* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Is it Warm in Here? The Intractable Challenges of Climate

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

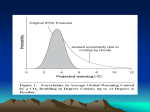

Global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Climate change, industry and society wikipedia , lookup

Climate change feedback wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Economics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference wikipedia , lookup

Carbon pricing in Australia wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

German Climate Action Plan 2050 wikipedia , lookup

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change wikipedia , lookup

Views on the Kyoto Protocol wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in New Zealand wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Economics of climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Carbon governance in England wikipedia , lookup

Decarbonisation measures in proposed UK electricity market reform wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Carbon emission trading wikipedia , lookup

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report wikipedia , lookup

Low-carbon economy wikipedia , lookup

Politics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme wikipedia , lookup

Mitigation of global warming in Australia wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence University Lux Convocations 5-14-2015 Is it Warm in Here? The Intractable Challenges of Climate Change David Gerard Lawrence University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lux.lawrence.edu/convocations Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Health Economics Commons, and the Political Economy Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Gerard, David, "Is it Warm in Here? The Intractable Challenges of Climate Change" (2015). Convocations. Paper 1. http://lux.lawrence.edu/convocations/1 This Convocation is brought to you for free and open access by Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Convocations by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is it Warm in Here? The Intractable Challenges of Climate Change David Gerard Associate Professor & Chair Department of Economics Lawrence University May 14, 2015 Thank you President Burstein for that introduction and for selecting me for this award. I have to admit that I really wasn’t prepared for the lead up surrounding this, so thanks to Mark and Geoff Gajewski and Linda Peeters for bearing with me. My colleagues have been so gracious and supportive in the past few weeks – I’m a little startled, but not surprised. We have a great faculty and it feels special to be the representative today. Congratulations to the students here. Wow, we have great students. I must say that after being at dinner last night I can’t help being a little envious that this award didn’t come with a Cup or a Blanket.1 Or maybe a Mace? The Faculty Marshall, Alan Parks, tells me that that is a “defensive” mace. If I might, I would also like to thank my wife, Kirsten, for being a great partner. Honestly, it just wouldn’t be possible to do what I do without her. (Slide 2) Even though it’s Convo hour, I want to start us off with a short quiz.2 For each of these two statements, tell me if the answer is true or false. If you have a pen you can write the answers on your hand to show me later. If you have room, maybe sign the Honor Code below it. First, Climate change is an urgent problem. Second, it will be extremely difficult to reduce use of fossil fuels. The point of this quiz is that most people do not answer both questions the same way. Some believe that climate change is an urgent problem that we can easily address by reducing fossil fuel use. 1 My thanks to LeRoy Frahm for delivering a commemorative cup to me in the week following this Convocation. The quiz is described and discussed in Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman. Climate shock: the economic consequences of a hotter planet. 2 1 Others think that weaning ourselves from fossil fuel use would be prohibitively difficult, but also believe that climate change just isn’t *that* urgent of a problem. I am going to show you that both of these statements are, in fact, true. Along the way, I will give you some sense about how economists think about economic growth and the environment. (Slide 3) Let’s start with economic growth. It seems clear that higher income levels tend to be associated with some desirable outcomes. The slide shows figures from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. High income countries have higher incomes (of course), longer life expectancies, and lower infant mortality rates. The bottom billion live on a dollar or two a day and see almost one in ten of their children die by the age of five. These are the most-recent figures available, but it is worth noting the extraordinary improvements over the past fifty years. (Slide 4) Here are the same metrics just for the world’s middle class – which accounts for about 70% of the population. In 1960, life expectancy was only 47 years – I’ll come back to that number later – but now it’s up to 70. Under-five mortality rates have dropped dramatically -from 2 in 10 to only 1 in 20. And, of course, income has increased. (Slide 5) But what about environmental quality? Well, economists have thought a lot about that and we’ve come up what we call an “environmental Kuznets curve” – the inverted U that you see in this picture. The X axis here measures income per capita and the Y axis some measure of pollution (in this case Sulphur dioxide). As countries develop, economic growth results in greater pollution, reflecting (more or less proportional) increases in energy and production inputs. As income continues to increase – people are less willing to put up with environmental degradation as a cost of economic growth (though one of the current puzzles is why people put up with it for so long) --- and technology adoption and regulations begin to delink this relationship. Pollution goes up, pollution goes down. 2 This figure shows a fitted data for 41 countries over time. Note that pollution peaks at about $10,000 per capita income for this pollutant.3 (Slide 6) This figure is a mainstay on the EPA website tracking different US economic and environmental variables since 1980.4 The economy has more than doubled in size and in per-capita terms income is up 77%, the U.S. population has increased 40%, and vehicle miles travelled have doubled. Yet, energy consumption is only up 25% and, despite a much larger economy, we’ve cut emissions of the six so-called “criteria” pollutants by 62%. So the economy has more than doubled and pollution has been cut in half – On that basis, I will tentatively conclude that economic growth and the environment can be friends. (Slides 7 & 8) If you didn’t follow the squiggly lines on the last couple slides, the map of US sulfate deposition gives the same story.5 Here, green is good, brown is bad. Sulfates come predominantly from fossil fuel combustion, so the dark brown patches across the rust belt essentially track emission from coal power plants making their way from west to east. The first picture shows 1988 data. Twenty years later, the picture looks much different. Better technology, cleaner fuels, and the helpful hand of the 1990 Clean Air Act’s “cap and trade” program, have made substantial inroads. Here is the key point: when we reduce emissions we almost immediately reduce the impacts. Lower SO2 emissions today means less acid rain tomorrow. We get essentially the same type of story for the six criteria pollutants – NOX. SOX, lead, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter – resulting from sharp reductions in industrial emissions. Here’s another map, this one of ammonium deposition. Ammonia emissions are largely the result of animal waste rather than fossil fuel combustion, so when we roll back the curtain here the picture is not as pleasant. This is something you might consider the next time you look up to let a cool summer rain wash over your face. The salient point here is that if we reduce ammonia emissions today, these effects will change tomorrow. 3 The curve is fit using information from Jeffrey A. Frankel & Andrew K. Rose, 2005. "Is Trade Good or Bad for the Environment? Sorting Out the Causality," The Review of Economics and Statistics 87(1):85-91. 4 The URL as of May 2015 can be found at http://www.epa.gov/airtrends/aqtrends.html#comparison 5 The graphics are from the National Atmospheric Deposition Program http://nadp.sws.uiuc.edu/data/animaps.aspx 3 (Slide 9) Carbon dioxide is different. Unlike other pollutants CO2 stays in the atmosphere for a long time – from 40 to 110 years. So, when I drive my car today, the CO2 I burn will still be trapping heat long after I’m dead. That’s where the bathtub analogy comes in. The faucet represents current emissions – that’s stuff we’re burning year to year. The level of the tub represents what’s up in the atmosphere – atmospheric CO2 concentrations. This tub has the drain open with natural “carbon sinks.” But if the water is coming in faster than the tub is draining, the tub fills up – you might try this at home. Wagner and Weitzman say this an overused analogy, but they also say that up to 75% of MIT students fail to grasp this distinction between emissions and the concentrations on the first try – emissions are what we call a flow variable and concentrations are a stock. Although it’s the flow variable that fills the tub, it’s the stock in the atmosphere that is what traps heat and affects climate change. Reducing the atmospheric concentrations we need to turn off the faucet or unplug the drain. (Slide 10) Here’s the faucet. These are CO2 emissions for the past 50 years in the US and worldwide.6 You can see that in 1965 the US accounted for quite a large share. World emissions have tripled over this period, and are increasing at an increasing rate. (Slide 11) Not surprisingly, the tub has been filling up. These are CO2 concentrations for the past 50 years, increasing at about 1.5 ppm per year.7 In the past few years, however, the increase has been more like 2 ppm per year. To give you an idea of what this means, preindustrial levels were below 300 and sort of a best-case scenario to stabilize is around 450. (Slide 12) These are the projected temperature changes given different CO2 concentrations.8 I will focus here on the 550 ppm, which is where we would be in 2090 a 2 ppm per year. The red line shows a range of estimated outcomes – the point estimate is about 5-6 degrees Fahrenheit, with 2 on the low end and 8 on the high end. As the concentrations increase, both the lower-end estimate increases and the range widens! Based on these numbers I conclude that earth is, indeed, going to warm up. (Slide 13) The news isn’t any better on this slide. 6 British Petroleum Statistical Review of World Energy, 2014. The data in the image are from National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/graph.html 8 The slide is from Nicholas Stern, The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge University Press, 2007. 7 4 This slide shows us the so-called “tails” – the probabilities of warming greater than 11 degrees F. These “monsters in the closet” type scenarios, which would likely broach any number of ecological tipping points and result in catastrophic climatic outcomes. The message is that probabilities increase exponentially as CO2 concentrations increase.9 (Slide 14) I would like to offer an analogy to help you remember the issue here, what I will call the “underused” bathtub analogy. That is, you don’t want to throw out the baby with the bathwater, but you still need to do something about all that bathwater. (Slide 15) Here’s a thought -- how about turn off the faucet? The idea here is what would the emissions trajectory have to look like to stabilize atmospheric CO2 emissions?10 The middle line shows about a 50% cut in CO2 from current levels, leading to our 550 ppm scenario. The lower line is more ambitious and is what has generally been targeted, because it is consistent with projected warming of 2C (3.6F). Earlier this week, Provost Burrows circulated an email advertising today’s Convocation that included the question of what does it mean for something to be “intractable”? I have a three-word answer to that question: (Slide 16: NOT GONNA HAPPEN) Or maybe that’s four words? However many words that is, I argue that there are at least four main reasons why we won’t see major traction on this issue. First, there is a tight link between energy and economic development. Second, despite big increases in renewable energy resources, fossil energy use is still rapidly increasing. Third, even in wealthy countries, we don’t see support for radical emissions cuts. The fourth point speaks for itself -- wildly optimistic emissions-reductions scenarios are wildly optimistic. Let’s go thru these in turn: 9 The data are from Wagner and Weitzman, Climate Shock. The slide is from Nicholas Stern, The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge University Press, 2007. 10 5 (Slide 17) This slide simply maps levels of per capita GDP and per capita energy consumption, and is turned into a GIF that shows the relationship for 1971 – 2010. Higher levels of economic activity require more energy.11 (Slides 18 and 19) I know what you’re thinking – sure people are using more energy, but can’t his energy come from renewable sources! So let’s take a look at electricity generation around the globe by fuel source.12 This is a slide from a few years back when I worked on a few teams thinking about reducing greenhouse gas emissions. These four regions account for about 90% of electricity generation, and you can see that the blue portion – fossil fuel – dominates. As I was preparing this presentation, I wondered how up-to-date this slide was, and it turns out things have changed. Take a close look at Asia and notice two things: First, it accounts for about one third of world here. And, second, there is just a little tiny sliver of Green energy. You might also note the green areas in the US and Europe. (Slide 19) Now here we see Asia has ballooned – its generation grew almost 60% over that 7year period. Although there is a lot more green (renewable energy) – particularly in Europe – it is still a blue (fossil-fuel based) planet. World generation went up 25% overall and the portion from fossil fuels stayed almost exactly the same. Annual growth rate in energy is 5% per year – at these rates world electricity generation will double again by 2030. The message here: The size of those pies is going to double in your lifetime. To get our 50% reductions, we need to cut the amount of blue by half or more while expanding the pies by a factor of two or more. This led me to conclude a couple of things. First, (Slide 20) Asia is a pretty busy place. This figure shows the growth in big cities by continent, and Asia accounts for approximately the same number of big cities as Europe, the Americas, and Africa combined.13 Even though I knew that, I still look at this figure and said “wow” A second conclusion is that we sure seem to have a lot of fossil fuels. If you’ve been paying attention, you know that supply increases have radically reduced US natural gas prices and world oil prices over the past few years. Domestic natural gas production is up 50% in the past ten years and domestic oil production has almost doubled. 11 The Gif is taken from the Stochastic Trend website, “Energy and Economic Growth: The Animated Gif,” http://stochastictrend.blogspot.com.au/2014/06/energy-and-economic-growth-animated-gif.html 12 The electricity data are from the Energy Information Agency (EIA), at http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/international/electricitygeneration.html 13 Figure from Charles I. Jones, “The Facts of Economic Growth,” NBER Working Paper 21142, May 2015 6 This (Slide 21) night time view of North America tells the story.14 You will see all the big cities lighted up on the map here – Los Angeles, Chicago, Menasha, and … what’s this city here? No, actually, it’s from flaring off natural gas in the oil fields in North Dakota. Natural gas is a byproduct of oil production on the frontier, but the price of natural gas is so low that it’s more profitable to burn it than sell it. (Slide 22) Next up, I have some good news and some bad news. The good news is that 38% of US citizens think global warming is a top priority. (Slide 22 Animation) The bad news is that that ranks below pretty much every major public policy issue – terrorism, the economy, jobs, health care, crime, race relations, moral breakdown (moral breakdown?). The environment generally fares better on this list, but environmental policy is certainly one of the most polarized policy areas.15 (Slide 23) Polarized isn’t necessarily paralyzed. EPA does has the authority to regulate CO2 emissions and plans to finalize a rule this July. Let me read you about this rule:16 [The EPA rule] would fundamentally restructure the nation’s electricity sector, increasing the use of renewables like wind and solar, lowering electricity demand through energy efficiency and demand-side efforts, and using significantly more natural gas and less coal to generate electricity [my emphasis]. Now, here’s the punch line: If finalized, the rule would reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 30 percent by 2030. Let me say that again, a fundamental restructuring of the electricity sector buys us about 30% reduction in US emissions. So this is Convocation is kind of one big bummer so far. But help is on the way … (Slide 24: Fight Climate Change using this One Weird Trick) Of course, if you know anything about that one weird trick thing, you know that they don’t just *tell you* what the trick is. First, you need some background.17 14 The picture is from The New Republic website, “You Can See the Shale Boom from Space,” www.newrepublic.com/article/115806/shale-boom-visible-space 15 Pew Research Center, “Public’s Policy Priorities Reflect Changing Conditions at Home and Abroad,” January 15, 2015 http://www.people-press.org/2015/01/15/publics-policy-priorities-reflect-changingconditions-at-home-and-abroad/ 16 The quotation is from Brian Potts and Abigail Barnes, “Is The EPA's Clean Power Plan Legal?: Lawyers and Law Professors Disagree.” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2613763 17 William Nordhaus, The Climate Casino: Risk, Uncertainty, and Economics for a Warming World, 2013 provides a brilliant, accessible introduction and delineation of the economics of climate change. 7 Markets To paraphrase Homer Simpson,18 Markets are both the problem and the solution to all of our problems. Markets have been instrumental in fostering the extraordinary wealth in the western world. Wagner & Weitzman correctly in my view point out that markets with all their innovative and entrepreneurial powers are our only hope of steering clear of a climate catastrophe. Market Failure. Unfortunately, markets sometimes “fail” to generate an “economically efficient” result, particularly when all of the costs associated with production and use aren’t included in market prices. Markets don’t treat CO2 emissions as a cost When I get in my car to drive somewhere, the CO2 emissions that I generate will harm someone down the road. But, because I don’t pay the cost when I buy gas, I don’t consider that in my decision. The solution? Put a price on CO2. That’s right, a carbon tax. (Slide 26) There isn’t much dispute within the economics profession on whether this is the route to go. The University of Chicago’s Initiative on Global Markets19 surveys top economists from around the world on a variety of questions and here is what they had to say to the statement that carbon taxes are superior to other regulatory options. 60% strongly agree, 35% agree, 4% are uncertain, and only 2% disagree. These are weighted by each expert’s confidence in the statement (though I’m not sure how confident we should be given that those percentages sum to 101% (?!?)). I can think of a lot of reasons why the carbon tax makes sense, but I’ll just give you two: • First, tax something and you get less of it. • Second, a tax on carbon-based fuels makes clean alternatives like renewables and battery storage more attractive Economists at Resources for the Future estimate that a carbon tax could get rid of CO2 at about $12 per ton, compared to $40 for a gas tax, $50 for superior building codes, $85/ton for fuel efficiency standards, and $255 for weatherization tax credits.20 18 Homer’s quotation, of course, is "To alcohol! The cause of... and solution to... all of life's problems" in Homer vs. the Eighteenth Amendment. The episode aired in March 16, 1997, the day after I deposited my Ph.D. dissertation. 19 See IGM Forum at http://www.igmchicago.org/ 20 Alan Krupnick et al. Toward a New National Energy Policy: Assessing the Options, Resources for the Future, 2010. 8 An initial $25 per ton of CO2 tax would raise gas prices about a quarter a gallon and retail electricity prices about 10%. It would also raise about $125 billion per year, which is about 510% of what the federal government currently raises in income taxes. It’s probably worth noting what the one dissenting opinion, Ed Lazear from Stanford, had to say. “The magnitude of the problem is so great that no sufficient carbon tax is feasible worldwide.” So he doesn’t disagree with the statement as much as he thinks it’s not going to matter. To my mind, this tax is a good idea independently of whether it makes significant cuts to global CO2 emissions, and this is a near consensus view of the profession. (Slide 27) When asked whether we prefer carbon tax or income taxes, the profession pretty much unanimously chose the carbon tax. Why? Income taxes are a fundamental source of federal revenue, but when we tax something we get less of it – the income tax discourages some people from working. In contrast, CO2 emissions are highly correlated with emissions of all sorts of pollution – soot from coal, for example. Cutting CO2 emissions not only fights global climate change, it can have immediate public health benefits. The World Bank (Slide 28) includes carbon taxes as a pillar in its three-part plan to decarbonize the world economy, in this case by “getting the prices and policies right.”21 (Slide 29) Speaking of getting polices right, I’d like to return now to economic development and resilience in developing countries. Recall that middle income countries average about $3000 in per-capita income. The Figure here shows increases in per-capita income at various growth rates. At 5% middle income countries will enjoy our current standards of living (of about $30,000) by about 2060. At 3% it would be closer to 2100. At 1% never. My view is that development is essential not only in improving human welfare metrics we’ve seen, but also essential for making these countries more resilient in the face of climate change. So which one of these trajectories is most likely? 21 See World Bank “3 Steps to Decarbonizing Development for a Zero-Carbon Future,” May 11, 2015 http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/05/11/decarbonizing-development-zero-carbon-future 9 In the past 200 years the world has generated phenomenal (but extremely selective) economic growth.22 The principal factors underlying growth are: • • differences in physical capital (poor countries don’t save enough) differences in human capital (poor countries don’t invest enough in education and skills, particularly education of women) • differences in technology (poor countries don’t invest enough in R&D or technology adoption). Of course, these are proximate causes and the real question is not whether poor countries do these things, it’s why don’t they? (Slide 30) There are at several competing explanations, including Institutions, Culture, Geography, and Luck.23 As a “New Institutional” economist, I favor the institutions explanation, though this remains an open question. Institutions are “the rules of the game” -- both formal and informal constraints that define the incentive structure of societies. Acemoglu and Robinson argue that institutions encourage development when they provide appropriate incentives to invest and also constrain political power, thus limiting corruption. (Slide 31) On that note, I’m going to finish with a story that our majors learned about in the Senior Experience this past year – the remarkable turnaround in urban environmental quality. Urban life expectancy in 1900 was approximately 50 years old for white Americans, and only 30-35 years for African Americans. Life expectancies in urban areas were less than in rural areas. The plus symbols in the diagram are for urban whites – about the same as for Middle Income Countries in 1960! How bad was urban life in the early 1900s? Here is a taste:24 [Urban America was] a dirty place. Water and milk were contaminated with bacteria causing typhoid fever, dysentery, and diarrhea. (A sample of records of 35,000 Union Army soldiers suggests approximately 1/3 of adult Americans suffered from chronic diarrhea in 1900). Cities often failed to remove sewage and their streets were filled 22 Adapted from Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, Why Nations Fail: the Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. New York: Crown Business, 2012 and Daron Acemoglu, Institutions Political Economy and Growth. September 4, 2012. http://www-2.iies.su.se/Nobel2012/Presentations/Acemoglu.pdf 23 The two books featured are Douglass C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press 1990 and Acemoglu and Robinson, Why Nations Fail. 24 The figure is adapted from Werner Troesken, Race, Water, and Disease, MIT Press, 2014. The quotation is an amalgam of Troesken and Dora Costa and Matthew Kahn. "Public Health and Mortality: What Can We Learn from the Past?" Public policy and the income distribution. 10 with garbage and carrion… Infant mortality was 50% higher in the city than in rural areas. [Even those who survived were permanently scarred, shortening their lives at older ages…] Between 1902 and 1929, the urban waterborne death rate had fallen by 88%. (Indeed) by 1940, the urban mortality penalty had disappeared. What happened? Cities invested massive amounts of money in waterworks and water treatment. Indeed, some of the largest infrastructure projects in the history of mankind were city water projects. (Slide 32) Where did the Chicago Sanitary District get a billion dollars to finance its infrastructure spending? Werner Troesken (also a New Institutional economist, I might add) argues that the type of institutions that foster economic growth, also allowed municipalities to finance these water projects. In this case, people don’t loan money to the government if they don’t think they are going to get it back – credible political commitments facilitated massive borrowing and the result was an extraordinary improvement in living conditions and human well being.25 (Slide 33) The upshot of all of this is that “good institutions” have some desirable features. They promote economic development, facilitate enforceable public policies, such as a carbon tax, and they provide public bodies the ability to raise capital to finance large infrastructure investments. (Slide 34) So to finish, I have some take home points that I hope are transparent by this point. First, it is clear that we are not going to stop climate change in its tracks, but we can take steps to contain it. The economics literature directs us to the next two points. Economists overwhelming support a carbon tax to mitigate carbon emissions. Many of us support this position even if the policies apply only in the developed world. By curbing emissions provide some insurance against catastrophe. Economists also generally support economic development, which require growth-enhancing economic and political institutions (at least, according to the New Institutional school). The evidence supports the contention that development will improve resiliency of vulnerable populations in the face of climate change. Finally, not all hope is lost -- history provides some examples of extra-ordinary collective action in the face of extra-ordinary environmental problems. Thank you very much. 25 Werner Troesken, The Pox of Liberty: How the Constitution Left Americans Rich, Free, and Prone to Infection, University of Chicago Press, 2015. 11