* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Severe aortic stenosis in a Persian kitten Estenose aórtica

Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Marfan syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Turner syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Echocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Mitral insufficiency wikipedia , lookup

Congenital heart defect wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

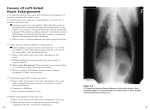

CASO CLÍNICO R E V I S TA P O R T U G U E S A DE CIÊNCIAS VETERINÁRIAS Severe aortic stenosis in a Persian kitten Estenose aórtica severa em um gato Persa Marlos G. Sousa1*, João Paulo da E. Pascon2, Alexandre M. de Brum3, Priscila A. C. Santos2, Aparecido A. Camacho2 1 College of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, The Federal University of Tocantins (UFT), Campus of Araguaína, Brazil 2 College of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences, São Paulo State University (UNESP), Campus of Jaboticabal, Brazil 3 College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Franca (UNIFRAN), Franca, Brazil Summary: A case of severe aortic stenosis in a kitten is reported. Although no obvious clinical signs were observed initially, congestive left heart failure developed seven months later. On presentation, severe pulmonary edema was diagnosed and an incidental thrombus within the enlarged left atrium was disclosed on echocardiographic examination. Clinical features and diagnostic methods are discussed in this paper. Keywords: congenital heart disease, echocardiography, thromboembolism, concentric hypertrophy, pulmonary edema Resumo: Relata-se um caso de estenose aórtica severa em um gato Persa. Apesar da inexistência de sinais clínicos inicialmente, desenvolveu-se insuficiência cardíaca congestiva sete meses após o atendimento inicial, sendo diagnosticado edema pulmonar e, ao exame ecocardiográfico, um trombo incidental no interior do átrio esquerdo dilatado. Neste artigo, são discutidas as características clínicas e os métodos diagnósticos empregados nesse caso de cardiopatia congênita. Palavras-chave: doença cardíaca congênita, ecocardiografia, tromboembolismo, hipertrofia concêntrica, edema pulmonar Introduction Aortic stenosis is a congenital narrowing of the left ventricular outflow tract, aortic valve, or supravalvular aorta (Bolton and Liu, 1977; Liu, 1977; Kienle, 1998). Wherever it is located, obstruction to left ventricular outflow increases left ventricular systolic pressure, resulting in concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle (Sisson et al., 2000). Although reported as one of the most common congenital heart disease in dogs, aortic stenosis has only been described in a few cats (Liu, 1968; Stepien * Correspondence: [email protected] BR 153, Km 112, Campus EMVZ/UFT, Araguaína, TO, Brazil, 77804-970 Tel: +55 (63) 2112 2113; Fax: +55 (63) 2112 2136 and Bonagura, 1991; King, 1997). To date, Harpster (1986) has documented this defect to count for only 6% of all congenital heart disease in domestic felines. The increased left ventricular systolic pressure propels blood at a higher velocity across the stenotic area, thereby resulting in a turbulent flow that is associated with a systolic ejection murmur (Bolton and Liu, 1977; Stepien and Bonagura, 1991), which may eventually be accompanied by a soft diastolic murmur secondary to aortic valve insufficiency (Sisson et al., 2000). Clinical signs may be absent in many mildly-tomoderately affected patients, and most affected cats are recognized when an ejection murmur is auscultated at the time of initial vaccinations (Bonagura, 1994; Kienle, 1998). In severely affected animals, exertional fatigue, syncope, and even signs related to congestive heart failure may be observed (Stepien and Bonagura, 1991; Kienle, 1998). Definitive diagnosis of aortic stenosis requires angiocardiography, or echocardiography (Bonagura, 1994). A fibrous obstructing lesion, left ventricular concentric hypertrophy, and post-stenotic dilatation may be observed on two-dimensional echocardiography (Belerenian, 2007; Ferraris, 2007). Doppler echocardiography should reveal an increased peak velocity of aortic flow. In dogs, Sisson et al. (2000) documented that aortic velocity over 2.2 m/s is regarded as indicative of aortic stenosis, whereas in cats, Stepien and Bonagura (1991) reported that peak aortic velocity greater than 2 m/s might suggest a narrowed aortic tract. As documented in literature, aortic stenosis is an uncommon congenital heart defect in cats. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to report a case of severe aortic stenosis in an initially asymptomatic Persian kitten, followed by the development of left atrial thrombus and signs of congestive heart failure. 229 Sousa MG et al. RPCV (2008) 103 (567-568) 229-232 Case description A 5-month-old male Persian kitten weighing 2.5 kg was brought to consultation for initial vaccination. Except for a grade 3/6 systolic ejection murmur heard best over the left basilar region and radiating both cranially and dorsally, no obvious abnormalities were found on physical examination. The caretaker noted that the kitten had an adequate appetite and was as active as its sibling. Although the cat had demonstrated normal behavior and physical activity with no overt medical conditions, ancillary exams were requested to investigate the murmur. Thoracic radiographs disclosed a normal cardiac silhouette and no evidence of congestive heart failure. Cardiac examination consisted in a 6-lead computerized electrocardiogram and echocardiography with Doppler examination. Only sinus tachycardia was documented on electrocardiography (200 bpm). Echocardiography was performed from the right parasternal and left apical locations. On two-dimensionally-guided M-mode echocardiography, a mildly decreased left ventricular systolic diameter (0.55 cm), decreased left ventricular diastolic diameter (1.26 cm), and increased fractional shortening (56%) were consistent with mild left ventricular concentric hypertrophy. Left atrial diameter was within the reference range. On the apical five-chamber view, a severely increased peak aortic velocity (6.03 m/s) was identified using continuous-wave Doppler (Figure 1). Based on the echocardiographic findings, the diagnosis of aortic stenosis was established. Four months later, the cat was brought to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital for a follow-up consultation. On presentation, he weighed 4.7 kg, was very active and his owner reported no abnormalities since we last saw him. We auscultated a grade 4/6 systolic ejection murmur, still radiating cranially and dorsally, but the remainder of the physical examination findings were unremarkable. M-mode echocardiography showed a moderate left atrial enlargement (1.74 cm, with a left atrium-to-aorta ratio of 2.3), increased interventricular septal thickness in systole (0.98 cm) and diastole (0.89 cm), and decreased left ventricular systolic (0.55 cm) and diastolic diameter (1.00 cm). Color-flow and spectral Doppler demonstrated a highvelocity turbulent flow across the aorta. Three months later, the cat was presented to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital emergency service with acute difficulty in breathing and tachypnea. On physical examination, the patient had mildly cyanotic mucous membranes, and was tachypneic, dyspneic, and tachycardic. Peripheral pulse rate matched the heart rate at 210 pulses/minute. Cardiac sounds were inaudible over pulmonary crackles and wheezes. Lateral radiographs showed severe pulmonary edema and left atrial enlargement. Short-term emergency therapy was immediately initiated and included 230 Figure 1 – Continuous-wave Doppler interrogation at initial presentation showed a severely increased peak aortic velocity (6.03 m/s) and a turbulent flow across the aortic valve (arrow). (Ao: Aorta; LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle). Figure 2 – Echocardiographic findings in a kitten with aortic stenosis: Left atrial thrombus (between arrows) seen on the long-axis view. (LA: left atrium; RA: right atrium; LV: left ventricle). furosemide and a nitroglycerin transdermal patch placed over a shaved area on lateral thorax. The patient was continually supplemented with 100% oxygen via a face mask, resulting in improvement in the color of the mucous membranes. An ultrasonographic examination of the heart disclosed a large thrombus (approximately 0.94 x 0.52 cm) (Figure 2) inside the severely enlarged left atrium (2.38 cm). Due to respiratory distress, the echocardiogram was not fully performed. Therefore, no measures of left ventricular chamber and aortic peak velocity were done at this time. Although every effort was made to treat pulmonary edema, cardiopulmonary arrest occurred about three hours after initial presentation. Sousa MG et al. Discussion Congenital cardiac disease comprises about 10% of cardiology cases in domestic mammals (Keirstead et al., 2002). In cats, however, congenital heart diseases are less common, counting for approximately 0.02% to 0.1% of hospital admissions (Goodwin, 2001). Although rare, some reports of congenital fixed aortic stenosis in cats exist (Liu, 1968; Stepien and Bonagura, 1991). Although no clinical signs were observed at initial presentation, a congenital heart disease was suspected due to a loud systolic ejection murmur loudest over the left basilar region. Cote et al. (2004) reported that many murmurs detectable in overtly healthy cats appear to be caused by a latent structural heart disease. Because young animals can have physiologic or innocent heart murmurs, it is important to consider that, in general, loud heart murmurs are indicative of cardiac disease (Kittleson, 1998). Therefore, ancillary exams were requested to confirm the suspected heart pathology. Initial thoracic radiographs did not show any abnormalities. Left ventricular enlargement and widening of the mediastinum (poststenotic dilatation) may be detected by radiography in severely affected animals (Liu, 1968; Bolton and Liu, 1977; Stepien and Bonagura, 1991). In some cases, however, thoracic radiographs may be normal (Sisson et al., 2000). Only sinus tachycardia was observed on the electrocardiogram. Although the electrocardiogram is generally normal in dogs with subaortic stenosis, severely affected dogs may eventually have ventricular premature contractions (Kienle, 1998). Nevertheless, we did not observe any abnormality in nearly three minutes of ECG recording in this cat. The suspected congenital heart anomaly was confirmed by Doppler echocardiography. The highly increased velocity across aortic valve is the definitive diagnosis of aortic stenosis (Stepien and Bonagura, 1991; Ferraris, 2007), which has been recognized to occur in subvalvular, valvular, and supravalvular forms in cats (Kienle, 1998). Also, an incomplete subaortic stenotic ring was detected at necropsy in one cat (King et al., 1988). The obstruction was assumed to be fixed rather than dynamic owing to the lack of a delayed systolic peak in the continuous-wave Doppler tracing of the left ventricular outflow tract (Thomas et al., 1984; Kienle, 1998). Chronic pressure overload associated to a normal or enhanced myocardial function resulted in secondary left ventricular concentric hypertrophy, which is usually appreciated in moderately-to-severely affected animals (Kienle, 1998). Interestingly, no poststenotic dilatation was recognized. In dogs, however, the dilatation may be slight before 6 months of age (Kienle, 1998), which is likely to be similar in affected cats. Due to questionable or unproven value, medical RPCV (2008) 103 (567-568) 229-232 therapy was not initiated in this kitten (Fox, 1991; Bonagura, 1994). Although the kitten was asymptomatic and had no electrocardiographic abnormalities, the owner was informed of the possibility of starting a beta-adrenergic receptor blocking drug and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor empirically (Kienle, 1998; Sisson et al., 2000; Belerenian, 2007), since a severely increased gradient was measured across aortic valve. By decreasing heart rate and cardiac contractility, beta-blockers may reduce myocardial oxygen demand and increase coronary perfusion, thereby reducing the occurrence of malignant arrhythmias (Kienle, 1998). However, this option was declined and only restriction to vigorous exercise was recommended. Cats with cardiac disease are prone to develop thromboembolism (Laste and Harpster, 1995; Smith and Tobias, 2004). In general, the thrombus is formed in the enlarged left atrium due to blood stasis, endothelial damage, and altered coagulability (Pion and Kittleson, 1989; Bonagura, 1994). In the case reported herein, the abnormal diastolic filling pattern as a consequence of concentric hypertrophy and ventricular stiffness resulted in left atrial enlargement, therefore predisposing for thrombogenesis (Bonagura, 1994; Kienle, 1998). On presentation, however, the thrombus had not caused clinical abnormalities and was an incidental finding. The thrombus within left atrium was large enough to be easily observed on standard long-axis four-chamber and short-axis views. Although reports of intracardiac thrombi exist (Venco, 1997), we did not find any report of intracardiac thrombus formation in a cat with aortic stenosis. Conclusion Although rare, aortic stenosis may occur in cats. Loud heart murmurs auscultated in overtly healthy kittens may indicate a congenital heart disease. Therefore, clinicians are reminded to perform a detailed physical examination prior to routine vaccinations or exams. Also, cats with aortic stenosis and enlarged left atrium should be considered at risk for developing intracardiac thrombi and even thromboembolism. Bibliography Belerenian G (2007). Estenosis aórtica. In: Afecciones cardiovasculares en pequeños animales. Editors: Belerenian G, Mucha CJ, Camacho AA, Grau JM. Intermédica (Buenos Aires), 227-236. Bolton GR, Liu SK (1977). Congenital heart disease of the cat. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract, 7: 341-353. Bonagura JD (1994) Cardiovascular diseases. In: The cat: diseases and clinical manangement. Editors: Sherding RG. Churchill Livingstone (New York), 819-946. 231 Sousa MG et al. Coté E, Manning AM, Emerson D, Laste NJ, Malakoff RL, Harpster NK (2004). Assessment of the prevalence of heart murmurs in overtly healthy cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc, 225: 284-388. Ferraris SR (2007). Ecocardiografía. In: Afecciones cardiovasculares en pequeños animales. Editors: Belerenian G, Mucha CJ, Camacho AA, Grau JM. Inter-médica (Buenos Aires), 129-177. Fox PR (1991). Evidence for or against efficacy of betablockers and aspirin for management of feline cardiomyopathies. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract, 21: 1011-1022. Goodwin JK (2001). Congenital heart disease. In: Manual of canine and feline cardiology. Editors: Tilley LP, Goodwin JK. Saunders (Philadelphia), 273-293. Harpster NK (1986) The cardiovascular system. In: Diseases of the cat. Editor: Holzworth J. Saunders (Philadelphia), 820-933. Keirstead N, Miller L, Bailey T (2002). Subvalvular pulmonary stenosis in a kitten. Can Vet J, 43: 785-786. Kienle RD (1998) Aortic stenosis. In: Small animal cardiovascular medicine. Editors: Kittleson MD, Kienle RD. Mosby (Saint Louis), 260-272. King JM, Flint TJ, Anderson WI (1988). Incomplete subaortic stenotic rings in domestic animals – a newly described congenital anomaly. Cornell Vet, 78: 263-271. King JM (1997) Subaortic stenosis ring in a cat. Vet Med, 92: 236. Kittleson MD (1998). The approach to the patient with 232 RPCV (2008) 103 (567-568) 229-232 cardiac disease. In: Small animal cardiovascular medicine. Editors: Kittleson MD, Kienle RD. Mosby (Saint Louis), 195-217. Laste NJ, Harpster NK (1995). A retrospective study of 100 cases of feline distal aortic thromboembolism: 19771993. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc, 31: 492-500. Liu SK (1968). Supravalvular aortic stenosis with deformity of the aortic valve in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc, 152: 55-59. Liu SK (1977). Pathology of feline heart diseases. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract, 7: 323-339. Pion PD, Kittleson MD (1989). Therapy for feline aortic thromboembolism. In: Current veterinary therapy. Editor: Kirk RW. Saunders (Philadelphia), 295-302. Sisson DD, Thomas WP, Bonagura JD (2000). Congenital heart disease. In: Textbook of veterinary internal medicine: diseases of the dog and cat. Editors: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC. Saunders (Philadelphia), 737-787. Smith SA, Tobias AH (2004). Feline arterial thromboembolism: an update. Vet Clin Small Anim, 34: 1245-1271. Stepien RL, Bonagura JD (1991). Aortic stenosis: clinical findings in six cats. J Small Anim Pract, 32: 341-350. Thomas WP, Mathewson JW, Suter PF, Reed JR, Meierhenry EF (1984). Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy in a dog: clinical, hemodynamic, angiographic, and pathologic studies. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc, 20: 253-260. Venco L (1997). Ultrasound diagnosis: left ventricular thrombus in a cat with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Vet Radiol Ultrasound, 38: 467-468.