed as restraints and when they are constraining and limiting us. Third, we can achieve a sense of freedom by cultivating the ability to hold an a similar, unbiased attitude toward what is pleasant and what is unpleasant. This skill, called “equanimity” in Buddhism, enables one to be less manipulated and controlled by likes and dislikes concerning a certain sensory experience and be able to choose more clearly the best actions and solutions. Mindfully “Retuning” the Senses: Another Path to Liberation How can we overcome ignorance of the links described in the Paticca Samuppada and see these invisible patterns, constructions, and automatic actions that rule us? Buddhism suggests mindfulness practice as a form of mental training that can lead to an awakening from ignorance and lack of awareness. In the Sati-patthana sutta2, which contains one of the earliest instructions for mindfulness practice, the Buddha teaches his disciples about “mindfulness" and its uses: How, monks, does a monk live contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the six internal and the six3 external sense-bases? The Buddha proceeds to teach the monks how to cultivate mindful awareness, how to gain insight into the workings of the visual system, and how to notice the “fetters,” which are the constraints and bonds on our sensory experience. Herein, monks, a monk knows the eye and visual forms [and the fetter that arises dependent on both (the eye and forms)]; he knows how the arising of the non-arisen fetter comes to be; he 12 knows how the abandoning of the arisen fetter comes to be; and he knows how the non-arising in the future of the abandoned fetter comes to be. The Buddha goes on to emphasize the importance of awareness to all of the senses, not just the visual sense. He knows the ear and sounds... the nose and smells... the tongue and flavors... the body and tactual objects..., and the fetter that arises dependent on both; he knows how the arising of the non-arisen fetter comes to be; he knows how the abandoning of the arisen fetter comes to be; and he knows how the non-arising in the future of the abandoned fetter comes to be. Thus, according to this text, mindfulness practice facilitates the development of a skill by which one can become aware of fetters (or mental constrictions, described in the Paticca Samuppada model) and let them go when they arise. Most contemporary mindfulness practices also emphasize awareness of moment-to-moment sensory experiences. Mindful awareness of a sensory experience without labeling it (e.g., “itch,” “knee pain”) can develop not only sensitivity to the subtle details of our experiences, but also an ability to stay with these experiences, suspend an immediate response, and create a space wherein a novel viewpoint and behavior may arise. Mindfulness practice can therefore have a profound effect on the filters and constrictions that cause our perception to be subjective and limited. By broadening our range of sensitivity, we are in essence “retuning” our senses. Thus, the Buddhist concept of mindfulness, like occupational therapy in the previous section, strongly relates sensory experiences to choices, actions, and therefore freedom. Discussion Both Occupational Therapy and Buddhism Suggest That the Way We Are “Tuned” to the World Can Greatly Influence Our Behavior and Decisions 13 We have shown how two distinct fields of wisdom, the occupational therapy and Buddhism, have realized, each in its own context and tradition of inquiry, how much the working of our senses can influence our behavior and constrain our range of choices. Choices have been defined by Schwartz, in a previous chapter in this volume, as “what enables each person to pursue precisely those objects and activities that best satisfy his or her own preferences within the limits of his or her resources.” The empirical and phenomenological evidence provided by Buddhism and occupational therapy demonstrate that the way we are “tuned”" to the world can greatly limit our preferences and resources. In this sense the term “tuning” is advantageous in that it can translate across fields of wisdom. Its wide accessibility is due to the fact that both Buddhism and occupational therapy acknowledge and emphasize that at a very basic level individuals differ in their fundamental patterns of sensory processing. The Buddhist view goes a step further in offering a detailed description of the subtle stages of sensory processing that can constrain our perception of reality and subsequently our actions and behavior. These stages range from the internal representations that provide our model of the world, to the later tagging of a sensation as “pleasant,” “unpleasant,” or “neutral.” From the Buddhist point of view, all of these stages, even the contact point of the external stimuli with the sensory organ's receptors, are already imprinted by an individual’s prior experience, survival patterns, and attentional priorities. Thus, one’s range of choices is constrained by many constrictions that begin in the earliest stages of sensory processing. Buddhism Suggests Mindfulness Practice as a Way of Retuning If sensory tuning constrains our choices and sense of freedom, how can we remove these constraints? Buddhism suggests mindfulness practice as a form of perceptual therapy that deconditions normal human perception (Shulman, 2010). Thus, by focusing our attention/ 14 awareness non-judgmentally on the subtle workings of the senses, we can let go of the effect that individual tuning patterns have on our choices and consequently increase our sense of freedom. This chapter's title, “Removing the Constraints on Our Choices,” has a deeper meaning in the Buddhist view, which does not consider the removal of a problem as the way to alleviate it. In fact, Buddhists view “problem” as a label that in itself imposes a constraint. Furthermore, a “problem” does not necessarily require a “solution.” Rather, understanding the constraint and its nature – accepting it and letting go of the need to either grasp or reject it – is what enables changing the constraint to a restraint4 (Goldstein, 1987). Thus, in keeping with the tuning framework described here, we can say that mindfulness practice actually “retunes” rather than “removes” constraints. It is also important to note that occupational therapists suggest that understanding individual sensory tuning patterns can help inform people about the nature of their humanity. Dunn states that “in knowing [our own] ‘features’ we might be set free to learn, evolve, and live a satisfying life. I believe that the essential gift of our sensory processing knowledge is in providing opportunities for insight” (italics added for emphasis; Dunn, 2001, p. 617). Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to review the various occupational therapy techniques, it seems that the “retuning” in occupational therapy occurs via the interaction between the therapist and the patient, and less through self-guided mental training. Biological Correlates of the Retuning Process What are the biological correlates of the retuning processes that occur through mindfulness training? Neuroscientific evidence regarding the anatomical and functional connectivity patterns in the brain is accumulating and with it comes a deeper understanding of how various brain areas can modulate and influence each other through complex 15 interconnections. The reactivity in each brain area arises from a delicate balance between local and global, excitatory and inhibitory neuronal influences (Dani et al., 2005). Highly connected areas in the brain, considered poly-modal because of their integrative nature, receive a wide range of sensory, motor, and emotional input that enables them to modulate behavior through motor and visceral outputs and by direct modulation of the sensory systems (Honey et al., 2007; Mesulam, 2008; Pessoa, 2008). Examples of such polymodal nodes are the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), an area involved in emotion regulation and modification of reactions to aversive stimuli, and the insula, an area involved in interoception and awareness of bodily sensations (Kringelbach, 2005; Pessoa, 2008). Interestingly, contemplative neuroscience, a rapidly growing field concerned with the effects of mindfulness practice on the brain, has found that these poly-modal areas (Hölzel et al., 2008; Lazar et al., 2005; Luders et al., 2009) are among a number of brain regions affected by this form of training. Other areas affected by mindfulness training include the frontal cortex (involved in integrating emotion and cognition) and sensory cortices (Lazar et al., 2005). In other words, key players in modulation processes that can affect the very first stages of sensory processing have been found to respond to mindfulness training. Recently, Kilpatrick et al. (2011) demonstrated that an eight-week MBSR course induced changes in intrinsic connectivity networks comprising parts of the sensory cortices and parts of the insula. These findings may reflect the consistent attentional focus, enhanced sensory processing, and reflective awareness of sensory experience often found following MBSR training (Kilpatrick, 2011). In sum, both sensory cortices and areas involved in modulation of sensory processes are affected by mindfulness practices. Remarkably, these neuroscience findings support the Buddhist view, over two thousand years old, regarding the relation of mindfulness to sensory processes. 16 Discussion of the Term “Coupling” and Biological Correlates of Decoupling The tuning of the sensory processes, as well as the way they are coupled to other processes, affects choices and behavior. From occupational therapy, we learned that individuals can differ in the strength of this coupling, as Dunn and her colleagues demonstrated by showing that people can have different thresholds for sensory stimuli and can also differ in the amount of regulation they apply to those stimuli. In Buddhism, this coupling is reflected in the paticcasamuppada model, whereby each link is conditioned by the link before it and conditions the link after it. In a larger sense, the workings of the sensory systems (the first half of the model) condition our cravings, actions, and self-definition (the second half of the model), thus coupling them together. By paying mindful attention to the various types of conditioning, a “decoupling” or “loosening of coupling” can occur. For example, following such decoupling, the activation of the sensory process need not activate processes related to cravings, actions, and self-definition. In support of this view, a recent study showed that Zen mindfulness practitioners report lower levels of pain in response to a thermal pain stimulus (Grant et al., 2011). The neuroscientific findings showed a functional decoupling between sensory brain areas and brain areas that play a role in cognitive evaluation of sensations. This decoupling was suggested to reflect the reports of mindfulness practitioners that the practice enables them a more neutral view of sensory painful stimuli (Grant et al., 2011). Expanding the Framework Beyond the Sensory System It is important to note that although this chapter has focused mainly on the sensory system, similar claims can be made regarding the effects of mindfulness on other basic 17 neurological systems. For instance, emotional processes are described in the paticca-samuppada and are considered a target for mindfulness practice in the Sati-pattana-suta. Indeed, emotionrelated areas such as the amygdala have been found to display a range of reactivity patterns—and thus different “tuning”—for different individuals (Hariri, 2009). Moreover, mindfulness practice has been shown to affect emotion-regulation processes (Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009). Although similar evidence can be brought forth for other brain processes (e.g., action processes), a complete review is beyond the scope of this chapter. In sum, we have attempted to understand the biological correlates of the first-person phenomenological experience of an increased sense of freedom following mindfulness practices. We used the terms tuning and coupling to integrate Buddhist phenomenological insights, observations from occupational therapy, and empirical evidence to show that individual tuning and coupling patterns impose limitations on an individual’s range of choices and that these concepts are grounded in neurobiology findings. These biological limits can be retuned and decoupled by mindfulness practices, leading to loosened constraints and increased ranges of perception, choices, and action. We hope that such integrations can benefit future research aimed at linking biology with phenomenology. 18 Footnotes 1. Paticca means “because of” or “dependent upon”; Samuppada means “arising” or “origination.” Paticca Samuppada, therefore, literally means “dependent arising” or “dependent origination,” a central concept in Buddhist philosophy. 2. Mindfulness is the most common translation of the Pali word sati. The Sati Patthana sutta or “The four foundations of mindfulness” is one of the earliest instructions for mindfulness practice, in which the Buddha teaches his disciples to be mindful and attentive to the activities of the body [kaya], the sensations or feelings [vedana], the activities of the mind [citta], and to ideas, thoughts, conceptions, and things [dhamma]. 3. The sixth “sense-base” here refers to thoughts, which are considered to be one of the foci of a sense in Buddhism. 4. An even deeper understanding in Buddhism is that the concept of a separate and constant self is illusionary. The letting go of the very concept of self is the deepest practice in Buddhism, and also in mindfulness meditation. If not overcome, this construct of separateness will cause innumerable problems. 19 Figure Legends Figure 1. Paticca Samuppada cycle – a circular model representing a chain of conditioned arising of suffering, each cause (each link) being conditioned by the preceding link as well as actively conditioning the following link. The links in Pali begin with “lack of self awareness” and continue in clockwise order: avijja, sankhara, vinnana, nama-rupa, salayatana, phassa, vedana, upadana, bhava, jati, jara-marana, and dukkha. References Aran, L. (1993). Buddhism. Tel Aviv: Dvir. Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (1997). Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 345–368. Baranek, G. T., Foster, L. G., & Berkson, G. (1997). Tactile defensiveness and stereotyped behaviors. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51, 91-95. Beck, C. J. (2000). Everyday Zen: Love and work. New York: Harper Collins. Brown, C., Tollefson, N., Dunn, W., Cromwell, R., & Filion, D. (2001). The Adult Sensory Profile: Measuring patterns of sensory processing. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55, 75–82. Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 560-572. Dani, V. S., Chang, Q., Maffei, A., Turrigiano, G. G., Jaenisch, R., & Nelson, S. B. (2005). Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett Syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102, 12560-12565. 20 Dunn, W. (2001). The sensations of everyday life: Theoretical, conceptual, and pragmatic considerations. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55, 608-620. Ehrhard, F. K., Fischer-Schreiber, I., & Diener, M. S. (1991). The Shambhala dictionary of Buddhism and Zen. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications, Inc. Engel-Yeger, B. (2008). Sensory processing patterns and daily activity preferences of Israeli children. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75, 220-229. Engel-Yeger, B., Stern-Ellran, K., & Levit-Binnun, N. (2011, in preparation). The relation between individual sensory profiles and temperament and attachment styles. Goldstein, J., Kornfield, J. (1987). Seeking the heart of wisdom: The path of insight meditation. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications. Grant, J. A., Courtemanche, J., & Rainville P. (2011). A non-elaborative mental stance and decoupling of executive and pain-related cortices predicts low pain sensitivity in Zen meditators. Pain, 152, 150-156. Greeson, J. M. (2009). Mindfulness research update: 2008. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14, 10-18. Hariri, A. R. (2009). The neurobiology of individual differences in complex behavioral. Traits Annual Review Neuroscience, 32, 225-247. Hölzel, B. K., Ott, U., Gard, T., Hempel, H., Weygandt, M., Morgen. K., et al. (2007a). Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxel-based morphometry. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 3, 55–61. Honey, C. J., Kotter, R., Breakspear, M., & Sporns, O. (2007). Network structure of cerebral cortex shapes functional connectivity on multiple time scales. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 10240-10245. 21 Jagiellowicz, J., Xu, X., Aron, A., Aron, E., Cao, G., Feng, T., et al. (2011) The trait of sensory processing sensitivity and neural responses to changes in visual scenes. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 6, 38-47 Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion. Kandel, E., Schwartz, J., & Jessell, T. (2000). Principles of neural science. New York: McGrawHill. Kornfield, J. (2008). The wise heart: A guide to the universal teachings of Buddhist psychology. New York: Bantam. Kringelbach, M. L., (2005). The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6, 691-702. Lazar, S.W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T., et al. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport, 16, 1893–1897. Markram, H., Rinaldi, T., & Markram, K. (2007). The intense world syndrome: An alternative hypothesis for autism. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 1, 77-96. McConnell, J. (1995). Mindful mediation: A handbook for Buddhist peacemakers. Bangkok: Buddhist Research Institute/Spirit in Education Movement/Foundation for Children. Mclntosh, D. N., Miller, L. J., Shyu, V., & Dunn, W. (1999). Overview of the short sensory profile (SSP). In W. Dunn (Ed.), The sensory profile (pp. 59-74). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. Mesulam, M. (2008). Representation, inference, and transcendent encoding in neurocognitive networks of the human brain. Annals of Neurology, 64, 367-378. 22 Paticca samuppada vibhanga Sutta: Analysis of dependent co-arising in Samyutta Nikaya 12.2; ii, 2. [Electronic version]. http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn12/sn12.002.than.html Pelled, A. (2007). Raising goodness all around: Buddhism, meditation, psychotherapy. Tel Aviv: Resling. Pessoa, L. (2008). On the relationship between emotion and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9, 148-158. Mikulas, W. L. (2007). Buddhism and western psychology: Fundamentals of integration. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 14, 4-49. Slagter, H. A., Lutz, A., Greischar, L. L., Francis, A.D., Nieuwenhuis, S., Davis, J., et al. (2007). Mental training affects distribution of limited brain resources. PLoS Biology, 5, e138. Rahula, W. (1959). What the Buddha taught. New York: Gove/Atlantic. Sati Patthana Sutta: The foundations of mindfulness in MAjjhima Nikaya 10; i, 55. [Electronic version]. From http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/ mn/mn.010.nysa.html Sverdlik, N., & Levit-Binnun, N. (2011, in preparation). Can individual sensory profiles predict individual personal values? Thera, N. The power of mindfulness: An inquiry into the scope of bare attention and the principal sources of its strength. [Electronic version]. From http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/nyanaponika/wheel121.html 23

![[SENSORY LANGUAGE WRITING TOOL]](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/014348242_1-6458abd974b03da267bcaa1c7b2177cc-150x150.png)