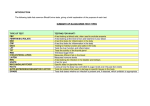

* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chronic Inflammation

Atherosclerosis wikipedia , lookup

Immune system wikipedia , lookup

Molecular mimicry wikipedia , lookup

Lymphopoiesis wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatic fever wikipedia , lookup

Adaptive immune system wikipedia , lookup

Periodontal disease wikipedia , lookup

Polyclonal B cell response wikipedia , lookup

Cancer immunotherapy wikipedia , lookup

Ankylosing spondylitis wikipedia , lookup

Adoptive cell transfer wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Sjögren syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatoid arthritis wikipedia , lookup

Psychoneuroimmunology wikipedia , lookup

Immunosuppressive drug wikipedia , lookup

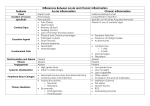

PATHOLOGY Chronic Inflammation Chronic inflammation may occur: • either as a sequel to acute inflammation (acute inflammationchronic inflammation), or • as a primary immune response to a foreign antigen (usually viral). Inflammation A dynamic contunium of change Resolution (no scar) Organization (exudatescar *) Inciting Stimulus Acute Inflammation Abscess Chronic-active Inflammation Chronic Inflammation Resolution with scarring* *The longer the stimulus persists, the greater the scarring will be. Chronic inflammation is considered to be inflammation of prolonged duration (weeks or months) in which active inflammation, tissue destruction, and attempts at healing are proceeding simultaneously. It may follow acute inflammation, as described earlier, chronic inflammation frequently begins insidiously, as a low-grade, flaming, often asymptomatic response. Etiology of Chronic Inflammation Persistent infections by certain microorganisms Mycobacterium Treponema pallidum certain fungi. Prolonged exposure to potentially toxic agents, either exogenous or endogenous (silicosis) Autoimmune diseases Chronic inflammation is characterized by: (1) infiltration with mononuclear cells, which include macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, a reflection of a persistent reaction to injury, (2) tissue destruction, largely induced by the inflammatory cells, (3) attempts at repair by connective tissue replacement, namely proliferation of fibroblasts, in particular, fibrosis. FIBROSIS There are four components to this process: 1. Formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) 2. Migration and proliferation of fibroblasts 3. Deposition of extracellular matrix 4. Maturation and organization of the fibrous tissue Fibrosis after chronic bronchitis. Scarring after chronic inflammation-Lung Inflammation Chronic Inflammation – Syphilis Lymphocytic chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the wall of the aorta in syphilitic aortitis. Inflammation Chronic Inflammation Histologic features cells – macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells Tissue destruction by ongoing inflammation, Mononuclear thought to be due to cytokines produced locally by the mononuclear cells Attempts fibrosis. at healing, including fibroblasts and Inflammation Chronic Inflammation Monocyte/Macrophages They are components of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), previously known as the reticuloendothelial system (RES). • Key cell in chronic and granulomatous inflammation • Reproduce locally, at the site of injury • Produce numerous cytokines, which continue to recruit additional cells, including more macrophages • May present antigen to T-cells, producing specific hypersensitivity reactions The MPS consists of closely related cells of bone marrow origin, including blood monocytes, and tissue macrophages. The latter are diffusely scattered in the connective tissue or clustered in organs such as the liver (Kupffer’s cells), spleen and lymph nodes (sinus histiocytes), and lungs (alveolar macrophages). Blood monocytes begin to emigrate early in acute inflammation, and within 48 hours predominant cell type. Extravasation of monocytes is governed by the same factors involved in neutrophil emigration, namely adhesion molecules and chemical mediators with chemotactic and activating properties. When the monocyte reaches the extravascular tissue it undergoes transformation into a larger phagocytic cell, the macrophage. In addition to performing phagocytosis, macrophages have the potential of being “activated,” a process that results in an increase in cell size, increased levels of lysosomal enzymes, more active metabolism, and greater ability to phagocytose and kill ingested microbes. Activation signals include cytokines (e.g., IFN-g) secreted by sensitized T lymphocytes, bacterial endotoxins, other chemical mediators, and ECM proteins like fibronectin. Following activation, the macrophages secrete a wide variety of biologically active products that are important mediators of the tissue destruction, vascular proliferation, and fibrosis characteristic of chronic inflammation In chronic inflammation macrophage accumulation persists, mediated by different mechanisms, each predominating in different types of reactions: 1. Continued recruitment of monocytes from the circulation, which results from the steady expression of adhesion molecules and chemotactic factors. (most important source for macrophages) Chemotactic stimuli for monocytes C5a; cytokines of the IL-8 family (chemokines) produced by activated macrophages and lymphocytes (MCP-1 for monocytes); certain growth factors (PDGF and TGF-b); fragments from the break-down of collagen, fibronectin and fibrinopeptides. 2. Local proliferation of macrophages after their emigration from the bloodstream. 3. Immobilization of macrophages within the site of inflammation. Indeed, certain cytokines (macrophage inhibitory factor) and oxidized lipids can cause such immobilization Lymphocytes: Lymphocytes are mobilized in both antibody- and cell-mediated immune reactions and also, for reasons unknown, in non-immune mediated inflammation. Lymphocytes of different types (T, B) or states (naive, activated or memory T cell) use various adhesion molecules (VLA-4/VCAM-1 and ICAM-1/ LFA-1 predominantly) and chemical mediators (largely cytokines) to migrate into inflammatory sites. Lymphocytes can be activated by contact with antigen. Activated lymphocytes produce cytokines (formerly called as: “lymphokines”), and one of these, IFN-g is a major stimulator of monocytes and macrophages. Plasma cells: They produce antibody directed either against persistent antigen in the inflammatory site or against altered tissue components. Eosinophils: They are characteristic of immune reactions mediated by IgE and of parasitic infections. Like neutrophils, they use adhesion molecules and chemotactic agents (derived from mast cells, lymphocytes, or macrophages) to exit the blood. Eosinophils are phagocytic and undergo activation. Their granules contain major basic protein (MBP), a highly cationic protein that is toxic to parasites but also causes lysis of mammalian epithelial cells. They may thus be of benefit in parasitic infections but contribute to tissue damage in immune reactions. Plasma cells Types of Chronic Inflammation 1. Non-granulomatous Chronic Inflammation a) Chronic viral infections b) Chronic autoimmune diseases c) Chronic chemical intoxications d) Chronic nonviral infections e) Allergic inflammation and metazoal infections, 2. Granulomatous Chronic Inflammation Non-granulomatous Chronic Inflammation Characterized by the accumulation of sensitized lymphocytes (specifically activated by antigen), plasma cells, and macrophages in the injured area. These cells are scattered diffusely throughout the tissue, however, and do not form granulomas. Scattered tissue necrosis and fibrosis are common. Classification of non-granulomatous chronic inflammation: a) Chronic viral infections b) Chronic autoimmune diseases c) Chronic chemical intoxications d) Chronic nonviral infections e) Allergic inflammation and metazoal infections a) Chronic viral infections: Persistent infection of parenchymal cells by viruses main components are a B cell response and a T cell cytotoxic response. The affected tissue shows accumulation of lymphocytes and plasma cells that produce cytotoxic effects on the cell containing the viral antigen, causing cell necrosis. This cytotoxic effect is mediated either by killer T lymphocytes or by cytotoxic antibody acting with complement. Ongoing parenchymal cell necrosis is associated with repair characterized by fibroblast proliferation and deposition of collagen. b) Chronic autoimmune diseases: immune response mediated by cytotoxic antibody and killer T cells occurs in several autoimmune diseases. The antigen involved is a host cell molecule that is perceived as foreign by the immune system. The pathologic result is similar to the nongranulomatous chronic inflammation seen in chronic viral infections, with cell necrosis, fibrosis, and lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration of the tissue. c) Chronic chemical intoxications: Persistent toxic substances such as alcohol produce chronic inflammation, notably in the pancreas and liver. The toxic substance is not antigenic, but by causing cell necrosis it may result in alteration of host molecules so that they become antigenic and evoke an immune response. The features of cell necrosis and repair by fibrosis in such cases dominate the features of the immune response. In many cases of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis, the lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration is slight. d) Chronic nonviral infections: specific type of non-granulomatous chronic inflammation is seen with certain microorganisms; (i) survive and multiply in the cytoplasm of macrophages after direct phagocytosis (ii) evoke a very ineffective T cell response. accumulation of large numbers of foamy macrophages in the tissue. The macrophages are present diffusely in the tissue without aggregating into granulomas. The ability of the macrophage to kill the organism is limited because of the poor T cell response, permitting the organisms to multiply in the cell. large numbers of organisms are present in the cytoplasm of the macrophages. The main defense appears to be direct phagocytosis by the macrophages. Variable numbers of plasma cells and lymphocytes may be present. Accumulation of infected macrophages in the tissue causes nodular thickening of the affected tissue, a clinical feature that is typical of this type of chronic inflammation. e) Allergic inflammation and metazoal infections: Eosinophils are present in acute hypersensitivity reactions and accumulate in large numbers in tissues subject to chronic or repeated allergic reactions. Eosinophils may have evolved as a defense against infection with various metazoal parasites. Eosinophils respond chemotactically to complement C5a and factors released by mast cells and in turn release a variety of enzymes and basic proteins. Eosinophils bear high-affinity Fc receptors for IgA and low-affinity receptors for IgE. Eosinophils are derived from a bone marrow precursor in common with mast cells and basophils, play a role in modulating histamine release or histamine catabolism. Mast cells and basophils have high-affinity Fc receptors for IgE. Chronic Granulomatous Inflammation This is a distinctive pattern of chronic inflammatory reaction in which the predominant cell type is an activated macrophage with a modified epithelial-like appearance (epithelioid cells) . Granuloma: aggregation of macrophages that are transformed into epitheloid cells surrounded by a collar of mononuclear leukocytes, principally lymphocytes and occasionally plasma cells . The cells in a granuloma are: macrophages and/or histiocytes (principal), lymphocytes (principal), fibroblasts, giant cells. • • • A cellular mechanism for dealing with indigestible substances The principal cells involved in granulomatous inflammation are macrophages and lymphocytes Epithelioid histiocytes are the hallmark of granulomatous inflammation A granuloma is an abnormal structure built from at least two activated macrophages adhering to one another. Such macrophages are called epithelioid cells. Epithelioid cells have abundant pink cytoplasm, indistinct borders, elongated, euchromatin-rich, reticulated nuclei. There are two types of granulomas: Foreign body granulomas incited by relatively inert foreign bodies. Immune granulomas Two factors determine the formation of immune granulomas: The presence of indigestible particles of organisms (e.g., the tubercle bacillus) T cell-mediated immunity to the inciting agent. Granulomas with suppuration With pus in their centers, stellate microabscesses. Bacterial diseases with a propensity to involve lymph nodes: lymphogranuloma cat venereum, scratch fever, brucellosis, plague, tularemia, glanders-melioidosis, listeria, camphylobacter, yersinia infection. Granulomas with caseation necrosis Typical of certain fungal and mycobacterial infections: histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, tuberculosis, leprosy, atypical mycobacteria. Granulomas can contain syncytial giant cells (polykaryons): Langhans giant cells (in the necrotizing granulomas: tuberculosis) nuclei Foreign body giant cells (in the non-necrotizing granulomas: foreign body granuloma) with arranged in a horseshoe around the edge nuclei dispersed more or less evenly Asteroid bodies (in the non-necrotizing granulomas: foreign body granuloma, sarcoidosis) altered cytoskeletal components in the shapes of stars Schaumann bodies (in the non-necrotizing granulomas: sarcoidosis) laminated calcified nuggets; "conchoid bodies“. Granulomatous Inflammation • • • Immunity may be judged by its effect on the invading organism, but an adverse effect on the host is generally termed hypersensitivity. Destruction of tissue is primarily via the action of killer T cells (CD8+), directed by macrophages. Products of activated T lymphocytes are important in transforming macrophages into epitheloid cells and multinucleated giant cells. Granulomatous diseases*** Mycobacterial infections: tuberculosis leprosy Fungal diseases Sarcoidosis Lymphogranuloma inguinale Foreign body granuloma Chronic granulomatous disease Crohn’s disease Leishmaniasis cutis Berylliosis Brucellosis Syphilis Inflammation Granulomatous Inflammation Fibroblasts Lymphocytes Macrophages, Epithelioid Cells, and Giant Cells Caseous Necrosis Caseating Granuloma Non-caseating Granuloma Langhans giant cells Asteroid bodies Schaumann bodies Inflammation Granulomatous Inflammation Tuberculous lung, showing massive destruction by granulomatous inflammation. This type of response is simply the best the body can do, since the inciting organism cannot be removed. Mycobacteria may live for years, perhaps even a lifetime, within granulomas. FUNCTION & RESULT OF CHRONIC INFLAMMATION Chronic inflammation serves to contain and remove an injurious agent that is not easily eradicated by the body. Containment and destruction of the agent are largely dependent on immunologic reactivity, whether these are achieved by (1) direct killing by activated lymphocytes, (2) interaction with antibodies produced by plasma cells, or (3) activation of macrophages by lymphokines produced by T lymphocytes. Persistent tissue destruction, with damage to both parenchymal cells and stromal framework, is a hallmark of chronic inflammation. As a consequence, repair cannot be accomplished solely by regeneration of parenchymal cells, even in organs whose cells are able to regenerate. Attempts at repairing tissue damage then occur by replacement of non-regenerated parenchymal cells by connective tissue, which in time produces fibrosis and scarring. The process is granulation tissue and is fundamentally similar to that occurring in the healing of wounds, but because the injury is persistent, and the inflammatory reaction ebbs and flows, the events are less predictable. Granulation Tissue Formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) Migration and proliferation of fibroblasts Deposition of extracellular matrix Maturation and organization of the fibrous tissue, also known as remodeling. Granulation Tissue The process of repair begins early in inflammation. Sometimes as early as 24 hours after injury, fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells being proliferating to form (by 3 to 5 days) the specialized type of tissue (granulation tissue) that is the hallmark of healing. The term granulation tissue derives from its pink, soft, granular appearance on the surface of wounds, but it is the histologic features that are characteristic: The proliferation of new small blood vessels New vessels originate by budding or sprouting of pre-existing vessels, a process called angiogenesis or neovascularization. The proliferation of fibroblasts. Several factors can induce angiogenesis, notably basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF or vascular permeability factor [VPF ]). Migration of fibroblasts to the site of injury and their subsequent proliferation are undoubtedly triggered by growth factors, such as PDGF, EGF, FGF, and TGF-b, and the fibrogenic cytokines, derived in part from inflammatory macrophages. Some of these growth factors also stimulate synthesis of collagen and other connective tissue molecules. These new vessels have leaky interendothelial junctions, allowing the passage of proteins and red cells into the extravascular space. Thus, new granulation tissue is often edematous. Characteristics of acute and chronic inflammation ACUTE CHRONIC Vascular changes Vasodilation and Increased permeability Minimal Cellular infiltrates Polymorphs Mononuclear Stromal changes Minimal separation due to edema Cellular proliferation Fibrosis Inflammation Acute vs. Chronic Inflammation Acute inflammation Accumulation of fluid and plasma components in the affected tissue Intravascular stimulation of platelets Presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) Chronic inflammation Lymphocytes, macrophages plasma cells, and MIXED ACUTE & CHRONIC INFLAMMATION Because acute and chronic inflammation represent different types of host response to injury, features of both types of inflammation may coexist in certain circumstances, as in chronic suppurative inflammation and recurring acute inflammation. Chronic Suppurative Inflammation The surrounding viable tissue responds with a longstanding inflammatory process in which areas of suppuration (liquefied necrotic tissue and neutrophils) alternate with areas of chronic inflammation (lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages) and fibrosis. Such a pattern occurs in chronic suppurative osteomyelitis and pyelonephritis. If the area of suppuration localizes to an abscess that remains over a long period, a fibrous wall of increasing thickness forms. The difference between an acute and a chronic abscess lies in the thickness of the fibrous wall; both forms are filled with pus. "chronic abscess" with elements of both acute and chronic inflammation. Seen here in the right middle lung lobe is just such a chronic abscess. Recurrent Acute Inflammation Repeated attacks of acute inflammation may occur if there is a predisposing cause, eg, in the gallbladder when there are gallstones. Each attack of acute inflammation is followed by incomplete resolution that leads to a progressively increasing number of chronic inflammatory cells and fibrosis. Depending on the time of examination, the picture may be mainly that of chronic inflammation or of acute superimposed on chronic inflammation. The terms subacute inflammation and acute-on-chronic inflammation are also used to denote this pattern. mixed inflammation is typical of repeated or recurrent inflammation a diagnosis of "acute and chronic cholecystitis" or "acute and chronic cervicitis" can be made. Morphologic Patterns The severity of the reaction, its specific cause, and the particular tissue and site involved all introduce morphologic variations in the basic patterns of acute and chronic inflammation: 1. Serous inflammation Fibrinous inflammation Suppurative or Purulent inflammation Necrotizing inflammation Hemorragic inflammation 2. 3. 4. 5. 1. Serous Inflammation Serous inflammation is marked by the outpouring of a thin fluid that, depending on the size of injury, is derived from either the blood serum or the secretions of mesothelial cells lining the peritoneal, pleural, and pericardial cavities (called effusion). The skin blister resulting from a burn or viral infection represents a large accumulation of serous fluid, either within or immediately beneath the epidermis of the skin. Types of Serous Inflammation Vesicle (blister): an elevation (<1 cm) of the epidermis containing watery liquid (herpes labialis). Bulla (large blister): an elevation (>1 cm) of the epidermis containing watery liquid (bullous pemphigoid, sunburn). Catarrh: inflammation of a mucous membrane (especially affecting the nose and air passages- rhinitis catarrhalis) 2. Fibrinous Inflammation With more severe injuries and the resulting greater vascular permeability, larger molecules such as fibrin pass the vascular barrier. A fibrinous exudate develops when the vascular leaks are large enough or there is a procoagulant stimulus in the interstitium (e.g., cancer cells). A fibrinous exudate is characteristic of inflammation in body cavities, such as the pericardium and pleura. Histologically, fibrin appears as an eosinophilic meshwork of threads, or sometimes as an amorphous coagulum. Fibrinous exudates may be removed by fibrinolysis, and other debris by macrophages (resolution). But when the fibrin is not removed it may stimulate the ingrowth of fibroblasts and blood vessels and thus lead to scarring. Conversion of the fibrinous exudate to scar tissue (organization) within the pericardial sac will lead either to opaque fibrous thickening of the pericardium and epicardium in the area of exudation or, more often, to the development of fibrous strands that bridge the pericardial space. 3. Suppurative or Purulent Inflammation This form of inflammation is characterized by the production of large amounts of pus or purulent exudate consisting of neutrophils, necrotic cells, and edema fluid. Certain organisms (e.g., staphylococci) produce this localized suppuration and are therefore referred to as pyogenic (pusproducing) bacteria. Abscess: focal localized collections of purulent inflammatory tissue caused by suppuration buried in a tissue, an organ, or a confined space (fruncle, dental abscess) Phlegmon: a purulent inflammation and infiltration of connective tissue without collection (acute appendicitis) Pustule: a small circumscribed elevation of the skin containing pus and having an inflamed base (subcorneal pustular dermatosis) Empyema: the presence of pus in a body cavity (as the pleural cavity; called also pyothorax). Abscesses are produced by deep seeding of pyogenic bacteria into a tissue. An abscess has a central region that appears as a mass of necrotic white cells and tissue cells. There is usually a zone of preserved neutrophils about this necrotic focus, and outside this region vascular dilatation and parenchymal and fibroblastic proliferation occur, indicating the beginning of repair (pyogenic membrane). In time, the abscess may become walled off by connective tissue that limits further spread. 4. Necrotizing inflammation An ulcer is a local defect, or excavation, of the surface of an organ or tissue that is produced by the sloughing (shedding) of inflammatory necrotic tissue. Ulceration can occur only when an inflammatory necrotic area exists on or near the surface. It is most commonly encountered in (1) inflammatory necrosis of the mucosa of the mouth, stomach, intestines, or genitourinary tract, and (2) subcutaneous inflammations of the lower extremities in older persons and diabetics who have circulatory disturbances that predispose to extensive necrosis. Ulcerations are best exemplified by the peptic ulcer of the stomach or duodenum. During the acute stage, there is intense polymorphonuclear infiltration and vascular dilatation in the margins of the defect. With chronicity, the margins and base of the ulcer develop fibroblastic proliferation, scarring, and the accumulation of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells. A Cavern is a hollow defect within a solid organ, which is produced by the sloughing of inflammatory necrotic tissue. It is most commonly encountered in Cavitaty tuberculosis due to the Caseous necrosis. Pus is either an exudate or an area of liquefaction necrosis containing neutrophilic leukocytes and necrotic debris. The preferred adjective to describe things with lots of pus is purulent. To produce pus is to suppurate. Pus which literally fills an important body cavity is called an empyema. Color of pus: Pus always has a yellow-green tinge because of myeloperoxidase. Classic yellow pus (as in a staphylococcal boil) also includes some lipid from necrotic tissue. Pseudomonas bacteria make a dye which imparts a blue-green fluorescence to pus. Inflammation Systemic Manifestations of Inflammation • Fever - clinical hallmark of inflammation • • • • Endogenous pyrogens: IL-1 and TNF-a Leukocytosis - may be neutrophils, eosinophils, or lymphocytes Leukopenia - rare Acute Phase Reactants - non-specific elevation of many serum proteins - will markedly increase the “red-cells sedimentation rate (ESR)” Leukocytosis and Leukopenia Mediators increased production and early release of neutrophils from the bone marrow Increased neutrophils in the blood stream Leukocytosis, the presence of young neutrophils is called a left shift. Bone marrow inhibition Leukopenia viral infections, unusual bacterial infections (typhoid, rickettsial disease). Inflammation Systemic Manifestations of Inflammation • Shock – most common in Gram-negative septicemia (bacteria in the bloodstream), although it can occur with Gram-positive bacteremia • • Lipopolysaccharide (LPS or endotoxin) of Gram-negatives can produce symptoms of shock when injected into animals TNF-a can produce a similar syndrome. Complications and sequelae Acute inflammation Serous inflammation Catarrh (asphyxia, diarrhea) Perifocal edema (brain) Suppurative/purulent inflammation Pyemia/septicemia Fistulization Empyema Pressure (brain) Ulcer Perforation (stomach, bowel) Bleeding (stomach, bowel) Stenosis (stomach, bowel). Chronic inflammation Scar and Keloid Stenosis (heart valves, GI, urinary, ect.) Failure (heart valves) Obstruction (urinary, GI, biliary, respiratory, ect.) Adhesion (periton, pleura) Amyloidosis (kidney, liver, adrenal, spleen).