* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Class #10 - 5/14/12

J. Baird Callicott wikipedia , lookup

Thomas Nagel wikipedia , lookup

Paleoconservatism wikipedia , lookup

Internalism and externalism wikipedia , lookup

Virtue ethics wikipedia , lookup

Euthyphro dilemma wikipedia , lookup

Individualism wikipedia , lookup

Divine command theory wikipedia , lookup

Kantian ethics wikipedia , lookup

Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals wikipedia , lookup

The Moral Landscape wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg wikipedia , lookup

The Sovereignty of Good wikipedia , lookup

Bernard Williams wikipedia , lookup

Ethics in religion wikipedia , lookup

Ethics of artificial intelligence wikipedia , lookup

Alasdair MacIntyre wikipedia , lookup

Moral disengagement wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development wikipedia , lookup

Ethical intuitionism wikipedia , lookup

Moral development wikipedia , lookup

Consequentialism wikipedia , lookup

Morality throughout the Life Span wikipedia , lookup

Moral responsibility wikipedia , lookup

Utilitarianism wikipedia , lookup

Morality and religion wikipedia , lookup

Thomas Hill Green wikipedia , lookup

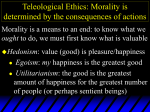

Philosophy 1010 Class #10 Chapter 7 Ethics Final Exam & Final Essays are due Next week Hints for Taking Final Exam Re-read chapter summaries – Chapters 1-5 & 7 Practice Quia Activities! Don’t just memorize the answers. Understand the questions & answers. Review textbook, powerpoints, your lecture notes as necessary to answer your questions. Come relaxed but prepared to finish the exam without a break! When taking the exam, read the question and all possible answers carefully before you decide which answer is best. It is often suggested that we all pretty much know what is right and wrong and the issue of ETHICS and MORALITY is finding the will and resolve to ACT or behave correctly when perhaps it is “easier” to do something else. Making Good Moral Judgments is Hard! We often will not agree on what is right. Contrary to what you may have thought, determining what is right will often be the primary issue. Is Morality more of an issue about character or conduct? That is, does one do the right thing because one has a virtuous character, or does one have a virtuous character because they consistently do the right thing? Or, saying this another way, in studying ethics should we focus on acts of conduct and determine what makes an act moral, or should we focus on virtue to determine what makes a person good, such that guarantees that her actions will be good. Principles of Ethics • According to the first approach specifically, Ethics investigates the problems and the questions that are posed about values as they relate to human conduct. • A value judgment is a choice between what is good or bad. What is a good movie is a value judgment, but not an ethical or moral judgment. It is an aesthetic judgment. • Thus, all moral judgments are value judgments, but there are many value judgments that are not moral judgments. Principles of Moral Reasoning • Please note that your view on whether God exists or not is not an ethical judgment, but a view you should allow God (assuming you believe in God) to direct your conduct is an ethical judgment. • If you assert that God exists, that is a belief that is either true or false, but not a value. If you believe that God exists and that you should “follow his commandments” (for example), then you have a belief and a value. You have made a judgment about what you should do in response to what you believe is true or false. • In an argument, a value judgment is a normative claim. A normative claim asserts what “ought to be” or “if something is good” as opposed to “what is” (a factual claim). Moral Issues & Subjectivity • When addressing moral issues, the claims we make and the premises we give often appear somewhat subjective. (Remember that if a claim is totally subjective, no argument for it (or against it) can be given.) • Always remember that to the extent the premises for a claim are subjective, they provide no support for your argument. • But morality is not generally a mere matter of subjective opinion and it is possible (although perhaps difficult) typically to put forward reasons to believe a moral claim. • Furthermore, moral issues and moral judgments are frequently too important to ignore or avoid. Approaches to Morality: Relativism & Subjectivism • Moral or ethical relativism is the view that what is right or wrong depends upon one’s group or culture. • This claim is different than the claim of cultural relativism that what is believed to be right or wrong depends upon one’s group or culture. Be on guard for someone arguing for the first claim but only supporting it with premises and evidence for the second claim. • For a moral relativist, however, is abortion right or wrong in the U.S. today? Presumably it depends if society thinks so, but what to say when society is fundamentally divided on the issue? • Moral subjectivism is the claim that all moral judgments are subjective, that if one thinks something is right or wrong then it is so for that person. Moral relativism suggests that: • There are multiple systems of morality, and with possible contradictions between them and without any means to resolve their differences from outside. • Thus, all moral systems should respect the values inherent in other systems • Moral values are relative to time and place. Argument For Moral Relativism: P1. Ethical beliefs and practices differ profoundly from one culture to another. P2. It is difficult to judge the ethical beliefs and practices of others (especially when they have good reasons for their moral claims). C. Therefore, the fundamental principles governing what acts are morally right or wrong vary from culture to culture. One Argument Against Moral Relativism P1. People once believed that the earth was flat and thus by relativism, we would have concluded that at that time, the world was flat. P2. The world is not flat and was not flat at any time. C. By analogy, morality and ethics are not dependent upon one’s culture. What might be good or right about Moral Relativism? 1. Although it might not be the only way to foster tolerance between cultures, it definitely does encourage tolerance and teaches us to have restraint from imposing our values on cultures that do not accept them. 2. It often helps us to reduce bigotry and force us to expand our own understanding beyond previously held, narrow points of view. 3. It seems to encourage psychological and sociological (i.e. scientific) explanations of behavior that we did not previously understand. 4. It seems to help each of us engage our fellow humans (who may be outside our “own group”) with more respect, admiration, and appreciation. 5. It recognizes that though we often think we make moral judgments that are universal, in fact the values that we relied on to make this argument was riddled with cultural biases and values. Now, what are some problems with moral or ethical relativism? If moral relativism is true, 1. We would appear to have no basis to judge another culture for anything they do, including slavery, the holocaust, genocide. 2. It would appear that whatever the majority of a culture wishes must be moral and any attempt to improve the culture (through civil rights, for example) is actually immoral. 3. It would appear that actions become moral or cease to be moral based on changing “polls.” 4. then it would appear that acts become moral or cease to be moral based on who you admit into your “culture.” Does the U.S. have one culture or many? Is culture a matter of ethnicity, religion, or ??? 5. then it would appear that even the idea of tolerance might not be a shared common value Other Approaches to Morality: Absolutism or Universalism • Though moral values are at times somewhat subjective or relativistic, not all moral values are. Many moral values can be addressed at least partially with objective principles and by fundamentals of critical thinking. • The opposite of the moral relativist is the moral absolutist who would argue that fundamentally only one and only one correct morality exists. What is right for Americans in the 20th century is what would have been right for all nations throughout history. • Although this view may seem too strong to argue on the basis of all moral judgments, it does seem somewhat reasonable in regard to certain fundamental moral judgments, e.g. slavery, pedophilia, etc. Note that Moral (or Ethical) Relativism and Universalism agree that: • There is right and wrong and we can have agreed upon standards of determining one from the other. • Thus, both of these views differ from other views which cannot provide any basis for common ground in developing ethical guidelines, such as subjectivism. Video: Does Morality Depend Upon One’s Culture? (#18) Approaches to Morality: Utilitarianism • Utilitarianism is the view that what is right or wrong depends upon the consequences of actions and decisions. • The view is associated with the philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. • According to this view, what is right is what will produce the greatest value (perhaps happiness) for the greatest number. • Intentions are irrelevant to whether or not an act is right! Utilitarianism • Utilitarians generally are arguing a normative claim. A utilitarian may accept the view that we often act from psychological egoism, but would say that when we do so, we may be acting unethically. • Note that Utilitarians are hard absolutists. • The principle of utility is sometimes referred to as the greatest happiness principle. • Utilitarianism is similar to but should be distinguished from the view held by Machiavelli that the means justifies the ends which may promote an Egoist objective. Utilitarianism does always advance the common good. Jeremy Bentham (1748 – 1832) • The classical view of utilitarianism was expressed by Jeremy Bentham. • When choosing a course of action, always pick the one that maximizes happiness and minimizes unhappiness for the maximum number of people • Bentham insisted that each individual must decide for themselves what provides pleasure and each person’s pleasure counts equally. Hedonistic Utilitarianism • Bentham is suggesting that what is good is that which is pleasurable and what is bad is what is painful. • Thus, his view is known as hedonistic utilitarianism. • However, this classic view of utility does understand that pursuing short-term pleasure may actually be a bad thing. But the reason is because exercising immediate and short-term pleasures may not be a rational approach for achieving maximum pleasure for all (or even for oneself) Problems with Classical Utilitarianism 1. The Problem of Sheer Numbers! If we are applying the greatest happiness principle, would it be moral then to abuse a few individuals for the enjoyment or welfare of the many? Human experiments? Animal experiments? Stem cell research? Snuff films? Dog fights? Human Torture? Abu Ghraib? 2. The Happiness Paradox We often found happiness only when we are searching for something else. The more we seem to value pleasure for itself, the more it seems to elude us. John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) The Utilitarianism approach of Bentham and the greatest happiness principle is deeply flawed. “Ask yourself whether you are happy and you cease to be so.” In response to Bentham, John Stuart Mill claims that happiness is an intellectual achievement, not merely pleasure. Mill argued that you cannot simply identify pleasure with good and evil with pain. Mill proposed a version of utilitarianism that did not fall back on hedonism. There are higher and lower pleasures. Intellectual values drive us to the higher pleasures. John Stuart Mill A Revision of Utilitarianism • Bentham’s view does not adequately inform us as to what pleasure and pain is. • The greatest pleasures are “acquired tastes” and derive from achievement -- the joy of solving a mathematical problem, of writing an opera, of playing a violin, etc. • “It is better to be a human dissatisfied than a pig satisfied, better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.” John Stuart Mill’s Higher & Lower Pleasures • Humans will prefer pleasures that maintain some form of dignity. Maximizing pleasure for the common good depends on social equality, but such cannot be achieved without proper education • Thus, Mill emphasized the necessary role of education for all. Social equality is achieved by providing opportunity for all to achieve the highest pleasures, not everybody settling for the lower pleasures. • Mill’s Harm Principle states that no mentally competent adult should be forced to be subject to other’s tastes, even if they are not in the majority, as long as they do no harm to others. John Stuart Mill’s Harm Principle • This view may appear contradictory with his earlier view of general education, but it is not. • What Mill is saying is that we should educate all to give them the opportunity to achieve, but ultimately if they choose not to have the values that their education encouraged them to have, no compulsion should be advanced to make them live by any values other than the ones they choose for themselves. • Thus, Mill would likely argue on the matter of “same sex marriage” that we (even if we are the majority) should “mind our own business!” • But what about the teenage girl who wishes to commit suicide because she is pregnant? Should we “mind our own business” on this, or should we intervene on the basis the she is committing harm to others? Act vs. Rule Utilitarianism • Utilitarians after John Stuart Mill have clarified Mill’s position by differentiating Act Utilitarianism from Rule Utilitarianism. • Act Utilitarianism says that one should always do whatever act will create the greatest happiness for the greater number of people. • Act Utilitarianism seems to suggest that it would be right to abuse individuals for the the common good. • Rule Utilitarianism says that one should always do whatever type of act or follow the rule that will create the greatest happiness for the greater number of people. Thus, rule utilitarianism suggests that a pattern or rule of abusing individuals for the sake of the common good is not right. Video: Do Consequences Make Actions Right? (#19) Although it appears correct to many of us, utilitarianism has many critics. Two major issues are: 1. Utilitarianism seems not to account for the importance of duties and obligations and intentions. Consider the case of a man who attempts to shoot his friend out of rage and jealousy and misses and hits instead a sniper who is about to shoot a rifle into a crowded mall. Did this man act morally? If only consequences matter, we would probably have to say that he did. 2. What are consequences anyway? They only happen after we take action. They are hypothetical. Thus, an action cannot be said to be moral or not until the consequences are known. Remember, intentions don’t count. But how long do we have to wait? With many moral choices, all the consequences are not ever known. Thus, can we ever say if the act is good or not? Morality as Doing the Right Thing • Many argue against utilitarianism that what makes an action moral is the intention under which it is done. A moral act is done because it is the right thing to do. • But what is the right thing to do? Such a view can be interpreted many ways and may even appear to beg the question. • Is the right thing to do to follow the “golden rule which is stated quite explicitly by many early Greek philosophers & in the New Testament -- Matthew 7:12: "So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets." This principle exists in all the major religions: Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Jainism, Confucianism, and Taoism. Problems Even With the Golden Rule • But how does one know how others want to be treated? You may not be able to ask them because they do not have the relevant experience. • "Do not do unto others as you would expect they should do unto you. Their tastes may not be the same." …George Bernard Shaw Morality as Doing the Right Thing • Immanuel Kant proposes this sort of moral theory which emphasizes the nature of duty and obligation • Thus, Kant’s view is called Deontology. • In Kant’s view, what makes an act the right thing to do is not just because it is done with a good intention. • It is the right thing to do if it is is done out of an intention to follow a moral law or rule out of a sense of duty or obligation. • Otherwise the act is only done only as a hypothetical imperative. • A hypothetical imperative is a act which is done based on a conditional want or desire, e.g. If you want to get an ‘A’ in this class, you should study for the final exam. Kant’s Deontology • For Immanuel Kant, an act is truly moral only if it is done out of the categorical imperative which does not depend on circumstances or conditional wants or desires. The act is done for the sake of the principle of doing the right thing. • Actions done fulfilling the categorical imperative are truly acts of good will and thus, the person who does so has a good will. • To determine if our acts are good, we must verify that our own intentions ought to applied as a general law for everybody. Kant’s Deontology • For Immanuel Kant, another way of stating the categorical imperative is that we should treat all persons as ends in themselves, never as means to an end. Treat someone as they agree to be treated. • This second formulation of the Categorical Imperative is essentially the same principle as the first because the categorical imperative universalizes your maxim. Both formulations are basically saying do not treat yourself as an exception! • Both formulations capture the essence of seems to be the wisdom of the golden rule! Video: Can Rules Define Morality? (#20) Other Approaches to Morality • A popular view of morality of course is the view that moral duty is set by a divine being. • But does anyone here remember Socrates? • But is an act right simply because God has commanded it, or does God command it because it is right? • In the first view, is God’s commandments arbitrary? That doesn’t seem right. In the second view, is there a criteria for morality which we can study independent of God’s approval of certain acts? Thus, many suggest that the Divine Commandment view “begs the question.” Rather than focusing on ethics as a matter of what to do, another view focuses on how to be. In this view, known as virtue ethics, a moral issue is not one of single actions but is a matter of good character. It is a way of living. In this view, ethics arises out of the nature of a good person. This approach is what was largely accepted by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Plato & Socrates: What is the Nature of a Virtuous Character? What then makes an Act Moral or Good? What is the Good Life? How Should We Live? What Makes Life Worth Living, that is, Good? Aristotle: What is a Virtuous Person? • Aristotle suggests to be virtuous is to act with excellence, that is to live your life well according to its purpose • Each person has both an individual purpose (what you do best?) and a human purpose. • Man’s universal, human purpose is to reason, to think rationally. In so doing, he will develop a rational character which is moral goodness. • There are two forms of virtue: 1) When our soul controls our desires, we engage our moral virtues. 2) When our soul contemplates intellectual or spiritual matters, we engage our intellectual virtues. (“sophia”) Aristotle: What is a Virtuous Person? • Virtue thus responds to each situation at the right time, in the right way, in the right amount, for the right reason. • Thus, a virtuous person will act with “moderation.” • This view is called “The Golden Mean” (and should be carefully distinguished from “the golden rule.”) • Aristotle would cite the example of an artistic masterpiece from which nothing can be added or subtracted without harming the work’s “excellence.” • Only by following such a life of moderation will a person achieve important virtues such as happiness or courage.