* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download sample paper with annotations

Slavery in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Military of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Executive magistrates of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Demography of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Augustus wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

First secessio plebis wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republican governors of Gaul wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Senatus consultum ultimum wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

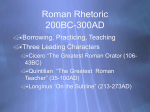

Jane Smith Mrs. Eckstein World Studies 8 April 2011 A Roman Senator and His Society While most people are aware of the accomplishments of ancient Rome, many are unaware of the underside to its class-based society, filled with dirty politics and slavery. Imperium, by Robert Harris, is set toward the end of the Roman Republic, a time of change and upheaval. Its focus is on Cicero, a rising orator, lawyer, and politician, and his slave and personal secretary, Tiro. Overall, the novel stays as close to the historical record as possible in its depiction of Roman social classes, Roman slavery, and the intricacies of the Roman political system. In Imperium, Cicero is a member of the Senate and campaigns for several political offices, including praetor and consul; the book ends when he won the election for consul. As in the novel, in real life, after holding lower-level offices, Cicero became a praetor at the age of forty, and a consul at forty-three (Shelton 215). Consul was the highest office that could be held during the Roman Republic. They were the administrators of public affairs and supreme commanders of the army; they only served for one year, but for that year they had almost kinglike power (214-215). Political campaigns in late Republican Rome were nearly endless, because elections were held each year. Politicians had to devote their lives to polishing their images, excelling as a lawyer, attracting supporters, and even marrying for political convenience (219). In Imperium, Cicero is described as having married his wife for money, because in order to be in the Senate a person had to have a minimum amount of money and property. In the book Cicero also campaigned ceaselessly, and had callers at his door every morning. Every case he took in the book helped his political career in some way. At one point he prosecuted a corrupt governor in order to make a name for himself; later, he defended a different corrupt governor in order to establish his patriotism to Rome. During late Republican Rome, the Senate and other high political offices were dominated by the aristocracy, which held great wealth and power. Cicero came from an aristocratic family (Clayton), but was still considered a “new man” because none of his ancestors had served as consul (Shelton 220). Interestingly, the Senate lacked formal authority, but its advice was always followed (Clayton). This meant that it was indeed a powerful political body in Rome, as depicted in Imperium. Throughout the book, Cicero is depicted as having difficulty as to whether to side with the aristocracy or the poor, or the “masses.” He had several arguments with his wife, who wanted him to become a firm ally of the aristocracy. Social class and slavery were clear themes in the book. According to Richard Hooker, the Second Punic War increased wealth inequality in Rome, because many small farmers lost their farms and land when Hannibal raised the countryside. The poor flooded the cities, while the rich bought up the land and maintained large estates. The war also led to an influx of slaves, and by the time Cicero was born, the majority of the population of Italy was composed of slaves (Hooker). The novel is narrated by Cicero’s personal slave Tiro, who was treated well as a personal secretary and the inventor of the shorthand system of writing. Most slaves in Rome worked in much harsher conditions, particularly in the countryside, where they would often work in shackled gangs from morning to night (Holland 143). Whippings and torture were not rare (143). A gladiatorial uprising led by Spartacus was the result (144-146). This was depicted in the book when Cicero and Tiro saw the prisoners of Crassus crucified along the Appian Way. Most in Rome, including slaves themselves, did not question the system of slavery, only their position in it (143-144). While in the book Tiro had discomfort at the sight of the crucifixions, he mostly did not question his place as a slave, having grown up in a society where it is assumed as a part of life. Roman social class, slavery, and Roman politics (including the Senate and political campaigns) were depicted accurately and thoroughly in Imperium. This book gives the reader an accurate sense of at least these aspects of Roman history. In the back of the book the author, Robert Harris, acknowledged that he did his best to stay accurate to the history, and when he had to invent events, they were events that could have happened, based on the conditions of the time. Some have faulted the book for trying to be too contemporary, and drawing parallels between the pirates of the time and the modern war on terror (Theroux). This, however, constituted a small part of the novel; the rest appears to be without any major flaws. Works Cited Clayton, Edward. "Cicero (106-43 BCE)." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. N.p., 14 July 2005. Web. 6 Mar. 2011. <http://www.iep.utm.edu/cicero/>. Holland, Tom. Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. New York: Anchor, 2005. Hooker, Richard. "Rome: The Crisis of the Republic." World Civilizations. Washington State University, 6 June 1999. Web. 6 Mar. 2011. <http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ROME/CRISIS.HTM>. Shelton, Jo-Ann. As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. Theroux, Marcel. "The Politico." The New York Times 22 Oct. 2006. Web. 20 Mar. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/22/books/review/Theroux.t.html?_r=1>.