* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Body`s Building Blocks

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides wikipedia , lookup

Paracrine signalling wikipedia , lookup

Gene expression wikipedia , lookup

G protein–coupled receptor wikipedia , lookup

Expression vector wikipedia , lookup

Ancestral sequence reconstruction wikipedia , lookup

Magnesium transporter wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

Metalloprotein wikipedia , lookup

Biosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

Genetic code wikipedia , lookup

Amino acid synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation wikipedia , lookup

Interactome wikipedia , lookup

Biochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Western blot wikipedia , lookup

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of proteins wikipedia , lookup

Protein purification wikipedia , lookup

Protein–protein interaction wikipedia , lookup

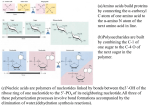

The Body's Building Blocks by: Heather Smith Thomas November 01 2002, Article # 3956 Like a structure made of tinker toys, protein is composed of smaller pieces--the amino acids. These can be rearranged to form the different types of protein-based tissues in the body. Protein is one of the basic nutrient elements of the equine diet, along with fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals, and it is necessary to the life and well-being of the horse. Crucial for tissue growth and repair, protein builds bones, blood, skin, hair, and muscle. What is Protein? Sarah Ralston, VMD, PhD, Dipl. ACVN, associate professor in the Department of Animal Science at Cook College, Rutgers University, says, "Proteins are chains of amino acids in various combinations. There are 22 from which to choose. They have a linear structure (the sequence of amino acids) and secondary and tertiary structure, where amino acids fold back on themselves and have linkages, looking like they are tied in knots. The structure gives a protein its properties." Muscle proteins are different from enzyme or hormone proteins, and they differ greatly from the wide variety of proteins in blood, for instance. "Proteins are continually being turned over in the body," says Ralston. "There is a constant sequence of breaking down and resynthesizing, according to need." The horse can synthesize most of the amino acids he needs, but some essential ones, like lysine, must be obtained from feed. If even one essential amino acid for a protein is missing from the diet, synthesis of that particular protein cannot continue. If the missing amino acid is necessary to a certain phase of body growth, its absence will prevent normal growth even if the diet contains enough of all the other ingredients. Young horses on diets low in lysine grow more slowly than those fed adequate lysine, according to the National Research Council's Nutrient Requirements of Horses. Ray Geor, BVSc, PhD, Dipl. ACVIM, is part of R and J Veterinary Consultants based in Canada, specializing in equine internal medicine, and he is a consultant for Purina Mills, Inc., in St. Louis, Mo. He says there is a lot we still don't know about protein nutrition in the horse. "In humans, we know that 11 of the amino acids are essential; we can only obtain them through diet," explains Geor. "Many of these are probably also essential in the horse, but currently we only have information on the needs for lysine and threonine. We need more research on requirements for some of the other amino acids, especially in athletic horses." Protein Quantity and Quality Legumes generally have more protein than grasses, which have a variable amount that's usually less than legumes. In a concentrate feed, manufacturers often add protein supplements, says Shea Porr, PhD, assistant professor of agricultural technologies at The Ohio State University. "Alfalfa can be anywhere from 14-16% crude protein to over 20%, which is very high for a forage. Grasses may be 10-14%, and I've seen grass hays as low as 6%. Protein supplements often run 40-45% crude protein. The most commonly used protein supplement in horse diets is soybean meal (which is usually 44% protein), usually in the form of a pellet." She says it is easy to tell the difference: In a sweet feed mix, brown pellets are soy supplement; green pellets are alfalfa meal. Protein quality, as opposed to quantity, depends on its balance of amino acids. If it has the right balance of all essential amino acids, it's a high-quality protein. If it's missing one or is low in one, it is considered poor-quality protein, explains Ralston. "Alfalfa and soybean meal have high-quality proteins in high concentrations for horses," she says. "Corn has low-quality protein because lysine and tryptophan (another amino acid) concentration is low." Corn is a good feed ingredient for adult horses, but needs supplementation for young horses. Green pasture with a mix of clover and grasses gives a nearly perfect balance of proteins, says Ralston. "Milk protein is the highest-quality protein," Ralston says. "Mares provide all the protein their babies need in terms of amino acids. Legumes have the next-highest quality, and they contain more total protein, in general, than grasses. Grasses are lower in tryptophan than legumes like alfalfa or clover, but are not deficient. Horses on green grass pasture have higher levels of tryptophan in their blood than do horses fed dry hay and lots of grain, probably because most grain mixes are predominantly corn. "The young, growing plant has the same amino acid content as a mature plant (once the amino acids are there, they remain there), but the mature plant has more fiber," she says. The proportion of protein in a given volume of plant material goes down as the plant ages. Therefore hay (cut when the plant is mature) has less protein per volume of dry matter than the young, immature grass or alfalfa plant. Protein quality and quantity can diminish in hay stored for a long time. "Proteins can be destroyed by oxidation," explains Ralston. "They are not as fragile as vitamins, but the secondary and tertiary structures of proteins can be affected by heat or oxidation, breaking the linkages between the amino acids (untying the knots). Some of the heat-induced changes make proteins more resistant to digestion, and the amino acids less available." How a Horse Obtains Protein When the horse eats feeds containing protein, structural linkages and strings of amino acids are broken up by enzymes in the digestive tract. Proteins are such large molecules that they cannot pass through the gut wall whole. They are broken down into individual amino acids and dipeptides (two amino acids hooked together), which are then absorbed through the wall of the small intestine. After passing into the bloodstream, the small components travel to body sites where they are needed, and are reassembled into specific proteins. Any protein not broken down in the small intestine goes on through the digestive system to the hindgut, where bacteria break it down and use it to make their own proteins, rather than proteins for the horse. How the Body Uses Protein Body cells pick up specific amino acids as needed. However, if there's a predominance of one amino acid over others in its class, it will reduce absorption of the others, says Ralston. That's where horse owners can get into trouble feeding extra protein as single amino acids like tryptophan or lysine. "If you feed large amounts of these, they out-compete other amino acids that may then be in short supply (in the horse's tissues)," she says. Porr explains, "The body breaks a protein down and absorbs its amino acids, and different tissues use the ones they need in order to produce whatever they are making. If a tissue runs out of a certain amino acid, that synthesis stops. It can't substitute another one. The process must wait until it gets the one it needs, or it may break the whole thing back down and put all the pieces back into the system because it can't finish its job," she says. How Much Does a Horse Need? Protein requirements vary, depending on whether the body is growing or maintaining its tissues. Foals, weanlings, and yearlings require more total protein and more high-quality protein (containing lysine) than adults. They are making more of the proteins needed to synthesize more muscle, bone, and cartilage as they grow, and they need more lysine than an adult horse which already has these tissues in place. What would be a poor-quality protein for a weanling would be very acceptable for an adult, says Ralston. The exception would be a lactating mare, which needs higher levels and higher-quality proteins (those with plenty of lysine) to produce milk. If she isn't getting enough, her milk production will drop. A lactating mare needs 1416% of her diet as protein, according to Porr. The young horse's greatest need for developing body tissues is quite early in life--in the last trimester of gestation and the first months after birth when he's growing fastest. Young foals need 16-18% of their total diet as protein, but they get that in milk, says Porr. Older foals need 14-15% protein in the total ration, assuming the protein is of good quality. By the time he is weaned, the foal's protein needs are much less than they were at one month of age. Foals weaned at less than four months of age should be given some sort of milk protein in addition to feeds designed for normal weanlings. "The spike in the growth curve occurs the first month or two of age, and slows progressively after that," says Porr. "With every phase--foal, weanling, yearling--you drop an average of 2% in dietary requirements. By the time a horse is three, he needs only about 10-12% protein. Usually an adult horse will get plenty of protein from a good-quality grass. I am a strong advocate of mixed legume/grass hay, or legume/grass pasture. I don't think straight alfalfa or clover is good for horses; it's too rich. A mix will usually meet their needs." A hard-working horse needs a little more protein than an idle horse to make up for the wear and tear of work. He breaks down muscle cells, with a higher rate of turnover. But this does not mean he needs a higher percent of total protein in his diet. He will be eating more total feed than an idle horse to supply his increased energy needs, and since most feeds contain protein, he will automatically get the increase in protein necessary to replace and repair any cells damaged during exertion. "Many horsemen feed 12-14% protein supplements, in addition to a high-protein alfalfa hay diet," says Porr. "These horses are getting way more protein than they need. Recent research shows that horses doing an intense level of work can get by on 8-10% protein, as long as it is good quality." Excess Protein--Detrimental and Wasteful In some instances, supplements are needed--if the basic diet is low in protein or lacks high-quality protein for the young horse. But protein is far more often overfed than underfed. "In mature horses, excess protein is often just wasteful, but in young, growing horses imbalances are one of the things that lead to developmental problems," says Porr. "We can't say it's all due to too much protein or too much calcium, but to the ways various nutrients interact with each other." When you overfeed any nutrient, you are more apt to upset the balance and might create problems like developmental orthopedic diseases, which includes several skeletal problems in growing foals. "The thing that scares me most about supplements is when people feed single amino acids," says Ralston. "I was advising one high-level competitor whose horses were tying-up, and found she was feeding a cup of lysine powder daily. She'd heard lysine was good, but this huge amount was causing great amino acid imbalance." Many horse owners feed high-protein diets to hard-working horses, but this is a very inefficient, expensive energy source (protein is one of the more expensive feed ingredients), and it can also be detrimental to a horse which must work hard in hot weather. There is heat produced during protein metabolism, in which extra protein is converted to energy. "An amino acid is basically a string of carbons, with an ammonia group and a carboxyl group on one end," explains Ralston. "If you take that nitrogen-containing (ammonia) segment off many amino acids, they become carbohydrates." Thus a protein not needed by the horse can be broken down into carbohydrates, which can be used as energy. But that chopped-off amino group then has to be excreted as urea or ammonia--which gives urine its ammonia smell, says Ralston. Porr adds, "The body uses the carbons to build fat, and excretes the nitrogen. It ends up as ammonia in urine, wasted on the ground." The body can use protein as energy, says Geor, "but this is an inefficent process; it prefers to use glucose and fat. Protein should be fed to build the engine, not to fuel it. A phrase that sums up protein is 'use it or lose it.' In contrast to glucose or fat in the diet that the body can store, protein can't be stored to any great extent. It is used to build tissue or for the myriad of enzyme systems, but if the protein level in the diet is above what the current needs are, the body excretes it." This process leads to increased water requirements, an important consideration for horses training or competing in hot weather, adds Geor. "You also get into heat increment problems," he says. The process of chopping off the ammonia group releases heat, and the body must try to dissipate the extra heat created. Studies done for the 1996 Olympics showed that any diet over 14% protein can cause heat dissipation problems when horses are working in heat and humidity. "In hot weather, use grass hay instead of legumes, and avoid protein supplements," advises Ralston. Some horse owners feed extra protein in the winter to create more body heat. "I prefer to feed more fiber," says Ralston. The fibrous component of hay releases a fair amount of heat during fermentation breakdown in the hindgut. "Heat of fermentation, from breakdown of fiber, is not as potentially detrimental in summer as the heat increment in protein, because it is not created in the muscles," Ralston adds. "In winter, heat of fermentation helps keep a horse warm--and you don't have the increased ammonia excretion to foul up barn air quality. I can walk into a barn and tell if the horses are being fed too much protein, just from the smell." The horse must urinate more to excrete the by-products of protein metabolism, and therefore must drink more water. For horses in barns, this creates more soiled bedding, and increases lung irritation due to the ammonia. "There are still some myths about protein," says Geor, such as it damaging the kidneys. Horse owners in earlier years probably thought the increase in urine and stronger ammonia smell was an indication of kidney problems. Owners need to realize that excess protein, per se, does not damage the kidneys; it is merely inefficient and wasteful. As long as a healthy horse has access to water, he will not suffer kidney damage. An older horse with compromised kidney function could have trouble on a high-protein diet, however, since he has a harder time filtering and excreting it. The equine nutrition research group at Virginia Tech headed by David Kronfield, BVSc, MVSc, BSc, DSc, PhD, has looked at the amount of protein needed in a ration, both for growing horses and horses in athletic training. They tried to be more precise in how much of any given amino acid is needed for meeting a nutritional target without being wasteful, says Geor. "They fed lower-protein diets with added amino acids, using lysine and threonine. The horses in these studies performed fairly well in comparison to horses on more traditional, slightly higher crude protein diets," he says. Environmental interests are starting to look at horse manure (just as they are looking at cow and pig manure) in terms of how these animals are fed and which nutrients are going on through--and what impact this has on the environment, says Geor. "This may become important for horse management. There needs to be more study in that area, but this could be a workable approach--to feed specific amino acids that meet certain requirements of the horse. This would allow us to be a little more conservative in how much total protein we have to feed." DIETARY PROTEIN REQUIREMENTS OF HORSES CLASS OF HORSE CRUDE PROTEIN (%) RECOMMENDED IN DIET* Weanling at four months 14.5 Weanling at six months 14.5 Yearling (12 months) 12.6 Long yearling (18 months, not in training) 11.3 Long yearling (18 months, in training) 12.0 2-year-old (not in training) 10.4 2-year-old (in training) 11.3 Mature horse--maintenance (idle) 8.0 Mature horse in light work (i.e., pleasure riding) 9.8 Mature horse in moderate work (i.e., jumping, cutting, ranch work) 10.4 Mature horse in intense work (i.e. racing, polo, endurance) 11.4 Stallion 9.6 Pregnant mare, first nine months 10.0 Pregnant mare, 9th and 10th months 10.0 Pregnant mare, 11th month 10.6 Nursing mare, first three months 13.2 Nursing mare, from third month on 11.0 * Dry matter basis; compiled from the National Research Council's Nutrient Requirements of Horses, 5th edition.