* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The ecological citizen and climate change

Soon and Baliunas controversy wikipedia , lookup

Climatic Research Unit email controversy wikipedia , lookup

Global warming controversy wikipedia , lookup

German Climate Action Plan 2050 wikipedia , lookup

Economics of climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Climatic Research Unit documents wikipedia , lookup

Heaven and Earth (book) wikipedia , lookup

Fred Singer wikipedia , lookup

General circulation model wikipedia , lookup

Global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change feedback wikipedia , lookup

2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference wikipedia , lookup

Climate sensitivity wikipedia , lookup

ExxonMobil climate change controversy wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on human health wikipedia , lookup

Climate resilience wikipedia , lookup

Climate change denial wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Saskatchewan wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Australia wikipedia , lookup

Attribution of recent climate change wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Politics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Tuvalu wikipedia , lookup

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Climate change adaptation wikipedia , lookup

Economics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Media coverage of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme wikipedia , lookup

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

Climate change, industry and society wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

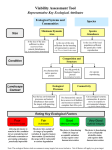

The ecological citizen and climate change Johanna Wolf Prepared for the workshop “Democracy on the day after tomorrow” at the ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research School of Environmental Sciences University of East Anglia Norwich, UK Abstract To date, most research on climate change has focused on the science of possible impacts and the formulation of international policy responses. In comparison, relatively few studies have considered the social mechanisms and processes by which responses to climate change could occur. This paper examines participants’ responses to climate change based on two case studies on Canada’s west coast. It argues that ecological citizenship provides significant explanatory power for the accounts of participants. The results suggest that participants feel a responsibility for their incremental contributions to climate change which they describe as a civic duty that is owed to those currently affected by impacts and to future generations. The responsibility matches what has been described as ecological citizenship because it is felt to be a nonreciprocal, non-territorial, responsibility-focussed commitment of the private sphere. The findings suggest that with respect to climate change, individuals’ actions and underlying attitudes are concerned with current and future implications of northern living standards and lifestyles, are driven by a sense of individual civic responsibility, and seek agency beyond that afforded by the state. The ecological citizen and climate change 1 Citizens and the environment [E]mergent ecological concerns have added fuel to a complex debate about the responsibilities that attach to citizenship (Dean 2001). With rising environmental concerns over the past decades, and politically contested approaches to remediating them, political aspects of citizens’ lives have not been unaffected. This is reflected also in a to date largely theoretical debate that has begun to explore the possible linkages between citizenship and the environment. Of many global problems, global climate change is often cited as the most serious threat facing humanity today. Projections indicate that climate change will impact societies and ecosystems throughout and beyond the 21st century. The impacts of climate change will affect all countries and regions around the world, albeit in different and uncertain ways. Developed countries have contributed the majority of historic emissions since the industrial revolution whilst, it has been argued, developing countries are most vulnerable to the impacts, amplified by their socio-economic vulnerabilities. Therefore, climate change is a problem of equity, caused by past emissions and borne by those who have contributed least, developing countries and generations not yet born. This paper argues that ecological citizenship has significant explanatory power in a case study setting in Canada, where intergenerational equity, among other factors, is a motivation for the ecological citizen to act to reduce individual contributions to climate change. 1.1 Characteristics of ecological citizenship Research considering citizenship and the environment by Christoff (1996), Smith (1998) and Barry (1999b; 2002) demonstrates the relevance of environmental problems to citizenship theory. This has paved the way for Dobson (2003) to highlight the importance of the at least normative connection between citizenship theory and the environment. There are only very few empirical applications of ecological citizenship. For example, Horton (2005) found in a case study of environmental activists in the UK that green citizenship is produced by and practiced within a green socio-cultural architecture in which cultural institutions promote the routinized performance of green identities (p. 145). This section introduces the key characteristics of ecological citizenship based on theory: the ways in which it extends beyond liberal and civicECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 2 The ecological citizen and climate change republican citizenship, its concern with civic responsibilities rather than rights, and its concern with fairness and equity. Ecological citizenship as suggested by Dobson (2003) is a development of what he calls post-cosmopolitan citizenship. Both citizenship types extend beyond the remits of liberal and civic-republican citizenship types in four ways. This paper focuses on ecological citizenship. First, it shares the language of virtues with civic-republican citizenship; its principal virtue is justice (ibid., p. 132). Second, its obligations are owed non- reciprocally. Third, its remit includes not only the public but also the private sphere. And fourth, ecological citizenship extends beyond the boundaries of the state (ibid., p. 82). These four hallmarks of ecological citizenship are important features used in this research to examine empirical data in section 3 below. An underlying principle of ecological citizenship is that of fairness. By implying justice as the prime virtue of ecological citizenship, and considering further virtues such as care and compassion (p. 67), Dobson expands the concept of citizenship into realms that have previously been argued to belong not to the ‘good citizen’ but to the ‘Good Samaritan’. Yet, the origins of the virtues are the relationships that give rise to the obligations of citizenship in the first place, and it is the relationships, not the virtues themselves, that give rise to citizenship obligations (ibid., p. 66). With this in mind, these relationships are of a historical nature as they arise from what Lichtenberg (1981) calls “antecedent action, undertaking, agreement…” between strangers (in Dobson 2003). It is clear from this that the type of fairness implied here is about intergenerational as much as intragenerational equity. The origin of both of these aspects of equity lies in “identifiable relations of actual harm” (Dobson 2003, p. 81), that is the (collective) consequences of actions undertaken in the past and today, now and in the future. At the core of ecological citizenship is also a recognition of obligations and responsibilities as central tenets, rather than rights as in liberal citizenship thinking (Dobson 2003). This relates to the point above about fairness and poses the question to whom these obligations or duties are owed. Temporal and geographic boundaries that previously have confined the consequences of individuals’ actions have been dispelled by the effects of globalisation to augment the reach of private agents’ remits to the future and the global – albeit primarily in developed countries. This relates to the inclusion of the private sphere in post-cosmopolitan citizenship because unequivocally, private acts, such as driving a car, can have public implications (cf. e.g. Clarke 1999), such as ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 3 The ecological citizen and climate change contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. Arguably, such private acts are inextricably intertwined with living standards (access to and ownership of a car) and lifestyles (the choice to drive), which in turn are tied to the level of economic development in a location or state. Ecological citizenship therefore bears a civic concern for the implications of individual actions. What, however, is the link between ecological citizenship and climate change? The next section offers an answer to this question. 1.2 Ecological citizenship and climate change It has been argued that both post-cosmopolitan and ecological citizenship are concerned with bone fide citizenly activities (Dobson 2003). Based on this, the purpose of this section is to outline the connection between the theoretical dimensions of ecological citizenship offered by Dobson and the specific characteristics of climate change as a social problem, that is, how it is caused and may be responded to. Non-territoriality is an important dimension of ecological citizenship, and it is a key characteristic that links this citizenship to climate change (and indeed other global environmental problems). It is ubiquitously agreed that climate change constitutes a global problem because it is caused by, affects, and cannot be remediated without the participation of a multitude of global actors (Watson 2001). The global nature of the causes of the issue also implies that national boundaries, the traditional realm of citizenship operation, are merely another obstacle to effective action on the problem, as demonstrated by the lack of international cooperation on the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol by the world’s most significant emitter, the United States. The impacts of climate change are unequally distributed across geographic space and in time, and they do not respect national boundaries, impacting those that are most vulnerable (Adger et al. 2006). Just as the impacts of globalisation are asymmetric between developed and developing countries, so do the obligations of ecological citizenship arise from the asymmetric distribution of power and effect between (and among) citizens of developed and developing countries. This is mirrored also in Goodall (1994) who suggests that only many individual acts at the local level will bring about significant change. As a result, national boundaries aside, all those citizens who participate in activities that contribute to climate change bear obligations to reduce their share in causing the problem. Theoretically, it can be argued, they also bear a share of responsibility for whatever damage and subsequent remediation arises from the impacts of climate change. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 4 The ecological citizen and climate change Dobson (2003) suggests that the duties and responsibilities of ecological citizenship arise from the impact (“ecological footprint”, p. 118) individual citizen’s activities have on the opportunities of other citizens within or outside the same country. Closely aligned with Brundtland’s definition of sustainability (WCED 1987), he thus proposes that the key obligation of the ecological citizen is to ensure that the impact of an individual fulfilling his or her needs does not foreclose the ability of others, alive now and in the future, to pursue their needs. Effectively, ecological citizenship as proposed here follows from the non-territorial consequences of lives lived in developed countries and is an instantiation of sustainability. The link to climate change then is straightforward: as incremental as an individual’s contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions may be, it still adds to the overall plight borne by future generations and those people who are vulnerable to the consequences of climate change. Because citizens in developed countries have contributed and continue to emit the overwhelming majority of historic GHG emissions, it is these citizens who are mainly responsible for current climate change. Considering the impacts of climate change on common resources, such as limited freshwater supplies, an individual’s overuse of water affects those tapping into the same resource, now or later, and forecloses adaptation options now and potentially in the future. This is an example of the relationship between strangers mentioned above that gives rise to citizenship obligations. Following Lichtenberg (1981), these are citizenly obligations because the emissions individuals contribute are at least part of the causes of global climate change, and this causal relation between strangers is what rules out moral commitments in this instance1. Virtues are central to ecological citizenship for two reasons. First, the ecological citizen has an obligation to ensure that his or her impact does not foreclose the opportunities of others. Second, an underlying theme of ecological citizenship identified in section 1.1 above is fairness, between citizens of developed and developing countries and citizens now and in the future. From this, it is clear why Dobson posits that the first virtue of ecological citizenship is justice (Dobson 2003). “Ecological citizens care because they want to do justice” (ibid., p. 123). This virtue, albeit not necessarily of individuals, also 1 This does not preclude that reducing individual emissions cannot be inherently right. The argument here, however, focuses on the nature of the link between individuals, which, if there is a cause and effect relationship between individuals’ actions, is citizenly. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 5 The ecological citizen and climate change plays a crucial role in adaptation to climate change (Adger 2001; Smit and Pilifosova 2001; Adger and Paavola 2002; Thomas and Twyman 2005; Adger et al. 2006). Virtues important in effecting justice could include some that are more commonly associated with being a ‘good person’ rather than a ‘good citizen’, compassion and care. As shown earlier, ecological citizenship considers the private realm as a site where citizenship activities occur. This is so because first, private actions can have public implications, and second, because the second order virtues of care and compassion are typically associated with the private realm and private relationships (Dobson 2003). Considering the first aspect, the public implications of private actions, it was already argued above that GHG emissions generated by individuals, for example, from car use, generate a responsibility of a civic nature. The second aspect, the virtues of care and compassion, can be related to considering the impacts of one’s actions on others, on future generations and strangers, that may live far from one’s own home. When the two come together, that is, a non-reciprocal care about the lives of others induced by the recognition that one’s GHG emissions contribute to the impacts of climate change on others, ecological citizenship takes on concrete shape. It is important to highlight that the obligation is of a citizenship type because of the causal link between an individual’s actions, albeit incrementally, and temporally and spatially removed, and the consequences that may occur elsewhere. Adaptation to the impacts of climate change has been defined as adjustments to perceived or anticipated climate stimuli (Smit and Pilifosova 2001). Some literature discusses adaptation to climate change impacts in a context of fairness and justice, however, this work does not consider whether, and if so how, adaptation may be linked to citizenship. In principle, adaptive responses to climate change impacts occur now and in the future, by those already affected ex post (reactive adaptation) and by those who perceive, or will perceive, a threat ex ante (anticipatory adaptation). Adaptive capacity has been identified as the “potential, capability, or ability of a system to adapt to climate change stimuli or their effects or impacts” (ibid., p. 894). When setting this into the context of individuals’ actions, equity, and citizenship, a connection emerges: Failure to recognise the consequences of one’s actions that impact others can constrain the others’ capacity to adapt to climate impacts. This is certainly expected for future generations who will need to adapt to all those impacts current generations fail to avoid through mitigation and long term adaptation. On the other hand, ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 6 The ecological citizen and climate change adaptation to impacts further afield, geographically and temporally removed from those who contribute emissions, can theoretically be hindered by the very global socioeconomic structures that create the problem in the first place. Vulnerability plays a crucial role here because by the same token, those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change are also those least able to adapt (Adger et al. 2006). Wisner et al. (2004) define vulnerability as “the characteristics of a person or group and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard”. In an incremental way, the impacts of individuals’ actions now, primarily in the North, modify and shape those characteristics, now as well as in the future. The impacts of climate change give rise to obligations of citizenship because they are brought about by private choices that generate relationships to strangers, citizens elsewhere and in the future. Thus, acting as an ecological citizen can overcome one of the constraints on adaptive responses to impacts. 1.3 Criticisms of ecological citizenship The theoretical advances by Dobson have recently sparked a debate about what enables ecological or green citizenship to be enacted (e.g. Bell 2005; Carter and Huby 2005; Drevensek 2005; Hailwood 2005; Luque 2005; Sáiz 2005; Seyfang 2005; Smith 2005; Valdivielso 2005). In critiques of Dobson’s work, two crucial weaknesses of ecological citizenship theory, and its potential application in practice, have been identified. First, as Saíz (2005) puts it, “Dobson’s insistence on the efficacy of individual political agency” (p. 176) is a critical point of weakness because it implies that individuals can be relied upon to strive to be better citizens. This ignores that individuals act within a social, economic, cultural and institutional context that shapes and constrains citizens’ ability to act in particular ways. A related point is made also by Luque (2005) who points out that the ecological footprint metaphor used by Dobson implies that individuals who recognise their footprints to be too large can satisfy their responsibility to those impacted by simply reducing the size of their footprints. But “unless ‘doing one’s share focuses most of all on bringing about structural change, the deactivation potential of the ecological footprint metaphor would be of concern” (ibid., p. 216). In addition, it should be added that reducing an individual’s footprint in a developed country does not necessarily enable access of an individual in a developing country to any resources. In this case, even when focusing on bringing about structural change, it would be extremely difficult to effect ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 7 The ecological citizen and climate change changes at the global and national economic and institutional scales which could allow such access by those currently disadvantaged. Second, changes in individual’s impacts may not be sufficiently large. This point is recognised by Valdivielso (2005) who suggests that many motivated ecological activists do not have the opportunity to maintain sustainable consumption (p. 244). Living in the developed world often means adhering to a minimum living standard that embodies a lifestyle intricately intertwined with patterns of consumption, which in turn are culturally and socially embedded needs of mobility, food, work, housing, training or leisure. As a result, in these cases “the least possible impact is often still much higher than the desired impact” (ibid., p. 244). The above discussion shows that ecological citizenship is a young and largely theoretical concept. Despite the criticisms outlined, the concept may have explanatory power in areas of human motivation and behaviour that extends beyond that of other approaches. 2 Case study: Two coastal communities in British Columbia The fieldwork for this research was undertaken from July 2004 to May 2005 in Victoria, British Columbia (BC) and on Salt Spring Island, BC, both located on the southern tip of Canada’s Pacific coast. Participants were recruited selectively on one hand, representing key actors on climate and other environmental or local issues, and purposely on the other hand, representing a spectrum of the population at large. The latter sample was recruited in parking lots of local malls and supermarkets, a mother and toddler group in both locations, a sailing club, and a golf club in both locations. In total, 86 participants partook in the research, 45 in Victoria and 41 on Salt Spring Island. Of these, in Victoria 27 were selected participants (including three experts on climate change), and 18 were purposive participants. On Salt Spring Island, 17 were selected participants and 24 were purposive participants2. The methods of data collection included, in this order, semi-structured interviews, a Q sort, and two focus group workshops, one in each case study location. The semi- structured interview questions were developed from an initial exploratory round of 2 In this paper, participants are referred to by their anonymous synonyms. For example, SSI13K is key actor participant number 13 from Salt Spring Island, while VIC8P is purposive participant number 8 from Victoria. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 8 The ecological citizen and climate change interviews with broad questions eliciting themes from participants about regulation, institutions, behaviour, and knowledge about climate change. The Q sort was developed from transcribed interviews as well as popular and scientific literature on climate change to represent the multitude of discourses or the “concourse” of the issue (Stephenson 1978; Brown 1999). The focus group workshops served as a deliberative forum that reflects the social dimensions of attitudes (Krueger 1997; Barbour and Kitzinger 1999; Oates 2000). During the workshops, participants were asked to reflect on key issues by drawing mind maps (Buzan and Buzan 1995; Buzan 2002) and to consider the results of the Q sort. Two sets of maps were produced, one drawn individually, and one drawn in a small group, after deliberation. The results of these three techniques were used for triangulation. For the sake of brevity, the analysis here focuses on the results of interviews and the focus groups. Other work considering perceptions of and responses to climate change by laypeople suggests that perceptions are context-specific (Lorenzoni et al. 2005). It is important to note that the results of this work emerge from and are to be considered in their specific local context on Canada’s west coast. 2.1 A civic responsibility “Every citizen has to be on board this train” (SSI9P, 28 May 2005). Civic responsibilities or duties are related to individuals’ actions through the remote connections between individuals’ lives and the temporally and spatially scaled consequences of their actions, or what Dobson (2003) calls the relationships giving rise to citizenship obligations (p. 129). This section argues that the responsibility described by participants of this research is of a civic nature for three reasons. First, the collective consequences of individuals’ private activities are recognised as important despite the fact that they occur outside of the individual’s immediate reality, and in spite of the incremental nature of individual contributions. Second, participants feel they owe a nonreciprocal, non-territorial responsibility to future generations and current generations living elsewhere (particularly in developing countries). Third, the responsibility is rooted in a sense of interconnectedness that describes the connections and relations between individual’s lives which give rise to citizenly obligations. The following paragraphs illustrate this with direct quotes. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 9 The ecological citizen and climate change The most dominant and uniform outcome of the case studies conducted for this research is participants’ sense of individual responsibility for both causing and ameliorating climate change. Throughout interviews, the individual is evident as the key actor bearing responsibility for causing and ameliorating climate change. The implied understanding in a large majority of answers to the question ‘who do you think is responsible for causing climate change?’ is ‘we all are’. Asking ‘who is it up to do something about climate change?’ prompted the majority of participants to reply ‘to everyone of us.’ Participants were asked specifically how those responsible for causing climate change and those who should do something about it compared. Most respondents do not see a difference between the two groups. This is important because it illustrates what one participant exemplarily put … if you are a member of western society, … you are responsible by participation (SSI3K). This statement underlines that this participant perceives the individual in western, developed societies as the key actor bearing responsibility, and therefore, simply by virtue of participation in the society, as the responsible agent. This is implied in every interview but one, that of the strongest climate change sceptic, who felt that if climate change were real, it would be up to governments to address the issue. Participants of this research consider themselves part of a global society. In this view, the individual constitutes a part in a greater collective that shapes and is shaped by this collective. This reflexive relationship is mirrored in participants’ sense of interconnectedness with other individuals across the globe, current and future generations, and the incremental influence their own living standard may have on those of others elsewhere. As indirect as this connection may be, it is one of the prime influences in this research on individuals’ perceptions of their role in a global collective. In this aggregate view, individuals’ contributions to the common good and the range of possibilities in a common future embody the incremental nature of the responsibility felt by participants: I don’t necessarily do it from a climate change perspective but more so from being a good citizen by not over-utilising water, or electricity, trying to minimise that and trying to be really economical in my vehicle and food choices (VIC12K). Thus, the individual obligation for action expressed in interviews is not just that, an individual responsibility. Rather, it relates to how people perceive themselves to be part ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 10 The ecological citizen and climate change of a local community, the nation state, and global society, in which sustainability is a key objective. The obligation felt therefore exceeds the boundaries of the immediate reality to extend to lives lived elsewhere and in the future, even non-human lives, and the integrity of the planet’s ecosystems as a whole. For these reasons, this responsibility concerns the civic realm of individuals’ lives. This closely resembles what Barry (1999a) calls the “collective enterprise of achieving sustainability” (in Dobson 2003). Further, in order to understand why the term ‘civic’ accurately describes the obligation felt, we need to examine the spatial and temporal dimensions of this obligation. Participants feel that the collective responsibility lies jointly with all those who contribute to the problem by living in the North. This notion of a collective yet individual responsibility is important in order to understand how participants perceive their lives to influence those of others elsewhere and in the future. Spatially, the responsibility is thought to reach across continents to lives of people only most indirectly connected to those of the interviewees. Yet, as argued above, this connection is important because by comparison, the effects of a life lived in the North are perceived to extend beyond national boundaries and across the world in a globalised reality, while those of a life lived in a developing country are seen as relatively inconsequential as far as causing climate change is concerned: Who is causing the climate to change right now? We all are. Everyone of us. Let me qualify that. All of us in the industrialised world are. Certainly not the third world nations. It is all of us in the industrialised world (SSI8P). Temporally, the dimensions of the obligation extend to an unknowable future and to future generations who will seek livelihoods and opportunities. They will also be impacted by and need to adapt to those consequences of climate change which current generations fail to avoid. Whether implicitly or explicitly, the majority of participants acknowledge a responsibility toward future generations: [Who do you think you’re benefiting in your actions to reduce your emissions?] Our children I think. Generations to come. It’s like planting walnut trees. They take 40 years to mature, why would you plant one? [So you feel you have a responsibility to future generations?] Ya (SSI6P). I don’t understand how anyone can have an ethic that says that we are responsible for the impacts of our behaviour on other people and that we have a responsibility not to harm them, and to limit that morality only to existing people. It makes no sense to me at ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 11 The ecological citizen and climate change all. And yet, that is the assumption that is built into all the economic analysis, … and many ethical theories (VIC19K, emphasis in the original). In interviews, participants draw a link to future generations by referring to children. Participants also consider the impacts of climate change on people in other, predominantly developing countries, removed from their own immediate reality, as a group to whom action to reduce emissions is owed. To further clarify this sentiment, participants were asked during the focus groups “To who do you feel you owe the responsibility for responding to climate change?” The mind maps drawn individually show there are essentially four conceptions about responsibility. First, participants mention “our children” and “future generations” (SSI4P, SSI12P, VIC5K, VIC6K, VIC13K). Second, some participants refer to “the Earth” or “all life on Earth” (SSI6K, SSI9P, SSI12P, SSI13P, VIC4K, VIC13K). Third, two participants wrote that they owed the responsibility to “the global community” (SSI12P, VIC18K). Finally, across interviews with almost all participants implicitly, the responsibility is also owed to the self – to protect integrity, build identity, and reduce cognitive dissonance: I owe it to myself to live with integrity, to be proud of the path I’ve chosen, to sleep soundly at night without guilt, knowing that I’ve done all I can to protect life on earth (VIC4K). One participant included references to all four of the above (SSI13P). 2.2 Characteristics of civic responsibility It has been suggested that although ecological citizenship is a politically based notion, its activities and principles are not solely confined to the political sphere as narrowly conceived (Barry 1999a). This research provides further evidence that ecological citizenship encompasses dimensions excluded from traditional political citizenship thinking, or the “sub-political realms” (Beck 1992, p.14), the private and specifically economic realms of individual lives (e.g. Beck 1997; Dryzek 2000). The following paragraphs demonstrate three specific characteristics of the civic responsibility, one that concerns individuals’ political agency as voters, one that relates to their economic agency as consumers, and one that concerns the power associated with a Northern lifestyle. This section thus shows that the characteristics of ecological citizenship as it is described here include but extend beyond the political realm (cf. Dobson 2003; Horton 2005). ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 12 The ecological citizen and climate change Participants link the responsibility to individuals’ roles as voters, which further supports the argument that it is a civic responsibility: I think it is even more important that individuals recognise their role because they are also voters. If you believe that government has a key role, who is it that tells government what to do? It’s the electorate. So, if individuals feel that it’s important, then theoretically governments will also feel that way. In this way individuals are pivotal (SSI7K). This quote highlights first, that the responsibility is tied to the democratic and political agency of individuals, and second, that it is contingent on other individuals’ responsibility – be it recognised by those or not. In this way, individuals’ roles are situated among a collective of responsibilities. While part of the responsibility is held by government, participants express specifically that should the government not recognise or honour its responsibility, individuals are still obliged to their own responsibility, and vice versa. Everybody has to play their part. You can’t just rely on government to legislate and you can’t just rely on people and communities to do things (SSI8K). Every member of society is expected to recognise his or her responsibility, and government is expected to recognise its responsibility. These incremental responsibilities are, however, not de facto but only theoretically contingent on each other: If governments fail to act on their responsibilities, this does not diminish the responsibility of citizens, and vice versa. Individual responsibilities are honoured by empowered individuals who are convinced that governments either cannot or will not live up to their part of responsibility. For this reason, the eventual responsibilities to future generations are handled in a similar way. This further illustrates the non-reciprocal relation between the responsibilities of current and those of future generations. Participants link the responsibility also to economic agency and it is here that the notion of ecological citizenship demonstrably extends beyond the political realm of an individual. As one participant put it: “It is the individual consumers who are ultimately responsible” (SSI6K). Much in the same fashion in which individuals’ consumption is linked to causes of climate change, participants bring consumer choices into focus when discussing responsibility for climate change. A number of responses indicate that participants believe in market regulation through consumers’ power: a significant change in demand will effect a change in supply. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 13 The ecological citizen and climate change Further, the sense of responsibility is also connected to Northern lifestyles that take access to fuel and water for granted. Participants are aware that their lifestyle hinges on such expected resources, and compare their own living standard to others in the world. [I]n the western world particularly we are responsible. It’s our lifestyle. We have gotten used to it and we perpetuate it with the ‘cheap gas, cheap water syndrome’ (SSI11K). Implicit in the phrase “the western world” is that this lifestyle, at the root of global problems such as climate change, involves more than the fair share of resource consumption per individual. Living in a developed country like Canada thus becomes a privilege which is tied to a responsibility. Someone likened it to […] the whole world coming to the banquet table […] and we’re lucky enough to be at the front of the line – how much do we take? […] We are really by mistake taking too much and we have to stop. I guess I have a sense of fairness, a sense of responsibility (SSI6P). Implicit in this metaphor is that future generations are not in the line yet and will be affected by the choices made before they were alive. In this fashion, the responsibility, once again, extends to future generations. A number of participants relate the privilege to live in a developed country to power, and through this, indirectly relate the responsibility to power: I think people who have more power have more responsibility. […] I think we are very privileged here compared to other parts of the world and with that privilege comes an obligation (VIC17K). From the above, there are clear indications that the multi-facetted nature of the sense of responsibility felt by individuals certainly includes the civic realm and thus is felt to constitute a civic duty. Therefore, to an ecological citizen, the private realm is included in acting as a citizen. Thus, political and economic agency together represent some of the specific dimensions of participants’ sense of responsibility: for causing the problem of climate change on one hand, and for helping to alleviate it on the other. What are the underlying themes that ground participants’ understanding of civic responsibility? The following section considers three particular issues that are at the heart of the felt individual responsibility: interconnectedness, identity and virtue, and individual leadership. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 14 The ecological citizen and climate change 3 3.1 Foundations of ecological citizenship in practice Interconnectedness In the early stages of the empirical research, it became evident that participants consider a sense of interconnectedness in at least some or, in a few cases, most of their daily and long-term decision making. As a result, the question “Do you feel that actions in your everyday life affect other people, perhaps in other locations?” was included in the semistructured interviews. The rather unanimous response to this question implicit in interviews of 73 participants is demonstrated by the following exemplary quote: Everything we do has an impact elsewhere, as small as it may be (SSI14K). The sense of interconnectedness described by participants fosters individuals feeling part of a global collective. The main premise participants identify is that their participation in society has consequences that may be removed from their own immediate reality, extending to places far away and into the future. Participants demonstrate that their knowledge of the causes of environmental problems, combined with their perception of increasing globalisation, yields a notion of interconnectedness that is crucial to understanding the ways in which these individuals think themselves to be part of collectives. As a direct consequence of Canadian media failing to link local climate impacts to climate change, and portraying climate change as an issue of greenhouse gas reduction not adaptation to impacts, participants see their contributions to the problem in the context of impacts that are depicted by the media in other, often developing countries. An individual’s sense of an indirect connection with others through interacting, global economic and environmental systems, and the far reaching consequences of individual behaviour, for example, from fossil fuel use, are a key part of how participants understand individual responsibility. The majority of participants feel their behaviour and decisions affect others, elsewhere and in the future. This demonstrates that the role of the global collective of humanity is key because it is the contingent backdrop against which individuals recognise their incremental responsibility. Again, this reflects precisely what Barry (1999a) calls the “collective enterprise of achieving sustainability” (p. 231) but in the context here it emerges from a specific analysis of perceptions and interpretations of climate change. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 15 The ecological citizen and climate change The interconnectedness to future generations occurs in two ways. First, as an extension of feeling connected to people alive now, as shown above. In this case, the interconnectedness arises when individuals realise that the connection they apply to current generations in developing countries also extends to future generations there. Second, individuals explicitly mention their responsibility to future generations specifically. They thus feel connected to people in the future by understanding the possible future implications and consequences of actions now. This is discussed in section 4. 3.2 Identity and virtue Evidence from interviews suggests that where individuals’ identity involves valuing virtuous behaviour, participants provide rationales for their actions that are specifically linked to their identity through the virtue embodied in the activity. Participants commonly responded positively to my question whether they felt they had benefited from acting in response to their knowledge about climate change. The importance of such behaviour can be detected in quotes that relate to one main theme. The most common notion implicit in participants’ explanations is a sense of improved self-image, a sense that their actions are congruent with their underlying beliefs. I don’t think we should be living our lives damaging the rest of the world by what we do. For me, and for my wife too, those things make us feel better, make us feel like we are doing something to help the world and mitigate the damage (SSI11K). A number of dimensions further define the role played by identity. In most participants’ cases, the underlying belief structures suggest it is ‘good’ to ‘leave the world a better place’. Others feel a sense of altruism in which the incremental contribution made to the greater good of others is important to participants’ self-image. Some participants also feel personally empowered by enacting the beliefs that support their identity. Yet another dimension relates to participants’ sense of their life’s meaning and worth. Underlying all of these aspects, however, is the value that is placed on an equitable global society, now and in the future. Individuals’ identities are the link between this aim and acting on the civic responsibility felt. 3.3 Leading by example Participants recognise their individual responsibility as only theoretically contingent on other individuals’ responsibility – whether the latter act on it or not. They feel obliged to ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 16 The ecological citizen and climate change act on their responsibility for climate change regardless of other people acting on theirs. Yet, they clearly demonstrate that they believe individuals’ contributions to be only increments of the whole, and hence, in order to achieve effective action on climate change, the collective is perceived to be obliged and required to act. For a number of participants, this understanding yields a sense of individual leadership which in turn supports the link to identity outlined above. Further, participants demonstrate that they hope their personal commitment acts as a positive example that others may follow. However, while participants would like to encourage others to act similarly, they are careful neither to lay blame nor to impose their own values onto others. Individuals’ perception of leadership emphasise the hope to inspire others to act on climate change: I believe in the ripple effect: If I do my little part, … then the people that are part of my life … each doing our own little thing, and hope that it will gradually become a big thing (SSI5P). This underscores that participants believe climate change to be a collective problem which can only be solved by collective efforts toward equitable solutions. The three foundations of being a good ecological citizen, interconnectedness, identity and virtue, and leading by example, are all linked to an underlying concern for equity, for the wellbeing of future generations and those currently affected by the impacts of climate change. The following section discusses the intra- and intergenerational aspects of equity as they are evident in the results of the case studies. 4 Intra- and intergenerational equity During the focus group workshops, participants were asked to respond to the question “What type of responsibility do I feel?” by drawing a mental map. The deliberations on the maps support the findings from interviews that equity considerations, among others, are part of the sense of individual responsibility described by participants. Figure 1 below shows a mental map drawn by a group of three participants in Victoria in May 2005. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 17 The ecological citizen and climate change Government belief in community of citizens A denial culture The grieving process Religious beliefs Recognise it as death Value of self or others prevention Responsibility By not doing something we “hurt” others (people die due to climate change) Prevention - our culture - choosing with our culture-forced paths Feeling helpless prevents action Caretakers of the Earth for future generations Humans All species Figure 1: What type of responsibility do I feel? Group mind map drawn during Victoria focus group (VIC5K, VIC13K, VIC18K, 29 May 2005). ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 18 The ecological citizen and climate change The themes on the map illustrate two dimensions of equity. First, the notion of “hurting others” as a result of lack of action on climate change supports the analysis on interconnectedness above, illustrating the causal link drawn between incremental contributions to emissions and effects on other people. Similarly, reflecting on people dying because of climate change in the context of these participants reveals that in Canada, very few if any casualties have resulted from climatic impacts. This comment therefore relates to people elsewhere. These two insights demonstrate that participants think about intragenerational equity, that is the relationship between those emitting and those bearing the burden of climate impacts. Second, the phrase “caretakers of the Earth for future generations” shows that current generations have a direct obligation not to preclude opportunities of future generations – the essence of sustainability. The root of this, however, is what participants elaborate in interviews; the responsibility is driven by the ambition to contribute to a more just and equitable world. In support of this, the model shows explicit concern for human and non-human life in the future. These insights indicate that intergenerational equity is considered explicitly by participants of this research, and underlines that they are motivated by this understanding to help alleviate climate change. A key characteristic of both intergenerational (and intragenerational) equity is that they are non-reciprocal. This unidirectional impact of an individual life on others now and in the future is a crucial component that characterises the civic duty embedded in the responsibility described above. It means that while participants understand their responsibility to be contingent on that of others, there are societal groups which are exempt because they do not participate in causing harm: future generations and developing countries. However, an exception to this is when cause for reciprocity of intragenerational equity is perceived. For example, while societies in developing countries historically have not contributed to climate change and are struggling to meet their population’s needs, recently growing economies, particularly China and India, are seen as recent contributors and therefore participation in emission reduction to a degree is expected. This is in light of these countries’ growing industries and living standards that may raise emissions in those countries for the foreseeable future. Every participant who raised intragenerational equity however, made clear that the North has no right to deny the growing economies their opportunities for development, similarly to this quote: ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 19 The ecological citizen and climate change I mentioned China and India. Having been there, I have mixed feelings about that, because in North America we can say “they shouldn’t be polluting so much” but why should they not want to have the same standard of living that we have? So to say “You can’t have industry, stay the way you are” is unfair (SSI3P). This illustrates the way in which the development paths of developing countries are considered, and how inter- and intragenerational equity are perceived to be related. Future generations are exempt from the reciprocity simply by not being alive yet, which prevents their actions from having retroactive impacts. By understanding the role of current generations as “caretakers of the Earth” (see figure 1), participants demonstrate that their responsibility is non-reciprocal, as a carer/cared-for relationship is one of power. Decisions now, as argued above, are understood to imply an obligation that comes with the power associated with a current Northern lifestyle. 5 Conclusion Taken together, the above provides indication that the obligations embedded in an individual’s responsibility match what Dobson (2003) calls “asymmetrically sized ecological footprints” (p. 127). Such obligations are meant to ensure that the collective impact of individuals does not foreclose opportunities of others, whether they are alive now or yet to be born. Consequently, as the responsibility felt by participants includes considerations of equity, it closely matches the civic duties associated with ecological citizenship as argued by Dobson (ibid.), Horton (2005), Sáiz (2005), and Carter and Huby (2005). Participants of this research perceive an individual responsibility for their incremental contributions to climate change. This responsibility bears the characteristics of a civic duty owed non-reciprocally to those currently affected by climate change impacts and to future generations. While the duty is thought to be contingent on a collective responsibility of the developed North, it is acted on independently thereof. It implies civic agents to be part of a greater, even global collective that is responsible for causing climate change and responding to it. The duty is conferred by virtue of participating in a Northern, developed society whose living standards have collective consequences for both human and non-human life elsewhere in the world and in the future. Intergenerational (and intragenerational) equity is thus a key element of this duty. Consequently, it is a civic obligation that extends beyond the political and public realms ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 20 The ecological citizen and climate change to encompass private activities with public implications. Considering this evidence, the responsibility described by participants exactly matches that giving rise to ecological citizenship as argued by Dobson (2003; 2005). The high consistency of views in this research suggests that the key aspects of a civic responsibility for addressing climate change rely on shared understandings. Two important such understandings are first, valuing equity, both intra- and intergenerational, and second, the specific definition of sustainability which is negotiated and has been popularised by local actors. This research demonstrates that the future can play an important role in shaping how present generations understand and enact their civic responsibilities. Considering the implications of one’s actions in a context of intergenerational equity is thus a key trait of the good ecological citizen. By acting as caretakers of the Earth, ecological citizens now are aiming to achieve their vision of sustainability, that is meeting current needs without compromising future generations’ abilities to meet their needs. The views of the ecological citizen therefore embody sustainability, and particularly its consideration of intergenerational equity. The explanatory power offered by ecological citizenship in this context demonstrates that participants of this research seek agency on issues important to them, here climate change, beyond what they are afforded by the state. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 21 The ecological citizen and climate change Bibliography Adger, W.N. (2001). "Scales of Governance and Environmental Justice for Adaptation and Mitigation of Climate Change." Journal of International Development 13(7): 921-931. Adger, W.N. and Paavola, J. (2002). Justice and Adaptation to Climate Change. Tyndall Working Paper 23. Norwich: Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research. Adger, W.N., et al., Eds. (2006). Fairness in Adaptation to Climate Change. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. Barbour, R.S. and Kitzinger, J., Eds. (1999). Developing focus group research :politics, theory and practice. London: Sage. Barry, J. (1999a). Rethinking Green Politics. London: Sage. Barry, J. (1999b). Sustainability and intergenerational justice. In A. Dobson Fairness and Futurity: Essays on Environmental Sustainability and Social Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Barry, J. (2002). Vulnerability and Virtue: Democracy, Dependency and Ecological Stewardship. In B. Minteer and B.T. Pepperman Democracy and the Claims of Nature. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. Beck, U. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage. Beck, U. (1997). The Reinvention of Politics: Rethinking Modernity in the Global Social Order. Cambridge: Polity. Bell, D.R. (2005). "Liberal Environmental Citizenship." Environmental Politics 14(2): 179-194. Brown, S. (1999). Subjective Behaviour Analysis. 25th Anniversary Annual Convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis - “The Objective Analysis of Subjective Behavior: William Stephenson’s Q Methodology”: Chicago. Buzan, T. (2002). How to mind map. London: Thorsons. Buzan, T. and Buzan, B. (1995). The mind map book. London: BBC. Carter, N. and Huby, M. (2005). "Ecolgical Citizenship and Ethical Investment." Environmental Politics 14(2): 255-272. Christoff, P. (1996). Ecological Citizens and Ecologically Guided Democracy. In B. Doherty and M. de Geus Democracy and Green Political Thought: Sustainability, Rights and Citizenship. London: Routledge. Clarke, P.B. (1999). Deep Citizenship. London: Pluto Press. Dean, H. (2001). "Green Citizenship." Social Policy and Administration 35(5): 490-505. Dobson, A. (2003). Citizenship and the Environment. London: Routledge. Dobson, A. (2005). Citizenship and Sustainability - Paper submitted to the Conference "The Governance of Sustainability": University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK. Drevensek, M. (2005). "Negotiation as the Driving Force of Environmental Citizenship." Environmental Politics 14(2): 226-238. Dryzek, J.S. (2000). Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Goodall, S., Ed. (1994). Developing Environmental Education in the Curriculum. London: David Fulton Publishers. Hailwood, S. (2005). "Environmental Citizenship as Reasonable Citizenship." Environmental Politics 14(2): 195-210. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 22 The ecological citizen and climate change Horton, D. (2005). Demonstrating Environmental Citizenship? In A. Dobson and D.R. Bell Environmental Citizenship. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. Krueger, R.A. (1997). Analyzing & reporting focus group results. London: Sage. Lichtenberg, J. (1981). National Boundaries and Moral Boundaries: A Cosmopolitan View. In P. Brown and H. Shue Boundaries: National Autonomy and its Limits. New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield. Lorenzoni, I., et al. (2005). "Dangerous Climate Change: The Role for Risk Research." Risk Analysis 25(6): 1387-1397. Luque, E. (2005). "Researching Environmental Citizenship and its Publics." Environmental Politics 14(2): 211-225. Oates, C.J. (2000). The use of focus groups in social science research. In D. Burton Research Training for Social Scientists - A Handbook for Postgraduate Researchers. London: Sage. Sáiz, A.V. (2005). "Globalisation, Cosmopolitanism and Ecological Citizenship." Environmental Politics 14(2): 163-178. Seyfang, G. (2005). "Shopping for Sustainability: Can Sustainable Consumption Promote Ecological Citizenship?" Environmental Politics 14(2): 290-306. Smit, B. and Pilifosova, O. (2001). Adaptation to climate change in the context of sustainable development and equity. In J.J. McCarthy, O.F. Canzianni, N.A. Leary, D.J. Dokken and K.S. White Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability - Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Smith, G. (2005). "Green Citizenship and the Social Economy." Environmental Politics 14(2): 273-289. Smith, M.J. (1998). Ecologism - Towards Ecological Citizenship. Buckingham: Open University Press. Stephenson, W. (1978). "Concourse theory of communication." Communication 3: 21-40. Thomas, D.S.G. and Twyman, C. (2005). "Equity and justice in climate change adaptation amongst natural-resource-dependent societies." Global Environmental Change 15: 115124. Valdivielso, J. (2005). "Social Citizenship and the Environment." Environmental Politics 14(2): 239-254. Watson, R.T., Ed. (2001). Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report - Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2001. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. WCED (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Wisner, B., et al. (2004). At Risk. London: Routledge. ECPR Joint Sessions 2007, Helsinki 23