* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Roman Empire (after 27 BC)

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Centuriate Assembly wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman dictator wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republican governors of Gaul wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

Roman Senate wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Late Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman emperor wikipedia , lookup

Roman consul wikipedia , lookup

Senatus consultum ultimum wikipedia , lookup

Elections in the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Executive magistrates of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Augustus wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

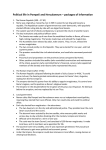

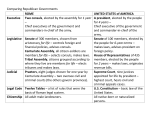

The Roman political system The Roman Republic (509 – 27 BC) Rome had been a monarchy since its earliest days, but in 509 its last king, Tarquin the Proud, was overthrown, and Rome became a republic. The Republican system of government was semi-democratic, with popularly elected officials ruling side-by side with an oligarchical Senate. The system was full of checks and balances, to prevent the return of another tyrant. The Senate The Senate advised the consuls. It was made up of men from the wealthiest families in Rome. There were about 600 Senators, all former high-ranking magistrates. They were appointed for life by the censors, who in turn were elected by the Assembly. Although the Senate’s decisions were not legally binding, usually they were followed by the magistrates. The Senate’s primary responsibility was foreign policy. The Assemblies The various Assemblies were elected by adult, male citizens of Rome. They, in turn, elected the various magistrates: consuls, praetors, quaestors, aediles, censors and tribunes. They also enacted legislation, presided over major criminal trials, declared war and peace, and made treaties with other states. The cursus hornorum The cursus honorum was the order of public office to held by aspiring politicians. It started with ten years of military service. Roman administrators would then progress to quaestor, aedile, praetor and finally consul. All of these positions gave the holder membership of the Senate, once their service was complete. Consuls The two consuls jointly administered the Roman Republic (in order to prevent the return of tyranny). They consuls had supreme power (called ‘imperium’) in both military and civil matters. They also had the power of veto (Latin for “I forbid it”), so both had to agree on a policy before it could be introduced. The consuls were elected for a term of one year. After serving their term, they could not be re-elected for another ten years. Praetors The praetors were the second most important officials in Rome. They controlled the civil administration, and could also command provincial armies. Like the consuls, they were appointed for a one year term. Between 6 and 8 were appointed each year. The minimum age was 39. 1 Aediles Aediles were responsible for water and food supplies, as well as the construction and maintenance of public buildings. They also organised public games. For aediles were elected each year. The minimum age was 36. Quaestors Quaestors assisted the consuls and the provincial governors with the financial affairs of Rome. Ten quaestors were elected each year. The minimum age was 30. Censors The censors conducted the census of Roman citizens. They had the power to appoint and purge members of the Senate. They were elected for a period of 18 months. Tribunes The ten tribunes were elected by the Assemblies to represent the poor. They could veto any decision of the Senate or a magistrate that affected the poor. Tribunes could present legislation to the Senate, and could arrest magistrates if they were in breach of the law. Provincial governors As Rome began to conquer other lands, governors were appointed to run these provinces. They governors were either former consuls (known as Proconsuls) or former praetors (Propraetors). They acted like mini-tyrants in their particular provinces, with power over the courts and the army. This became a major problem as the empire expanded, as powerful provincial governors were tempted to return home with their armies and take control of Rome. For this reason, no commander was allowed to enter Italy with his army. Two famous governors broke this rule: Sulla and Julius Caesar. Both became dictators for a time. Dictator In times of emergency, the Senate could appoint a dictator, to rule Rome with absolute power until the emergency passed. The position was abolished after Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC. The Roman Empire (after 27 BC) The collapse of the Republic By the middle of the 1st century BC, the Roman Empire had become so large that it was increasingly difficult for the government to administer it. Provincial governors became so powerful that they could use their wealth and their legions to subvert the political institutions of Rome. Julius Caesar fought a civil war against his rival Pompey the Great, whom he defeated. He then appointed himself dictator for life (49 BC), but was assassinated 2 by Brutus and Cassius in 44 BC. They, in turn, were in turn defeated by Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian, and his lieutenant Mark Antony in 42 BC. Octavian and Antony divided the empire between them, with Octavian based in the West, and Antony in the East. The two leaders eventually fell out, and fought each other for control. In 31 BC Octavian was victorious at the Battle of Actium. Over the next four years, he was granted extraordinary powers by the Senate so that, in effect, he became Rome’s first emperor. In the process, he changed his name to Caesar Augustus. The emperor The Roman Emperor was called the princeps, or first citizen. His power (imperium) derived from his ability to appoint magistrates (a power previously held by the censors), his control over Rome’s legions (previously exercised by the Proconsuls), and his position as Rome’s religious leader (Pontifex Maximus). He also had the power to declare war and negotiate treaties with foreign powers. Prefects Augustus revived the position of prefect, following the transition from Republic to Empire. The prefect had responsibility for the day-to-day running of the city of Rome. To enforce his authority, he was given control of Rome’s policie force. The position was appointed by the emperor. Roman emperors Augustus Tiberius Caligula (Gaius) Claudius Nero Galba Otho Vitellius Vespasian Titus Domitian Nerva Trajan Hadrian Antoninus Marcus Aurelius 27 BC – AD 14 AD 14 – 37 AD 37 – 41 AD 41– 54 AD 54 – 68 AD 68– 69 AD 69 AD 69 AD 69 – 79 AD 79 – 81 AD 81 – 96 AD 96 – 98 AD 98 – 117 AD 117 – 138 AD 138 – 161 AD 161 – 180 Granted power by the Senate and Assemblies Son of Augustus’ third wife; adopted by Augustus Great grandson of Augustus; murdered by his enemies Uncle of Caligula; proclaimed emperor by the army Great-great grandson of Augustus; committed suicide Seized power following Nero’s death Appointed by the army, following Galba’s murder Seized power after defeating Otho in battle Seized power after murdering Vitellius Son of Vespasian; died of fever Son of Vespasian; murdered by his enemies Appointed by the Senate Adopted son of Nerva Adopted son of Trajan Adopted son of Hadrian Adopted son of Antoninus 3 Local government Local government under the Republic Cities and towns in Italy were run as independent municipalities, meaning they elected their own officials. Only men could vote and stand for political office. Each city elected four magistrates – the decuriones. The most important officials were the two duumviri, who were responsible for the political running of the city and for the administration of justice. They presided over the curia (town council) and the courts. They also controlled revenue and taxation. The duumviri were the local equivalent of consuls, except they had no military power. The duumviri were assisted by the two aediles, who oversaw public works and various day-to-day activities (looking after the markets, temples and streets). You had to serve as an aedile before you could be elected duumvir. Officials were elected for a term of one year. The curia (town council) was the local equivalent of the Senate, and consisted of 100 former magistrates. It made local laws, and its members were appointed for life. In an emergency, the Council could appoint a Praefectus Iure Dicundo, who was in effect a dictator. He would run the city until the emergency was over. This was the case following the earthquake of 62 AD in Pompeii. Other important magistrates in the city were the quinquennales. They were former duumviri who were elected every five years. They had the power to revise the local citizenship rolls and to appoint former magistrates to the curia. They could also dismiss people from the curia, if they breached the rules (for example, if they committed a crime or if their wealth fell below the required level). The duumviri were selected from among the wealthiest men in the city – mainly because no others could afford the cost of getting themselves elected. Once in office, they would use their influence to gain more political and economic power. Local government under the Empire Under the Empire (i.e. during the 1st century AD), the governing process of Italian cities remained the same, except that local laws and decisions were subject to imperial decree. This meant that the emperor could overrule decisions made by the duumviri and curia. He could also impose new laws upon towns and cities. An example of this was Nero’s decision to ban gladiatorial contests in Pompeii for ten years, following the riots of AD 59. 4