* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Dissociative and Somatoform Disorders

Anterograde amnesia wikipedia , lookup

Addictive personality wikipedia , lookup

Impulsivity wikipedia , lookup

Motivated forgetting wikipedia , lookup

Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

Substance use disorder wikipedia , lookup

Bipolar II disorder wikipedia , lookup

Gender dysphoria in children wikipedia , lookup

Retrograde amnesia wikipedia , lookup

Broken windows theory wikipedia , lookup

Repressed memory wikipedia , lookup

Anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Bipolar disorder wikipedia , lookup

Autism spectrum wikipedia , lookup

Social anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Eating disorders and memory wikipedia , lookup

Rumination syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

Eating disorder wikipedia , lookup

Panic disorder wikipedia , lookup

Schizoaffective disorder wikipedia , lookup

Mental disorder wikipedia , lookup

Memory disorder wikipedia , lookup

Psychological trauma wikipedia , lookup

Separation anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Depression in childhood and adolescence wikipedia , lookup

Treatment of bipolar disorder wikipedia , lookup

Asperger syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Causes of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Factitious disorder imposed on another wikipedia , lookup

Glossary of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Antisocial personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

Conduct disorder wikipedia , lookup

Spectrum disorder wikipedia , lookup

Generalized anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Diagnosis of Asperger syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Child psychopathology wikipedia , lookup

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders wikipedia , lookup

Munchausen by Internet wikipedia , lookup

Narcissistic personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

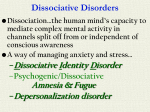

Depersonalization disorder wikipedia , lookup

Conversion disorder wikipedia , lookup