* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download signals - Biologie ENS

Citric acid cycle wikipedia , lookup

Vectors in gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Polyclonal B cell response wikipedia , lookup

Biochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Paracrine signalling wikipedia , lookup

Biochemical cascade wikipedia , lookup

Evolution of metal ions in biological systems wikipedia , lookup

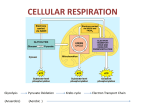

5 Cell Signaling and Communication 7.1 What Are Signals, and How Do Cells Respond to Them? All cells process information from the environment. The information can be a chemical, or a physical stimulus such as light. Signals can come from outside the organism, or from neighboring cells. Not all cells can respond to all signals ! A cell must have a specific receptor that can detect a specific signal 7.1 What Are Signals, and How Do Cells Respond to Them? In a large multicellular organism, signals reach target cells by diffusion or by circulation in the blood. Autocrine signals affect the cells that made them. Paracrine signals affect nearby cells. Hormones travel to distant cells, usually via the circulatory system. Figure 7.1 Chemical Signaling Systems autocrine paracrine Hormone 7.1 What Are Signals, and How Do Cells Respond to Them? To respond to a signal, a cell must have a specific receptor that can detect it. A signal transduction pathway is the sequence of molecular events and chemical reactions that lead to a cell’s response to a signal. => Involves a signal, a receptor and a response Figure 7.2 A Signal signal Transduction Pathway receptor response Figure 7.5 Two Locations for Receptors Figure 7.3 A Model Signal Transduction Pathway (Part 2) The solute concentration around Escherichia coli in a mammalian intestine changes often. The bacterium must respond quickly to this environmental signal. Figure 7.3 A Model Signal Transduction Pathway (Part 2) The solute concentration around E. coli in a mammalian intestine changes often. The bacterium must respond quickly to this environmental signal. Figure 7.3 A Model Signal Transduction Pathway (Part 2) The solute concentration around E. coli in a mammalian intestine changes often. The bacterium must respond quickly to this environmental signal. 7.1 What Are Signals, and How Do Cells Respond to Them? Conformation of OmpR (the responder) changes. Signal from outside has now been transduced to a protein inside the cell. The effect: Phosphorylated OmpR binds to DNA to increase the expression of the protein OmpC. Figure 7.3 A Model Signal Transduction Pathway (Part 2) The solute concentration around E. coli in a mammalian intestine changes often. The bacterium must respond quickly to this environmental signal. 7.1 What Are Signals, and How Do Cells Respond to Them? The signal has been amplified: One EnvZ molecule can change the conformation of many OmpR molecules. The OmpC protein is inserted in the outer membrane where it blocks pores and prevents solutes from entering. 7.1 What Are Signals, and How Do Cells Respond to Them? Summary of this signal transduction pathway: • The signal causes a receptor protein to change conformation • Conformation change gives it protein kinase activity • Phosphorylation alters function of a responder protein • The signal is amplified • A protein that binds to DNA is activated • Expression of one or more genes is turned on or off • Cell activity is altered Figure 7.9 A Cytoplasmic Receptor Cytoplasmic receptors bind ligands that can cross the plasma membrane. Binding to ligand causes receptor to change shape —allows it to enter nucleus, where it affects gene expression. Receptor may be bound to a chaperonin; binding to ligand releases the chaperonin. 7.5 How Do Cells Communicate Directly? Multicellular organisms have cell junctions that allow communication: • Gap junctions in animals Gap junctions: Channels between adjacent cells traversed by proteins forming a channel. Too small for proteins, but wide enough for signaling molecules. 5 Energy, Enzymes, and Metabolism 8.1 What Physical Principles Underlie Biological Energy Transformations? The transformation of energy is a hallmark of life. Energy is the capacity to do work, or the capacity for change. Energy transformations are linked to chemical transformations in cells. 8.1 What Physical Principles Underlie Biological Energy Transformations? Metabolism: Sum total of all chemical reactions in an organism. Anabolic reactions: Complex molecules are made from simple molecules; energy input is required. Catabolic reactions: Complex molecules are broken down to simpler ones and energy is released. Figure 8.5 ATP (Part 1) ATP is a nucleotide. 8.2 What Is the Role of ATP in Biochemical Energetics? ATP is a nucleotide. Hydrolysis of ATP yields free energy. ATP + H 2O → ADP + Pi + free energy Réaction exoénergétique Figure 8.5 ATP (Part 2) 8.2 What Is the Role of ATP in Biochemical Energetics? Bioluminescence is an endergonic reaction driven by ATP hydrolysis: luciferase luciferin + O2 + ATP ⎯⎯⎯ ⎯→ oxyluciferin + AMP + PPi + light 8.2 What Is the Role of ATP in Biochemical Energetics? The formation of ATP is endergonic: ADP + Pi + free energy → ATP + H 2O Formation and hydrolysis of ATP couples exergonic and endergonic reactions. Figure 8.6 Coupling of Reactions Exergonic and endergonic reactions are coupled. Figure 8.6 Coupling of Reactions Exergonic and endergonic reactions are coupled. 8.3 What Are Enzymes? Catalysts speed up the rate of a reaction. The catalyst is not altered by the reactions. Most biological catalysts are enzymes (proteins) that act as a framework in which reactions can take place. 8.3 What Are Enzymes? Biological catalysts (enzymes and ribozymes) are highly specific. Reactants are called substrates.Substrate molecules bind to the active site of the enzyme. The three-dimensional shape of the enzyme determines the specificity. 5 Pathways that Harvest Chemical Energy 9.1 How Does Glucose Oxidation Release Chemical Energy? Fuels: Molecules whose stored energy can be released for use. The most common fuel in organisms is glucose. Other molecules are first converted into glucose or other intermediate compounds. 9.1 How Does Glucose Oxidation Release Chemical Energy? • Three metabolic pathways are involved in harvesting the energy of glucose: • Glycolysis—glucose is converted to pyruvate • Cellular respiration—aerobic and converts pyruvate into H2O, CO2, and ATP • Fermentation—anaerobic and converts pyruvate into lactic acid or ethanol, CO2, and ATP Figure 9.1 Energy for Life 9.1 How Does Glucose Oxidation Release Chemical Energy? If O2 is present (aerobic) glycolysis is followed by three pathways of cellular respiration: • Pyruvate oxidation • Citric acid cycle (= Krebs cycle) • Electron transport chain If O2 is not present, pyruvate from glycolysis is metabolized by fermentation. Figure 9.4 Energy-Producing Metabolic Pathways Table 9.1 The five metabolic pathways occur in different parts of the cell. 9.2 What Are the Aerobic Pathways of Glucose Metabolism? Glycolysis takes place in the cytosol: • Converts glucose into pyruvate • Produces a small amount of energy • Generates no CO2 Results in: 2 molecules of pyruvate 2 molecules of ATP 10 steps (reactions) with 10 enzymes Figure 9.5 Glycolysis Converts Glucose into Pyruvate (Part 1) Glycolysis http://theses.ulaval.ca/archimede/fichiers/23727/23727_4.png 9.2 What Are the Aerobic Pathways of Glucose Metabolism? Pyruvate Oxidation: • Links glycolysis and the citric acid cycle; occurs in the mitochondrie • Pyruvate is oxidized to acetate and CO2 is released • Some energy is stored by combining acetate and Coenzyme A (CoA) to form acetyl CoA Figure 9.7 Pyruvate Oxidation and the Citric Acid Cycle (Part 1) Figure 9.7 Pyruvate Oxidation and the Citric Acid Cycle (Part 2) Figure 9.6 Changes in Free Energy During Glycolysis and the Citric Acid Cycle 9.2 What Are the Aerobic Pathways of Glucose Metabolism? The electron carriers that are reduced during the citric acid cycle must be reoxidized to take part in the cycle again. Fermentation—if no O2 is present Oxidative phosphorylation—O2 is present Figure 9.9 The Respiratory Chain and ATP Synthase Produce ATP by a Chemiosmotic Mechanism (Part 1) Figure 9.9 The Respiratory Chain and ATP Synthase Produce ATP by a Chemiosmotic Mechanism (Part 2) 9.3 How Does Oxidative Phosphorylation Form ATP? Oxidative phosphorylation: ATP is synthesized by reoxidation of electron carriers in the presence of O2. Two stages: • Electron transport • Transport protons across membrane Figure 9.13 Cellular Respiration Yields More Energy Than Fermentation Cellular respiration yields more energy than fermentation per glucose molecule. • Glycolysis plus fermentation = 2 ATP • Glycolysis plus cellular respiration = 32 ATP Figure 9.14 Relationships among the Major Metabolic Pathways of the Cell 9.1 How Does Glucose Oxidation Release Chemical Energy? Principles governing metabolic pathways: • Complex chemical transformations occur in a series of reactions • Each reaction is catalyzed by a specific enzyme • Metabolic pathways are similar in all organisms • In eukaryotes, metabolic pathways are compartmentalized in organelles • Each pathway is regulated by key enzymes 8.5 How Are Enzyme Activities Regulated? Metabolic pathways can be modeled using mathematical algorithms. This field is called systems biology. Figure 9.15 Regulation by Negative and Positive Feedback 5 The Cell Cycle and Cell Division 11.1 How Do Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Divide? The life cycle of an organism is linked to cell division. Unicellular organisms use cell division primarily for reproduction. In multicellular organisms, cell division is also important in growth and repair of tissues. 11.1 How Do Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Divide? Four events must occur for cell division: • Reproductive signal: To initiate cell division • Replication: Of DNA • Segregation: Distribution of the DNA into the two new cells • Cytokinesis: Separation of the two new cells 11.1 How Do Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Divide? In prokaryotes, binary fission results in two new cells. External factors such as nutrient concentration and environmental conditions are the reproductive signals that initiate cell division. For many bacteria, abundant food supplies speed up the division cycle. Figure 11.2 Prokaryotic Cell Division (Part 1) 11.1 How Do Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Divide? In eukaryotes, signals for cell division are related to the needs of the entire organism. • Growth factors: External chemical signals that stimulate these cells to divide • Platelet-derived growth factor: From platelets that initiate blood clotting, stimulates skin cells to divide and heal wounds. 11.1 How Do Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Divide? DNA replication usually occurs between cell divisions. Sister chromatids—newly replicated chromosomes are closely associated. (many chromosomes !) Mitosis separates them into two new nuclei, identical to the parent cell. Meiosis is nuclear division in cells involved in sexual reproduction. The cells resulting from meiosis are not identical to the parent cells. 11.2 How Is Eukaryotic Cell Division Controlled? The cell cycle: The period between cell divisions, divided into mitosis/ cytokinesis and interphase. Interphase: The cell nucleus is visible and cell functions including replication occur. Interphase begins after cytokinesis and ends when mitosis starts. 11.2 How Is Eukaryotic Cell Division Controlled? Interphase has three subphases: G1, S, and G2 • G1: Gap 1—between end of cytokinesis and onset of S phase; chromosomes are single, unreplicated structures • S phase: DNA replicates; one chromosome becomes two sister chromatids • G2: Gap 2—end of S phase, cell prepares for mitosis Figure 11.8 Chromosomes, Chromatids, and Chromatin 11.3 What Happens during Mitosis? After DNA replicates, its segregation occurs during mitosis. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%C3%89v%C3%A9nements_importants_en_mitose.svg 11.3 What Happens during Mitosis? Mitosis can be divided into phases: • Prophase • Prometaphase • Metaphase • Anaphase • Telophase 11.3 What Happens during Mitosis? Cytokinesis: Division of the cytoplasm differs in plant and animals. Mitosis ensures precise distribution of chromosomes The organelles are not necessarily equally distributed 11.4 What Role Does Cell Division Play in a Sexual Life Cycle? Somatic cells—body cells not specialized for reproduction. Each somatic cell contains homologous pairs of chromosomes with corresponding genes. Each parent contributes one homolog. 11.4 What Role Does Cell Division Play in a Sexual Life Cycle? Sexual reproduction: The offspring are not identical to the parents. It requires gametes created by meiosis; two parents each contribute one gamete to an offspring. Gametes—and offspring—differ genetically from each other and from the parents. 11.4 What Role Does Cell Division Play in a Sexual Life Cycle? Gametes contain only one set of chromosomes. • Haploid: Number of chromosomes = n • Fertilization: Two haploid gametes (female egg and male sperm) fuse to form a diploid zygote; chromosome number = 2n Sexual reproduction generates diversity among individual organisms. Figure 11.15 Fertilization and Meiosis Alternate in Sexual Reproduction (Part 3) 11.5 What Happens during Meiosis? Meiosis consists of two nuclear divisions but DNA is replicated only once. The function of meiosis is to: • Reduce the chromosome number from diploid to haploid • Ensure that each haploid has a complete set of chromosomes • Generate diversity among the products 11.5 What Happens during Meiosis? 11.5 What Happens during Meiosis? Differences between meiosis II and mitosis: • DNA does not replicate before meiosis II • In meiosis II the sister chromatids may not be identical because of crossing over Figure 11.21 Nondisjunction Leads to Aneuploidy 11.5 What Happens during Meiosis? In humans, if both chromosome 21 homologs go to the same pole and the resulting egg is fertilized, it will be trisomic for chromosome 21. This results in the condition known as Down syndrome. A fertilized egg that did not receive a copy of chromosome 21 will be monosomic, which is lethal. 11.6 In a Living Organism, How Do Cells Die? Cell death occurs in two ways: • Necrosis—cell is damaged or starved for oxygen or nutrients. The cell swells and bursts Cell contents are released to the extracellular environment and can cause inflammation 11.6 In a Living Organism, How Do Cells Die? • Apoptosis is genetically programmed cell death. Two possible reasons: Cell is no longer needed, e.g., the connective tissue between the fingers of a fetus Old cells may be prone to genetic damage that can lead to cancer; blood cells and epithelial cells die after days or weeks 11.7 How Does Unregulated Cell Division Lead to Cancer? Cancer cells differ from original cells in two ways: • Cancer cells lose control over cell division • They can migrate to other parts of the body 11.7 How Does Unregulated Cell Division Lead to Cancer? Normal cells divide in response to extracellular signals, like growth factors. Cancer cells don’t respond to these signals, instead growing almost continuously. A tumor is a large mass of cells. Benign tumors resemble the tissue they grow from, grow slowly, and remain localized. Malignant tumors do not resemble the tissue they grow from and may have irregular structures. 11.7 How Does Unregulated Cell Division Lead to Cancer? Oncogene proteins are positive regulators of cancer cells. Derived from normal regulators that are overactive or in excess, such as growth factors or their receptors. Example: An increased number of receptors for HER2 in breast tissue may result in rapid cell proliferation. 11.7 How Does Unregulated Cell Division Lead to Cancer? Tumor suppressors are negative regulators in both cancer and normal cells, but in cancer cells they are inactive. Proteins such as p21, p53, and RB that normally block the cell cycle are tumor suppressors but may be blocked by a virus, such as HPV. http://missinglink.ucsf.edu/lm/cell_cycle/oncogenes.html