* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download F factor conjugation is a true type IV secretion system

Cell nucleus wikipedia , lookup

G protein–coupled receptor wikipedia , lookup

Protein phosphorylation wikipedia , lookup

Endomembrane system wikipedia , lookup

Signal transduction wikipedia , lookup

Magnesium transporter wikipedia , lookup

Intrinsically disordered proteins wikipedia , lookup

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of proteins wikipedia , lookup

Protein moonlighting wikipedia , lookup

Type three secretion system wikipedia , lookup

Protein–protein interaction wikipedia , lookup

Artificial gene synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Western blot wikipedia , lookup

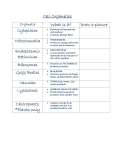

FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 www.fems-microbiology.org MiniReview F factor conjugation is a true type IV secretion system T.D. Lawley, W.A. Klimke, M.J. Gubbins, L.S. Frost Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada T6G 2E9 Received 18 March 2003; received in revised form 15 May 2003; accepted 16 May 2003 First published online 14 June 2003 Abstract The F sex factor of Escherichia coli is a paradigm for bacterial conjugation and its transfer (tra) region represents a subset of the type IV secretion system (T4SS) family. The F tra region encodes eight of the 10 highly conserved (core) gene products of T4SS including TraAF (pilin), the TraBF , -KF (secretin-like), -VF (lipoprotein) and TraCF (NTPase), -EF , -LF and TraGF (N-terminal region) which correspond to TrbCP , -IP , -GP , -HP , -EP , -JP , DP and TrbLP , respectively, of the P-type T4SS exemplified by the IncP plasmid RP4. F lacks homologs of TrbBP (NTPase) and TrbFP but contains a cluster of genes encoding proteins essential for F conjugation (TraFF , -HF , -UF , -WF , the C-terminal region of TraGF , and TrbCF ) that are hallmarks of F-like T4SS. These extra genes have been implicated in phenotypes that are characteristic of F-like systems including pilus retraction and mating pair stabilization. F-like T4SS systems have been found on many conjugative plasmids and in genetic islands on bacterial chromosomes. Although few systems have been studied in detail, F-like T4SS appear to be involved in the transfer of DNA only whereas P- and I-type systems appear to transport protein or nucleoprotein complexes. This review examines the similarities and differences among the T4SS, especially F- and P-like systems, and summarizes the properties of the F transfer region gene products. = 2003 Federation of European Microbiological Societies. Published by Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords : Conjugation; Plasmid; Type IV secretion ; Pili; Membrane complex 1. Introduction In 1946, Joshua Lederberg proposed that a ‘‘cell fusion would be required’’ to facilitate the transfer of F factor DNA, integrated in the chromosome of the donor cell, into recipient Escherichia coli [1]. We now know that this cell fusion is constructed by the type IV secretion system (T4SS) encoded on Gram-negative conjugative elements. T4SS, also known as the mating pair formation (Mpf) apparatus, are central to the dissemination of numerous genetic determinants between bacteria, as highlighted by the spread of antibiotic resistance among pathogens [2,3]. T4SS are cell envelope-spanning complexes (11^ 13 core proteins) that are believed to form a pore or channel through which DNA and/or protein travels from the cytoplasm of the donor cell to the cytoplasm of the recipient cell. T4SS have also been found to secrete virulence factor proteins directly into host cells as well as take * Corresponding author. Tel. : +1 (780) 492-0672; Fax : +1 (780) 492-9234. E-mail address : [email protected] (L.S. Frost). up DNA from the medium during natural transformation, revealing the versatility of this macromolecular secretion apparatus [4,5]. Despite the clinical and evolutionary importance of T4SS, the general mechanism by which they secrete or take up macromolecules remains unknown. The F factor remains a paradigm for understanding the mechanism by which T4SS transfer macromolecules across the membranes of Gram-negative bacteria [6^8]. DNA transfer occurs within the tightly appressed cell envelopes of mating cells, which are referred to as conjugation junctions [9^11]. These junctions form in the presence of the Mpf or T4SS proteins; the same proteins that assemble pili (Figs. 1 and 2 ; Table 1) and transfer DNA. Conjugation is thought to be initiated by contact between the F-pilus and a suitable recipient resulting in pilus retraction [12] and stable mating pair or aggregate formation [9]. Prior to the initiation of DNA transfer, the relaxosome, consisting of proteins bound to the origin of transfer (oriT), resides within the cytoplasm of donor cells [13]. A mating signal, possibly generated by contact between the pilus and recipient cell, appears to result in a speci¢c interaction between the relaxosome and the coupling protein, or nucleic acid pump, at the inner face of the con- 0378-1097 / 03 / $22.00 = 2003 Federation of European Microbiological Societies. Published by Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00430-0 FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 2 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 Fig. 1. Comparison of F-like T4SS with each other and with P- and I-like T4SS. Transfer genes are presented with color/pattern, with the same color/ pattern representing homologous gene products (see Table 1), while non-essential transfer genes are white. Light gray genes represent transfer gene products with no shared homology to other T4SS subfamilies. Lipo = lipoprotein motif ; band within arrow = Walker A motif; upper case gene names = Tra; lower case gene names = Trb (F, pNL1 and RP4) or Trh (R27). Double slash indicates non-contiguous regions. The gene sizes are relative to each other. Maps were produced using the indicated GenBank accession numbers: F-NC_002483; pED208-AY046069 ; R27-NC_002305; Rts1NC_003905; pNL1-NC_002033; R391-AY090559; SXT-AY055428; RP4-NC_001621; R64-AB027308. See text for details and references. jugative pore [14,15]. Coupling protein^relaxosome contact could lead to DNA unwinding, generating a single strand of DNA that is then transferred to the recipient in a 5P to 3P direction [16^18]. This two-step mechanism has been proposed to result in the transport of the relaxase, covalently bound to the 5P end of the transferring strand (T-strand), into the recipient through the T4SS conjugative pore [19]. The detection of the relaxase in the recipient has as yet not been successful, however, the topological constraints of DNA transfer combined with the role of the relaxase in termination makes this highly probable. Considerable circumstantial evidence supports the transfer of a pilot protein, such as the relaxase, along with the DNA. The most compelling is the indirect evidence for transport of a primase, encoded as a domain of the relaxase protein by the IncQ mobilizable plasmid R1162, that could initiate replacement DNA strand synthesis in the new transconjugant [20]. Interestingly, the IncP and I conjugative systems also transport primase molecules either alone or in conjunction with the DNA [21,22], suggesting an evolutionary relationship with the IncQ system. The transport of the VirD2^T-DNA com- FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 3 Fig. 2. A representation of the F-like T4SS transfer apparatus drawn from available information. The pilus is shown assembled with ¢ve TraA (pilin) subunits per turn extending from the inner membrane through a putative secretin-like outer membrane pore involving TraK. TraK is anchored by TraV and interacts with TraB in the inner membrane. TraB interacts with the coupling protein creating a continuous pore from the cytoplasm through the cell envelope to the extracellular environment. Other components of the inner membrane and periplasm are indicated, with TraL and TraE seeding the site of pilus assembly and attracting TraC to the pilus base where it acts to drive assembly in an energy-dependent manner. The Mpf proteins include TraG and TraN that aid in mating pair stabilization (Mps). TraF, -H, -U, -W and TrbC, together with TraN, are speci¢c to F-like systems and might have a role in pilus retraction, pore formation and mating pair stabilization. plex from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to wounded plant tissue to initiate crown gall formation is another example of a relaxase-like protein bound to the 5P end of a singlestranded DNA molecule being transported via a T4SS [23^25]. Thus it is not impossible to think of conjugative DNA transfer as a protein transport system that has been modi¢ed to transfer DNA along with a protein substrate. The core T4SS proteins in F, TraAF (pilin), -LF , -EF , -KF , -BF , -VF , -CF and -GF (N-terminal domain), also require the auxiliary, essential gene products TraFF , -GF (C-terminal domain), -HF , -NF , -UF , -WF and TrbCF for pilus assembly and mating pair stabilization. Additional essential gene products in the F conjugative system include the coupling protein, TraDF , and the members of the relaxosome, TraIF , a relaxase^helicase bifunctional protein, TraMF , and TraYF that are required for DNA transfer. TraBF along with TraCF are the quintessential T4SS proteins and are the easiest to ¢nd homologs for in BLAST searches. Similarly, the coupling protein (e.g. TraDF ) is the signature homolog of conjugative T4SS systems capable of nucleic acid transport [19], whereas TrbBP /VirB11Ti /TraJI homologs are indicative of P-type/ Ti/I-type systems [26]. The auxiliary genes present in F (encoding TraFF , -GF (C-terminal domain), -HF , -NF , -UF , -WF and TrbCF ) are conserved throughout F-type systems and serve as hallmarks of this family. These gene products are essential for F transfer and appear to be involved in pilus retraction and mating pair stabilization, which are critical factors for e⁄cient F conjugation in liquid media. The conjugative ability of P-type systems, which lack these homologs, is lower in liquid media than on solid media and may re£ect the di¡erent ecological niches inhabited by bacteria carrying the F- and P-type transfer systems [27]. The proteins involved in conjugal DNA metabolism as well as those involved in the regulation of gene expression or the prevention of conjugation between donor cells (surface and entry exclusion, TraTF and -SF , respectively) will not be discussed here. The interested reader is directed to reviews by Lanka and Wilkins [28], Lawley et al. [8], Llosa et al. [19] and Zechner et al. [18]. This review will discuss the essential T4SS proteins in F-type systems (IncF, IncHI, IncJ, IncT and the SXT element, among others), which di¡er in signi¢cant ways from P-type systems such as that of RP4 (IncP), Ptl (Bordetella pertussis toxin excretion system) and VirB (Ti plasmid tumorigenesis system of A. tumefaciens) T4SS [2,4] (see below). A third system, the I-type, about which relatively little is known, is exempli¢ed by the IncI plasmid T4SS that have signi¢cant homology to the virulence factor transport systems of Legionella pneumophila [29^31]. 2. F-like T4SS components The essential components of the F-like T4SS are de¢ned as those Mpf proteins that are essential for conjugation, as determined by mutagenesis and complementation experiments of both the F factor and the IncHI1 plasmid R27 [7,32^34]. Results obtained from investigations into individual Mpf proteins from both the F factor and the R27 T4SS are combined to create an F transfer protein family FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 4 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 Table 1 Summary of conserved F-like T4SS components Proteina P-type homologd I-type homologd Size rangee Signal (aa) sequencef Cellular Motifsh g location(s) TraX 112^128 93^105 130^261 299^410 429^475 171^316 799^893 912^1329 Y N Y Y N Y N N IM, E IM IM/P P/OM IM/P OM IM IM/P 150^368 210^502 203^254 330^358 602^1230 N Y Y Y Y IM P P P OM TraF 257^363 Y P TraH Orf169 TrbB 453^501 169^265 230^298 Y Y Y OM IM P TraA TraL TraE TraK TraB TraV TraC TraG TrbC/VirB2 TrbD/VirB3 TrbJ/VirB5 TrbG/VirB9 TrbI/VirB10 TrbH/VirB7 TrbE/VirB4 TrbL/VirB6 TrhPb TraWc TrbC TraU TraN TraF TraN TraO TraI TraU TrbB Proposed function Pilin Pore Pore Secretin Pore Coiled-coil Pore Lipoprotein Pore ATPase Secretion Mating pair stabilization ; pore Peptidase Transfer peptidase Pore Pore DNA transfer Cysteine-rich Mating pair stabilization ; adhesin Disul¢de Disul¢de bond isomerase formation Coiled-coil Pore Lysozyme Transglycosylase Disul¢de Disul¢de bond isomerase formation Interacting partners in F- and P-like T4SSi Interaction reference TraXF , TraQF TrhCH TrhCH TraBF , TraVF TraKF , TrhCH ,, TraGH TraKF TrhBH , TrhEH , TrhLH TraSF [41] [34] [34] [40] [34,40] [40] [34] [2] TrbC TraW Components in bold indicate homology to P-like T4SS. a Nomenclature according to the F system except for the peptidase TrhP which is named according to R27 nomenclature. The R27 transfer protein nomenclature is Trh [33,34]. The P- and I-type nomenclature is according to Christie [2]. b R27, Rts1, R391, SXT and pNL1 systems contain a peptidase with the peptidase of pNL1 containing an N-terminal fusion to TrbI, suggesting a coupled function. F and pED208 do not contain peptidases. c In R27, Rts1, R391 and SXT systems TrbC is fused to the N-terminus of TraW, suggesting a coupled function, whereas they are separate proteins in F and pED208. d Homology deduced based on similarity identi¢ed with PSI-BLAST analysis or functional analogy. e Range is determined by comparing homologs in F, pED208, R27, Rts1, R391, SXT and pNL1. f Signal sequence predicted with SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP). g Inner membrane (IM), periplasm (P), outer membrane (OM) and extracellular (E). h Motifs identi¢ed with ScanProsite (http://ca.expasy.org/tools/scanprosite/), CDD (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) or Coils (http://www.ch. embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html). i Transfer system in which direct or indirect interaction identi¢ed is indicated with subscript. in this overview, as it is likely that homologs are functionally equivalent. Based on work on the F factor, the T4SS proteins are organized according to three proposed functions : (1) pilin and pilin processing, (2) pilus tip formation and pilus extension and (3) mating pair stabilization [7] (Figs. 1 and 2; Table 1). Other non-essential components of F-like T4SS are TraP, a protein that stabilizes the extended pilus; TrbB, a putative thioredoxin homolog ; TrbI, a protein which promotes DNA transport and has homology to the FliK £agellum assembly protein (L.S. Frost, unpublished results); and Orf169, a lytic transglycosylase with homologs in P- and I-like systems. 2.1. F-like propilin processing The propilin subunits from F-like T4SS ranges in size from 112 to 128 aa (Table 1). The pilin subunit is poorly conserved among T4SS, for example the pilin subunit of the R27 (TrhAH ) shares more similarity with the IncP pilin (TrbCP ) than with the IncF pilin (TraAF ) [34]. All F-like propilin subunits contain a long leader sequence that is either known or predicted to be cleaved by the host leader peptidase, LepB, to produce a peptide of 68^ 78 aa [35,36]. After removal of the signal sequence, the F-pilin subunit is oriented in the inner membrane with its N- and C-termini positioned in the periplasm [37,38]. Indeed, all pilin subunits of the F-type T4SS appear to contain two hydrophobic regions that serve as transmembrane regions. The correct insertion and accumulation of F-pilin in the inner membrane requires the chaperone-like inner membrane protein, TraQ, which is present only in T4SS closely related to F itself [39]. Pilin subunits typically undergo an additional processing reaction, which has been identi¢ed as acetylation by TraXF in F-like pilins (F, R1, R100-1, pED208) [39^41] or cyclization by the peptidase TraFP in P-like pilins (RP4 and Ti) [42]. The propilin subunits of R27, Rts1, R391, SXT and pNL1, which are encoded by F-like T4SS, are more similar to P-like pilins. They are likely cleaved at the C-terminus and possibly cyclized by a transfer peptidase/cyclase, although this has yet to be demonstrated. Pilin insertion into the membrane and maturation are FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 the ¢rst steps in pilus production. Assembly of conjugative F-like pili on the bacterial surface requires the remainder of the T4SS and the auxiliary gene products, except for the C-terminal domain of TraG, TraN and TraU. F-pilin subunits are stored as a pool in the inner membrane prior to assembly on the cell surface [43]. Pili are assembled by addition of pilin subunits to the base of the pilus, as demonstrated by H-pili of R27 [44]. In response to contact with a suitable recipient, pilus retraction appears to proceed in an energy-independent manner [40], which is the reverse of assembly, whereby the pilin subunits return to the membrane and possibly serve to stabilize the mating pair or be a part of the conjugative pore. Homology studies have revealed that the pilin gene appears to have been shu¥ed among various T4SS during evolution. For example, the IncHI1 plasmid, R27, has an F-like T4SS except for a P-like pilin protein and corresponding peptidase/cyclase [34]. The lack of sequence conservation in pilin could be due to: (1) rapid evolution of the pilin subunits in response to strong selective forces of extracellular factors such as phage and receptors on recipients and (2) lateral gene transfer of F-, P- and I-like propilin and processing genes between T4SS subfamilies. In fact, the cassette-like nature for the development of the T4SS is striking and suggests that there has been considerable opportunity for ‘mix and match’ during evolution. 2.2. F-like T4SS pilus assembly Mutations in traL, -E, -K, -B, -V, -C, -W, -F, -H, and the 5P end of traG have broadly similar phenotypes, which include the inability to assemble pili and transfer DNA [7]. Using a sensitive M13K07 transducing phage assay, Anthony et al. [32] identi¢ed two mutant subgroups that are consistent with two steps in pilus assembly : (a) those mutations that prevent pilus tip formation on the cell surface (in traL, -E, -K, -C, -G) and (b) those that allow tip formation but block pilus extension (traB, -V, -W, -F, -H). These results provided the ¢rst example in any T4SS of a di¡erentiation of roles for Mpf proteins. The F-like T4SS components will be organized according to these results. 2.2.1. Pilus tip formation 2.2.1.1. TraLF . Members of the TraLF family range in size from 93 to 105 aa and are homologous to TrbDP (103 aa) and VirB3Ti (108 aa) [45]. TraL is predicted to localize to the inner membrane, as is TrbDP [46]. In F, TraLF has never been visualized, suggesting it could be the limiting factor determining the number of F-pili per cell. TrhLH , along with TrhEH and TrhBH , of R27 (IncHI1) was shown to be essential for the formation of TrhCH complexes, indicating either a direct or an indirect interaction between TrhLH and TrhCH [47]. 2.2.1.2. TraEF . TraEF family members range in size 5 from 130 to 261 aa and are homologous to TrbJP (258 aa) and VirB5Ti (220 aa) [7]. TraEF and TrbJP are predicted to be located in the inner membrane (RP4) [7,46] whereas VirB5Ti is thought to be a minor component of the T-pilus [48]. 2.2.1.3. TraKF . The TraKF family of proteins range in size from 299 to 410 aa and are homologous to TrbGP (297 aa), VirB9Ti (293 aa) and TraNI (327 aa) [7]. TraKlike proteins are predicted to be located in the periplasm or outer membrane [7,46,49]. This protein family shares similarity to secretin proteins, especially the HrcC subgroup of the type III secretion system (T3SS) encoded by Pseudomonas syringae [50] (Fig. 3). The C-terminal regions of TraKF proteins are conserved in both the L-domain and S-domain of the prototypical secretin PulD of Klebsiella oxytoca [34]. The L-domain is present in all secretins and is proposed to be embedded within the outer membrane to form the ring structure typical of secretins. The S-domain is a region of 60 aa that binds to a lipoprotein which serves as a periplasmic chaperone [51]. The C-terminus of TraKF has been shown to interact with TraVF , a lipoprotein, and the N-terminus of TraKF interacts with TraBF , an inner membrane protein [49]. The TraBF -TraKF -TraVF complex likely forms an envelopespanning structure similar to that of VirB10-VirB9-VirB7 of the Ti plasmid T4SS [52]. Although TraKF is a periplasmic protein, it associates with the outer membrane in the presence of the F T4SS [49]. The presence of a putative secretin within the T4SS suggests a mechanism by which both the pilus and DNA could transverse the outer membrane. 2.2.1.4. TraCF . Members of the TraCF family of proteins range in size from 799 to 893 aa and are homologous to TrbEP (852 aa), VirB4Ti (788 aa) and TraUI (1014 aa). TraCF is predicted to be a peripheral inner membrane protein whose localization is dependent upon the presence of the T4SS, speci¢cally TraLF [47,53]. All members of this protein family contain both Walker A and Walker B motifs, which energize pilus assembly [54,55]. A point mutation in traCF , traC1044, is a temperature-sensitive mutation that blocks pilus assembly [56]. Using TrhCGFP fusions, TrhCH of R27 was shown to form complexes in the inner membrane, possibly containing other transfer proteins. The formation of TrhC-GFP complexes was dependent on the presence of TrhBH , -EH and -LH , suggesting either a direct or an indirect interaction between these proteins [47]. 2.2.1.5. TraGF . TraGF proteins range in size from 913 to 1329 aa. TraGF proteins have two roles in conjugation: the N-terminal region is involved in pilus tip formation and pilus assembly whereas the entire protein is involved in mating pair stabilization [57] (see below). The N-terminal 500^600 aa is proposed to be localized to the inner FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 6 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 VcoSXTTraK PreR391TraK 2.2.2. Pilus extension 100 SmeHtdP PvuRts1TraK StyR27TrhK 100 84 89 NarpNL1TraK StypED208TraK 70 100 100 100 100 PsysyringaeHrpH 58 100 PsytomatoHrcC StyR100TraK EcoFTraK EcoColB2TraK StypSLTTraK 100 86 99 PcaHrcC PchHrcC PflRscC PstHrcC EamHrcC 500 changes Fig. 3. Phylogenetic analysis of T4SS secretin-like proteins of the TraKF family with the HrcC T3SS secretin family. A PSI-BLAST search of the non-redundant bacterial database was used to generate the alignment. The expect size was 100^1000 with gap open and gap extension penalties of 7 and 2, respectively. The sequences were multiply aligned using ClustalX with a Gonnet matrix; gap open and gap extension penalties were set within the range 4^10 and 0.2^0.5, respectively. Sequences with very little divergence were discarded and the multiple alignment was imported into MacClade v4.0 to generate a *.nexus ¢le. Phylogenetic analysis was carried out with the PAUP 4.0 beta 8/10 software package using parsimony and a heuristic search of 100 replicates with the PAM250 (modi¢ed matrix) character type. Once a ¢nal tree was selected, it was bootstrapped through 100 replicates to give the consensus values shown. The various homologs are listed on the tree using a three-letter abbreviation for the bacterial host, followed by the plasmid name (if applicable) and the gene or protein name. The following list comprises all of the relevant information in the homology tree in the following format: three-letter bacterial species abbreviation, plasmid name (if applicable), gene or protein name, accession number, full bacterial species name. Pre R391 TraK AAM08021 P. rettgeri; Vco SXT TraK AAL59718 V. cholerae ; Pvu Rts1 orf209 BAB93771 P. vulgaris; Nar pNL1 TraK NP_049166 N. aromaticivorans; Psy_syr HrpH AAC05014 P. syringae pv. syringae; Psy_tom HrcC AAC34756 P. syringae pv. tomato ; Pca HrcC AAK97280 Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum ; Pch HrcC AAC31975 Pectobacterium chrysanthemi ; Eam HrcC AAB49179 Erwinia amylovora; Pst HrcC AAG01463 Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii ; P£ RscC AAK81929 Pseudomonas £uorescens; Sty pSLT TraK NP_490566 S. typhimurium; Eco ColB2 TraK AAB07774 E. coli; Eco F TraK AAC44189 E. coli ; Sty R100-1 TraK AAB07769 S. typhi; Sty pED208 TraK AAM90706 S. typhi ; Sty R27 TrhK AAD54050 S. typhimurium ; Sme R478 HtdP AAL27020 Serratia marcescens. membrane and contains six to eight transmembrane regions whereas the remaining C-terminal region is located within the periplasmic space (unpublished results). The N-terminal domain is homologous with TrbLP (528 aa) and VirB6Ti (295 aa), both of which are also predicted to contain multiple transmembrane regions and are essential for pilus biosynthesis (Fig. 4). 2.2.2.1. TraBF . Members of the TraBF protein family range in size from 429 to 475 aa and are homologous to TrbIP (463 aa), VirB10Ti (377 aa) and TraOI (429 aa) within their C-terminal regions (Fig. 5). Limited homology also exists among all these homologs with FliF, a structural protein in the type III secretion system involved in £agellum assembly (L.S. Frost, unpublished observations) [58]. TraBF -like proteins are predicted to contain an N-terminal anchor with the bulk of the protein located within the periplasm. The N-terminal region of F-like TraB proteins contain coiled-coil domains, which are probably involved in multimerization, and a proline-rich domain, suggesting an extended structure [59]. The proline-rich domain, by analogy with other such motifs, could interact with SH3 domains in other proteins, an interaction central to signal transduction [60]. TrhBH of R27 was recently shown to interact with itself and with the coupling protein TraGH [59] providing exciting evidence that the T4SS and the coupling protein (in F, TraDF ) do, indeed, ‘couple’, linking the relaxosome to the T4SS. 2.2.2.2. TraFF . The TraFF protein family ranges in size from 257 to 363 aa and shares homology to TrbBF (a non-essential, conserved, F-like T4SS component) and TrbBI of the IncI transfer system; there is no known homolog in P-like systems. These proteins share similarity to the thioredoxin superfamily, characterized by the C-X-XC motif and the thioredoxin fold (Elton et al., in preparation). Since TraF is localized to the periplasmic space, these proteins likely play a role in thiol redox chemistry within the periplasm, possibly involving disul¢de bond formation or isomerization. It is interesting to note that several T4SS components localizing to the periplasm contain multiple, conserved cysteine residues including homologs of TraBF , -PF and -GF (2), TraHF and -VF (3), TraUF (10) and TraNF (22) with homologs of TrbIF having a single conserved cysteine [8,61]. In addition, members of this protein superfamily have also been proposed to act as chaperones that prevent inappropriate interactions with other proteins [62]. In light of these observations, perhaps TraFF - and TrbBF -like proteins are key to the disul¢de bond chemistry in F-like T4SS assembly. 2.2.2.3. TraHF . TraHF -like proteins range in size from 453 to 501 aa and are unique to the F-like T4SS subfamily. Members of the TraHF protein family are localized to the periplasm/outer membrane [63] and contain C-terminal coiled-coil domains, suggesting the formation of higher order structures, either with other TraHF molecules or with other components of the T4SS. 2.2.2.4. TraWF -TrbCF . Members of the TraWF protein family range in size from 210 to 502 aa and are unique to the F-like T4SS subfamily. TrbC is fused to the N-ter- FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 minus of TraW in R27, Rts1, R391 and SXT, whereas TraW and TrbC are separate proteins in F, pED208 and pNL1. The fusion of TrbCF to TraWF suggests that the functions of these proteins are linked. Both proteins are proposed to be localized to the periplasmic space. TrbCF is correctly processed in the presence of TraNF suggesting a relationship between these two proteins, which are encoded on adjacent genes in the F tra operon [64]. 2.2.2.5. TraVF . TraVF -like proteins range in size from 171 to 316 aa and are lipoproteins with a signature cysteine at the processing site [65]. Although TraVF proteins share little similarity to TrbHP (160 aa), VirB7Ti (55 aa) or TraII (272 aa) beyond two conserved cysteines thought to be involved in multimerization, they appear to be functional analogs that interact with secretin-like proteins such as TraKF and VirB9Ti . Indeed, TraVF has been shown to interact with TraKF , a putative secretin [49], and VirB7Ti is known to interact with VirB9Ti [66,67] 2.2.3. Mating pair stabilization Mating pair stabilization is a unique feature of F-like T4SS and is believed to be at least partially responsible for facilitating DNA transfer in liquid environments. Based on the experimental evidence of Kingsman and Willetts [68] and recent evidence involving TraGF in recognition of the TraSF entry exclusion protein (L.S. Frost, unpublished results), mating pair stabilization might involve building a structure between the two cells that ‘staples’ them together. Mating pairs are di⁄cult to break apart prematurely and require signi¢cant force to do so. However, about 30 min after the start of F plasmid transfer, the cells spontaneously separate suggesting an active mechanism involving the expression of genes in the new transconjugant, previously identi¢ed as being in the distal part of the F tra operon [69]. Candidates for mating pair separation include the entry and surface exclusion proteins TraSF and TraTF as well as the relaxase (TraIF ) and coupling protein (TraDF ), which might generate a break in DNA transport signalling the termination of conjugation. 2.2.3.1. TraGF . The whole of TraGF , but especially the C-terminal region, is involved in mating pair stabilization. In F T4SS, the C-terminal region is fused to a homolog of TrbLP /VirB6Ti suggesting that these homologs might be involved in forming a conjugative pore with varying degrees of sturdiness. This region is predicted to be located within the periplasmic space and has been proposed to interact with TraNF to stabilize mating pairs [57]. A second C-terminal product TraG*, which is believed to be a cleavage product of the full-length protein, has been detected in the periplasm [57] although its importance in transfer is in doubt (L.S. Frost, unpublished results). TraGF is involved in entry exclusion, a process by which DNA synthesis and transport from the donor cell is blocked by TraSF in the inner membrane of the recipient 7 cell. TraGF could be translocated to the recipient cell where it would interact with TraSF instead of its true receptor. TraGF is plasmid-speci¢c for TraSF and this speci¢city maps to a central C-terminal domain of TraGF (L.S. Frost, unpublished observation). If homologs of TraGF are involved in mating pair junction formation, it suggests that the periplasmic space of the donor cell contracts bringing the inner and outer membrane together. In P-type systems, the TrbLP /VirB6Ti homologs might not be able to penetrate the cell envelope of the recipient cell, a function of the pilus, whereas the C-terminal domain of TraGF homologs reaches all the way to the inner membrane of the recipient to stabilize the pilus penetration event. 2.2.3.2. TraNF . TraNF -like proteins are 602^1230 aa and are unique to F-like T4SS; they are signature proteins for the auxiliary class of T4SS that de¢ne the F-like subfamily [70]. This family of proteins appear to act as ‘adhesins’ based on evidence for TraNF which is present in the outer membrane of donor cells. TraNF of the F plasmid interacts with the major outer membrane protein OmpA in recipient cells to stabilize the mating pairs prior to DNA transfer. Other F-like TraNF proteins do not necessarily interact with OmpA, for instance, TraNR100 of the F-like R100 plasmid does not share this receptor. The N- and C-terminal regions of TraNF proteins are highly conserved whereas the central region displays extensive divergence. It is this central region that is involved in OmpA recognition by TraNF as well as TraNF multimerization [71]. Preliminary evidence suggests that TraNF and TraVF interact since some mutants of traN are destabilized in the absence of traV [70]. 2.2.3.3. TraUF . Members of the TraUF protein family range in size from 330 to 358 aa and are unique to the F-like T4SS subfamily. TraUF is a periplasmic protein that is essential for DNA transfer but not formation of conjugative pili, as 20% of donors containing F traU mutations produce pili. TraUF is therefore proposed to be primarily involved in DNA transfer perhaps by aiding mating pair stabilization and conjugative pore formation since mutations in traU, -G and -N have the same phenotype [72]. 3. Relationships between F- and P-type T4SS It has been long been recognized that there are two types of conjugative pili: long, £exible pili and short, rigid pili [27]. It is now evident that long, £exible pili are encoded by F-type T4SS (IncF, -H, -T, -J) whereas short, rigid pili are encoded by P-type T4SS (IncP, -N, -W, -I). The long, £exible pili produced by F-like T4SS measure 2^ 20 Wm and have a diameter of 8 nm with a central lumen measuring 2 nm. The pilin subunits are arranged as a he- FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 8 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 lical array. F-pili are easily seen attached to cells and appear £exible in electron micographs. The short, rigid pili produced by P-like T4SS are seldom seen attached to donors. They measure 8^12 nm in diameter [42] and are usually under 1 Wm in length. No information on the arrangement of the circular subunits in the assembled pilus is currently available for P-like pili. The di¡erences in pilus structure are not likely dictated by di¡erences in pilin processing, such as acetylation or cyclization, since acetylase and transfer peptidase coding regions can be present in Atu pAT VirB6 Atu pAT AvhB6 Ret VirB6 Sme pSymA VirB6 Lpn LvhB6 Lpn LvhB6 Xax pXA64 VirB6 Ppu pWWo MpfE pIPO2T TraH Sme pSB102 TraH Xca VirB6 Xca VirB6 Xca VirB6 Xca VirB6 Xax VirB6 Xax VirB6 Rrh pRi1724 riorf158 Atu pTiAB2 VirB6 Atu pTi VirB6 Atu pTiC58 VirB6 Atu pRiA VirB6 Atu pTi VirB6 Hpy jhp0033 Hpy orf1 Rrh pRi1724 riorf124 Atu pRiA4b TrbL Rrh pNGR234a TrbL Atu pTi AGR_pTi_76p Atu pTiSakura tiorf11 Atu pTi TrbL Psp pADP1 TrbL Cte pTSA TrbL Eae R751 TrbL Psp pB4 TrbL RK2 TrbL Xfa pXF51 Xfa0037 Mlo mlr6402 Mlo TrbL Mlo pMLb m119606 Rso TrbL Sen pHCM1 HCM1.262 Sty R27 TrhG Sfl R100 TraG Eco F TraG Sty pSLT TraU Sty pED208 TraG Vco SXT TraG Pre R391 TraG Rco RC0146 Rpr RP108 Eco R388 TrwI Sen SO11 Eco R6K PilX6 Ype pYC orf5 Sty R46 TraD Xfa pXF51 Xfa0011 Mlo pMLa mlr9255 Mlo R71 msi411 Ngo_JC1 TraG Pvu Rts1 orf242 Bhe VirB6 Cac CAC2046 Nar pNL1 TraG Eco R721 TraA Ccr CC2420 Bpe VirB6 Hpy jhp0937 Sco SCD72A.15c Ban pX01 pX01-79 Bf1 hydrophobic protein Cac CAC2403 Bth TraJ Nsp alr7534 FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 both F-like and P-like T4SS. Instead, the di¡erences probably lie with the auxiliary genes in F-like systems or TrbBP in P-like systems, which de¢ne these two groups (see below). Long, £exible pili allow donors to mate in liquid and on solid media with approximately equal e⁄ciencies whereas short, rigid pili result in a surface-preferred mating phenotype [27,73]. Long, £exible pili likely retract and allow mating pair stabilization thereby facilitating mating in liquid media, a property not available to systems with short, rigid pili. Retraction [12,74,75] is reminiscent of type IV pili encoded by type II secretion systems [76,77] and is proposed to occur in response to a ‘mating signal’ received from the pilus tip when it contacts a suitable recipient cell. Other conjugative elements which contain F-type T4SS include, besides the F factor (E. coli) [7], R100 (IncFII) [32], pED208 (IncFV; S. typhi) [39], R27 (IncHI1; S. typhi) [78], Rts1 (IncT; Proteus vulgaris) [79], R391 (IncJ; Providencia rettgeri) [80], SXT element (Vibrio cholerae)[81] and pNL1 (Novosphingomonas aromaticivorans) [82] (Fig. 1). Neisseria gonorrhoeae contains an F-type T4SS that is not used for conjugation, but rather for the secretion of DNA [83]. It is interesting that no F-type T4SS have been reported to secrete virulence factors. In fact, no F-type T4SS to date has been shown to secrete proteins [21]. Conjugative elements that contain P-type T4SS include RP4 (IncPK; Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [84], R751 (IncPL; Klebsiella aerogenes) [85], pKM101 (IncN; Salmonella typhimurium)[86] and R388 (IncW; E. coli; accession num- 9 ber X81123) (see [4]). In many respects, P-type T4SS appear to be capable of transferring/secreting/taking up a broader repertoire of macromolecules. For example, IncP and IncI plasmids are also known to transfer the DNA primases, TraC and Sog, respectively, from donor to recipient cells [21] even in the absence of DNA [22]. As noted earlier, Helicobacter pylori utilizes a subset of the P-type T4SS for DNA uptake [5]. Many pathogens use P-type T4SS to secrete virulence factors into hosts as proteins or nucleoprotein complexes, such as the T-DNA of the Ti plasmid [87], CagA of H. pylori [88^90] and pertussis toxin of B. pertussis [91,92]. It is noteworthy that conjugative plasmids containing the P-type T4SS are broadhost-range (IncP, W and N) [93] whereas F/H-type systems are narrow-host-range. 4. The nature of the conjugative pore The nature of the conjugative pore is the central question in conjugation, as well as in the biology of T4SS. Only recently have we begun to understand how singlestranded DNA can traverse the cell envelopes of both donor and recipient cells (Fig. 2). At the inner face of the conjugative pore are coupling proteins, which are present in all conjugative transfer systems [19]. Coupling proteins are inner membrane proteins that are thought to recruit the cytoplasmic relaxosome complex to the membrane-associated T4SS [94,95] with direct interactions between relaxosomes and coupling proteins having recently 6 Fig. 4. Alignment of a portion of TraGF homologs to illustrate the evolutionary relationship between the N-terminal region of TraGF and members of the VirB6 family. A PSI-BLAST search was performed as described in Fig. 3. Each sequence is labeled as follows: three-letter bacterial species abbreviation, plasmid name (if applicable), gene or protein name. TraG from plasmid F is outlined by a black box. Only the amino acid sequence extending from L298 to K386 of the entire 938-amino acid sequence of TraGF is shown. The following list comprises all of the relevant information in the alignments in the following format: three-letter bacterial species abbreviation, plasmid name (if applicable), gene or protein name, accession number, full bacterial species name. Atu pAT AvhB6 gi16119391 A. tumefaciens; Atu pAT VirB6 gi17938753 A. tumefaciens ; Ret VirB6 gi21492814 Rhizobium etli; Sme pSymA VirB6 gi16263167 Sinorhizobium meliloti ; Lpn LvhB6 gi19919314 L. pneumophila; Lpn LvhB6 gi6249468 L. pneumophila; Xax pXA64 VirB6 gi21264269 Xanthomonas axonopodis; Ppu pWWo MpfE gi18150987 Pseudomonas putida; pIPO2T TraH gi16751940 Broad host range; Sme pSB102 TraH gi15919984 S. meliloti ; Xca VirB6 gi21232730 Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris; Xca VirB6 gi21232726 X. campestris pv. campestris ; Xca VirB6 gi21232559 X. campestris pv. campestris; Xca VirB6 gi21232723 X. campestris pv. campestris; Xax VirB6 gi21243338 X. axonopodis ; Xax VirB6 gi21243338 X. axonopodis; Rrh pRi1724 riorf158 gi10954804 Rhizobium rhizogenes ; Atu pTiAB2 VirB6 gi18033167 A. tumefaciens; Atu pTi VirB6 gi17939305 A. tumefaciens ; Atu pTiC58 VirB6 gi73223 A. tumefaciens; Atu pRiA VirB6 gi3184197 A. tumefaciens; Atu pTi VirB6 gi10955148 A. tumefaciens; Hpy jhp0033 gi15611104 H. pylori; Hpy orf1 gi4185987 H. pylori ; Rrh pRi1724 riorf124 gi10954770 R. rhizogenes; Atu pRiA4b TrbL gi13990978 A. tumefaciens ; Rrh pNGR234a TrbL gi16519692 R. rhizogenes ; Atu pTi AGR_pTi_76p gi16119847 A. tumefaciens; Atu pTiSakura tiorf11 gi10954831 A. tumefaciens; Atu pTi TrbL gi10955098 A. tumefaciens ; Psp pADP1 TrbL gi13937498 Pseudomonas sp. ADP ; Cte pTSA TrbL gi13661668 Comamonas testosteroni; Eae R751 TrbL gi10955221 Enterobacter aerogenes; Psp pB4 TrbL gi19352395 Pseudomonas sp.; RK2 TrbL gi348633 Broad host range; Xfa pXF51 Xfa0037 gi10956748 Xylella fastidiosa; Mlo mlr6402 gi13475356 Mesorhizobium loti; Mlo TrbL gi20803852 M. loti ; Mlo pMLb m119606 gi13488455 M. loti ; Rso TrbL gi17547297 Ralstonia solanacearum; Sen pHCM1 HCM1.262 gi18466639 Salmonella enterica; Sty R27 TrhG gi10957317 S. typhi ; S£ R100 TraG gi9507645 Shigella £exneri ; Eco F TraG gi9507812 E. coli; Sty pSLT TraU gi17233465 S. typhimurium; Sty pED208 TraG gi21632647 S. typhi; Vco SXT TraG gi21885271 V. cholerae ; Pre R391 TraG gi20095130 P. rettgeri; Rco RC0146 gi15892069 Rickettsia canorii ; Rpr RP108 gi15603985 Rickettsia prowazekii ; Eco R388 TrwI gi2661722 E. coli; Sen SO11 gi12719015 S. enterica; Eco R6K PilX6 gi12053572 E. coli ; Ype pYC orf5 gi10955839 Yersinia pestis; Sty R46 TraD gi17530595 S. typhimurium; Xfa pXF51 Xfa0011 gi10956722 X. fastidiosa; Mlo pMLa mlr9255 gi13488265 M. loti ; Mlo R71 msi411 gi20804241 M. loti; Ngo TraG gi14860859 N. gonorrhoeae; Pvu Rts1 orf242 gi21233904 P. vulgaris ; Bhe VirB6 gi6007533 Bartonella henselae ; Cac CAC2046 gi15895316 Clostridium acetobutylicum ; Nar pNL1 TraG gi10956931 N. aromaticivorans ; Eco R721 TraA gi10955522 E. coli; Ccr CC2420 gi16126659 Caulobacter crescentus; Bpe VirB6 gi420952 B. pertussis ; Hpy jhp0937 gi15612002 H. pylori; Sco SCD72A.15c gi21222528 Streptomyces coelicolor ; Ban pX01 pX01-79 gi10956326 Bacillus anthracis; Bf1 hydrophobic protein gi1813499 Bacillus ¢rmus; Cac CAC2403 gi15895669 C. acetobutylicum; Bth TraJ gi10444274 Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron; Nsp alr7534 gi17158670 Nostoc sp. PCC 7120. FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 10 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 PreR391TraB VcoSXTTraB SmeHtdB 100 StyR27TrhB PvuRts1TraB 100 StypED208TraB StyR100TraB EcoFTraB StypSLTTraB 98 100 100 RcoVirB10 100 EchVirB10 73 WolbachiaVirB10 64 NarpNL1TraB 89 88 MloR7ATrbI 89 Ccrcc2422 65 91 95 R64TraO 100 ReuTrbI RsoTrbI 65 58 MlopMLbmll9603 100 65 97 LpnIcmE/DotG XfapXF51Xfa40 LpnLvhB10 65 100 CtepTSATrbI EaeR751TrbI 100 73 CcrVirB10 RP4TrbI MlopMLamlr9259 98 AtupTiA6VirB10 RetVirB10 AtupOctopineVirB10 AtupTiC58VirB10 RrhpRi1724VirB10 BheVirB10 75 AtupATAGRpAT231 67 95 SmeVirB10 99 Retp42dVirB10 R388TrwE XcaVirB10 65 86 65 100 AtupOctopineTrbI 100 68 100 65 100 RrhpRi1724TrbI XaxpXAC64VirB10 RrhpNGR234aTrbI 65 PpupWWompfH 65 StyR46TraF 59 65 100 XaxVirB10 65 65 65 AacVirB10 85 65 BpeVirB10 HinaegyptiuspBF3031VirB10 100 88 HpyJ99orf1314 Hpyhp0527 EcoPilX10 Xfaxfa0014 BmeAbortusVirB10 EcoR721TraI 100 CjeComB3 HpyorfJ HpyComB3 50 changes been demonstrated [14,15]. The hexameric coupling protein is anchored in the inner membrane with the cytoplasY in mic domain forming a channel that measures 22 A diameter, which could easily accommodate a single strand Y ). The coupling protein is thought to use of DNA (V10 A ATP hydrolysis to energize the ‘pumping’ of DNA through the coupling protein channel [19,96]. Recently, the coupling protein of R27, TraGH , an FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 F-type system, has been shown to interact with the N-terminus of TrhBH , a member of the TraBF family. TrhBH was also shown to form multimers, possibly forming a ring structure that could extend the pore of the coupling protein into the periplasmic space [59]. TraBF of the F factor also interacts with TraKF , which in turn interacts with TraVF , a lipoprotein that could stabilize the secretin-like TraKF protein [49]. Secretins are known to form gated, outer membrane rings that allow the passage of macromolecules in response to a signal that opens the pore [97,98]. A TraKF secretin-like structure, anchored by TraVF , could, therefore, extend the conjugative pore from the coupling protein through to the outer membrane, via TraBF . Although there is evidence for such a structure in other secretion systems, this needs to be demonstrated experimentally for the T4SS. Consistent with the idea of TraBF , -KF and -VF forming the core of the pore which transfers DNA, expression of VirB3Ti , -B4Ti , -B7Ti , -B8Ti , -B9Ti and -B10Ti of the Ti plasmid in recipient cells increases the e⁄ciency of RSF1010 transfer [99]. This suggests that the presence of these proteins within recipients aids in the transport of the DNA into the cytoplasm. Since all of these VirB proteins, except VirB8Ti , have a homolog/analog in F-like T4SS, including the sca¡olding proteins of the putative pore (TraBF , -KF and -VF ; Table 1), it is likely that the pore extends from the donor inner membrane to the recipient cytoplasm. Consistent with this proposal, homologs of VirB7Ti and -B10Ti have been shown to be responsible for DNA uptake by H. pylori [5], illustrating that these proteins likely represent the minimal membrane-spanning pore for DNA transfer. Although these observations suggest a mechanism by which DNA could cross the donor envelope, the mechanism by which the DNA traverses the recipient envelope to gain access to the cytoplasm remains a key question. Some evidence is available that suggests the T4SS system 11 of F penetrates the recipient cell. TraGF has been implicated in entry exclusion involving protein^protein interactions between TraGF and TraSF , the entry exclusion protein, located in the donor and recipient cells, respectively [32]. This suggests that TraGF is translocated into the recipient cell and interacts with TraSF to block DNA transfer. Also, 35 S-labelled TraNF and possibly TraUF are found in the recipient cell after separation of the donor and recipient cells using magnetic bead technology (L.S. Frost, unpublished results). Since the net outcome of F-, P- and I-type conjugative systems is the same, there must be an underlying mechanism common to all T4SS, which do di¡er somewhat in their repertoire of proteins that promote pilus assembly and DNA transport. Does the F-pilus retract, and if it does, do the P- and I-type pili also retract ? Do P-type systems also translocate proteins into the recipient cell to form a stable mating junction? Does the DNA transfer through the pilus, situated within the conjugative pore, with the pilus penetrating the recipient cell envelope and depositing the DNA directly within the recipient cytoplasm, much like a phage tail tube within the contractile tails of T-even phages injects DNA? The idea that pili can be used to transport macromolecules is supported by the ¢ndings of Jin and He [100,101], who visualized protein secretion from the tips of type III secretion system pili. This observation implies that pili can indeed serve as a conduit for macromolecular tra⁄cking. 5. Relationships between T4SS, T3SS and T2SS Gram-negative bacteria possess multiple pathways for secreting macromolecules across the outer membrane [102], with conjugation via T4SS being one of the more complex pathways [8]. Secretion pathways with interesting similarities to T4SS are the type II secretion systems (T2SS; 12^16 proteins) and the type III secretion systems 6 Fig. 5. A phylogenetic tree illustrating the evolutionary relationship between TraBF , TrbIP and VirB10Ti . The tree was constructed as described in Fig. 3, and labeled using the same style of annotations. The following list comprises all of the relevant information in the homology tree in the following format: three-letter bacterial species abbreviation, plasmid name, gene name, accession number, full bacterial species name. Pvu RTS1 orf210 NP_640170 P. vulgaris ; Vco SXT TraB AAL59682 V. cholerae ; Pre R391 TraB AAM08009 P. rettgeri; Sme R478 HtdB AAD01913 S. marcescens; Sty R27 TrhB AAD54048 S. typhi; Sty pED208 TraB AAM90707 S. typhi; Sty R100 TraB BAA78855 S. typhimurium ; Eco F TraB AAC44179 E. coli ; Sty pSLT TraB AAL23486 S. typhimurium ; Nar pNL1 TraB NP_049165 N. aromaticivorans; Sty R64 TraO BAA78003 S. typhimurium ; Lpn IcmE CAA75165 L. pneumophila; Lpn LvhB10 CAB60060 L. pneumophila ; Ccr CC2422 NP_421225 C. crescentus ; Mlo pMLa mlr9259 NP_085799 M. loti; Ret pa VirB10 AAD55069 R. etli; Atu pTiA6 VirB10 AAF77170 A. tumefaciens ; Atu octopine-like Ti VirB10 NP_059808 A. tumefaciens; Atu pTiC58 VirB10 P17800 A. tumefaciens; Rrh pRi1724 riorf162 NP_066743 R. rhizogenes ; Bhe VirB10 AAF00948 B. henselae; Atu pAT AGR_pAT_231p NP_396101 A. tumefaciens ; Sme pSymA VirB10 NP_435956 S. meliloti ; Ret p42d VirB10 NP_659885 R. etli; Eco R388 TrwE CAA57031 E. coli; Xca VirB10 NP_637831 X. campestris ; Xax VirB10 NP_642932 X. axonopodis; Bpe VirB10 E47301 B. pertussis ; Hpy orf13/14 NP_223194 H. pylori strain J99; Hpy HP0527 AAD07594 H. pylori strain 26695; Hpy orfJ AAM03036 H. pylori strain PeCan18B ; Hpy ComB3 CAA10657 H. pylori strain P1; Cje pVir VirB10 AAF97747 Campylobacter jejuni; Eco R6K PilX10 CAC20148 E. coli; Bme VirB10 AAF73903 Brucella melitensis bv. abortus; Xfa pXF51 XFa0014 AAF85583 X. fastidiosa; Eco R721 TraI NP_065358 E. coli; Hin pBF3028 Bp120 NP_660236 Haemophilus in£uenzae biotype aegyptius; Aac pVT745 magB10 NP_067574 Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans; Sty R46 TraF NP_511197 S. typhimurium; Ppu pWWo MpfH NP_542921 P. putida; Xax pXAC64 VirB10 AAM39284 X. axonopodis; Rrh pNGR234a TrbI NP_443816 R. rhizogenes ; Rrh pRi1724 riorf120 NP_066701 R. rhizogenes ; Atu octopine-like Ti TrbI NP_059750 A. tumefaciens; Eco RP4 TrbI AAA26435 E. coli; Eae R751 TrbI AAC64450 E. aerogenes; Cte pTSA TrbI AAK38009 C. testosteroni; Xfa pXF51 XFa0040 AAF85609 X. fastidiosa; Mlo pMLb mll9603 NP_109459 M. loti; Rso TrbI NP_520696 R. solanacearum ; Reu Tn4371 TrbI CAA71794 Ralstonia eutropha; Ccr CC2685 AAK24651 C. crescentus; Mlo TrbI CAD31427 M. loti ; Wol VirB10 BAA97441 Wolbachia sp. strain wKueYO ; Ech VirB10 AAM00413 Ehrlichia cha¡eensis; Rco VirB10 AAL02927 R. canorii. FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 12 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 (T3SS; 20 proteins). T2SS are one of the terminal branches of the general secretory pathway, which is responsible for secreting a wide range of extracellular toxins and enzymes by Gram-negative bacteria [103]. T2SS are also closely related to secretion pathways for the biosynthesis of type IV pili [104]. Among the T3SS are molecular syringes that inject virulence e¡ector proteins directly into the cytoplasm of host cell [105]. T3SS also share both sequence and structural similarities with £agellar basal bodies [106,107]. Based on in silico analysis, the homology between T4SS, T3SS and T2SS is quite limited. However, each system does contain a secretin protein and an associated stabilizing lipoprotein, which together could function as a gated outer membrane channel that allows the passage of macromolecules. Each system also contains one or two NTPases that likely energize either assembly of the secretion apparatus or macromolecule secretion. NTPases contained within the T2SS (GspE) are homologous to the NTPases from P- and I-type T4SS (i.e. TrbBP /VirB11Ti and TraJI ), but not NTPases from F-like T4SS [26]. How energy is utilized in these systems will be key to understanding their di¡erences. Structural determination of key transfer proteins will undoubtedly provide valuable insight into the nature of T4SS that cannot be obtained from database searches. For example, the crystal structure of the coupling protein TrwB identi¢ed structural homologies to DNA ring helicases and therefore suggested a mechanism by which single-stranded DNA could be actively pumped through the conjugative pore. It will be interesting to determine if any homology exists between T4SS, T2SS and T3SS at the level of protein structure and whether the theme of interacting proteins assembled into multimeric rings is common to many secretion systems. From a mechanistic and anatomical standpoint, there are striking similarities between T4SS, T3SS and T2SS. Each secretion system is a multi-protein, membrane-associated complex that can assemble ¢lamentous appendages, such as pili or £agella, on the bacterial cell surface and are involved in macromolecular transport. Many type II and IV systems share the properties of retractile pili [12,76] and sensitivity to pilus-speci¢c bacteriophages [75], which presumably take advantage of pilus retraction for entry into the host. Some type III and IV systems share an ability to trigger macromolecular transport in response to contact with host eukaryotic cells [108] or bacterial cells [68], respectively. Although the molecular mechanisms for each of these processes are not yet fully understood, various aspects of these secretion pathways appear to be conserved, possibly re£ecting a common evolutionary origin of either complete systems or modular components of each system. Interesting parallels exist between the substrates secreted by T4SS and T2SS. For example, natural transformation, or DNA uptake, can be mediated by either T2SS [109] or T4SS [5]. Also, secretion of structurally similar toxins can occur by either a T2SS (cholera toxin) [103] or a T4SS (pertussis toxin) [91,92]. Another interesting comparison involves DNA transfer mediated by the F T4SS that shares mechanistic similarities to ¢lamentous phage (M13 and f1) replication and packaging, which uses a secretin/lipoprotein channel, thioredoxin and an NTPase [104]. Both systems use an evolutionarily related mechanism to produce a single-stranded DNA intermediate via rolling circle replication [110,111], which is either transferred to a recipient or packaged upon phage extrusion. The T4SS gene products assemble the conjugative pilus, a structure that is structurally related to class I ¢lamentous phages, which consists of a helical array of proteins around a circular, single-stranded DNA molecule [112], possibly providing insight into the transport of DNA during conjugation. The secretion system classi¢cation scheme (T2^T4SS) conveniently divides important pathways into logical categories, which has greatly facilitated the study and understanding of these systems [102]. However, the expanding genome databases and the molecular dissection of several model secretion systems has revealed both the diversity within and the shared relationships between secretion system categories. From an evolutionary perspective, these observations make it tempting to speculate that numerous variations of secretion pathways exist that are built on a ¢nite array of central modular components. 6. Future studies on T4SS Identi¢cation by genetic and computer-based methods of the essential components of T4SS provides a foundation to ask more detailed questions about the mechanism of macromolecular secretion, in general. Careful biochemical and genetic analysis of individual transfer proteins will continue to provide valuable insight into the mechanics of secretion. Methods to determine protein^protein interactions will be central to constructing a detailed model of the T4SS apparatus since microscopic analyses, so far, have proven uninformative. Such examples include the identi¢cation of the TraBF , -KF , -VF envelope-spanning structure [49] and identi¢cation of an interaction between TrhBH and the coupling protein TraGH [47] and the many examples in the VirBTi literature [2]. Identifying how macromolecules access the pore and initiate the transfer process as well as their e¡ect on the recipient as they enter the cytoplasm will also be key questions [10]. Bacterial conjugation provides a model system for studying bacterial signaling as the nature of the ever elusive mating signal remains unknown. It is anticipated that an external cue, possibly involving contact between donor and recipient, is transferred via the pilus, through the membrane-associated T4SS and coupling protein to the cytoplasmic relaxosome. This process appears to involve FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 pilus retraction, an as yet poorly understood phenomenon. Several T4SS components contain features of signaling molecules. For example, coiled-coil domains, such as those in TraBF and TraHF , which can undergo modi¢cation, have been implicated in molecular signaling [113] and modulation of binding through changes in the local cellular environment [114]. This signal could then trigger events that resemble phage infection and injection of DNA or the injection of proteins in a contact-mediated manner as seen in T3SS. [14] [15] [16] [17] Acknowledgements [18] The authors wish to thank Bart Hazes, Diane Taylor and members of her lab for unpublished data. We also wish to thank Sean Graham for his help in generating the phylogenetic tree data. [19] [20] [21] References [22] [1] Lederberg, J. and Tatum, E.L. (1946) Gene recombination in Escherichia coli. Nature 158, 558. [2] Christie, P.J. (2001) Type IV secretion : intercellular transfer of macromolecules by systems ancestrally related to conjugation machines. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 294^305. [3] Taylor, D.E., Gibreel, A., Lawley, T.D. and Tracz, D.M. (2003) Antibiotic resistance plasmids. In: Biology of Plasmids (Philips, G. and Funnel, B., Eds.), in press. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [4] Christie, P.J. and Vogel, J.P. (2000) Bacterial type IV secretion: conjugation systems adapted to deliver e¡ector molecules to host cells. Trends Microbiol. 8, 354^360. [5] Hofreuter, D., Odenbreit, S. and Haas, R. (2001) Natural transformation competence in Helicobacter pylori is mediated by the basic components of a type IV secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 41, 379^ 391. [6] Firth, N., Ippen-Ihler, K. and Skurray, R.A. (1996) Structure and function of the F-factor and mechanism of conjugation. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella : Cellular and Molecular Biology, Vol. 1 (Neidhardt, F.C., Ed.), pp. 2377^2401. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [7] Frost, L.S., Ippen-Ihler, K. and Skurray, R.A. (1994) Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor. Microbiol. Rev. 58, 162^210. [8] Lawley, T.D., Wilkins, B.M. and Frost, L.S. (2003) Bacterial conjugation in gram-negative bacteria. In: Biology of Plasmids (Phillips, G. and Funnel, B., Eds.), in press. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [9] Durrenberger, M.B., Villiger, W. and Bachi, T. (1991) Conjugational junctions : morphology of speci¢c contacts in conjugating Escherichia coli bacteria. J. Struct. Biol. 107, 146^156. [10] Lawley, T.D., Gordon, G.S., Wright, A. and Taylor, D.E. (2002) Bacterial conjugative transfer: visualization of successful mating pairs and plasmid establishment in live Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 44, 947^956. [11] Samuels, A.L., Lanka, E. and Davies, J.E. (2000) Conjugative junctions in RP4-mediated mating of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182, 2709^2715. [12] Novotny, C.P. and Fives-Taylor, P. (1974) Retraction of F pili. J. Bacteriol. 117, 1306^1311. [13] Clewell, D.B. and Helinski, D.R. (1969) Supercoiled circular DNAprotein complex in Escherichia coli : puri¢cation and induced conver- [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] 13 sion to an open circular DNA form. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 62, 1159^1166. Schroder, G., Krause, S., Zechner, E.L., Traxler, B., Yeo, H.J., Lurz, R., Waksman, G. and Lanka, E. (2002) TraG-like proteins of DNA transfer systems and of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system : inner membrane gate for exported substrates? J. Bacteriol. 184, 2767^2779. Szpirer, C.Y., Faelen, M. and Couturier, M. (2000) Interaction between the RP4 coupling protein TraG and the pBHR1 mobilization protein Mob. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 1283^1292. Ohki, M. and Tomizawa, J.I. (1968) Asymmetric transfer of DNA strands in bacterial conjugation. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 33, 651^658. Rupp, W.D. and Ihler, G. (1968) Strand selection during bacterial mating. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 33, 647^650. Zechner, E.L. et al. (2000) Conjugative-DNA transfer processes. In: The Horizontal Gene Pool (Thomas, C.M., Ed.), pp. 87^174. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam. Llosa, M., Gomis-Ruth, F.X., Coll, M. and de la Cruz, F. (2002) Bacterial conjugation : a two-step mechanism for DNA transport. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1^8. Henderson, D. and Meyer, R. (1999) The MobA-linked primase is the only replication protein of R1162 required for conjugal mobilization. J. Bacteriol. 181, 2973^2978. Rees, C.E. and Wilkins, B.M. (1990) Protein transfer into the recipient cell during bacterial conjugation : studies with F and RP4. Mol. Microbiol. 4, 1199^1205. Wilkins, B.M. and Thomas, A.T. (2000) DNA-independent transport of plasmid primase protein between bacteria by the I1 conjugation system. Mol. Microbiol. 38, 650^657. Herrera-Estrella, A., Van Montagau, M. and Wang, K. (1990) A bacterial peptide acting as a plant nuclear targeting signal: the amino-terminal portion of Agrobacterium VirD2 protein directs a betagalactosidase fusion protein into tobacco nuclei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 9534^9537. Howard, E.A., Zupan, J.R., Citovsky, V. and Zambryski, P.C. (1992) The VirD2 protein of A. tumefaciens contains a C-terminal bipartite nuclear localization signal implications for nuclear uptake of DNA in plant cells. Cell 68, 109^118. Ziemienowicz, A., Merkle, T., Schoumacher, F., Hohn, B. and Rossi, L. (2001) Import of Agrobacterium T-DNA into plant nuclei. Two distinct functions of VirD2 and VirE2 proteins. Plant Cell 13, 369^ 384. Planet, P.J., Kachlany, S.C., DeSalle, R. and Figurski, D.H. (2001) Phylogeny of genes for secretion NTPases: identi¢cation of the widespread tadA subfamily and development of a diagnostic key for gene classi¢cation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 2503^2508. Bradley, D.E., Taylor, D.E. and Cohen, D.R. (1980) Speci¢cation of surface mating systems among conjugative drug resistance plasmids in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 143, 1466^1470. Lanka, E. and Wilkins, B.M. (1995) DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 141^169. Komano, T., Yoshida, T., Narahara, K. and Furuya, N. (2000) The transfer region of IncI1 plasmid R64: similarities between R64 tra and Legionella icm/dot genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 1348^1359. Segal, G., Purcell, M. and Shuman, H.A. (1998) Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1669^1674. Vogel, J.P., Andrews, H.L., Wong, S.K. and Isberg, R.R. (1998) Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science 279, 873^876. Anthony, K.G., Klimke, W.A., Manchak, J. and Frost, L.S. (1999) Comparison of proteins involved in pilus synthesis and mating pair stabilization from the related plasmids F and R100-1: insights into the mechanism of conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 181, 5149^5159. Lawley, T.D., Gilmour, M.W., Gunton, J.E., Standeven, L.J. and FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 14 [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 Taylor, D.E. (2002) Functional and mutational analysis of conjugative transfer region 1 (Tra1) from the IncHI1 plasmid R27. J. Bacteriol. 184, 2173^2180. Lawley, T.D., Gilmour, M.W., Gunton, J.E., Tracz, D.M. and Taylor, D.E. (2003) Functional and mutational analysis of the conjugative transfer region 2 (Tra2) of the IncHI1 plasmid R27. J. Bacteriol. 185, 581^591. Majdalani, N., Moore, D., Maneewannakul, S. and Ippen-Ihler, K. (1996) Role of the propilin leader peptide in the maturation of F pilin. J. Bacteriol. 178, 3748^3754. Majdalani, N. and Ippen-Ihler, K. (1996) Membrane insertion of the F-pilin subunit is Sec independent but requires leader peptidase B and the proton motive force. J. Bacteriol. 178, 3742^3747. Harris, R.L., Sholl, K.A., Conrad, M.N., Dresser, M.E. and Silverman, P.M. (1999) Interaction between the F plasmid TraA (F-pilin) and TraQ proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 34, 780^791. Manchak, J., Anthony, K.G. and Frost, L.S. (2002) Mutational analysis of F-pilin reveals domains for pilus assembly, phage infection and DNA transfer. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 195^205. Lu, J., Manchak, J., Klimke, W., Davidson, C., Firth, N., Skurray, R. and Frost, L. (2002) Analysis and characterization of the IncFV plasmid pED208 transfer region. Plasmid 48, 24^37. Frost, L.S., Finlay, B.B., Opgenorth, A., Paranchych, W. and Lee, J.S. (1985) Characterization and sequence analysis of pilin from F-like plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 164, 1238^1247. Maneewannakul, K., Maneewannakul, S. and Ippen-Ihler, K. (1993) Synthesis of F pilin. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1384^1391. Eisenbrandt, R., Kalkum, M., Lai, E.M., Lurz, R., Kado, C.I. and Lanka, E. (1999) Conjugative pili of IncP plasmids, and the Ti plasmid T pilus are composed of cyclic subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22548^22555. Moore, D., Sowa, B.A. and Ippen-Ihler, K. (1981) Location of an F-pilin pool in the inner membrane. J. Bacteriol. 146, 251^259. Maher, D., Sherburne, R. and Taylor, D.E. (1993) H-pilus assembly kinetics determined by electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 175, 2175^ 2183. Shirasu, K. and Kado, C.I. (1993) Membrane location of the Ti plasmid VirB proteins involved in the biosynthesis of a pilin-like conjugative structure on Agrobacterium tumefaciens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 111, 287^294. Grahn, A.M., Haase, J., Bamford, D.H. and Lanka, E. (2000) Components of the RP4 conjugative transfer apparatus form an envelope structure bridging inner and outer membranes of donor cells: implications for related macromolecule transport systems. J. Bacteriol. 182, 1564^1574. Gilmour, M.W., Lawley, T.D., Rooker, M.M., Newnham, P.J. and Taylor, D.E. (2001) Cellular location and temperature-dependent assembly of IncHI1 plasmid R27-encoded TrhC-associated conjugative transfer protein complexes. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 705^715. Schmidt-Eisenlohr, H., Domke, N., Angerer, C., Wanner, G., Zambryski, P.C. and Baron, C. (1999) Vir proteins stabilize VirB5 and mediate its association with the T pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 181, 7485^7492. Harris, R.L., Hombs, V. and Silverman, P.M. (2001) Evidence that F-plasmid proteins TraV, TraK and TraB assemble into an envelopespanning structure in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 757^ 766. Deng, W.L. and Huang, H.C. (1999) Cellular locations of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae HrcC and HrcJ proteins, required for harpin secretion via the type III pathway. J. Bacteriol. 181, 2298^2301. Guilvout, I., Hardie, K.R., Sauvonnet, N. and Pugsley, A.P. (1999) Genetic dissection of the outer membrane secretin PulD: are there distinct domains for multimerization and secretion speci¢city? J. Bacteriol. 181, 7212^7220. Baron, C., O‘Callaghan, D. and Lanka, E. (2002) Bacterial secrets of secretion : EuroConference on the biology of type IV secretion processes. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1359^1365. [53] Schandel, K.A., Muller, M.M. and Webster, R.E. (1992) Localization of TraC, a protein involved in assembly of the F conjugative pilus. J. Bacteriol. 174, 3800^3806. [54] Cao, T.B. and Saier Jr., M.H. (2001) Conjugal type IV macromolecular transfer systems of Gram-negative bacteria : organismal distribution, structural constraints and evolutionary conclusions. Microbiology 147, 3201^3214. [55] Rabel, C., Grahn, A.M., Lurz, R. and Lanka, E. (2003) The VirB4 family of proposed tra⁄c nucleoside triphosphatases : common motifs in plasmid RP4 TrbE are essential for conjugation and phage adsorption. J. Bacteriol. 185, 1045^1058. [56] Schandel, K.A., Maneewannakul, S., Ippen-Ihler, K. and Webster, R.E. (1987) A traC mutant that retains sensitivity to f1 bacteriophage but lacks F pili. J. Bacteriol. 169, 3151^3159. [57] Firth, N. and Skurray, R. (1992) Characterization of the F plasmid bifunctional conjugation gene, traG. Mol. Gen. Genet. 232, 145^ 153. [58] Jones, C.J., Homma, M. and Macnab, R.M. (1989) L-, P-, and M-ring proteins of the £agellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium: gene sequences and deduced protein sequences. J. Bacteriol. 171, 3890^3900. [59] Gilmour, M.W., Gunton, J.E., Lawley, T.D. and Taylor, D.E. (2003) Interaction between the IncHI1 plasmid R27 coupling protein and a component of the R27 Type IV secretion system : TraG associates with the coiled-coil mating pair formation protein TrhB. Mol. Microbiol. (in press). [60] Bliska, J. (1996) How pathogens exploit interactions mediated by SH3 domains. J. Chem. Biol. 3, 7^11. [61] Klimke, W. (2002) PhD Thesis, Analysis of the mating pair stabilization system of the F-plasmid. Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB. [62] Collet, J.F. and Bardwell, J.C. (2002) Oxidative protein folding in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 44, 1^8. [63] Manwaring, N. (2001) PhD Thesis, Molecular analysis of the conjugative F-plasmid leading and transfer regions. School of Biological Sciences University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW. [64] Maneewannakul, S., Kathir, P. and Ippen-Ihler, K. (1992) Characterization of the F plasmid mating aggregation gene traN and of a new F transfer region locus trbE. J. Mol. Biol. 225, 299^311. [65] Harris, R.L. and Silverman, P.M. (2002) Roles of internal cysteines in the function, localization, and reactivity of the TraV outer membrane lipoprotein encoded by the F plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 184, 3126^ 3129. [66] Baron, C., Thorstenson, Y.R. and Zambryski, P. (1997) The lipoprotein VirB7 interacts with VirB9 in the membranes of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 179, 1211^1218. [67] Das, A., Anderson, L.B. and Xie, Y.H. (1997) Delineation of the interaction domains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB7 and VirB9 by use of the yeast two-hybrid assay. J. Bacteriol. 179, 3404^3409. [68] Kingsman, A. and Willetts, N. (1978) The requirements for conjugal DNA synthesis in the donor strain during Flac transfer. J. Mol. Biol. 122, 287^300. [69] Achtman, M., Kennedy, N. and Skurray, R. (1977) Cell-cell interactions in conjugating Escherichia coli: role of TraT protein in surface exclusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74, 5104^5108. [70] Klimke, W.A., Kennedy, R.A., Rypien, C.D., Harris, R.L., Silverman, P.M. and Frost, L.S. (2003) Analysis of the mating pair stabilization protein, TraN, of the F plasmid, reveals a dependence on disul¢de bond formation for stability and function. J. Bacteriol. (submitted). [71] Klimke, W.A. and Frost, L.S. (1998) Genetic analysis of the role of the transfer gene, traN, of the F and R100-1 plasmids in mating pair stabilization during conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 180, 4036^4043. [72] Moore, D., Maneewannakul, K., Maneewannakul, S., Wu, J.H., Ippen-Ihler, K. and Bradley, D.E. (1990) Characterization of the F-plasmid conjugative transfer gene traU. J. Bacteriol. 172, 4263^ 4270. FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03 T.D. Lawley et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 224 (2003) 1^15 [73] Bradley, D.E. (1980) Morphological and serological relationships of conjugative pili. Plasmid 4, 155^169. [74] Novotny, C.P. and Fives-Taylor, P. (1978) E¡ects of high temperature on Escherichia coli F pili. J. Bacteriol. 133, 459^464. [75] Paranchych, W. and Frost, L.S. (1988) The physiology and biochemistry of pili. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 29, 53^114. [76] Merz, A.J., So, M. and Sheetz, M.P. (2000) Pilus retraction powers bacterial twitching motility. Nature 407, 98^102. [77] Skerker, J.M. and Berg, H.C. (2001) Direct observation of extension and retraction of type IV pili. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6901^ 6904. [78] Sherburne, C.K., Lawley, T.D., Gilmour, M.W., Blattner, F.R., Burland, V., Grotbeck, E., Rose, D.J. and Taylor, D.E. (2000) The complete DNA sequence and analysis of R27, a large IncHI plasmid from Salmonella typhi that is temperature sensitive for transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 2177^2186. [79] Murata, T. et al. (2002) Complete nucleotide sequence of plasmid Rts1: implications for evolution of large plasmid genomes. J. Bacteriol. 184, 3194^3202. [80] Boltner, D., MacMahon, C., Pembroke, J.T., Strike, P. and Osborn, A.M. (2002) R391: a conjugative integrating mosaic comprised of phage, plasmid, and transposon elements. J. Bacteriol. 184, 5158^ 5169. [81] Beaber, J.W., Hochhut, B. and Waldor, M.K. (2002) Genomic and functional analyses of SXT, an integrating antibiotic resistance gene transfer element derived from Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 184, 4259^ 4269. [82] Romine, M.F. et al. (1999) Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J. Bacteriol. 181, 1585^1602. [83] Hamilton, H.L., Schwartz, K.J. and Dillard, J.P. (2001) Insertionduplication mutagenesis of Neisseria : use in characterization of DNA transfer genes in the gonococcal genetic island. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4718^4726. [84] Pansegrau, W. et al. (1994) Complete nucleotide sequence of Birmingham IncPK plasmids. Compilation and comparative analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 239, 623^663. [85] Thorsted, P.B. et al. (1998) Complete sequence of the IncPL plasmid R751: implications for evolution and organisation of the IncP backbone. J. Mol. Biol. 282, 969^990. [86] Winans, S.C. and Walker, G.C. (1985) Conjugal transfer system of the IncN plasmid pKM101. J. Bacteriol. 161, 402^410. [87] Zhu, J., Oger, P.M., Schrammeijer, B., Hooykaas, P.J., Farrand, S.K. and Winans, S.C. (2000) The bases of crown gall tumorigenesis. J. Bacteriol. 182, 3885^3895. [88] Backert, S., Ziska, E., Brinkmann, V., Zimny-Arndt, U., Fauconnier, A., Jungblut, P.R., Naumann, M. and Meyer, T.F. (2000) Translocation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in gastric epithelial cells by a type IV secretion apparatus. Cell. Microbiol. 2, 155^164. [89] Segal, E.D., Cha, J., Lo, J., Falkow, S. and Tompkins, L.S. (1999) Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14559^14564. [90] Stein, M., Rappuoli, R. and Covacci, A. (2000) Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA antigen after cag-driven host cell translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 1263^1268. [91] Covacci, A. and Rappuoli, R. (1993) Pertussis toxin export requires accessory genes located downstream from the pertussis toxin operon. Mol. Microbiol. 8, 429^434. [92] Weiss, A.A., Johnson, F.D. and Burns, D.L. (1993) Molecular characterization of an operon required for pertussis toxin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 2970^2974. [93] Guiney, D.G. (1993) Broad host range conjugative and mobilizable plasmids in gram-negative bacteriain: In: Bacterial Conjugation (Thomas, C.M., Ed.), pp. 75^104. Plenum Press, New York. 15 [94] Cabezon, E., Sastre, J.I. and de la Cruz, F. (1997) Genetic evidence of a coupling role for the TraG protein family in bacterial conjugation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 254, 400^406. [95] Hamilton, C.M. et al. (2000) TraG from RP4 and TraG and VirD4 from Ti plasmids confer relaxosome speci¢city to the conjugal transfer system of pTiC58. J. Bacteriol. 182, 1541^1548. [96] Panicker, M.M. and Minkley, E.G. (1985) DNA transfer occurs during a cell surface contact stage of F sex factor-mediated bacterial conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 162, 584^590. [97] Nouwen, N., Stahlberg, H., Pugsley, A.P. and Engel, A. (2000) Domain structure of secretin PulD revealed by limited proteolysis and electron microscopy. EMBO J. 19, 2229^2236. [98] Nouwen, N., Ranson, N., Saibil, H., Wolpensinger, B., Engel, A., Ghazi, A. and Pugsley, A.P. (1999) Secretin PulD: association with pilot PulS, structure, and ion-conducting channel formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8173^8177. [99] Bohne, J., Yim, A. and Binns, A.N. (1998) The Ti plasmid increases the e⁄ciency of Agrobacterium tumefaciens as a recipient in VirBmediated conjugal transfer of an IncQ plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7057^7062. [100] Jin, Q. and He, S.Y. (2001) Role of the Hrp pilus in type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae. Science 294, 2556^2558. [101] Jin, Q., Hu, W., Brown, I., McGhee, G., Hart, P., Jones, A.L. and He, S.Y. (2001) Visualization of secreted Hrp and Avr proteins along the Hrp pilus during type III secretion in Erwinia amylovora and Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 1129^1139. [102] Thanassi, D.G. and Hultgren, S.J. (2000) Multiple pathways allow protein secretion across the bacterial outer membrane. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 420^430. [103] Sandkvist, M. (2001) Biology of type II secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 271^283. [104] Russel, M. (1998) Macromolecular assembly and secretion across the bacterial cell envelope: type II protein secretion systems. J. Mol. Biol. 279, 485^499. [105] Buttner, D. and Bonas, U. (2002) Port of entry-the type III secretion translocon. Trends Microbiol. 10, 186^192. [106] Galan, J.E. and Collmer, A. (1999) Type III secretion machines : bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science 284, 1322^1328. [107] Kubori, T., Matsushima, Y., Nakamura, D., Uralil, J., Lara-Tejero, M., Sukhan, A., Galan, J.E. and Aizawa, S.I. (1998) Supramolecular structure of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Science 280, 602^605. [108] Galan, J.E. (2001) Salmonella interactions with host cells: type III secretion at work. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 53^86. [109] Dubnau, D. (1999) DNA uptake in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53, 217^244. [110] Asano, S., Higashitani, A. and Horiuchi, K. (1999) Filamentous phage replication initiator protein gpII forms a covalent complex with the 5P end of the nick it introduced. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 1882^1889. [111] Byrd, D.R. and Matson, S.W. (1997) Nicking by transesteri¢cation: the reaction catalysed by a relaxase. Mol. Microbiol. 25, 1011^1022. [112] Marvin, D.A., Hale, R.D., Nave, C. and Helmer-Citterich, M. (1994) Molecular models and structural comparisons of native and mutant class I ¢lamentous bacteriophages Ff (fd, f1, M13), If1 and IKe. J. Mol. Biol. 235, 260^286. [113] Surette, M.G. and Stock, J.B. (1996) Role of alpha-helical coiledcoil interactions in receptor dimerization, signaling, and adaptation during bacterial chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17966^17973. [114] Jelesarov, I., Durr, E., Thomas, R.M. and Bosshard, H.R. (1998) Salt e¡ects on hydrophobic interaction and charge screening in the folding of a negatively charged peptide to a coiled coil (leucine zipper). Biochemistry 37, 7539^7550. FEMSLE 11051 27-6-03