* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Recommendations for nondrug therapy

NK1 receptor antagonist wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Psychedelic therapy wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Theralizumab wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Norepinephrine wikipedia , lookup

Drug interaction wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of beta-blockers wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of ACE inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of angiotensin receptor blockers wikipedia , lookup

Psychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

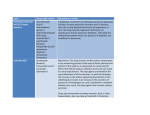

Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD SYSTEMIC HYPERTENSION THERAPY Nondrug Therapy LIFE STYLE MODIFICATIONS Interest in the use of various nondrug therapies, better called life style modifications, for the treatment of hypertension has risen markedly in the past few years, yet many practitioners either do not use them or use them in a casual, perfunctory manner. This hesitant attitude can be attributed both to the sparseness of firm evidence indicating that these therapies succeed and to the difficulty many have faced in convincing patients to adhere to them. This situation is likely to change: Evidence for the effectiveness of these approaches in lowering blood pressure is growing, techniques for improving adherence are being popularized, and patients seem increasingly willing to adopt changes in life style. Recommendations for nondrug therapy Alcohol Obesity Saturated fat Sodium/salt Smoking Exercise Potassium Other Calcium Magnesium Stress management Normotensive individuals Hypertensive patients 2 drinks/day (8 oz. wine, 2 oz. 2 drinks/day (8 oz. wine, 2 oz. liquor, 24 oz. beer) liquor, 24 oz. beer); Abstinence if BP still uncontrolled Goal body weight = BMI 20–27 Reduce to acceptable BMI by diet kg/m˛ and exercise Total fat <30% total calories. Total fat <30% total calories. Saturated fat <10% of total Saturated fat <10% of total calories. Cholesterol <100 mg/ day calories. Cholesterol <100 mg/ day Avoid high salt foods, minimize Avoid high salt foods, minimize salt addition. Reduct intake to salt addition. Reduce intake to <100 mmol (<2.3 g sodium, <6 g <100 mmol (<2.3 g sodium, <6 g salt)/day salt)/day Stop smoking Stop smoking Regular exercise as beneficial for Regular, progressive exercise as weight regulation and reducing beneficial for weight regulation cardiovascular mortality and reducing cardiovascular mortality; avoid isometric exercise Eat a potassium-rich diet (high in Eat a potassium-rich diet (high in vegetables, fruits, low-fat dairy vegetables, fruits, low-fat dairy products) products, especially if on potassium-losing diuretics) Data at present not sufficient to Data at present not sufficient to recommend inclusion recommend inclusion Adapted form Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The Fifth Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC V). Arch Intern Med 1993:154–183; Laidlaw JC, Chockalingam A. Canadian Consensus Conference on Nonpharmacological Approaches to the Management of High Blood Pressure: Recommendations. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1990; 16:S48–S50; and Cressman MD. Management of hypercholesterolemia in the hypertensive patient. Cleve Clin J Med 1989: 56:351–358. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 1 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Stepped Care Over the past two decades, the concept of progressive, stepped care has evolved from a narrow set of incremental options to a broader set of guidelines in JNC-V and VI: Step 1: Prescribe lifestyle modifications, including weight reduction, moderated alcohol intake, regular physical exercise, reduced sodium intake, and smoking cessation; Step 2: If response is inadequate, continue the lifestyle modification and add monotherapy for mild to moderate (Stage 1–2) hypertension with thiazide diuretics, ACE-inhibitors, calcium antagonists, a1blockers, a-b-blockers or b-blockers, unless there is a contra-indication. Step 3: If response to initial treatment is inadequate, increase the drug dose or substitute another antihypertensive drug or add a second agent from a different drug class; Step 4: If response still inadequate, add a second or third agent of a different drug class (including an appropriate diuretic, if not already administered). This approach’s major advantages consist of simplicity of understanding and implementation, emphasis on administration of complementary drug classes for synergism, and titration to minimize toxicities. DIETARY SODIUM RESTRICTION Sodium restriction is useful for all persons, as a preventive measure in those who are normotensive and, more certainly, as partial therapy in those who are hypertensive. The easiest way to accomplish moderate sodium restriction is to substitute natural foods for processed foods, because natural foods are low in sodium and high in potassium whereas most processed foods have had sodium added and potassium removed. Additional guidelines include the following: 1. Add no sodium chloride to food during cooking or at the table. 2. If a salty taste is desired, use a half sodium and half potassium chloride preparation (such as Lite Salt) or a pure potassium chloride substitute. 3. Avoid or minimize the use of “fast foods,” many of which have high sodium content. 4. Recognize the sodium content of some antacids and proprietary medications. 5 Avoid drinking of mineral water. Rigid degrees of sodium restriction are not only difficult for patients to achieve but may also be counterproductive. GENERAL GUIDELINES TO IMPROVE PATIENTS' ADHERENCE TO ANTIHYPERTENSIVE THERAPY 1. Be aware of the problem of nonadherence and be alert to signs of patients' nonadherence. 2. Establish the goal of therapy: to reduce blood pressure to normotensive levels with minimal or no side effects. 3. Educate the patient about the disease and its treatment. a. Involve the patient in decision-making. b. Encourage family support. 4. Maintain contact with the patient. 2 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD a. Encourage visits and calls to allied health personnel. b. Allow the pharmacist to monitor therapy. c. Give feedback to the patient via home blood pressure readings. d. Make contact with patients who do not return. 5. Keep care inexpensive and simple. a. Do the least work-up needed to rule out secondary causes. b. Obtain follow-up laboratory data only yearly unless indicated more often. c. Use home blood pressure readings. d. Use nondrug, no-cost therapies. e. Use the fewest daily doses of drugs needed. f. If appropriate, use combination tablets. g. Tailor medication to daily routines. 6. Prescribe according to pharmacological principles. a. Add one drug at a time. b. Start with small doses, aiming for 5 to 10 mm Hg reductions at each step. c. Prevent volume overload with adequate diuretic and sodium restriction. d. Take medication immediately on awakening or after 4 A.M. if patient awakens to void. e. Ensure 24-hour effectiveness by home or ambulatory monitoring. f. Continue to add effective and tolerated drugs, stepwise, in sufficient doses to achieve the goal of therapy. g. Be willing to stop unsuccessful therapy and try a different approach. h. Adjust therapy to ameliorate side effects that do not spontaneously disappear. From Kaplan NM: Clinical Hypertension. 7th ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1998, p 188. STARTING DOSAGES. The need to start with a fairly small dose also reflects a greater responsiveness of some patients to doses of medication that may be appropriate for the majority. All drugs exert increasing effect with increasing doses. DRUG COMBINATIONS. Combinations of smaller doses of two drugs from different classes have been marketed to take advantage of the differences in the dose-response curves for therapeutic and toxic (side) effects. COMPLETE COVERAGE WITH ONCE DAILY DOSING. A number of choices within each of the six major classes of antihypertensive drugs now available provide full 24-hour efficacy. Therefore, single daily dosing should be feasible for virtually all patients, thereby improving adherence to therapy. THE INITIAL CHOICE. The initial choice of antihypertensive therapy is perhaps the most important decision made in the treatment process. Two guidelines by expert committees have been published: The JNC-VI recommends diuretics or beta blockers as initial therapy for the relatively small portion of patients with uncomplicated hypertension, and drugs from all of the six Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 3 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD major classes for patients with either a compelling indication or a comorbid condition that has been shown to respond well to a particular therapy. The 1999 WHO-ISH guidelines broaden the number of compelling indications but give equal weight to all classes of drugs if there are no specific reasons to use one, stating that “There is as yet no evidence that the main benefits of treating hypertension are due to any particular drug property rather than to lowering of blood pressure per se.” GUIDELINES FOR SELECTING DRUG TREATMENT CLASS OF COMPELLING DRUG INDICATIONS POSSIBLE INDICATIONS COMPELLING CONTRAINDICATIONS POSSIBLE CONTRAINDICATIONS Diuretics Heart failure Elderly patients Systolic hypertension Diabetes Gout Dyslipidemia Sexually active men Beta blockers Angina After myocardial infarction Tachyarrhythmias Heart failure Pregnancy Diabetes Asthma and COPD Heart block* Dyslipidemia Athletes and physically active patients Peripheral vascular disease ACE inhibitors Heart failure Left ventricular dysfunction After myocardial infarction Diabetic nephropathy Calcium antagonists Angina Elderly patients Systolic hypertension Peripheral vascular disease Alpha blockers Prostatic hypertrophy Glucose intolerance Dyslipidemia Angiotensin II antagonists ACE inhibitor cough Heart failure Pregnancy Hyperkalemia Bilateral renal artery stenosis Heart block† Congestive heart failure‡ Orthostatic hypotension Pregnancy Bilateral renal artery stenosis Hyperkalemia *Grade 2 or 3 atrioventricular block; †grade 2 or 3 atrioventricular block with verapamil or diltiazem; ‡verapamil or diltiazem. ACE = angiotensinconverting enzyme; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. DIURETICS In two groups that constitute a rather large portion of the hypertensive population, the elderly and blacks, diuretics may be particularly effective. One-half of a diuretic tablet per day is usually all that is needed, minimizing cost and maximizing adherence to therapy. Even lower doses, i.e., 6.25 mg of hydrochlorothiazide, may be adequate when combined with other drugs. 4 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD The side effects of high-dose diuretic therapy are usually not overly bothersome, but the hypokalemia, hypercholesterolemia, hyperinsulinemia, and worsening of glucose tolerance that often accompany prolonged high-dose diuretic therapy gave rise to concerns about their long-term benignity. However, lower doses are usually just as potent as higher doses in lowering the blood pressure and less likely to induce metabolic mischief. Diuretics useful in the treatment of hypertension may be divided into four major groups by their primary site of action within the tubule, starting in the proximal portion and moving to the collecting duct: (1) agents acting on the proximal tubule, such as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, which have limited antihypertensive efficacy; (2) loop diuretics; (3) thiazides and related sulfonamide compounds; (4) potassium-sparing agents. A thiazide is the usual choice, often in combination with a potassium-sparing agent. Loop diuretics should be reserved for those patients with renal insufficiency or resistant hypertension. SIDE EFFECTS. A number of biochemical changes often accompany successful diuresis, including a decrease in plasma potassium level and increases in glucose, insulin, and cholesterol levels The mechanisms by which chronic diuretic therapy may lead to various complications. The mechanism for hypercholesterolemia remains in question, although it is shown as arising via hypokalemia. Cl = Clearance; PRA = plasma renin activity; GFR = glomerular filtration rate. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 5 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Site of action of diuretics. A common feature of all diuretics is their natriuretic action, which leads to a decrease in total body sodium. The most potent diuretics (furosemide, bumetanide, and ethacrynic acid) decrease sodium resorption in the thick ascending loop of Henle. Urinary sodium excretion can be enhanced considerably with these agents by increasing the dose. Loop diuretics remain effective even in patients with severely impaired renal function. Thiazides, metolazone, and indapamide inhibit sodium resorption in the early portion of the distal convoluted tubule. The dose-response curve to these diuretics is rather flat. Furthermore, the natriuretic effect of thiazides and indapamide is lost when the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is reduced below approximately 40 ml/min, whereas metolazone is still active down to a GFR of approximately 20 ml/min. Loop diuretics, thiazides, and metolazone as well as triamterene, amiloride, and spironolactone act in the late portion of the distal convoluted tubule and the cortical collecting duct. Triamterene and amiloride have weak natriuretic action. 1 = glomerulus; 2 = proximal convoluted tubule; 3 = loop of Henle; 4 = distal convoluted tubule; 5 = collecting duct. 6 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Mechanisms of action of diuretics. Sixty percent of filtered sodium is resorbed in the proximal convoluted tubule (obligatory resorption). The more distal segments of the nephron can modulate excretion of only a fraction of the total filtered sodium. Diuretics that impair sodium resorption in the thick ascending loop of Henle (furosemide, bumetanide, ethacrynic acid) interfere with the Na/K+/2Cl- cotransport system located at the apical membrane of the renal tubule. These diuretics act at a site where a large quantity of sodium is normally resorbed. Thiazides, metolazone, and indapamide inhibit the apical Na +/Cl- cotransport system. Only a small fraction of filtered sodium normally is resorbed at this site of the nephron, which accounts for the limited natriuretic activity of the diuretics. In the distal convoluted tubule and in the cortical collecting duct, sodium is transported at the apical level of the tubular cell through a sodium channel. Sodium is then exchanged against a potassium ion at the basal membrane due to the activity of Na+,K+ -ATPase. The activity of this enzyme is enhanced by aldosterone, the mineralocorticoid hormone secreted by the adrenal glomerulosa. Spironolactone is a competitive antagonist of aldosterone and consequently inhibits pump activity. Amiloride and triamterene block the apical sodium transport. The elimination of potassium is reduced by diuretics acting in these most distal portions of the nephron because of decreased sodium-potassium exchange. In contrast, loop diuretics and diuretics acting in the early distal convoluted tubule increase kaliuresis and tend to cause hypokalemia. This is mainly because these agents enhance delivery of sodium downstream and subsequently accentuate the sodium-potassium exchange. As a result, an increased quantity of sodium is available for resorption in the late distal convoluted tubule and the cortical collecting duct. Potassium-sparing diuretics must be avoided in patients with renal failure because they may cause life-threatening hyperkalemia. PF = peritubular interstitial fluid; TL = tubular lumen. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 7 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD DIURETICS AND POTASSIUM-SPARING AGENTS DAILY DOSE (mg) AGENT DURATION OF ACTION (hr) Thiazides Bendroflumethiazide (Naturetin) 01.25–5.0 >18 Benzthiazide (Aquatag, Exna) 12.5–50 12–18 Chlorothiazide (Diuril) 125–500 6–12 Cyclothiazide (Anhydron) 0.125–1 18–24 (Esidrix, 6.25–50 12–18 Hydroflumethiazide (Saluron) 12.5–50 18–24 Methyclothiazide (Enduron) 2.5–5.0 >24 Polythiazide (Renese) 1–4 24–48 Trichlormethiazide (Metahydrin, Naqua) 1–4 >24 Chlorthalidone (Hygroton) 12.5–50 24–72 Indapamide (Lozol) 1.25–2.5 24 Metolazone (Mykrox, Zaroxolyn) 0.5–10 24 Quinethazone (Hydromox) 25–100 18–24 Bumetanide (Bumex) 0.5–5 4–6 Ethacrynic acid (Edecrin) 25–100 12 Furosemide (Lasix) 40–480 4–6 Torsemide (Demadex) 5–40 12 Amiloride (Midamor) 5–10 24 Spironolactone (Aldactone) 25–100 8–12 Triamterene (Dyrenium) 50–100 12 Hydrochlorothiazide HydroDIURIL, Oretic) Related Sulfonamide Compounds Loop Diuretics Potassium-Sparing Agents From Kaplan NM: Clinical Hypertension. 7th ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1998, p 190. 8 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Hypokalemia. The degree of potassium wastage and hypokalemia is directly related to the dose of diuretic; serum potassium level falls an average of 0.7 mmol/liter with 50 mg of hydrochlorothiazide 0.4 with 25, and little if any with 12.5. Hypokalemia due to high doses of diuretic may precipitate potentially hazardous ventricular ectopic activity and increase the risk of primary cardiac arrest, even in patients not known to be susceptible because of concomitant digitalis therapy or myocardial irritability. Most patients are unaware of mild diuretic-induced hypokalemia, although it may contribute to leg cramps, polyuria, and muscle weakness, but subtle interference with antihypertensive therapy may accompany even mild hypokalemia, and correction of hypokalemia may result in a reduction in blood pressure. Prevention of hypokalemia is preferable to correction of potassium deficiency. The following maneuvers should help prevent diuretic-induced hypokalemia: Use the smallest dose of diuretic needed. Use a moderately long-acting (12- to 18-hour) diuretic, such as hydrocholorothiazide, because longer-acting drugs (e.g., chlorthalidone) may increase potassium loss. Restrict sodium intake to less than 100 mmol/day (i.e., 2.4 g sodium). Increase dietary potassium intake. Restrict concomitant use of laxatives. Use a combination of a thiazide with a potassium-sparing agent except in patients with renal insufficiency or in association with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II–receptor blocker. Concomitant use of a beta blocker or an ACE inhibitor diminishes potassium loss by blunting the diuretic-induced rise in renin-aldosterone. HYPERLIPIDEMIA. Serum cholesterol levels often rise after diuretic therapy, but after 1 year, no adverse effects were noted in those who responded to smaller doses. HYPERGLYCEMIA AND INSULIN RESISTANCE. High doses of diuretics may impair glucose tolerance and precipitate diabetes mellitus, probably because they increase insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. The manner by which diuretics increase insulin resistance is uncertain, but in view of the many potential pressor actions of hyperinsulinemia, this could be a significant problem. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 9 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD ADRENERGIC INHIBITORS A number of drugs that inhibit the adrenergic nervous system are available, including some that act centrally on vasomotor center activity, peripherally on neuronal catecholamine discharge, or by blocking alpha- and/or beta-adrenergic receptors ADRENERGIC INHIBITORS ADRENERGIC INHIBITORS USED IN TREATMENT OF HYPERTENSION Peripheral Neuronal Inhibitors Reserpine Guanethidine (Ismelin) Guanadrel (Hylorel) Bethanidine (Tenathan) Central Adrenergic Inhibitors Methyldopa (Aldomet) Clonidine (Catapres) Guanabenz (Wytensin) Guanfacine (Tenex) Alpha-Receptor Blockers Alpha1 and alpha2 receptor Phenoxybenzamine (Dibenzyline) Phentolamine (Regitine) Alpha1 receptor Doxazosin (Cardura) Prazosin (Minipress) Terazosin (Hytrin) Beta-Receptor Blocker Acebutolol (Sectral) Atenolol (Tenormin) Betaxolol (Kerlone) Bisoprolol (Zebeta) Carteolol (Cartrol) Metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol) Nadolol (Corgard) Penbutolol (Levatol) Pindolol (Visken) Propranolol (Inderal) Timolol (Blocadren) Alpha- and Beta-Receptor Blocker Labetalol (Normodyne, Trandate) Carvedilol (Dilatrend) When the nerve is stimulated, norepinephrine, which is synthesized intraneuronally and stored in granules, is released into the synaptic cleft. It binds to postsynaptic alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors and thereby initiates various intracellular processes. In vascular smooth muscle, alpha stimulation causes constriction and beta stimulation causes relaxation. In the central vasomotor centers, sympathetic outflow is inhibited by alpha stimulation; the effect of central beta stimulation is unknown. An important aspect of sympathetic activity involves the feedback of norepinephrine to alphaand beta-adrenergic receptors located on the neuronal surface, i.e., presynaptic receptors. Presynaptic alpha-adrenergic receptor activation inhibits release, whereas presynaptic beta activation stimulates further norepinephrine release. The presynaptic receptors probably has a role in the action of some of the drugs to be discussed Simplified schematic view of the adrenergic nerve ending showing that norepinephrine (NE) is released from its storage granules when the nerve is stimulated and enters the synaptic cleft to bind to alpha 1 and beta receptors on the effector cell (postsynaptic). In addition, a short feedback loop exists, in which NE 10 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD binds to alpha2 and beta receptors on the neuron (presynaptic), to inhibit or to stimulate further release, respectively. Drugs That Act Within the Neuron Reserpine, guanethidine, and related compounds act differently to inhibit the release of norepinephrine from peripheral adrenergic neurons. RESERPINE. 1. Reserpine, the most active and widely used of the derivatives of the rauwolfia alkaloids, depletes the postganglionic adrenergic neurons of norepinephrine by inhibiting its uptake into storage vesicles, exposing it to degradation by cytoplasmic monoamine oxidase. 2. The peripheral effect is predominant, although the drug enters the brain and depletes central catecholamine stores as well. This probably accounts for the sedation and depression accompanying reserpine use. 3. The drug has certain advantages: only one dose a day is needed; in combination with a diuretic, the antihypertensive effect is significant, greater than that noted with nitrendipine in one comparative study; little postural hypotension is noted; and many patients experience no side effects. 4. The drug has a relatively flat dose-response curve, so that a dose of only 0.05 mg/day gives almost as much antihypertensive effect as 0.125 or 0.25 mg/day but fewer side effects. 5. Although it remains popular in some places and is recommended as an inexpensive choice where resources are limited, reserpine has progressively declined in use because it has no commercial sponsor. GUANETHIDINE. 1. This agent acts by inhibiting the release of norepinephrine from the adrenergic neurons, perhaps by a local anesthetic-like effect on the neuronal membrane. In order to act, the drug must be transported actively into the nerve through an amine pump. 2. Their low lipid solubility prevents guanidine compounds from entering the brain, so that sedation, depression, and other side effects involving the central nervous system do not occur. 3. The initial predominant hemodynamic effect is decreased cardiac output: after continued use, peripheral resistance declines. 4. Blood pressure is reduced further when the patient is upright, owing to gravitational pooling of blood in the legs, because compensatory sympathetic nervous system– mediated vasoconstriction is blocked. This results in the most common side effect, postural hypotension. 5. Unlike reserpine, guanethidine has a steep dose-response curve, so that it can be successfully used in treating hypertension of any degree in daily doses of 10 to 300 mg. 6. Like reserpine, it has a long biological half-life and may be given once daily. 7. Guanethidine has been relegated mainly to the treatment of severe hypertension unresponsive to all other agents. Drugs That Act on Receptors Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 11 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Predominantly Central Alpha Agonists Until the mid-1980's, methyldopa was the most widely used of the adrenergic receptor blockers, but its use has declined as beta blockers and other drugs have become more popular. In addition, three other drugs—clonidine, guanabenz, and guanfacine, which act similarly to methyldopa but have fewer serious side effects—have become available. METHYLDOPA. 1. The primary site of action of methyldopa is within the central nervous system, where alpha-methylnorepinephrine, derived from methyldopa, is released from adrenergic neurons and stimulates central alpha-adrenergic receptors, reducing the sympathetic outflow from the central nervous system. 2. The blood pressure mainly falls as a result of a decrease in peripheral resistance with little effect on cardiac output. 3. Renal blood flow is well maintained, and significant postural hypotension is unusual. 4. The drug has been used in hypertensive patients with renal failure or cerebrovascular disease and remains the most commonly used agent for pregnancy-induced hypertension. 5. Methyldopa need be given no more than twice daily, in doses ranging from 250 to 1000 mg/day. 6. Side effects include some that are common to centrally acting drugs that reduce sympathetic outflow: sedation, dry mouth, impotence, and galactorrhea. However, methyldopa causes some unique side effects that are probably of an autoimmune nature, because a positive antinuclear antibody test result occurs in about 10 percent of patients who take the drug, and red cell autoantibodies occur in about 20 percent. Clinically apparent hemolytic anemia is rare, probably because methyldopa also impairs reticuloendothelial function so that antibody-sensitized cells are not removed from the circulation and hemolyzed. Inflammatory disorders in various organs have been reported, most commonly involving the liver (with diffuse parenchymal injury similar to viral hepatitis). CLONIDINE. 1. Although of different structure, clonidine shares many features with methyldopa. It probably acts at the same central sites, has similar antihypertensive efficacy, and causes many of the same bothersome but less serious side effects (e.g., sedation, dry mouth). It does not, however, induce the autoimmune and inflammatory side effects. 2. As an alpha-adrenergic receptor agonist, the drug also acts on presynaptic alpha receptors and inhibits norepinephrine release, and plasma catecholamine levels fall. 3. The drug has a fairly short biological half-life, so that when it is discontinued, the inhibition of norepinephrine release disappears within about 12 to 18 hours, and plasma catecholamine levels rise. This is probably responsible for the rapid rebound of the blood pressure to pretreatment levels and the occasional appearance of withdrawal symptoms, including tachycardia, restlessness, and sweating. If the rebound requires treatment, clonidine may be reintroduced or alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonists given. 4. Clonidine is available in a transdermal preparation, which may provide smoother blood pressure control for as long as 7 days with fewer side effects. However, bothersome skin rashes preclude its use in perhaps one-fourth of patients. 12 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Alpha1-adrenoceptor blocking agents. Alpha1 blockers (doxazosin, prazosin, terazosin) lower blood pressure by preventing catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction. In this illustration, norepinephrine released from the sympathetic nerve ending is depicted as circles, and the alpha 1-adrenergic blocking agent as an oval. The competitive action is confined to the vascular smooth muscle cell. These agents selectively block postsynaptic alpha1 adrenoceptors. Catecholamines can still activate presynaptic alpha 2 receptors and thus exert an inhibitory action on norepinephrine release by the sympathetic nerve terminal. This probably accounts for the lack of reflex heart rate acceleration during alpha1-adrenoceptor blockade. Alpha1 blockers induce dilation of both arteries and veins. The effect on the capacitive system accounts for the prominent fall in postural blood pressure that occurs in some patients; this effect often limits the utility of these agents. Alpha 1 blockers are effective in reducing the symptoms of benign prostatic hypertrophy, which makes them an attractive choice in hypertensive elderly men with that disorder. Alpha-Adrenergic Receptor Antagonists Before 1977, the only alpha blockers used to treat hypertension were phenoxybenzamine (Dibenzyline) and phentolamine (Regitine). These drugs are effective in acutely lowering blood pressure, but their effects are offset by an accompanying increase in cardiac output, and side effects are frequent and bothersome. Their limited efficacy may reflect their blockade of presynaptic alpha-adrenergic receptors, which interferes with the feedback inhibition of norepinephrine release. Increased catecholamine release would then blunt the action of postsynaptic alpha-adrenergic receptor blockade. Their use has largely been limited to the treatment of patients with pheochromocytomas. PRAZOSIN. 1. This was the first of a group of selective antagonists of the postsynaptic alpha1 receptors. 2. By blocking alpha-mediated vasoconstriction, prazosin induces a decline in peripheral resistance with both venous and arteriolar dilation. 3. Because the presynaptic alpha-adrenergic receptor is left unblocked, the feedback loop for the inhibition of norepinephrine release is intact, an action that is also certainly responsible for the greater antihypertensive effect of the drug and the absence of concomitant tachycardia, tolerance, and renin release. 4. Inhibition of norepinephrine release may also account for the propensity toward greater first-dose reductions in blood pressure. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 13 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Beta-Adrenergic Receptor Antagonists In the 1980's, beta-adrenergic receptor blockers became the most popular form of antihypertensive therapy after diuretics. For the majority of patients, beta-blockers are usually easy to take, because somnolence, dry mouth, and impotence are seldom encountered. Because beta-blockers have been found to reduce mortality if taken either before or after acute myocardial infarction (i.e., secondary prevention), it was assumed that they might offer special protection against initial coronary events, i.e., primary prevention. Classification of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers based on cardioselectivity and intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (ISA). Those not approved for use in the United States are in italics. (From Kaplan NM: Clinical Hypertension. 7th ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1998, p 206.) Clinical Effects. 1. Even in small doses, beta-blockers begin to lower the blood pressure within a few hours. 2. Although progressively higher doses have usually been given, careful study has shown a near-maximal effect from smaller doses. 3. The degree of blood pressure reduction is at least comparable to that noted with other antihypertensive drugs. 4. Beta blockers may be particularly well suited for younger and middle-aged hypertensive patients, especially nonblacks, and for patients with myocardial ischemia and high levels of stress. 5. Because the hemodynamic responses to stress are reduced, however, they may interfere with athletic performance. SPECIAL USES FOR BETA BLOCKERS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 14 COEXISTING ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE. COEXISTING HEART FAILURE. PATIENTS WITH HYPERKINETIC HYPERTENSION. PATIENTS WITH MARKED ANXIETY. PERIOPERATIVE STRESS. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD SIDE EFFECTS. Most of the side effects of beta blockers relate to their major pharmacological action, the blockade of beta-adrenergic receptors. Certain concomitant problems may worsen when betaadrenergic receptors are blocked, including peripheral vascular disease and bronchospasm. 1. The most common side effect is fatigue, which is probably a consequence of decreased cardiac output and the decreased cerebral blood flow that may accompany successful lowering of the blood pressure by any drug. 2. More direct effects on the central nervous system—insomnia, nightmares, and hallucinations—occur in some patients. 3. An association with depression appears to be accounted for by various confounding variables. 4. Diabetic patients may have additional problems with beta blockers, more so with nonselective ones. The responses to hypoglycemia, both the symptoms and the counterregulatory hormonal changes that raise blood glucose levels, are partially dependent on sympathetic nervous activity. Diabetic patients who are susceptible to hypoglycemia may not be aware of the usual warning signals and may not rebound as quickly. The majority of noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients can take these drugs without difficulty, although their diabetes may be exacerbated, probably from beta blocker interference with insulin sensitivity. 5. When a beta blocker is discontinued, angina pectoris and myocardial infarction may occur. Because patients with hypertension are more susceptible to coronary disease, they should be weaned gradually and given appropriate coronary vasodilator therapy. 6. Perturbations of lipoprotein metabolism accompany the use of beta blockers. Nonselective agents cause greater rises in triglycerides and reductions in cardioprotective high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels, whereas ISA agents cause less or no effect and some agents such as celiprolol may raise high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. 7. Caution is advised in the use of beta blockers in patients suspected of harboring a pheochromocytoma, because unopposed alpha-adrenergic agonist action may precipitate a serious hypertensive crisis if this disease is present. 8. The use of beta blockers during pregnancy has been clouded by scattered case reports of various fetal problems. Moreover, prospective studies have found that the use of beta blockers during pregnancy may lead to fetal growth retardation General overview of beta blockers in hypertension: 1. Beta blockers are specifically recommended for hypertensive patients with concomitant coronary disease, particularly after a myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or tachyarrhythmias. 2. If a beta blocker is chosen, those agents that are more cardioselective and lipid insoluble offer the likelihood of fewer perturbations of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and greater patient adherence to therapy; only one dose a day is needed, and side effects probably are minimized. 3. In patients with heart failure, the initial dose should be very small (e.g., metoprolol 12.5 mg twice daily) and gradually increased to the maintenance dose (100 to 200 mg twice daily). Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 15 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Alpha- and Beta-Adrenergic Receptor Antagonists 1. The combination of an alpha and a beta-blocker in a single molecule is available in the forms of labetalol and carvedilol, the latter agent approved for treatment of heart failure as well. 2. The fall in pressure mainly results from a decrease in peripheral resistance, with little or no decline in cardiac output. 3. The most bothersome side effects are related to postural hypotension; the most serious side effect is hepatotoxicity. 4. Intravenous labetalol is used to treat hypertensive emergencies. VASODILATORS Direct Vasodilators Hydralazine is the most widely used agent of this type. Minoxidil is more potent but is usually reserved for patients with severe, refractory hypertension associated with renal failure. Nitroprusside and nitroglycerin are given intravenously for hypertensive crises. HYDRALAZINE. 1. From the early 1970's, hydralazine, in combination with a diuretic and a beta blocker, was used frequently to treat severe hypertension. 2. The drug acts directly to relax the smooth muscle in precapillary resistance vessels, with little or no effect on postcapillary venous capacitance vessels. 3. As a result, blood pressure falls by a reduction in peripheral resistance, but in the process a number of compensatory processes, which are activated by the arterial baroreceptor arc, blunt the decrease in pressure and cause side effects. 4. With concomitant use of a diuretic to overcome the tendency for fluid retention and an adrenergic inhibitor to prevent the reflex increase in sympathetic activity and rise in renin, the vasodilator is more effective and causes few, if any, side effects. 5. Without the protection conferred by concomitant use of an adrenergic blocker, numerous side effects (tachycardia, flushing, headache, and precipitation of angina) may occur. 6. The drug need be given only twice a day. Its daily dose should be kept below 400 mg to prevent the lupus-like syndrome that appears in 10 to 20 percent of patients who receive more. This reaction, although uncomfortable to the patient, is almost always reversible. The reaction is uncommon with daily doses of 200 mg or less. MINOXIDIL. 1. This drug vasodilates by opening potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. 2. Its hemodynamic effects are similar to those of hydralazine, but minoxidil is even more effective and may be used once a day. 3. It is particularly useful in patients with severe hypertension and renal failure. 4. Even more than with hydralazine, diuretics and adrenergic receptor blockers must be used with minoxidil to prevent the reflex increase in cardiac output and fluid retention. 5. Pericardial effusions have appeared in about 3% of those given minoxidil, in some without renal or cardiac failure. The drug also causes hair to grow profusely, and the facial hirsutism precludes use of the drug in most women. 16 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Calcium Antagonists 1. These drugs have become the most popular class of agents used in the treatment of hypertension. 2. Dihydropyridines have the greatest peripheral vasodilatory action, with little effect on cardiac automaticity, conduction, or contractility. 3. However, comparative trials have shown that verapamil and diltiazem, which do affect these properties, are also effective antihypertensives, and they may cause fewer side effects related to vasodilation, such as flushing and ankle edema. PHARMACOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF CALCIUM ANTAGONISTS DILTIAZEM VERAPAMIL DIHYDROPYRIDINES Heart rate – Myocardial contractility – Nodal conduction – Peripheral vasodilation Indicates decrease; , increase; –, no change. 4. Calcium antagonists are effective in hypertensive patients of all ages and races and in hypertensive diabetics. 5. Calcium antagonists may cause at least an initial natriuresis, probably by producing renal vasodilation, which may obviate the need for concurrent diuretic therapy. Renin-Angiotensin Inhibitors Activity of the renin-angiotensin system may be inhibited in four ways, three of which can be applied clinically: The first, use of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers to inhibit the release of renin, was discussed earlier. The second, direct inhibition of renin activity by specific renin inhibitors, is being investigated. The third, inhibition of the enzyme that converts the inactive decapeptide angiotensin I to the active octapeptide angiotensin II, is being widely used with orally effective ACE inhibitors. The fourth approach to inhibiting the renin-angiotensin system, blockade of angiotensin's actions by a competitive receptor blocker, is now the basis for the fastest growing class of antihypertensive agents. The AII receptor blockers (ARBs) may offer additional benefits, but their immediate advantage is the absence of cough that often accompanies ACE inhibitors, as well as less angioedema. *In the absence of outcome data, both JNC-6 and WHO-ISH guidelines recommend their use only if an ACE inhibitor cannot be tolerated. The ARBs are considered after the ACE inhibitors. MECHANISM OF ACTION. The first of these ACE inhibitors, captopril, was synthesized as a specific inhibitor of the converting enzyme that, in the classical pathway, breaks the peptidyldipeptide bond in angiotensin I, preventing the enzyme from attaching to and splitting the angiotensin I structure. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 17 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Because angiotensin II cannot be formed and angiotensin I is inactive, the ACE inhibitor paralyzes the classical renin-angiotensin system, thereby removing the effects of most endogenous angiotensin II as both a vasoconstrictor and a stimulant to aldosterone synthesis. Overall scheme of the renin-angiotensin mechanism indicating the site of action of angiotensin II type I receptor antagonist. The four sites of action of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system. J-G = Juxtaglomerular apparatus; CE = converting enzyme. 18 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Dual role of ACE inhibitors, both in preventing and treating cardiovascular disease. Note multiple sites of action in both primary and secondary prevention. ACE inhibitors have an indirect effect in primary prevention by lessening hypertension and by decreasing left ventricular hypertrophy. They protect the blood vessels indirectly by an antihypertensive effect and directly inhibit carotid atherogenesis and thrombogenesis. Given at the start of myocardial infarction, they improve mortality in high-risk patients. By an antiarrhythmic effect, they may act to prevent postinfarct sudden death. By lessening wall stress, they beneficially improve postinfarct remodeling and decrease the incidence of left ventricular failure. LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy. Interestingly, with long-term use of ACE inhibitors, the plasma angiotensin II levels actually return to previous level while the blood pressure remains lowered; this suggests that the antihypertensive effect may involve other mechanisms: o Because the same enzyme that converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II is also responsible for inactivation of the vasodilating hormone bradykinin, by inhibiting the breakdown of bradykinin, ACE inhibitors increase the concentration of a vasodilating hormone while they decrease the concentration of a vasoconstrictor hormone. o The increased plasma kinin levels may contribute to the vasodilation and improvement in insulin sensitivity observed with ACE inhibitors, but they are also responsible for the most common and bothersome side effect of their use, a dry, hacking cough. o ACE inhibitors may also vasodilate by increasing levels of vasodilatory prostaglandins and decreasing levels of vasoconstricting endothelins. Regardless of their mechanism of action, ACE inhibitors lower blood pressure mainly by reducing peripheral resistance with little, if any, effect on heart rate, cardiac output, or body fluid volumes, likely reflecting preservation of baroreceptor reflexes. Their vasodilating effect may also involve restoration of endothelium-dependent relaxation by nitric oxide. As a consequence, resistance arteries become less thickened and more responsive. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 19 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD ACE inhibitors have dual vasodilatory actions, chiefly on the renin-angiotensin system with ancillary effects on the breakdown of bradykinin. The result of the former action is the inhibition of the vasoconstrictory systems and the result of the latter is the formation of vasodilatory nitric oxide and prostacyclin. These effects of bradykinin may protect the endothelium. A-II = angiotensin II; AT1 = angiotensin II subtype 1. CLINICAL USE: 1. In patients with uncomplicated primary hypertension, ACE inhibitors provide antihypertensive effects that are equal to those with other classes, but they are less effective in blacks, perhaps because blacks tend to have lower renin levels. 2. They are equally effective in elderly and younger hypertensive patients. 3. The WHO-ISH guidelines include ACE inhibitors as a choice for initial therapy. 4. In view of the impressive reduction in morbidity and mortality with ramipril in the HOPE trial of high-risk patients, the use of ACE inhibitors will almost certainly increase. 5. The initial dose of ACE inhibitor may precipitate a rather dramatic but transient fall in blood pressure that likely reflects a higher level of renin-angiotensin and that could be a harbinger of the presence of renovascular hypertension (simple diagnostic test for the disease). 6. The removal of the high levels of angiotensin II that they produce may deprive the stenotic kidney of the hormonal drive to its blood flow, thereby causing a marked decline in renal perfusion so that patients with solitary kidneys or bilateral disease may develop acute and sometimes persistent renal failure. 7. Patients with intraglomerular hypertension, specifically those with diabetic nephropathy or reduced renal functional mass due to other forms of renal parenchymal disease, may benefit especially from the reduction in efferent arteriolar resistance that follows reduction in angiotensin II. 8. ACE inhibitors are the best tolerated antihypertensive agents (along with ARBs), so their use will continue to grow. 20 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD SIDE EFFECTS. 1. Cough (10 percent of women and about half as many men). If a cough appears in a patient who needs an ACE inhibitor, an ARB should be substituted ! 2. Rash. 3. Loss of taste. 4. Leukopenia (neutropenia). 5. Hyperkalemia. 6. Angioneurotic edema. ANGIOTENSIN II RECEPTOR BLOCKERS (ARBs) CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OF AVAILABLE ANGIOTENSIN II RECEPTOR BLOCKERS ACTIVE METABOLITE FOOD EFFECT HALF-LIFE (hr) Prodrug No 9–10 Irbesartan (Avapro) No No 11–15 Losartan (Cozaar) Yes Modest 2–4 Telmisartan (Micardis) No No 18–24 Valsartan (Diovan) No Moderate 6–8 COMPOUND Candesartan (Atacand) Schematic representation of a possible mechanism of action of the AT 1 receptor antagonist. Blockade of the AT1 receptor is accompanied by increased circulating angiotensin II (Ang II) plasma levels, which stimulate the unblocked AT2 receptor. This induces a rise in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) formation. L NAME = NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; NOS = nitric oxide synthase; HOE = code number of Hoechst 140, at present also known as I cantilant. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 21 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Other Vasodilators Various other forms of antihypertensive therapy are under investigation: endothelin receptor antagonists agents that inhibit both the ACE and neutral endopeptidase, thereby increasing atrial natriuretic hormone. The distant future may see the application of gene therapy. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THERAPY HYPERTENSION IN THE ELDERLY. A few elderly persons may have high blood pressure as measured by the sphygmomanometer but may have less or no hypertension when direct intraarterial readings are made, i.e., pseudohypertension due to rigid arteries that do not collapse under the cuff. 22 If either the systolic pressure alone or both systolic and diastolic levels are elevated, careful lowering of blood pressure with either diuretics or dihydropyridine calcium antagonists has been unequivocally documented to reduce cardiovascular morbidity in older hypertensive patients extending to those older than 80 years. In view of the reduced effectiveness of the baroceptor reflex and the failure of peripheral resistance to rise appropriately with standing, drugs with a propensity to cause postural Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD hypotension should be avoided, and all drugs should be given in slowly increasing doses to prevent excessive lowering of the pressure. For those who start with systolic pressures exceeding 160 mm Hg, the goal of therapy should be a level around 140 mm Hg with little concern about further reductions in already low diastolic levels. FACTORS THAT MIGHT CONTRIBUTE TO INCREASED RISK OF PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT OF HYPERTENSION IN THE ELDERLY POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS FACTORS Diminished baroreceptor activity Orthostatic hypotension Decreased intravascular volume Orthostatic hypotension, dehydration Sensitivity to hypokalemia Arrhythmia, muscle weakness Decreased renal and hepatic function Drug accumulation Polypharmacy Drug interaction Central nervous system changes Depression, confusion PATIENTS WITH HYPERTENSION AND DIABETES. Most diabetic hypertensive patients need two or more antihypertensive drugs to bring their pressure to below 130/85 mm Hg, which is likely the highest level that should be tolerated. An ACE inhibitor should be included if proteinuria is present. A diuretic and a beta-blocker are appropriate, and a long-acting dihydropyridine will likely be required. HYPERTENSIVE PATIENTS WITH IMPOTENCE. Erectile dysfunction is common in hypertensive patients, even more so in those who are also diabetic. The problem may be exacerbated by diuretic therapy, even in appropriately low doses. Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 23 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD Fortunately, sildenafil (Viagra) usually returns erectile ability, but caution is advised with antihypertensive drugs.The potential for hypotension, well recognized with concomitant nitrate therapy, may also appear with other vasodilators, although to a lesser degree. HYPERTENSION WITH CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE. Lowering the blood pressure may, by itself, relieve the heart failure. Chronic unloading has been most efficiently accomplished with ACE inhibitors, and beta blockers have been shown to further reduce morbidity and mortality in ACE inhibitor–treated patients in heart failure. Caution is needed for those elderly hypertensive patients with diastolic dysfunction related to marked left ventricular hypertrophy, because unloaders may worsen their status, whereas beta blockers or calcium antagonists may be beneficial. All antihypertensive drugs except direct vasodilators have been shown to regress left ventricular hypertrophy and regression may continue for as long as 5 years of treatment. (Jennings G, Wong J: Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension: Changing patterns with successive meta-analyses. J Hypertens 16:S29, 1998) HYPERTENSION WITH ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE. The coexistence of ischemic heart disease makes antihypertensive therapy even more essential, because relief of the hypertension may ameliorate the coronary disease. Beta blockers and calcium antagonists are particularly useful if angina or arrhythmias are present. 24 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD THERAPY FOR HYPERTENSIVE CRISES When DBP exceeds 140 mm Hg, rapidly progressive damage to the arterial vasculature is demonstrable experimentally, and a surge of cerebral blood flow may rapidly lead to encephalopathy If such high pressures persist or if there are any signs of encephalopathy, the pressures should be lowered using parenteral agents in those patients considered to be in immediate danger or with oral agents in those who are alert and in no other acute distress. PARENTERAL DRUGS FOR TREATMENT OF HYPERTENSIVE EMERGENCY (IN ORDER OF RAPIDITY OF ACTION) DRUG ONSET ACTION DOSAGE OF ADVERSE EFFECTS Vasodilators Nitroprusside (Nipride, 0.25–10 Nitropress) infusion mg/kg/min as IV Instantaneous Nausea, vomiting, muscle twitching, sweating, thiocyanate intoxication Nitroglycerin 5–100 mg/min as IV infusion 2–5 min Tachycardia, flushing, headache, vomiting, methemoglobinemia Nicardipine (Cardene) 5–15 mg/hr IV 5–10 min Tachycardia, flushing, phlebitis Hydralazine (Apresoline) 10–20 10–50 mg IM Enalapril (Vasotec IV) 1.25–5 mg q 6 hr 15 min Precipitous fall in blood pressure in high renin states; response variable Fenoldopam (Corlopam) 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/min <5 min Tachycardia, headache, nausea, flushing Phentolamine (Regitine) 5–15 mg IV 1–2 min Tachycardia, flushing Esmolol (Brevibloc) 500 mg/kg/min for 4 min, then 1–2 min 150–300 mg/kg/min IV mg IV 10–20 20–30 min headache, local min Tachycardia, flushing, headache, vomiting, aggravation of angina Adrenergic inhibitors Labetalol Trandate) (Normodyne, 20–80 mg IV bolus every 10 min 5–10 min 2 mg/min IV infusion Hypotension Vomiting, scalp tingling, burning in throat, postural hypotension, dizziness, nausea 1. If diastolic pressure exceeds 140 mm Hg and the patient has any complications, such as an aortic dissection, a constant infusion of nitroprusside is most effective and almost always lowers the pressure to the desired level. Constant monitoring with an intraarterial line is mandatory because a slightly excessive dose may lower the pressure abruptly to Braunwald 6th ed. 2001 25 Conf. dr. Laurenţiu Şorodoc MD, PhD levels that induce shock. The potency and rapidity of action of nitroprusside have made it the treatment of choice for life-threatening hypertension. However, nitroprusside acts as a venous and arteriolar dilator, so that venous return and cardiac output are lowered and intracranial pressures may increase. 2. Other parenteral agents are being more widely used. These include labetalol and the calcium antagonist nicardipine. 3. With any of these agents, intravenous furosemide is often needed to lower the blood pressure further and prevent retention of salt and water. Diuretics should not be given if volume depletion is initially present. For patients in less immediate danger, oral therapy may be used. Almost every drug has been used and most will, with repeated doses, reduce high pressures. The prior preference for liquid nifedipine by mouth or sublingually has been deflated because of occasional ischemic complications from too rapid reduction in blood pressure. Oral doses of other short-acting formulations may be used, including furosemide, propranolol, captopril, or felodipine. 26 Braunwald 6th ed. 2001