* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Overview of Protein Structure • The three

Signal transduction wikipedia , lookup

Paracrine signalling wikipedia , lookup

Amino acid synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

Peptide synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Biosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

Genetic code wikipedia , lookup

Ancestral sequence reconstruction wikipedia , lookup

Expression vector wikipedia , lookup

Magnesium transporter wikipedia , lookup

G protein–coupled receptor wikipedia , lookup

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation wikipedia , lookup

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides wikipedia , lookup

Interactome wikipedia , lookup

Protein purification wikipedia , lookup

Metalloprotein wikipedia , lookup

Homology modeling wikipedia , lookup

Western blot wikipedia , lookup

Biochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Two-hybrid screening wikipedia , lookup

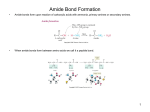

Intro to Protein Structure, p. 1 BCMP201, 2001 Overview of Protein Structure General References Stryer, L. 1995. Protein Structure and Function. Chapter 2 in Biochemistry, fourth ed. (W.H. Freeman, New York). Branden, C. and Tooze, J. 1991. Chapters 1 and 2, pp. 1-31 in Introduction to Protein Structure. (Garland Publishing, New York). Creighton T.E. 1994. Physical Interactions that Determine the Properties of Proteins. Chapter 4, pp. 139-165 in Proteins, 2nd edition. (W.H. Freeman, New York). Creighton T.E. 1994. Conformational Properties of Polypeptide Chains. Chapter 5, . pp. 171-1196 in Proteins, 2nd edition. (W.H. Freeman, New York). Creighton T.E. 1994. Proteins in Solution and in Membranes. Chapter 7, pp. 261-325 in Proteins, 2nd edition. (W.H. Freeman, New York). • The three-dimensional structures of small molecules are reasonably well defined by their covalent bonding arrangement. Proteins and other macromolecules have markedly greater conformational freedom by virtue of their large size and chemical complexity. Rotation about single bonds in a polypeptide chain generates a vast number of potential alternative conformations. Proteins are unusual among chemical polymers in that they adopt one folded conformation in solution. Steric repulsion between neighboring amino acids partially restricts the number of conformations accessible to a peptide chain. Weak noncovalent interactions among neighboring residues in the folded state determine the native conformation. However, not all protein segments are stably folded under physiological conditions; flexion or movement of certain regions may play a role in protein-protein interactions, the generation of force, or in serving as an on-and-off switch for a protein’s function. • We will first examine the chemical properties of polypeptides, emphasizing those features contributing to their folded structure. The chemical parameters dictating native structure are complex and poorly understood. Further insight into the “protein folding problem” can be gained by studying the diversity of amino acid sequences present in families of structurally homologous proteins, in order to identify the absolute sequence requirements for a given peptide fold. These efforts have led to improved methods of predicting the native structures of peptides and proteins. Intro to Protein Structure, p. 2 BCMP201, 2001 Amino Acids and the Peptide Bond: • The peptide bond is a key determinant of protein structure- Polypeptides are formed by a ribosome-catalyzed condensation of amino acids, creating a linear chain with restricted flexibility. The main chain atoms N, Cα, C and O, are common to all amino acids and these form the 'backbone', or main chain, of the peptide. Peptide bonds join neighboring residues in a head-to-tail arrangement. These connections between amino acids are rigid because of an electronic resonance that imparts partial double bond character to the peptide bond. • Most peptide bonds are in the trans configuration- Consequently, the atoms Cα-C-N'-Cα' are confined to a plane in which Cα and Cα' may be in either a cis- or a trans- orientation with respect to the peptide bond. Trans- peptide bonds are generally preferred, probably because of fewer steric clashes between the side chain atoms of neighboring residues. However, cis- peptide bonds are allowed amino-terminal to proline residues, owing to the unique cyclic side chain of proline (see below). Another consequence of peptide bond resonance is the polarization of the amide nitrogen and the carboxyl oxygen, creating a very good hydrogen bond donor and acceptor, respectively. Hydrogen bonds between these main chain atoms are a prominent feature of many secondary structural motifs. • Amino acids are chiral compounds- The peptide main chain is decorated with side chains that are specified by the amino acid sequence. Each constellation of side chains confers unique physicochemical properties to a given peptide sequence. All amino acids except glycine have a chiral center located at Cα. Naturally occurring amino acids are L-enantiomers, and this choice of hand defines the region of conformational space that is accessible to a peptide chain. Proteins of identical sequence consisting either of all L-amino acids or of all D-amino acids would be unable to adopt the same structure because of stereospecific differences in the potential clashes between neighboring residues. Intro to Protein Structure, p. 3 BCMP201, 2001 • Polypeptide conformation- Two dihedral angles, φ (phi) and ψ (psi), define the course of the peptide chain. The φ angle designates rotation about the bond joining N to Cα, and ψ designates rotation about the Cα-C bond. Rotation about these bonds causes crankshaft-like motions that alter the course of the peptide chain, generating regular conformations like the β-strand, reverse turns, and α-helices. The side chain attached to Cα of each amino acid limits rotation about φ and ψ because of steric hindrance between the side chain and the adjacent main chain atoms. Glycine lacks a side chain and is therefore more flexible than other amino acids. Thus, glycine is prevalent in turns, loops, and other flexible segments of proteins. Regular secondary structures such as the α helix or the β-strand have characteristic φ and ψ angles. • The conformational space, or range of φ and ψ angles, of the residues within a protein can be displayed on a Ramachandran plot (named for the biophysicist G.N. Ramachandran). Highly populated areas on the Ramachandran plot correspond to residues within segments of regular secondary structure (helices, sheets). Most of the remaining area of conformational space is forbidden to all residues except glycine, because of steric clashes that would result from the main chain adopting these dihedral angles. Intro to Protein Structure, p. 4 BCMP201, 2001 Intro to Protein Structure, p. 5 BCMP201, 2001 Amino Acid Side Chains • The 20 naturally occurring amino acids can be classified according to the properties of their side chains. The side chain determines how a residue interacts with its neighbors and, to some degree, whether it is likely to be located near the surface or buried within the protein fold. • Aliphatic amino acids (A,V,L,I,M,P)- Hydrophobic amino acids dominate in the protein interior. These are the most structurally diverse group of residues, reflecting their role in filling the irregular spaces within the protein core. Intro to Protein Structure, p. 6 BCMP201, 2001 • Aromatic amino acids (F, Y, and W)- Aromatic rings participate in π-electron stacking interactions with one another and with ligands. The aromatic residues tyrosine and tryptophan, and to a lessor extent phenylalanine, account for most of the near-UV range absorbance and fluorescence properties of proteins. The spectral properties of these residues are strongly influenced by the local environment of the aromatic ring, making them useful probes of protein structure. • Polar amino acids (S, T, N, Q, and H)- Polar residues contain oxygen and/or nitrogen atoms that participate in hydrogen bonds that stabilize various protein folds, assist chemical reactions, or participate in the recognition of other molecules. The imidazole ring of histidine is a very effective nucleophilic catalyst that is present in a number of enzyme active sites, including the catalytic triad of the serine. Histidine is partially charged at physiological pH (pKa ≅ 6.2). Intro to Protein Structure, p. 7 BCMP201, 2001 • Charged amino acids (D, E, K, and R)- these are typically located on the surface of proteins, where they participate in long-range electrostatic interactions between protein subunits, or contacts with substrates and other ligands. Examples include the active site aspartic acid in acid proteases (pepsin) and the basic residues of DNA-binding domains. • Glycine- Glycine lacks a side chain and is therefore achiral, being less sterically encumbered than the other residues. Glycine can readily adopt conformations that are forbidden for other amino acids, allowing irregular structures such as loops and turns at the protein surface. • Proline, a special case - Proline is an imino acid with a side chain that forms a 5-membered pyrrolidine ring. This severely restricts the range of the main chain dihedral angle φ and, consequently, proline is greatly disfavored in certain secondary structures such as the α-helix. Prolines are typically Intro to Protein Structure, p. 8 BCMP201, 2001 found in loops and extend segments of the peptide chain. • Cysteine and disulfide bonds- Cysteine is a polar amino acid that is readily deprotonated, forming a highly reactive thiolate ion that can covalently bond with alkylhalides, heavy metals, or other cysteines. A covalent link between 2 cysteine sulfurs is termed a disulfide bond. Disulfide bonds stabilize protein secondary structure by crosslinking cysteine residues that are distant in the primary sequence. Disulfide bonds are found in hormones (insulin), toxins, and some thermostabile proteins. • Rotamers- Side chain conformations are described by the torsion angles χ1χ2, χ3 , etc. Energeticallyfavored conformations, termed side chain rotamers, have χ1 andχ2 angles of approximately -60 (g+), +60 (g-), or 180 degrees. Most amino acids in high-resolution protein models conform to one of the preferred rotamers. Levels of Protein Structure • Primary Structure - A protein's amino acid sequence determines its unique three-dimensional structure. In general, proteins with homologous primary sequences adopt similar folds. However, the amount of sequence relatedness that assures two proteins have homologous structures is difficult to predict, and localized differences in structure can have important functional consequences. This means that predictions of protein structure that are based on primary sequence data are tentative at best. • Secondary Structure - Polypeptide chains fold into compact shapes that exclude water from the protein interior. Segments of the peptide chain assume regular, repeating shapes that are determined by favorable interactions between adjacent residues. These local packing arrangements typically involve short (5 to 20 residues) segments and they are termed secondary structures. Common secondary structures include α-helices, β-strands, and reverse turns. These structures are stabilized by repeating patterns of hydrogen bonds between main chain oxygens and nitrogens. • Tertiary and Quaternary Structure - Elements of secondary structure pack together in folded proteins, bringing residues that are distal in the primary sequence into close proximity. Packing Intro to Protein Structure, p. 9 BCMP201, 2001 arrangements that involve segments of a single polypeptide chain are termed tertiary structure. Some proteins aggregate, forming oligomers such as dimers, trimers, etc. Quaternary structure describes the arrangement of subunits in oligomeric proteins. • Larger proteins consist of discrete modules of structure, termed domains, that are connected by extended segments. In many cases, this “beads on a string” modular architecture also corresponds to discrete functional modules. An example of this is the Src protein kinase (right). Principles of Protein Folds • The interior of proteins is hydrophobic, consisting primarily of aliphatic residues that are in intimate contact so as to exclude water. It is thought that exclusion of water from the hydrophobic protein interior is one of the principle forces stabilizing the native structure of proteins. However, this places the polar nitrogen and oxygen atoms of the protein main chain in a very hydrophobic environment in which their hydrogen bonding potential must be satisfied. This problem has been solved by proteins folding into regular, repeating secondary structures in which (almost) all main chain nitrogens and oxygens participate in hydrogen bonds. Residues with charged or polar side chains are typically located on the protein surface, where they participate in electrostatic interactions between neighboring domains, in the binding of small ligands or in the recognition of other macromolecules. Examples of Protein Secondary Structure • α-Helices and helical bundles- The α-helix is one of the most common secondary structures. The hand and pitch of an α-helix are determined by a repeating pattern of main chain dihedral angles (approx. φ ≅ -60, ψ ≅ -40) that generate a regular helix. α-helices are right-handed, with about 3.6 residues per turn. This helical pitch means that residues along one face of the helix are located 3 to 4 residues apart in primary sequence. Some amino acids tend to be excluded from α-helices. Prolines disrupt helices because they cannot adopt the preferred main chain dihedral angles, and because the amide nitrogen is not available for hydrogen bonding with a nearby carbonyl (see below). Glycine tends to destabilize α-helices because its conformation is less constrained and therefore less likely to adopt the necessary backbone conformation. Intro to Protein Structure, p. 10 BCMP201, 2001 • • α-Helices are rigid, rod-like structures that are stabilized by a 'web' of hydrogen bonds between the main chain amide nitrogens and carboxyl oxygens in adjacent turns of the helix. The carbonyl oxygen of residue 'i' accepts a hydrogen bond from the amide nitrogen of residue 'i+4'. The dipoles associated with these intrahelical hydrogen bonds are aligned, giving rise to a helix macrodipole with a partial positive charge at the amino-terminus and a partial negative charge at the carboxyl-terminus of the helix. Helix macrodipoles strongly contribute to the overall dipole moment of proteins and, in some instances, this effect may guide or stabilize the interaction of proteins with charged molecules. For example, the dipole moment of the 'recognition helix' of certain DNA-binding proteins is thought to contribute to the stability of the protein-DNA complex. • α-Helices are stabilized by a web of intrahelical hydrogen bonds between carbonyl oxygens and the amide nitrogens of the residue located 4 residues (one turn) towards the C-terminus of the helix. • Many helices are amphipathic; that is, they have a hydrophobic face and a hydrophilic face. This amphipathic character facilitates packing against the hydrophobic protein interior while exposing the opposite face of the helix to solvent. Helices may pack together, forming 2-, 3-, or 4-helix bundles that are typically quite stabile and inflexible. Helical bundles are commonly seen at interfaces between protein subunits, or in the filamentous proteins forming the cytoskeleton and other cellular structures. Hydrophobic side chains facing the interior of the helical bundle pack tightly together, excluding water from the interior of the folded protein. Additional stability is gained from hydrogen bonds and salt bridges that link helices at the protein surface. β-sheets- Another very common protein secondary structure is the β-sheet, which consists of a group of Intro to Protein Structure, p. 11 BCMP201, 2001 extended polypeptide chains termed β-strands. β-sheets are either parallel or anti-parallel, depending on the orientation of adjacent strands. Both types of β-sheet are stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the main chain atoms of adjacent strands, with all interior hydrogen bond donors and acceptors participating in this network. In parallel sheets, all β-strands are oriented in the same N-terminal to C-terminal direction. In anti-parallel sheets, adjacent strands have opposite polarities and the hydrogen bonds connecting adjacent strands show an alternating pattern of wide and narrow spacing. The normal packing arrangement between the strands of a β-sheet creates a slight right-handed curvature. Unlike α-helices, β-sheets consist of peptide segments that may be distal in primary sequence, with the residues connecting the strands comprising loops or other secondary structures. • Loops and turns- Loops and turns connect the more regular elements of secondary structure. Reverse turns are compact structures in which the peptide chain doubles back on itself, reversing the direction of the main chain. Reverse turns are stabilized by hydrogen bonds bridging across the interior of the turn. Loops are typically located on the protein surface and they include many of a protein's antigenic epitopes. Loops and turns also serve as flexible hinges that allow movements between and within protein domains. Examples of Tertiary Structure - Motifs and Domains • Motifs- Elements of secondary structure combine into simple folds termed motifs, which consist of a limited number of α-helices and/or β-sheets and the intervening peptide segments. Examples of motifs include the helix-turn-helix and the β-hairpin. • Domains- A domain consists of several motifs packed in a specific, compact arrangement that in many cases can fold as an independent unit. Small proteins may consist of a single domain, whereas larger proteins typically consist of multiple domains connected by flexible segments of the peptide chain. Domains are characteristically resistant to proteases, whereas the loops and strands connecting these domains tend to be exposed and protease-sensitive. This feature can be exploited by cleaving a protein into its constituent domains by limited proteolysis. In many cases, these isolated domains retain some of the functions of the parent protein. For example, DNA-binding domains of many transcription factors are independent modules that can be combined with other domains (such as a transcriptional activation Intro to Protein Structure, p. 12 BCMP201, 2001 domain) to create chimeric proteins with unique properties. This functional modularity is a direct consequence of protein domain structure. Intro to Protein Structure, p. 13 BCMP201, 2001 Examples - simple motifs include the Greek key, which is a common topology linking the strands of βsheets. The EF-hand motif (center) is a calcium-binding site formed at the junction of 2 α-helices. The metal atom is chelated by acidic side chains and nearby main chain atoms. α-Helical coiled-coils provide rigidity to structural proteins and to dimeric transcription factors like the basic region leucine zipper proteins. Forces Stabilizing the Native Folds of Proteins • Genetic information is ultimately expressed in the production of proteins having unique activities and structures that are specified by a particular amino acid sequence. How this linear genetic code is converted into a precise three-dimensional protein structure remains one of the outstanding questions of molecular biology, commonly known as the 'protein folding problem'. • Proteins are only marginally stable at physiological temperature, and they are held together by a number of weak, interdependent forces. The thermodynamic hypothesis of protein stability states that the native conformation of a protein is thermodynamically the most stable conformation that a polypeptide chain can assume. Therefore, the native conformation should not depend upon the particular folding pathway to the native state nor require the presence of accessory proteins to guide the folding process (molecular chaperones). The thermodynamic hypothesis also predicts that protein folding should be spontaneous and reversible. These properties are not always observed experimentally; some proteins require molecular chaperones to accelerate the folding rate to a biologically relevant time scale. Weak, Noncovalent Interactions: • Dispersion Forces - (0.01 - 0.2 kcal/mol) van der Waals interactions are isotropic (nondirectional) and very weak. However, they are numerous and therefore are a major contributor to protein stability. Intro to Protein Structure, p. 14 BCMP201, 2001 Electrostatic Interactions • Salt Bridges- (1-5 kcal/mol) weaker, long-range forces. Charged residues participating in salt bridges are almost always at the protein surface. The strength of these interactions is influenced by pH, ionic strength, and the local electrostatic environment. • Hydrogen Bonds - (2 - 10 kcal/mol) Hydrogen bonds are directional and therefore well suited for specifying particular interactions. Side chains and main chain atoms participate in numerous hydrogen bonds at the surface and in the interior of proteins. Examples include hydrogen bonds between the turns of an αhelix or joining the strands of β-sheets. Covalent Interactions • Disulfide Bonds - Covalent bonds between two cysteine sulfur atoms, termed disulfide bonds, are found in many proteins. These disulfide bridges form spontaneously between specific cysteine pairs, even under the reducing conditions within the cell. Disulfide bonds provide added structural stability and many are involved in specific functions. Although they are rare in comparison to the interactions Intro to Protein Structure, p. 15 BCMP201, 2001 discussed above, disulfide bonds are more abundant in proteins functioning in extracellular spaces, such as digestive enzymes and peptide hormones. Intro to Protein Structure, p. 16 BCMP201, 2001 • The hydrophobic effect- Arguably, the most important force stabilizing protein structure is the hydrophobic force. It can be described as the aversion of aliphatic residues for the aqueous environment of the cell, which causes hydrophobic residues to cluster within the interior of the folded protein. Although the physical basis of the hydrophobic effect is complex, a striking feature (at physiological temperatures) is the formation of ordered 'cages' of water around hydrophobic surfaces, such as those of an unfolded polypeptide. The internalization of hydrophobic groups during protein folding releases caged water, resulting in an entropy change that favors protein folding. Proteins generally fold into compact shapes that exclude water from their interior. Typically, the van der Waals radii of the atoms within a protein occupy 70% to 80% of a its volume. Thus, residues are very tightly packed against one another in the protein interior. • Events in protein folding- The acquisition of native structure is a highly cooperative process, which approximates a two-state equilibrium between the unfolded and native conformations. Recent improvements in proton exchange nuclear magnetic resonance techniques, and stopped flow circular dichroism methodologies, as well as the development of peptide models of protein folding, have allowed the characterization of partially-folded intermediates in the folding pathways of several proteins. These studies suggest that different segments of the polypeptide chain fold independently and at different rates, creating several regions of transient secondary structure. Folding culminates with a coalescence of partially structured folding intermediates, creating the final native structure. The thermodynamic hypothesis of protein stability postulates that the native structure is the most stable conformation and it is not dependent on the particular pathway to the native state. Recent experimental evidence suggests that a given protein may use several distinct folding pathways to achieve native conformation. This mechanistic plurality may arise from conformational heterogeneity of the unfolded polypeptide. Most large proteins do not spontaneously fold on an experimentally observable time scale. These proteins require the assistance of molecular chaperones, which guide the proper folding of proteins and multi-protein complexes. The chaperones themselves assemble into oligomeric ribosome-sized, ring-shaped structures that interact transiently with partially folded or denatured proteins, apparently without regard to the amino acid sequence of the peptide chain. We will return to this topic later in the course.