* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Designer Babies and 21st Century Cures

Heritability of IQ wikipedia , lookup

Population genetics wikipedia , lookup

Behavioural genetics wikipedia , lookup

Artificial gene synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Medical genetics wikipedia , lookup

Gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Biology and consumer behaviour wikipedia , lookup

Vectors in gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Site-specific recombinase technology wikipedia , lookup

Human genetic variation wikipedia , lookup

Human–animal hybrid wikipedia , lookup

Genetic testing wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Molecular cloning wikipedia , lookup

Microevolution wikipedia , lookup

History of genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Genetic engineering in science fiction wikipedia , lookup

Genome (book) wikipedia , lookup

Genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

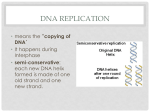

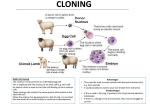

BOOK REVIEW By Patrick Tucker Designer Babies and 21st Century Cures Ian Wilmut, the geneticist who cloned Dolly the sheep, plunges headfirst into the cloning debate in After Dolly. In 1997, a research team led by geneticist Ian Wilmut in Scotland succeeded in cloning a white-faced sheep named Dolly, and plunging the world into a new era of fear, possibility, and speculation. His new book, After Dolly: The Uses and Misuses of Human Cloning, explains the fascinating but complicated cloning process. It also examines key misconceptions that have arisen in the shadow of Dolly, such as the likelihood of creating genetically enhanced “designer babies.” Wilmut puts forward a passionate argument for applying cloning techniques to stem-cell science in order to find cures for the world’s most devastating genetic diseases and disorders, such as Parkinson’s and Hodgkin’s diseases. On a conceptual level, the process of cloning is really not very complicated. DNA is harvested from an adult cell (a mammary cell in the case of Dolly). The DNA is then inserted into the center of a hollowedout egg from a different animal of the same species. With its nucleus removed, the host egg would not contain genetic material from the animal that provided it (but would contain cytoplasm). Once the donor DNA has been inserted, a carefully released burst of electricity convinces the enucleated egg that it has been fertilized, or “activated.” The egg is then inserted into the uterine lining of a third animal (the birthing mother). If the resulting offspring is a genetic match with the original DNA donor but not the donor of the hosting egg or the birthing mother, 48 THE FUTURIST perts have wondered whether the use of the term ‘cloning’ has damaged the field because it is so laden with grim associations and negative baggage. Understandably, the official alternative—’cell nuclear replacement’—is gray and wordy and, as a result, has not caught on.” Recent polling research validates this opinion. While 58% of Americans now favor embryonic stem-cell research, 59% are opposed to using cloning technology to create embryos in order to provide stem cells for therapy, despite the marginal difference between these two processes. “What’s in a name?” Wilmut asks. “In this case, a great deal. These primal cells are the stuff of which medAfter Dolly: The Uses ical dreams are made.” Unlike either animal cloning or reand Misuses of Human productive human cloning (which Cloning Wilmut adamantly opposes), theraby Ian Wilmut and Roger Highfield. peutic cloning involves creating an W.W. Norton & Company. 256 embryo that is a genetic match with pages. $24.95. the human seeking THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH therapy, and then h a r ve s t i n g a n d manipulating stem cells from that emthen the cloning attempt bryo. This process, has been successful. Wilmut writes, ofNeedless to say, in fers a way to depractice cloning is far pendably obtain more difficult. Wilmut genetically and his team extracted compatible tissue material from 277 donor of any kind. Stem cells and implanted 29 cells are harvested embryos into surrogate from an activated mothers, but only one egg that has embryo developed into a reached the blastoIan Wilmut fetus and finally into a cyst stage, roughly live sheep. 200 cells. At this Since his success with Dolly, stage, the embryo is little more than Wilmut has turned his attention to a ball of undifferentiated genetic mathe debate on stem-cell therapy, or terial. By way of comparison, a fully what is sometimes called therapeutic formed human, capable of thought cloning. Ironically, the man who and reason, comprises nearly 10 trilmany consider to be one of the lion cells. giants in the field of cloning research Wilmut defends his work with has mixed views about the term blastocysts on the basis that such itself. genetic material, once created in a “The usual term for the procedure dish, cannot survive on its own, of deriving cells from cloned em- bares no resemblance to an adult of bryos, ‘therapeutic cloning,’ sends any species, and is totally incapable shivers down the spines of many of thought or discomfort. people,” Wilmut writes. “Many ex“Is the blastocyst aware?” he asks. September-October 2006 “Can a blastocyst feel pain? Until nerve connections form between two crucial areas of the developing brain, the cortex and the thalamus, sensations of pain cannot be experienced. This formation takes place much later in pregnancy, around the twenty-sixth week (in humans). There is no pain, no suffering, and thus no cruelty to the blastocyst is possible.” Wilmut doubts the feasibility of “designing babies” and opposes such efforts on ethical grounds. While defending the use of embryonic science and cloning technology to treat or prevent serious diseases, he argues that the compulsion to use the same science to enhance physical or mental attributes in the unborn is not morally justifiable. “Like most people I disapprove strongly of the idea of an embryo coaxed to life for shallow reasons of status, preference, or style. Any such work is unsavory because it reduces children to consumer objects that can be ‘accessorized’ according to the parents’ whims. As many ethicists have argued, love for offspring should not be contingent upon the characteristics they possess, in an ideal world,” Wilmut writes. He believes that much of the language used by the media to describe this possibility reflects an overly optimistic view of the science and its potential: I am skeptical that genetic enhancement is even possible because the genetic control of many traits is so complex. In turn any of the genes involved in any one trait also have effects in many others. In short, we could not predict the effect of changing genes except in the case of inherited diseases associated with errors in a known gene. . . . Any genetic change intended to influence intelligence, say, could also change other aspects of personality in an unpredictable way. By way of example, Wilmut brings up the story of a pair of rich parents who hoped to engineer an intellectually gifted baby only to wind up, years later, with “a sullen adolescent who smokes marijuana and doesn’t talk to them.” R e g a rd l e s s o f it s f e a s i b i l it y, Wilmut is deeply anxious about the prospect of someone using private funding to engineer “a designer baby,” and he recommends strong government regulation to prevent such unethical experimentation. “Despite many people’s almost religious belief in free markets, our experience of the food and pharmaceutical industries shows us that an unregulated market is inappropriate for matters of public health and thus of genetic modification,” he writes. The debate over what might constitute legitimate genetic “therapy” vs. what might be “enhancement” will surely grow more cacophonous in the years ahead. As the science becomes more conclusive and breakthroughs continue to garner media attention, more people will invest both faith and money in cures that are still years away and experiments that may have unfortunate consequences. Yet, as Wilmut himself makes clear, there is also great cause for optimism. In the following decades, we may succeed in eliminating some of the world’s most devastating diseases, much to the relief of humanity as a whole. To help us negotiate the winding path before us, Wilmut puts his trust in that oldest and perhaps most mysterious of human qualities—reason. “Although I have no idea what the future will bring,” he writes, “I am confident that reproductive and genetic technologies will greatly expand our possibilities. By the same token, they will also expand the burden of responsibility. Because of my faith in the majority of people to know right from wrong, I feel the sooner we take on that burden the better.” For the sake of future generations and their health, I hope Wilmut’s faith is well placed. ■ About the Reviewer Patrick Tucker is assistant editor of THE FUTURIST and director of communications for the World Future Society. Scan the Frontiers of Change with Future Survey The Proven Source for Vital Trends, Ideas, and Technologies Shaping Our Turbulent World This esteemed monthly newsletter, edited by interdisciplinary social scientist Michael Marien, provides userfriendly abstracts of new books, articles, and reports on topics that may have a major impact on our future. Future Survey highlights groundbreaking research and the cuttingedge thinking of social critics, thinktank analysis, academic experts, and visionaries. It’s the unique scanning service to help you keep up with our turbulent world. Each monthly issue reviews 50 recent books, articles, and research reports on a wide variety of important trends, forecasts, and policy proposals. A Vital Tool for • Planners • Researchers • Organizational Leaders • Teachers • Consultants No other book review, magazine, journal, or electronic access service comes close to providing as much authoritative, futures-relevant information as Future Survey. Your one-year subscription to Future Survey ($109) includes: • 12 information-packed issues with 50 concise abstracts each. • An annual index. • Special access code to the exclusive, subscriber-only Web site, where you can easily search and review thousands of abstracts from the Future Survey archives. To order: Call 1-800-989-8274 or subscribe securely online at https:// www.wfs.org/fsonlinesub.htm. Please note: Future Survey is included as a benefit for Comprehensive Professional Members of the World Future Society. Visit www.wfs.org/ members.htm for details. THE FUTURIST September-October 2006 49

![2 Exam paper_2006[1] - University of Leicester](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/011309448_1-9178b6ca71e7ceae56a322cb94b06ba1-150x150.png)