* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Kant and the force of duty - The Richmond Philosophy Pages

Internalism and externalism wikipedia , lookup

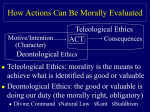

Antinomianism wikipedia , lookup

Utilitarianism wikipedia , lookup

Jurisprudence wikipedia , lookup

Bernard Williams wikipedia , lookup

Ethics in religion wikipedia , lookup

John McDowell wikipedia , lookup

School of Salamanca wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg wikipedia , lookup

Morality and religion wikipedia , lookup

Consequentialism wikipedia , lookup

Ethics of artificial intelligence wikipedia , lookup

Alasdair MacIntyre wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development wikipedia , lookup

Moral disengagement wikipedia , lookup

Ethical intuitionism wikipedia , lookup

Moral development wikipedia , lookup

Morality throughout the Life Span wikipedia , lookup

Moral relativism wikipedia , lookup

Kantian ethics wikipedia , lookup

Secular morality wikipedia , lookup

Kant and the force of duty It is impossible to conceive of anything at all in the world, or even out of it, which can be taken as good without qualification, except a good will (I 1). 1. Context Kant and critical philosophy. The deflation of rationalist metaphysics and knowledge claims of ultimate reality. Hume and an awakening from dogmatic slumbers. Dissatisfaction with claims of empiricism. Knowledge, the human perspective and the role of concepts. Causation and freedom Analytic/synthetic; a priori/ a posteriori. The synthetic a priori. Noumenal and phenomenal Pietism 2. Ethics The need for ‘pure ethics’. The certainty of our status as free agents. The Enlightenment goal of overcoming one’s own immaturity (our immaturity); finding the source of authority within reason. Fundamental principle or basis that allows us to answer the question: what ought I to do? Kant approaches moral philosophy by reflecting upon its nature, upon its possibility. His approach connects with two intuitive questions about what makes an action morally acceptable. What if everyone did that? Can you just use him like that? An answer to the question must be one that is an answer to whoever asks it. That is, an answer must be absolutely general or universal in scope. Nothing can be a moral principle which can not be a principle for all. Moral principles cannot be grounded in our contingent desires, inclinations or needs. 3. Ethics and reason Ethics to be grounded in reason and the principles of ethics to be constructed through rational procedures. Inclination v. duty. Hypothetical v. categorical imperatives. The key point is not one of grammar, but of motivation. The categorical nature of morality. The necessity of moral demands and the contingency of the demands of inclination and desire. The moral law, command and our experience of it as duty. The perfect (holy) will as infinite and wholly rational obeys the moral law spontaneously. We are finite and have empirical concerns and inclinations. 1 Action of distinctively moral worth is motivated by a sense of duty. Intention and motivation count not consequences. The moral law is synthetic a priori. It is a principle of reason known by a faculty akin to intuition. 4. The categorical imperative and universalisation Maxims - principle under which one acts Universalisation as a test for moral permissibility. Formulations CI - Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law (II 52). CI is the most general way in which the categorical imperative can be expressed. Reason alone discloses to us the basis of morality, the form of the moral law commanding and directing our intentions and actions. Kant proceeds to give more specified formulations of the categorical imperative to show how it can be developed in parallel ways, ways which indicate how are to understand the concept and apply it in practice. The key formulations are: Formula of the law of nature Act as if the maxim of your action were to become through your will a universal law of nature (II 52) Law of nature? The idea is that a law of nature specifies an absolute regularity. Such maxims would apply to everyone and everyone would always follow them. The formulation of CI in terms of laws of nature also captures the thought that the maxims or principles when universalised need to be consistent with the empirical facts of the natural world in which actions are undertaken. Formula of the end in itself Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end (II 66-67). Formula of the kingdom of ends Act as if you were through your maxims a legislating member of the kingdom of ends (II 74) This captures the idea that one act on principles all can share through their rationality and on principles which respect the capacities and dignity of each person. In so far as we are rational each us would will just the same universal 2 laws. The image of the Kingdom of Ends invites us to think of each person as at once a legislator and bound by the very law enacted, law which respects the like status of all. In this sense the Kantian rational self is literally autonomous self-legislating. 5. Illustrations The case of false promising - the problem of contradiction in conception and contradiction in will. The case of suicide. Respect for persons (perhaps most influential formulation of CI). Individuals as rational beings with their own projects and ends. Persons as the source of value of goods and practices. Persons as such possess dignity. The failure to respect the humanity of the other is a failure to act in a way that leaves in place the capacity of another to act, to pursue her ends. It is a violation of their status as an agent, a failure to recognise them as properly a person. To be autonomous, to pursue my ends it must be possible for me to dissent from or consent to what others do with respect to me. Reason therefore tells us that an individual cannot be treated as an end if he is subjected to coercion or deception. N.B not rule out treating others as means in some respects (e.g. the train driver I made use of this morning), but that we ought never to treat others merely as means. Intentions and actions. The ‘second best’ case of acting as if one were acting in accordance with morally worthy maxims. 6. Perfect and imperfect duties The possibility of completely discharging a duty. Self-development as an imperfect duty Assisting others as a rational response to our vulnerability and mutual dependence. To treat finite creatures like myself as ends requires not just that I adopt maxims which respect their capacity to act as freely determining agents, but that I support their limited and fragile capacity to act. However, what limits are there to the possible assistance required by others? How could I have a perfect duty, one that can be discharged completely? In a world with a plurality of agents our capacity to help others or develop ourselves is necessarily limited, indeterminate and selective. Obligations correspondingly imperfect. Towards a theory in which principles of virtue play an important role developed in Metaphysics of Morals Part II. 3 7. Freedom, God and immortality Tension between natural world of causal determinism (which we experience directly through e.g. our desires and inclinations) and our experience qua agents of freedom in decisions. Humans as parts of the natural, phenomenal world and parts of the noumenal world. Metaphysical incoherence? Two words or two ways of viewing our nature? Freedom must be postulated. We know we are free from moral experience and it is a condition of the possibility of that experience. Also tension between the moral goodness at which free agents aim and the happiness natural creatures pursue. Indeed, it might seem that often happiness is readily secured by those who fail to aim at moral goodness. Co-ordination of moral goodness and happiness is the highest good and it is possible provided we postulate a benevolent God and immortality. Kant accepts that three postulates cannot be theoretically known to be true, but they are necessary postulates of practice. N.B. changes in later writings. 8. Some challenges Empty formalism and abstraction. Cannot detach an account of morality from our conceptions of the good. Kant places the right before the good, but now there is no content in an understanding of morality. No appreciation of the embeddedness of moral relations in context. Can we separate what we ought to do from how we are, from those values and practices in which our lives gain value, purpose and cohesion? Conflicts between duties - what do I tell the murderer seeking you? Insufficient role for inclinations, attitudes and emotions. It is morally repugnant to act from duty alone. It is impossible to lead a worthwhile life gripped by duty. Also, what about the consequences? We do seem to accord a place for outcomes in our moral judgements. The die-hard racist, P, who consistently universalises the principle of extermination. Even if P were in their position P would still will that they, including P, should be killed. If that is so, then universalisation not a sufficient criterion of moral permissibility. But universalisation is a necessary condition. Now a question arises of whether there are moral principles which one would be irrational to regard as a universalisable maxim. See Hooker pp.19-20. Does the identification of non-universalisable maxims require the presupposition of substantive principles? False promising is incoherent, but do we already need to accept that we ought to endorse the practice of promising? 4