* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download "Climate Agenda: Resilient, Prosperous, and Green

Fred Singer wikipedia , lookup

Climate resilience wikipedia , lookup

Climate sensitivity wikipedia , lookup

Energiewende in Germany wikipedia , lookup

General circulation model wikipedia , lookup

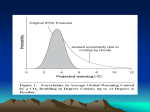

Global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change feedback wikipedia , lookup

Media coverage of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Tuvalu wikipedia , lookup

Attribution of recent climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change adaptation wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Economics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

United Nations Climate Change conference wikipedia , lookup

Economics of climate change mitigation wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

Paris Agreement wikipedia , lookup

2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on Australia wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change, industry and society wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Low-carbon economy wikipedia , lookup

Politics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

German Climate Action Plan 2050 wikipedia , lookup

Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme wikipedia , lookup

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report wikipedia , lookup

Mitigation of global warming in Australia wikipedia , lookup