* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download moral philosophy - The Richmond Philosophy Pages

Arthur Schafer wikipedia , lookup

J. Baird Callicott wikipedia , lookup

Aristotelian ethics wikipedia , lookup

Individualism wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg wikipedia , lookup

Divine command theory wikipedia , lookup

Happiness economics wikipedia , lookup

Virtue ethics wikipedia , lookup

Moral development wikipedia , lookup

Moral disengagement wikipedia , lookup

Bernard Williams wikipedia , lookup

Alasdair MacIntyre wikipedia , lookup

Ethics in religion wikipedia , lookup

School of Salamanca wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development wikipedia , lookup

Morality and religion wikipedia , lookup

Ethics of artificial intelligence wikipedia , lookup

Morality throughout the Life Span wikipedia , lookup

Ethical intuitionism wikipedia , lookup

Moral relativism wikipedia , lookup

Hedonic treadmill wikipedia , lookup

Moral responsibility wikipedia , lookup

Secular morality wikipedia , lookup

Thomas Hill Green wikipedia , lookup

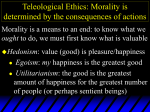

MORAL PHILOSOPHY DECISIONS AND TRUTH Moral philosophy or ethics… (1) Normative ethics. Theories addressing the questions of how we ought to act or how we should be. What is the basis on which we should make decisions about what we ought to do. The central concern of normative ethics is an elucidation of what is right, good or virtuous. (2) Meta-ethics. Theories concerning the nature of moral judgements. Key questions focus on whether our moral statements can be true or false or whether moral judgements are instead basically subjective expressions of feeling, attitude or agreement. The implications for moral knowledge and moral psychology (motivation). (3) Applied ethics. The examination of and attempt to understand practical moral problems such as abortion, euthanasia, animal welfare, suicide, poverty, the environment (and our relationship to it)… Normative ethics Key questions: (1) what should one do? (2) How should one be? These questions are not equivalent. Difference on what is at the centre of ethical reasoning. (1) places our actions centre-stage. Ethical theory articulates the criterion(a) by which actions and so persons are judged. An action may be evaluated in terms of its good or bad consequences. Or, it may be judged as the right or wrong thing to do by reference to the motivations of the agent and her duties. (2) begins with the idea of what makes for a flourishing or worthwhile life. This is not to ignore the necessity and importance of acting, but rather locates action and agency within an account of the psychology and social relations constitutive of the good life for an individual. The first conception finds expression in consequentialist and deontic (duty-based) theories and the second in virtue theory. Three big theories 1. 2. 3. Utilitarianism – maximising the good consequences. Deontology – acting in accordance with duty. Virtue ethics – possessing a virtuous character. Utilitarianism Utilitarianism is a consequentialist theory. The moral evaluation of actions depends on the goodness or badness of their consequences: the good is prior to the right. Teleological or goal directed approach – an action is good if it produces good outcomes Outcomes evaluated from an impartial standpoint to determine best-worst. Utilitarian theories… Roughly – • • • Act - do that act which taken on its own will maximise general happiness. Rule - act in accordance with rules, the adherence to which will maximise general happiness. Preference - act so as to satisfy people’s preferences. Classical utilitarianism: Bentham and hedonic act utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) – social reformer and campaigner. The right thing to do is determined by a consideration of what action produces the greatest level of overall happiness or utility. Why aim at maximising utility? The consequentialist intuition – it must be better to bring about better rather than worse states of affairs. Plus a theory about the nature of what is valuable Thesis that it is only pleasure or happiness which is intrinsically valuable - valuable in its own right or ‘as such’. One intrinsically valuable state of affairs which is the experience of pleasure. Everything else is extrinsically valuable only in relation the intrinsic value or goodness of pleasure. Underpins the view that morality should aim at the maximisation of the overall level of utility. For what else could its end be? Why aim at maximising utility? … equality A theory focused on maximising outcomes emphasises the equality of individuals. Each person’s interests treated with equal consideration. Taking everyone as morally equal we decide what is right by judging which act maximises overall well-being: people matter and matter equally; each person is given equal weight; so, the act that maximises outcomes is the right one. Maximisation is a means of arriving at a decision which takes each person and their interests as possessed of equal importance. Something like this approach is found in Bentham and Mill. Why aim at maximising utility? Bentham’s picture of human psychology – influenced by the empiricist tradition of Hobbes and Hume. Mankind governed by pain and pleasure. Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure… They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think: every effort we can make to throw off our subjection, will serve but to demonstrate and confirm it. In words a man may pretend to abjure their empire: but in reality he will remain subject to it all the while. The principle of utility recognises this subjection, and assumes it for the foundation of that system. Immediate worries Measurement The nature of utility – is it just how I feel? Hedonic v. non-hedonic (or ideal) accounts of utility. Eating pork pies, watching Eastenders, going to the opera, reading great literature, doing philosophy… Can they be measured by the same yardstick? Sense in which they are equal? Reading ‘Doing the right thing: part 1’ RJP 19 Classical utilitarianism: Mill Development of Bentham – an increased sophistication in our psychology and the components of happiness. On Bentham - Man is never recognised by him as a being capable of pursuing spiritual perfection as an end; of desiring, for its own sake, the conformity of his own character to his standard of excellence, without the hope of good or fear of evil from other source than his inward consciousness. But a fundamental agreement on the greatest happiness principle The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure, and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain, and the privation of pleasure. To give a clear view of the moral standard set up by the theory, much more requires to be said; in particular, what things it includes in the ideas of pain and pleasure; and to what extent this is left an open question. But these supplementary explanations do not affect the theory of life on which this theory of morality is grounded - namely, that pleasure, and freedom from pain, are the only things desirable as ends; and that all desirable things (which are as numerous in the utilitarian as in any other scheme) are desirable either for the pleasure inherent in themselves, or as means to the promotion of pleasure and the prevention of pain. Higher and lower pleasures Connection with Aristotle? Mill not committed to Aristotle's essentialism. He is not seeking to argue from a view of human nature to the conclusion that because certain activities or capacities are essentially human, we therefore ought to lead a certain kind of life. Rather, it is because we have these distinctive capacities that we will not be fully satisfied by any happiness that does not involve their exercise. The Proof - not a formal proof or argument to establish normative truth from naturalistic premises. An attempt to establish plausibility (at least) of principle of utility. Deeper problems… Act utilitarianism is unsustainable. On each occasion, an agent should decide what to do by calculating which act would produce the most good. But – Many agents don’t have the information needed to make the right decision. Obtaining the necessary information might involve greater pain than what is at stake in the dilemma to be resolved. Individuals may well make mistakes, especially if they have a vested interest or they are in a hurry. Expectation effects – if we know everyone else is prepared to break promises, steal, lie, and so on in order to maximise pleasure, then we may find our trust in others destroyed and finish up with a community which is much less likely to produce happiness. So, move to rule utilitarianism But, this faces a coherence challenge. It either permits exceptions to the rules to allow maximisation of outcomes or I must stick to the rules and so am forced to act against the basic utilitarian principle. Two big problems Utilitarianism permits morally horrific acts. Utilitarianism cannot recognise the moral significance of individual integrity and of one’s commitments and projects. Reading – ‘Doing the right thing: part 2’.