* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

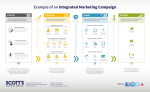

Download An Outline for an Integrated Marketing Communications Campaign

Target audience wikipedia , lookup

Social media marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing research wikipedia , lookup

Internal communications wikipedia , lookup

Marketing strategy wikipedia , lookup

Marketing plan wikipedia , lookup

Guerrilla marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Youth marketing wikipedia , lookup

Multicultural marketing wikipedia , lookup

Digital marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing mix modeling wikipedia , lookup

Direct marketing wikipedia , lookup

Green marketing wikipedia , lookup

Street marketing wikipedia , lookup

Global marketing wikipedia , lookup

Sensory branding wikipedia , lookup

Advertising campaign wikipedia , lookup