* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Current and future climate of the Cook Islands

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Climate sensitivity wikipedia , lookup

2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference wikipedia , lookup

German Climate Action Plan 2050 wikipedia , lookup

Global warming hiatus wikipedia , lookup

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Attribution of recent climate change wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Climate change feedback wikipedia , lookup

Economics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

General circulation model wikipedia , lookup

Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme wikipedia , lookup

Physical impacts of climate change wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Years of Living Dangerously wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Canada wikipedia , lookup

Instrumental temperature record wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Climate change, industry and society wikipedia , lookup

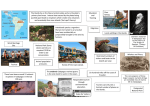

Penrhyn Pukapuka Nassau Suwarrow No rth e Sout rn Co hern Palmerston ok Co Is ok nd s Rakahanga Manihiki la Is Aitutaki la nd s Manuae Mitiaro Takutea Atiu Mauke South Pacific Ocean Avarua Rarotonga Mangaia Current and future climate of the Cook Islands > Cook Islands Meteorological Service > Australian Bureau of Meteorology > Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Current climate of the Cook Islands Jul Oct 35 400 300 200 30 100 0 Temperature (ºC) 25 20 15 300 200 100 0 Apr Sea surface temperature Rarotonga, Cook Islands,159.80ºW, 21.20ºS Monthly rainfall (mm) 30 25 15 20 Temperature (ºC) Penrhyn, Cook Islands,158.05ºW, 9.03ºS Jan Minimum temperature Average temperature 35 Maximum temperature Jan Apr Jul Figure 1: Seasonal rainfall and temperature at Penrhyn (in the north) and Rarotonga (in the south). 2 400 from November to May. This is when the South Pacific Convergence Zone is most active and furthest south. From November to March the South Pacific Convergence Zone is wide and strong enough for the Northern Group to also receive significant rainfall. The driest months of the year in the Cook Islands are from June to October. Rainfall in the Cook Islands is strongly affected by the South Pacific Convergence Zone. This band of heavy rainfall is caused by air rising over warm waters where winds converge, resulting in thunderstorm activity. It extends across the South Pacific Ocean from the Solomon Islands to east of the Cook Islands (Figure 2). It is centred close to or over the Southern Group The Cook Islands’ climate varies considerably from year to year due to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. This is a natural climate pattern that occurs across the tropical Pacific Ocean and affects weather around the world. There are two extreme phases of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation: El Niño and La Niña. There is also a neutral phase. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation has opposite effects on the Northern and Southern Groups. In Rarotonga, El Niño events tend to bring drier and cooler conditions than normal, while in the north El Niño usually brings wetter conditions. Ocean temperatures warm in the north during an El Niño event so air temperatures also warm. Oct Monthly rainfall (mm) Seasonal temperatures differ between the northern and southern Cook Islands. The Northern Cook Islands’ (Northern Group) position so close to the equator results in fairly constant temperatures throughout the year, while in the Southern Cook Islands (Southern Group) temperatures cool off during the dry season (May to October, Figure 1). Changes in temperatures are strongly tied to changes in the surrounding ocean temperature. The annual average temperature at Penrhyn in the Northern Group is 28°C and at Rarotonga in the Southern Group is 24.5°C. Federated States of Micronesia I n t e r t r o p i c a l 20oN Z o n e C o n v e r g e n c e Kiribati Vanuatu Tuvalu Pa cif ic Fiji Northern Co Cook Islands nve Samoa rge nc e Niue Tonga 500 Southern Cook Islands Zo ne 1,000 2,000 160oW 0 170oW 180o 170oE 160oE 150oE 140oE 130oE 120oE H 110oE 10oS So ut h Solomon Islands Papua New Guinea M o n East Timor s o o n 0o Tr a d e W i n d s 1,500 20oS l Kilometres 30oS poo Nauru 140oW Wa r m Marshall Islands 150oW Palau 10oN H No. of tropical cyclones Figure 2: The average positions of the major climate features in November to April. The arrows show near surface winds, the blue shading represents the bands of rainfall convergence zones, the dashed oval shows the West Pacific Warm Pool and H represents typical positions of moving high pressure systems. 7 6 Tropical cyclones 11-yr moving average 5 4 3 2 1 19 69 19 /70 71 19 /72 73 19 /74 75 19 /76 77 19 /78 79 19 /80 81 19 /82 83 19 /84 85 19 /86 87 19 /88 89 19 /90 91 19 /92 93 19 /94 95 19 /96 97 19 /98 99 20 /00 01 20 /02 03 20 /04 05 20 /06 07 20 /08 09 /1 0 0 Figure 3: Number of tropical cyclones passing within 400 km of Rarotonga. The 11-year moving average is in purple. Tropical cyclones Tropical cyclones affect the Cook Islands between November and April. In the 41-year period between 1969 and 2010, 47 tropical cyclones passed within 400 km of Rarotonga, an average of just over one cyclone per season (Figure 3). The number of cyclones varies widely from year to year, with none in some seasons but up to six in others. Over the period 1969 to 2010, cyclones occurred more frequently in El Niño years. 3 Changing climate of the Cook Islands Penrhyn’s annual rainfall has increased Annual maximum and minimum temperatures have increased in both Rarotonga (Figure 4) and Penrhyn since 1950. In Rarotonga, maximum temperatures have increased at a rate of 0.04°C per decade. These temperature increases are part of the global pattern of warming. Data since 1950 show a clear increasing trend in annual rainfall at Penrhyn (Figure 5), but no trend in seasonal rainfall. There are no clear trends in annual or seasonal rainfall at Rarotonga. Over this period, there has been substantial variation in rainfall from year to year at both sites. Average Temperature (ºC) 25.5 El Niño La Niña 25 24.5 24 23.5 23 2005 2000 1995 1990 1985 1980 1975 1970 1965 1960 1955 1950 22.5 Year 5000 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 As ocean water warms it expands causing the sea level to rise. The melting of glaciers and ice sheets also contributes to sea-level rise. Instruments mounted on satellites and tide gauges are used to measure sea level. Satellite data indicate the sea level has risen near the Cook Islands by about 4 mm per year since 1993. This is slightly larger than the global average of 2.8 – 3.6 mm per year. This higher rate of rise may be partly related to natural fluctuations that take place year to year or decade to decade caused by phenomena such as the El NiñoSouthern Oscillation. This variation in sea level can be seen in Figure 7 which includes the tide gauge record since 1977 and the satellite data since 1993. Ocean acidification has been increasing About one quarter of the carbon dioxide emitted from human activities each year is absorbed by the oceans. As the extra carbon dioxide reacts with sea water it causes the ocean to become slightly more acidic. This impacts the growth of corals and organisms that construct their skeletons from carbonate minerals. These species are critical to the balance of tropical reef ecosystems. Data show that since the 18th century the level of ocean acidification has been slowly increasing in the Cook Islands’ waters. 2005 2000 1995 1990 1985 1980 1975 1970 1965 1960 1955 El Niño La Niña 1950 Rainfall (mm) Figure 4: Annual average temperature for Rarotonga in the Southern Group. Light blue bars indicate El Niño years, dark blue bars indicate La Niña years and the grey bars indicate neutral years. Sea level has risen National Environment Service, Government of the Cook Islands Temperatures have increased Year Figure 5: Annual rainfall for Penrhyn in the Northern Group. Light blue bars indicate El Niño years, dark blue bars indicate La Niña years and the grey bars indicate neutral years. Islet and coral microatolls in Penrhyn. 4 Future climate of the Cook Islands Climate impacts almost all aspects of life in the Cook Islands. Understanding the possible future climate of the Cook Islands is important so people and the government can plan for changes. How do scientists develop climate projections? There are many different global climate models and they all represent the climate slightly differently. Scientists from the Pacific Climate Change Science Program (PCCSP) have evaluated 24 models from around the world and found that 18 best represent the climate of the western tropical Pacific region. These 18 models have been used to develop climate projections for the Cook Islands. The climate projections for the Cook Islands are based on three IPCC emissions scenarios: low (B1), medium (A1B) and high (A2), for time periods around 2030, 2055 and 2090 (Figure 6). Since individual models give different results, the projections are presented as a range of values. 2090 800 2055 2030 1990 700 600 500 400 300 Figure 6: Carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations (parts per million, ppm) associated with three IPCC emissions scenarios: low emissions (B1 – blue), medium emissions (A1B – green) and high emissions (A2 – purple). The PCCSP has analysed climate model results for periods centred on 1990, 2030, 2055 and 2090 (shaded). National Environment Service, Government of the Cook Islands The future climate will be determined by a combination of natural and human factors. As we do not know what the future holds, we need to consider a range of possible future conditions, or scenarios, in climate models. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) developed a series of plausible scenarios based on a set of assumptions about future population changes, economic development and technological advances. For example, the A1B (or medium) emissions scenario envisages global population peaking mid-century and declining thereafter, very rapid economic growth, and rapid introduction of new and more efficient technologies. Greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions scenarios are used in climate modelling to provide projections that represent a range of possible futures. CO2 Concentration (ppm) Global climate models are the best tools for understanding future climate change. Climate models are mathematical representations of the climate system that require very powerful computers. They are based on the laws of physics and include information about the atmosphere, ocean, land and ice. Damage caused by Tropical Cyclone Pat, February 2010. Mangaia Beach, Southern Cook Islands. 5 Future climate of the Cook Islands This is a summary of climate projections for Cook Islands. For further information refer to Volume 2 of Climate Change in the Pacific: Scientific Assessment and New Research, and the web-based climate projections tool – Pacific Climate Futures (available at www.pacificclimatefutures.net). Temperatures will continue to increase Changing rainfall patterns Projections for all emissions scenarios indicate that the annual average air temperature and sea surface temperature will increase in the future in the Cook Islands (Table 1). By 2030, under a high emissions scenario, this increase in temperature is projected to be in the range of 0.5 – 0.9°C in the Northern Group and 0.4 –1.0ºC in the Southern Group. There is uncertainty around rainfall projections for the Cook Islands as model results are not consistent. However, average annual and seasonal rainfall is generally projected to increase over the course of the 21st century. For the Southern Group average rainfall during the wet season is expected to increase due to the projected intensification of the South Pacific Convergence Zone. Droughts are projected to become less frequent throughout this century. More very hot days Increases in average temperatures will also result in a rise in the number of hot days and warm nights, and a decline in cooler weather. More extreme rainfall days Less frequent but more intense tropical cyclones On a global scale, the projections indicate there is likely to be a decrease in the number of tropical cyclones by the end of the 21st century. But there is likely to be an increase in the average maximum wind speed of cyclones by between 2% and 11% and an increase in rainfall intensity of about 20% within 100 km of the cyclone centre. In the Cook Islands region, projections tend to show a decrease in the frequency of tropical cyclones by the late 21st century and an increase in the proportion of the more intense storms. Model projections show extreme rainfall days are likely to occur more often. Table 1: Projected annual average air temperature changes for the Cook Islands for three emissions scenarios and three time periods. Values represent 90% of the range of the models and changes are relative to the average of the period 1980-1999. 2030 (°C) 2055 (°C) 2090 (°C) Low emissions scenario 0.2–1.0 0.7–1.5 0.9 –2.1 Medium emissions scenario 0.4 –1.2 0.9 –1.9 1.4–3.0 High emissions scenario 0.5 – 0.9 1.0 –1.8 2.0–3.2 Low emissions scenario 0.2–1.0 0.5–1.5 0.7–1.9 Medium emissions scenario 0.3 –1.1 0.7–1.9 1.2–2.8 High emissions scenario 0.4 –1.0 0.9 –1.7 1.8–3.2 Geoff Mackley Northern Cook Islands Southern Cook Islands 6 Rarotonga, Cyclone Meena, 2005. Sea level is expected to continue to rise in the Cook Islands (Table 2 and Figure 7). By 2030, under a high emissions scenario, this rise in sea level is projected to be in the range of 4-15 cm. The sea-level rise combined with natural year-to-year changes will increase the impact of storm surges and coastal flooding. As there is still much to learn, particularly how large ice sheets such as Antarctica and Greenland contribute to sea-level rise, scientists warn larger rises than currently predicted could be possible. Figure 7: Observed and projected relative sea-level change near the Cook Islands. The observed sea-level records are indicated in dark blue (relative tide-gauge observations) and light blue (the satellite record since 1993). Reconstructed estimates of sea level near the Cook Islands (since 1950) are shown in purple. The projections for the A1B (medium) emissions scenario (representing 90% of the range of models) are shown by the shaded green region from 1990 to 2100. The dashed lines are an estimate of 90% of the range of natural yearto-year variability in sea level. Table 2: Sea-level rise projections for the Cook Islands for three emissions scenarios and three time periods. Values represent 90% of the range of the models and changes are relative to the average of the period 1980-1999. 2030 (cm) Low emissions scenario 5–15 10 –26 17– 45 Medium emissions scenario 5 –15 10 – 30 19 –56 High emissions scenario 4–15 10 –29 19–58 2055 (cm) 2090 (cm) Ocean acidification will continue Under all three emissions scenarios (low, medium and high) the acidity level of sea waters in the Cook Islands region will continue to increase over the 21st century, with the greatest change under the high emissions scenario. The impact of increased acidification on the health of reef ecosystems is likely to be compounded by other stressors including coral bleaching, storm damage and fishing pressure. 90 80 70 60 Sea level relative to 1990 (cm) Sea level will continue to rise Reconstruction Satellite altimeter Tide gauges (3) Projections 50 40 30 20 10 0 −10 −20 −30 1950 2000 Year 2050 2100 7 Changes in the Cook Islands’ climate > Temperatures have warmed and will continue to warm with more very hot days in the future. > Annual rainfall since 1950 > By the end of this has increased at Penrhyn in the Northern Cook Islands but there are no clear trends in rainfall at Rarotonga in the Southern Cook Islands. Rainfall patterns are projected to change over this century with more extreme rainfall days and less frequent droughts. > Sea level near century projections suggest decreasing numbers of tropical cyclones but a possible shift towards more intense categories. the Cook Islands has risen and will continue to rise throughout this century. > Ocean acidification has been increasing in the Cook Islands’ waters. It will continue to increase and threaten coral reef ecosystems. The content of this brochure is the result of a collaborative effort between the Cook Islands Meteorological Service and the Pacific Climate Change Science Program – a component of the Australian Government’s International Climate Change Adaptation Initiative. This information and research conducted by the Pacific Climate Change Science Program builds on the findings of the 2007 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report. For more detailed information on the climate of the Cook Islands and the Pacific see: Climate Change in the Pacific: Scientific Assessment and New Research. Volume 1: Regional Overview. Volume 2: Country Reports. Available from November 2011. Contact the Cook Islands Meteorological Service: web: www.cookislands.pacificweather.org email: [email protected] phone: +682 20603 or +682 25920 www.pacificclimatechangescience.org ©P acific Climate Change Science Program partners 2011.