* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chapter 3 – The Molecules of Cells

Expanded genetic code wikipedia , lookup

Genetic code wikipedia , lookup

Deoxyribozyme wikipedia , lookup

Circular dichroism wikipedia , lookup

Cell-penetrating peptide wikipedia , lookup

Fatty acid metabolism wikipedia , lookup

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of proteins wikipedia , lookup

Protein adsorption wikipedia , lookup

Protein structure prediction wikipedia , lookup

Metalloprotein wikipedia , lookup

Proteolysis wikipedia , lookup

Biosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

Nucleic acid analogue wikipedia , lookup

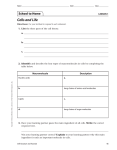

Organic Chemistry Organic chemistry is the study of carbon-based molecules. Nearly all of the compounds that a cell makes are composed of carbon bonded to other carbon atoms and to atoms of other elements. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Organic Chemistry Carbon is unparalleled in its ability to form large, diverse molecules. Recall that carbon has six electrons: – 2 in its innermost shell and 4 in its outermost shell C Carbon completes its outer shell by sharing electrons with other atoms in 4 covalent bonds. Organic Chemistry The diversity of carbon molecules is the driving force behind the myriad of molecules and chemical processes required for life, and explains the great diversity of life on Earth! Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Organic Chemistry Carbon can share its electrons with four hydrogen atoms, creating CH4 or methane. Methane is an example of an organic compound and is the simplest of all organic compounds. H H C H H Organic Compunds • When Carbon shares electrons with Hydrogen atoms, a hydrocarbon results • Hydrocarbons are the major components of petroleum • Petroleum (crude oil) consists of the partially decomposed remains or organisms that lived millions of years ago • This is why the burning of fossil fuels increases carbon dioxide into our atmosphere CH4 + 2 O2 → 2 H2O + CO2 + Energy Organic Chemistry The unique properties of an organic compound depend upon the size and shape of its carbon skeleton and the groups of atoms that are attached to that skeleton. Of the six groups of atoms that are essential to life, five serve as functional groups. Functional groups affect a molecule’s function by participating in chemical reactions in characteristic and predictable ways. carbon skeleton: the chain of carbon atoms in an organic molecu Hydroxyl group – polar, consists of a Hydrogen bonded to an Oxygen Carbonyl group – polar, Carbon linked by a double bond to an Oxygen Carboxyl group – polar, a Carbon double-bonded to both an Oxygen and a Hydroxyl group Amino group – polar, composed of a Nitrogen bonded to 2 Hydrogen atoms and the Carbon skeleton Phosphate group – polar, consists of a Phosphorus atom bonded to 4 Oxygen atoms Methyl group – nonpolar and not reactive,Carbon bonded to 3 Hydrogen Same structure, but different functional groups Estradiol – female sex hormone Methyl group Female Lion Hydroxyl group Carbonyl group Testosterone – male sex hormone Male Lion Besides water, all biological molecules are organic, or carbon-based. There are many organic molecules, but most of the human body is made up of just four types: carbohydrates, lipids, proteins and nucleic acids. Carbohydrates, lipids, proteins and nucleic acids are called macromolecules, and are the building blocks of cells and their chemical machinery. Cells make most of these large molecules by joining together smaller molecules, or monomers, into chains called polymers. Polymer Monomer Nucleic Acid Cellular structure Chromosome DNA strand Nucleotide The key to the great diversity of macromolecules is in the arrangement of its monomers. DNA is built up of only four monomers (nucleotides), and proteins are made with only twenty monomers (amino acids), but both macromolecules are incredible diverse. The proteins in you and a fungus are made with the same twenty amino acids! A cell links monomers together to form polymers by way of a dehydration reaction. A dehydration reaction is so named because it results in the removal of a water molecule. An unlinked monomer has a hydroxyl group (--OH) at one end, and a hydrogen atom (--H) at the other end. Hydrogen atom Hydroxyl group Dehydration Reaction polymer Hydrogen atom monomer Hydroxyl group By removing the hydroxyl group of the polymer, and the hydrogen atom of the monomer that is being added, a water molecule is released. Dehydration Reaction Water molecule Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Just as removing a water molecule links monomers together (to form polymers), the addition of a water molecule breaks a polymer chain apart (releasing a monomer). The process of breaking up polymers is called hydrolysis. Hydrolysis is essentially the reverse of a dehydration reaction. Hydrolysis is necessary to break down polymers that are too large to enter a cell otherwise. Hydrolysis Water molecule Hydrogen atom Hydroxyl group shorter monomer Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Hydrolysis Note that the addition of a water molecule results in the reinstatement of a hydroxyl group at the detached end of the polymer, and the hydrogen atom at the detached end of the newly formed monomer. Hydroxyl group shorter Hydrogen atom monomer Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Enzymes • Both dehydration reactions and hydrolysis require the help of enzymes to make and break bonds • Enzymes are specialized proteins that speed up the chemical reactions in cells • Enzymes are extremely important – without them, many reactions cannot take place. If you lack lactase, you cannot hydrolyze the bond in lactose Carbohydrates are polymers made up of Carb ohydr carbon, hydrogen hydrogen, and oxygen oxygen atoms. carbon Carbohydrates play important roles in the energy storage and structural support of organisms, and are themselves an excellent source of energy. The monomers that make up carbohydrates are called monosaccharides. A monosaccharide is a small sugar, that can link together to form larger, more complex sugars. Monosaccharides generally contain carbon, hydrogen and oxygen in a ratio of 1:2:1. Glucose, the sugar that carries energy to the cells of your body, is a monosaccharide with the chemical formula of C6H12O6. Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. When two monosaccharides are linked together by dehydration synthesis, they form a disaccharide. Examples of disaccharides include the table sugar sucrose, the milk sugar lactose, and maltose which is formed by linking two glucose molecules together. Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Recall that all polymers are built by a dehydration reaction. Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Monosaccharides can also be linked together to form polysaccharides. A polysaccharide is a large polymer consisting of hundreds or thousands of monosaccharides linked by dehydration reactions. Polysaccharides function as storage molecules or structural compounds. The most common types of polysaccharides are starch, glycogen, cellulose, and chitin. Polysaccharide: Starch Starch is an energy storage polysaccharide used by plants. Starch consists entirely of repeating glucose monomers. glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose glucose Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Through the process of photosynthesis, plants produce glucose as an energy source. Often, a plant produces more glucose than is readily needed, so the plant stores this energy as long chains of glucose molecules, or starch! Starch is found in potatoes and grains, such as wheat, corn and barley. Polysaccharide: Glycogen Glycogen is an energy storage polysaccharide used by animals. Glycogen also consists entirely of repeating glucose monomers, but is much longer and more branched than starch. Glycogen is broken down into glucose as energy is needed. Polysaccharide: Cellulose Cellulose is a structural polysaccharide used by plants. Cellulose is the most abundant organic compound on Earth, forming the cell walls of all plant cells. Polysaccharide: Cellulose Cellulose consists of long chains of glucose molecules linked in such a way that they can not be broken down easily. Humans are unable to digest cellulose and it makes up the fiber in our diets. Certain microbes can digest cellulose, and reside in the guts of herbivores, such as cows, sheep, and even termites! Cellulose 1 2 3 4 Polysaccharide: Chitin Chitin is a structural polysaccharide used by animals. Animals that use chitin for external skeletons include insects and crustaceans. Fungi also have chitin in their cell walls for structural support. Chitin attaches to proteins forming a tough and resistant protective material. Chitin forms the exoskeleton of crustaceans such as crabs and lobsters, as well as insects and spiders! Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Animal s Plants Glycogen Starch Chitin Cellulose Storag e Structure Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Lipids • For short-term energy storage, animals convert glucose into glycogen. • For long-term storage, however, organisms usually convert sugars into fats, or lipids. • Lipids are a diverse group of molecules that includes oils, fats, waxes, phospholipids, and steroids. • All lipids are insoluble in water because they are non-polar. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Lipids • Lipids are important for energy storage because they contain many more energy-rich C-H bonds than carbohydrates. • A gram of lipids contains twice as much energy as a gram of polysaccharides, such as starch. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Lipids: Fats • Fats are made up of 2 smaller molecules: glycerol and fatty acids. • A fat molecule contains 1 glycerol and 3 fatty acids. • For this reason, fats are called triglycerides. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Lipids: Fats • A fatty acid consists of a long chain of carbon and hydrogen atoms. • The arrangement of these atoms can vary, affecting the fat molecule’s physical properties. • Fats whose fatty acids contain the maximum number of hydrogen atoms that can fit are called saturated fats. Lipids: Fats • Fats whose fatty acids contain double bonds between some of the carbon atoms are called unsaturated fats because they contain fewer than the maximum amount of hydrogen atoms. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Lipids: Fats • The double bonds (C=C) in unsaturated fats cause kinks, or bends, in the carbon chains of the fatty acids. • These kinks prevent the molecules from packing tightly together so unsaturated fats (like corn oil) remain liquid at room temperature. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Lipids: Fats • In contrast, saturated fats have no double bonds (or kinks). • The molecules can then pack more tightly together, so saturated fats (like butter) are solid at room temperature. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Who You Calling Fat?! • Triglycerides (fats and oils): – Store energy – Insulate (blubber, etc) – Provide cushioning – Prevent dehydration – Help to maintain internal temperature Lipids: Phospholipids • Phospholipids are structurally similar to fats, but contain only 2 fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule. • Each phospholipid molecule has a polar, or hydrophilic end, and a non-polar, or hydrophobic end. • Phospholipids are the main component of cellular membranes. Lipids: Phospholipids • The polar, or hydrophilic end of a phospholipid is “water-loving” and water soluble. • The non-polar, or hydrophobic end of a phospholipid is “waterfearing” and water insoluble. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Lipids: Phospholipids • The membranes of all cells are composed of two layers of phospholipids, called a bi-layer. • The polar, hydrophilic ‘heads’ face outward and are in contact with the aqueous environment on either side of the membrane. • The non-polar, hydrophobic ‘tails’ cluster together in the middle of the membrane. Lipids: Phospholipids Hydrophilic head Hydrophobic tails Water (outside of cell) Water (inside of cell) Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Lipids: Steroids • A steroid is a type of lipid that does not contain fatty acids. • Instead, steroids are composed of 4 carbon rings fused together. 3 1 4 2 4 Carbon Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Lipids: Steroids • Cholesterol is a common steroid found in animal cell membranes. • Cholesterol is also part of some sex hormones like testosterone, estrogen and progesterone. Cholester ol Testosteron e Estroge n Proteins • Proteins are a very diverse group of organic molecules. The many shapes of protein molecules allow them to perform a variety of functions. • In living organisms, they are used for transport, structure, metabolism, communication, and even to detect stimuli such as light. • The protein hemoglobin carries oxygen in your blood, and the protein keratin helps support your skin, hair and nails. Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Amino Acids • Like other organic polymers, proteins are made of many monomers bonded together. • These monomers are called amino acids, and there are 20 different kinds found in protein molecules. • Every amino acid molecule contains an amino group (--NH2) and a carboxyl group (--COOH). Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Amino acids are linked together via dehydration synthesis. The bonds between amino acid monomers are called peptide bonds. Peptide bond Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Proteins • A polypeptide contains hundreds or thousands of amino acids linked together by peptide bonds. • The unique combination of amino acids in a protein molecule determines its specific shape, or structure. • The shape of a protein determines its specific function. Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Every protein has four levels of structure: • Primary • Secondary • Tertiary • Quaternary Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Primary Structure • The primary structure of a protein describes its unique sequence of amino acids. • The primary structure is determined by the cell’s genetic information (DNA). Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Secondary Structure • The secondary structure of a protein describes its folding pattern. • Chains of polypeptides may fold into shapes like a pleated sheet or an alpha helix Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Secondary Structure • The many hydrogen bonds within the polypeptide chain of silk fibers make spider fiber as strong as steel; uses of silk proteins include fishing line, surgical thread and bulletproof vests! Tertiary Structure • The tertiary structure of a protein describes its overall 3-dimensional shape. • This includes all of the pleated sheets and alpha helixes and is the active form of the protein. Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Quaternary Structure • The quaternary structure of a protein describes the complex association of multiple polypeptide chains. • Not all proteins consist of 2 or more polypeptide chains, but those that do have a quaternary structure. • Each polypeptide chain in the association has its own primary, secondary, and tertiary structures. Quaternary Structure Primary structure Secondary structure Quaternary structure Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Quarternary Structure Polypeptide chain • Collagen is formed by several polypeptide chains in a rope-like arrangement • Gives connective tissue, bone, tendons, and ligaments its strength! • Hemoglobin is another example of a quarternary structure protein (transports oxygen in blood) Collagen Protein shape determines function • When exposed to excessive heat, or changes in salinity or pH, a protein can denature. • Denaturation causes the Properly-folded protein polypeptide chains in a protein to unravel, and lose their specific shape. • When this happens, a protein will no longer function normally. Denaturatio n Denature d protein Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Enzymes • Enzymes are proteins that increase the rate of chemical reactions and so are called catalysts. • Like other proteins, the structure of enzymes determines what they do. • Since each enzyme has a specific shape, it can only catalyze a specific chemical reaction. • The digestive enzyme pepsin, for example, breaks down proteins in your food, but can’t break down lipids or carbohydrates. Images : Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc. Proteins gone bad • So what happens is a protein folds incorrectly? • Many diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s involve an accumulation of misfolded proteins • Prions are infectious agents composed of proteins • Prion diseases are currently untreatable and always fatal Prions • Prions infect and propogate by refolding abnormally into a structure that is able to convert normally-folded molecules into abnormally-structured form • This altered form accumulates in infected tissue, causing tissue damage and cell death • Prions are resistant to denaturation due to their extremely stable, tightly packed structure Prions • Prions are implicated in a number of diseases in a variety of mammals: – Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (“Mad Cows Disease”) – spread by feed containing ground-up infected cattle – Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease – degenerative neurological disorder spread by skin grafts or human growth hormone products; Kuru is a similar disease spread by cannibalism among the Fore tribe of Papua New Guinea Prions • Chronic Wasting Disease – found in deer, moose, elk in U.S. and Canada • Fatal Familial Insomnia – very rare, inherited prion disease (50 families worldwide have the responsible gene mutation); insoluble protein causes plaques to develop in the thalamus, the region of brain responsible for the regulation of sleep; fatal within several months Proteins gone bad (or maybe not…) • Sickle cell anemia is caused by a genetic mutation of hemoglobin (not a prion); causes a sickling of the red blood cell • Those with 2 copies of the mutated gene have a reduced life expectancy; those with only 1 copy have “Sickle trait” – cells only sickle under reduced oxygen load • Sickle cell disease common in tropical and subtropical regions where malaria is common; provides a selective advantage against malaria! Sickle Cell Anemia • Remember natural selection is a pessimistic process • Those with the sickle cell mutation survive malaria infestation better than those without • “Heterozygous advantage” Normal red blood cell Sickle blood cells Nucleic Acids • Nucleic acids are molecules, like DNA, that store genetic information - the instructions cells need to build proteins. • A nucleic acid contains information on what type of amino acids are needed to make a protein and in what order they should be linked to give the protein its structure, and function. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Nucleotides • The monomers that are linked together to form a nucleic acid polymer are called nucleotides. Chromosome Every chromosome in our cells contains nucleic acids Polymer = nucleic acid Nucleic acids are polymers Monomer = nucleotide Many nucleotide monomers make up each nucleic acid Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Nucleotides • Every nucleotide has three parts: – 5-carbon sugar – Phosphate group – Nitrogenous base Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Nucleotides • Nucleotides can encode information because they contain more than one type of nitrogenous base. • There are 5 different nitrogenous bases: Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Nucleotides Pyrimidines Cytosine Thymine Uracil Purines Adenine Guanine Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Nucleic Acids • There are two types of nucleic acids: –RNA –DNA Nucleic Acids • There are two types of nucleic acids: – RNA = ribonucleic acid – DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid • Both are nucleotide polymers but they differ in both their structures and their functions. RNA • Ribonucleic acid contains the sugar ribose. • RNA contains the nucleotide uracil (U) instead of the nucleotide thymine (T). RNA contains: • adenine (A) • uracil (U) • cytosine (C) • guanine (G) Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. RNA Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. RNA • RNA exists as a long, single strand of nucleotides. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. DNA • In deoxyribonucleic acid, a hydroxyl group on the sugar is replaced with a hydrogen atom. • DNA contains the nucleotide thymine (T) instead of the nucleotide uracil (U). DNA contains: • adenine (A) • thymine (T) • cytosine (C) • guanine (G) Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. DNA Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. DNA • DNA exists as a two strands of nucleotides wound around each other to form a double helix. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. The Double Helix • DNA’s double helix results from hydrogen bonds formed between its nitrogenous bases. • Large nitrogenous bases (adenine and guanine) pair with smaller bases (thymine and cytosine). • Adenine bonds with thymine (A-T) and guanine bonds with cytosine (G-C). The Double Helix • Because of its A-T, G-C pairing, each DNA strand is complimentary to the other. • If the sequence of one strand is ATCGAT, the sequence of the other strand must be TAGCTA because A always bonds to T, and C always bonds to G. Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. DNA Double Helix Images : Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. DNA double helix • The 2 DNA chains are held in a double helix by hydrogen bonds between their paired bases • Most DNA molecules have thousands or millions of base pairs – (A and T would be considered a base pair; as would C and G) Hydrogen bonds (dotted lines)