* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy wikipedia , lookup

Behaviorism wikipedia , lookup

Behaviour therapy wikipedia , lookup

Emotional lateralization wikipedia , lookup

Dyadic developmental psychotherapy wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Psychological behaviorism wikipedia , lookup

Residential treatment center wikipedia , lookup

Psychophysics wikipedia , lookup

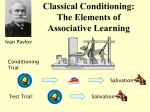

Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy William C Follette and Georgia Dalto, University of Nevada Reno, Reno, NV, USA Ó 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Abstract Classical conditioning describes associative learning where stimuli are sometimes paired to produce clinical problems including most anxiety disorders. Extinguishing problematic responses that arise through classical conditioning is the focus of many psychotherapy procedures. This article describes the basic principles of classical conditioning, how understanding these principles helped clarify our understanding of the etiology of clinical problems, and how exposure-based treatments were developed to reduce or eliminate these problems. Recent cognitive explanations regarding the change process in humans are described. Finally, some attempts to add pharmacological adjuncts to improve the efficacy of exposure are reviewed. One of the most common reasons people seek psychotherapy is because of anxiety or fear about some situation or object. There are many accounts for how these emotional states develop, but when people present for therapy it is often because their avoidance of these fearful situations interferes with some aspect of their desired role functioning. One of the most commonly used technical procedures in psychotherapy is exposure, and it is particularly effective in the treatment of these types of clinical presentations. The effectiveness of exposure hinges primarily on an understanding of classical conditioning, also called Pavlovian or respondent conditioning. Classical conditioning is commonly defined as a process whereby a previously neutral stimulus comes to exert control over a response through pairing of the neutral stimulus with a stimulus that naturally (i.e., with no prior training) elicits the response. Since its accidental discovery by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov in the late-nineteenth century, classical conditioning has been applied to many normal as well as clinically significant behaviors such as those characterizing anxiety disorders and addiction. Using principles derived from classical conditioning theory and contemporary extensions of the theory, behavior therapies have been developed to reduce the fear and anxiety responses that interfere with normal functioning. The Procedures and Processes of Classical Conditioning Classical conditioning is the most straightforward example of associative learning where stimulus–stimulus associations develop. According to the above description, the stimulus that naturally elicits the response is known as the unconditional stimulus (US), the naturally occurring response is known as the unconditional response (UR), the previously neutral stimulus is known (following conditioning) as the conditional stimulus (CS), and the response that comes under the control of the CS is known as the conditional response (CR). The process was first outlined by Pavlov during his study of the salivary response in dogs. Food in the mouth naturally produces a salivary response to aid digestion, but Pavlov noticed that his subjects began to salivate to the sound of a bell that accompanied the opening of the laboratory door during feeding time. 764 In a series of now classic experiments, Pavlov demonstrated that the bell became a CS for the food (US) and that the CR of salivation was very similar to the natural salivary response (UR) elicited by the food. For the better part of a century, contiguity between CS and US was commonly cited as an essential determinant of the successful conditioning of a response. Optimal conditions were said to be those in which the CS simply occurred immediately before onset of the US. However, more recently, the focus has shifted from contiguity between the CS and US to the amount of information supplied by the CS about the occurrence of the US (Rescorla and Wagner, 1972). For example, if a US occurs as frequently (or more frequently) in the absence of the CS as in its presence, very little conditioning will occur. The CS in this case is simply a poor predictor of the onset of the US. To exemplify the basic procedure by which a conditional response to a previously neutral stimulus is established, consider the following example. A small child with no fear of dogs is playing near a dog’s food bowl. As the dog approaches, the unsuspecting child reaches out playfully to pet it. The dog (CS), presumably guarding its food, nips the child (US), causing minor tissue damage and producing a fear response in the child (UR; e.g., crying, retreating, etc.). If the child emits a fear response (CR) when next confronted with the sight of a dog (CS) and in the absence of another nip, conditioning is shown to have occurred. Earlier descriptions of classical conditioning also stated that the CR was generally topographically similar to the UR. That is, the CR looked the same. It is now recognized that the CR may look different from the UR depending on the species of the organism. In humans, the nature of the CR may vary substantially from the UR. Generalization and Discrimination Two other processes are relevant to a discussion of classical conditioning in clinical psychology: generalization and discrimination. In stimulus generalization, the CR occurs to stimuli that are similar in some way to the CS (but to which the response has never been conditioned). If the child was bitten by a Golden Retriever, but then comes to emit the fear response in the presence of German Shepherds and Chihuahuas, stimulus generalization is said to have occurred. In nonverbal organisms, generalization occurs on the dimension of some shared property of the stimulus. For example, if a dog were International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, Volume 3 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.21052-0 Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy classically conditioned to a tone of a certain frequency, then similar sounding tones could also elicit a CR. In humans, language allows other generalization to occur along dimensions that may share no formal properties with the original CS but have acquired a relationship with the CS that can produce a CR. For example, only humans can show conditioning to the sight of a dog (CS) and also to the word ‘dog’ or the name ‘Rover’ or a leash, without prior conditioning once the animal has become a CS. In stimulus discrimination, the CR does not occur to stimuli that differ sufficiently from the original CS. In this case, the child would only fear Golden Retrievers, and would not emit that response to other breeds. Exposure to the US or the CS: Habituation and Extinction The process by which a fear response can be learned was described above. This same response can also be inhibited. One or both of the following processes can be used clinically to reduce fear responding. The first process is called habituation and it occurs through the repeated presentation of the US without the CS. The CS comes to have no predictive value for the occurrence of the US such that later presentations of the CS do not elicit a CR. The other process that can lead to inhibition of the CR is called extinction. Extinction is when the CS is presented without an accompanying US. A tone may be presented to a dog but food no longer follows. Eventually, the predictive value of the CS is diminished such that the CS no longer produces a CR. Classical Conditioning and Avoidance in the Development of Psychopathology The example of the child and the dog demonstrates the potential for classical conditioning to play a part in the etiology of a severe and persisting fear of dogs, or simple phobia, and it identifies a pathway through which many other fear or anxiety related disorders are thought to develop. Watson and Rayner (1920), in their classic Little Albert experiment, effectively conditioned fear in an infant. After allowing the child to play with a white laboratory rat (to which he showed no previous fear), the researchers followed presentation of the rat (CS) with a loud bang on an iron bar behind Little Albert’s head. The loud noise (US) elicited a startle response from the child (UR), accompanied by crying. After a number of trials with this pairing, Little Albert began to emit a fear response (CR) to presentation of the rat alone, a response that also generalized to other white, furry objects. The clinical significance of this response (i.e., its persistence and the degree of functional impairment it produced) is not known, as Little Albert did not participate in follow-up studies and is thought to have died at age six (Beck et al., 2009). However, one of Watson’s later graduate students, Mary Cover Jones, did demonstrate that phobic responses could be reduced by gradually exposing a child to the feared object (Jones, 1924). People can also learn fear responses without directly experiencing the CS–US pairing, but can instead learn through observation. When someone observes a dog bite a person resulting in injury and distress, the observer may acquire a conditioned response. This is called vicarious learning. One can acquire even more subtle associations such as when a child 765 is holding a parent’s hand and notices a hand squeeze and protective movement when the parent sees a strange, large dog. Though many adults with specific phobias can recall a CS–US pairing, a large number of such people have no such recall. While it is possible that some of these reports are simply failures of memory, this also suggests that vicarious learning can account for some proportion of episodes of conditioning. Not all stimulus–stimulus relationships are equally easily established (Garcia and Koelling, 1966). Certain modalities of associations are learned more readily than others. For example, pain is more readily associated with visual or auditory stimuli than gustatory stimuli (Rachman, 1991). Conversely, internal stimuli are more readily conditioned with gustatory stimuli. Thus, it is common for taste aversions to be acquired after an episode of nausea or vomiting (Bernstein, 1999). Individual Differences Not everyone who experiences a potentially traumatic event will go on to demonstrate the pathological avoidance or exaggerated startle responses characteristic of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), nor indeed does everyone exposed to a fear-inducing US develop conditioned fear or a phobic response to the accompanying CS. Again, classical conditioning principles may help shed some light on this individual difference. The concept of ‘conditioned inhibition’ suggests that when the CS is a compound stimulus (e.g., all the myriad stimuli that make up the context in which an event occurs), the stimuli that signal the absence of the US will inhibit conditioned responding. Consider the example of a child who is with her mother when a bomb goes off on a bus. Because the presence of the child’s mother has, through previous conditioning, come to signal safety (or the absence of danger), the child may not develop a conditioned fear response to other stimuli present at the time of the explosion (e.g., loud noises, buses, etc.). In this case, the child’s mother has served as a conditioned inhibitor and effectively protected the child from developing a pathological fear response to the neutral stimuli. The principles of stimulus generalization and discrimination can also help explain individual differences in psychopathology. When fears become pervasive (such as when a rape victim comes to fear all men), it is likely due to extensive stimulus generalization. Many things have come to participate in a stimulus class with the original CS because they are similar on some relevant dimension (e.g., they are all male). Alternatively, very circumscribed fears are the result of appropriate stimulus discrimination (as when an individual avoids the intersection at which he had a serious automobile accident but is still able to drive through all other parts of the city). Individual differences in reactivity to potentially fearinducing events also depend on the unique learning histories of the individual. One way histories differ is in terms of prior experience with stimuli. The Kamin ‘blocking’ effect states that a stimulus that is part of a compound stimulus will fail to produce conditioning if other stimuli in the compound have already been conditioned (Kamin, 1969). A boy who has come to emit a fear reaction at the sight of soldiers in uniform because they were present when he arrived home to find that his mother had been killed in an airstrike, may not come to fear news reporters who are present (in addition to soldiers) when 766 Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy the rest of his family is killed in a similar attack 2 weeks later. The blocking effect is thought to occur because the second stimulus does not provide any new information about the US beyond that supplied by the original CS. Avoidance If classically conditioned fear responses reduce on their own when either the CS is presented without the US, or the US is presented without the CS, then why don’t fear responses naturally ameliorate? In fact, some do (Staley and O’Donnell, 1984). Epidemiologic studies do show that children endorse a higher number of feared objects than do adults, though some fears develop later (Merckelbach et al., 1996). What accounts for the diminution of the feared objects as people get older? The answer is likely natural exposure that occurs during the course of childhood. If a child is showing a fear of a dog known to be friendly, parents or the dog owner may well slowly present the dog for petting by the child or may model petting after which the child does the same. This kind of natural exposure produces extinction and is likely why the prevalence of specific phobias decreases over time. What accounts for when fear responses persist? A version of the answer was offered by O.H. Mowrer (1956) called twofactor learning theory. In its simplest form, the theory argues that fear responses are classically conditioned in roughly the way described above. It is the second factor that interferes with the natural reduction in the fear response: avoidance. Avoidance occurs when someone begins to encounter either the feared stimulus, the US, or stimuli that have become conditioned to elicit the feared response. As the fear rises, the person avoids contact with either the CS or US. This avoidance behavior is negatively reinforced, i.e., made more likely to occur (see operant learning) by the reduction or removal of fear or anxiety. The clinical implication of this avoidance is that the person does not experience either habituation or extinction, because the aversive stimulus in never repeatedly contacted so that habituation or extinction would occur. Going back to the simple example of the person fearful of dogs, when such a person sees the dog from some distance away, a mild aversive response may be noted. As the dog gets closer, the anxiety rises. If the person turns around and exits the situation, the anxiety or fear quickly reduces. This reduction in the aversive emotion negatively reinforces avoidance. In the short run, the aversive state is removed thereby strengthening the avoidance. Had the person continued to approach to dog in spite of the growing anxiety, the person would have come right up to the feared object, the dog, and not have experienced a bite. If the approach behavior continued in other episodes, the fearful response to dogs would have habituated. Though Mowrer’s original formulation has been extended to include cognitive components to address how widespread avoidance of various stimuli can become, its treatment implications are still generally relevant, as will be discussed below. Exemplars People with PTSD show exaggerated startle responses and report intense fear reactions to many stimuli that were present at the time of the original traumatic incident (e.g., the sound of a helicopter for a combat veteran, the presence of crowds for a survivor of a mass shooting, darkness or the smell of alcohol for someone who was raped in an alleyway outside a bar late at night). In all of these examples, previously neutral stimuli have come to elicit a fear response very similar to that elicited at the time of the trauma. The stimuli that elicit the fearful response are external to the person. Panic disorder (sometimes described as fear of fear) is characterized by intense fear responses to interoceptive (as well as external) cues such as a pounding heart, dizziness, shortness of breath, sweaty palms, or symptoms that may have preceded a full-blown panic attack in the past. In this case, the initial (and extremely unpleasant) panic attack can be thought of as the US, fear of dying may be the UR, the early symptoms or environmental conditions as the CS, and the fear response as the CR. Since panic attacks may be perceived as occurring randomly, any aspect of the environment may become a CS as might any unpleasant physical sensation. In some cases, panic attacks may lead to the development of agoraphobia, literally a fear of public (open) spaces, but clinically a fear of being in a public place where one feels trapped or faces embarrassment should a panic attack ensue. The person tries to identify situational cues that will allow him or her to avoid a panic attack. Since the cues are difficult to detect, the person generalizes those situations broadly and avoids more and more activities that take place away from the relative safety of one’s home. Anxiety disorders in general rely on treatment components that derive from classical conditioning models. An individual with social phobia may learn to avoid all manner of social interactions or performance situations, because characteristics of these contexts have been associated with humiliating experiences in the past. Certainly, addictive behaviors have many classically conditioned elements to them. The sight of needles, drug paraphernalia, the olfactory or visual cues, or the appearance of another drug user may elicit cravings in alcohol, opioid, or stimulant abusers. Using Classical Conditioning in Psychotherapy In addition to helping explain the etiology of many forms of psychopathology, an understanding of classical conditioning principles has given rise to several forms of behavioral psychotherapy. Beginning with Mary Cover Jones, ‘counterconditioning’ involved the pairing of a feared stimulus with an appetitive (desirable) stimulus such that the response to the former was replaced with the response to the latter. Sensitization One line of therapy based on classical conditioning was developed to reduce behaviors desired by patients but that were recognized to be unhealthy or otherwise undesirable. One of the more common examples can be found in the history of the treatment of alcohol dependence where conditioned taste aversions are used to treat this difficult problem. As with many clinical problems, treatment can be understood from either a classical or operant conditioning perspective (or both). One Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy treatment strategy has been to classically condition the taste or smell of alcohol with nausea by using conditioned taste aversion procedures (Revusky, 2009; Lemere, 1987; Reily and Schachtman, 2009). As mentioned earlier, gustatory–nausea relations are more easily learned than some other sensory modalities. Two procedures are most common. In one, after the risk of alcohol withdrawal has been managed, the patient is given a taste of a preferred alcohol followed by an emetic drug (Lemere, 1987). Emetics induce nausea or vomiting. The notion is that alcohol when paired with the emetic will produce a response of nausea to the alcohol in the absence of the emetic. A variation on this approach is the use of disulfiram (AntabuseÔ) in alcohol treatment programs (cf Krampe et al., 2011; Jørgensen et al., 2011; Alharbi and el-Guebaly, 2013). Disulfiram is another commonly used drug that provides a similar learning history. Disulfiram interferes with the normal metabolism of alcohol resulting in a buildup of acetaldehyde. This can lead to nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and other unpleasant side effects when one drinks alcohol, thus creating a conditioned taste aversion. Alcohol treatment programs have also tried to use aversive electrical stimulation paired with alcohol taste to create a conditioned aversion to alcohol as well. There is less evidence that the shock–alcohol pairing is clinically as effective when compared to the emetic–alcohol pairing, though the limited evidence is not consistent (Smith et al., 1997; Cannon et al., 1981; Lamon et al., 1977). There have been ethical objections to conditioned aversive therapies (Nathan, 1985; Wilson, 1987), but some patients find them a better alternative than other treatment programs or compared to continued addiction. Conditioned aversion therapies have been applied to a variety of behaviors, the consequences of which can have deleterious effects for those who exhibit them, or for society. Aversion therapy has been adapted to smoking, cocaine use, sexual deviations including child molestation, and paraphilias, to name some examples (Rachman and Teasdale, 1969). Covert Sensitization Though not purely involving classical conditioning procedures, covert sensitization, also called covert conditioning, has been used to treat maladaptive approach behaviors including but not limited to problematic compulsions, sexual behaviors, alcoholism, obesity, nail biting, and smoking (Cautela and Kearney, 1986; Cautela, 1971). This procedure was developed as an alternative to the application of aversive stimuli such as an electric shock or an emetic (cf Krampe et al., 2011; Jørgensen et al., 2011; Alharbi and el-Guebaly, 2013). Covert sensitization makes use of aversive imagery that may be easier to produce outside of the laboratory or treatment environment. In brief, the subject is taught to imagine himself as about to engage in some desired but problematic behavior such as taking a drink. Vivid cues are provided to enhance the image. As the person is about to take the drink, he is instructed to imagine an uncomfortable feeling taking over that results in a further image of feeling profound nausea followed by vomiting. The vomiting is imagined to result in vomiting on oneself, the table, and perhaps others. The person is instructed to imagine odors, being embarrassed, and perhaps other aversive consequences. This process is repeated. In some versions, the person 767 may be taught to imagine being about to take a drink, feeling the beginning of the nausea, and stopping, which is followed by a feeling of relief and pride that one resisted the drink. It is not easy to measure how well the covert stimuli are produced or to assess how well or how willing one is able to produce the aversive covert stimuli. Nevertheless, this procedure can be useful when one behaves under the control of a reinforcer that is inappropriate or leads to undesirable consequences. Systematic Desensitization Joseph Wolpe was among the first to use the term ‘systematic desensitization’ for his approach to reducing fear responses to anxiety-producing stimuli (Wolpe, 1961). In this treatment, a relaxation response is trained in advance of exposure to the feared stimulus. When the feared stimulus is introduced, the client is instructed to engage in the relaxation response, which is believed to be physiologically incompatible with the fear response (Wolpe originally use the term ‘reciprocal inhibition’; see Wolpe, 1958 for an early explanation of the intervention). Typically, there are three steps to this treatment. One is to identify a hierarchy of situations that are increasingly fearprovoking for the patient. In the case of acrophobia (a fear of heights), the patient and therapist list a series of such scenes from looking at a short step ladder to standing in front of this ladder to stepping on the first step. Additional scenes are constructed culminating with the most challenging scene that might be standing on the ledge of a tall building and looking down at the street below. In a commonly practiced version of this treatment, the scenes are sorted from the lowest arousing scene to the highest. Some number of sessions are used to teach the subject relaxation skills. Once those skills are learned, the therapist has the person imagine approaching the first element of the hierarchy until they notice some uneasiness, at which point they are told to use their relaxation skills until they become comfortable. This is repeated until that element of the hierarchy no longer produces anxiety or fear, and then the next scene is presented. This process is repeated until the client completes the hierarchy. Some have proposed that the process involves extinction, while others suggest habituation takes place (Watts, 1979). In either event, the previously avoided stimuli are contacted and the anxiety response is sufficiently reduced to allow normal functioning. When treatment is designed as described above, it is often experienced as more palatable for both the client and therapist. As research has shown, it is not actually necessary for the hierarchy of scenes to be presented in a particular order; nor is it essential that the client have mastered a relaxation response; and some data indicate that in vivo exposure to elements in the hierarchy are perhaps more effective than imaginal techniques (see Marks, 1978 for a review). Thomas Stampfl introduced the technique of ‘flooding,’ in which the client is exposed to large doses of the feared stimulus and prevented from escaping until the fear response subsides (Stampfl and Levis, 1967). Contemporary treatments such as prolonged exposure for trauma and exposure and response prevention for obsessivecompulsive disorder (OCD) were built on this tradition of harnessing the power of classical conditioning to replace maladaptive responses with more adaptive ones. What all these 768 Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy techniques have in common is that they involve exposing the client to the feared stimulus instead of allowing him or her to continue to avoid it. Over the last 25 years, several difficult-to-treat problems have been successfully addressed by creative exposure procedures. Panic disorders have been treated by making use of interoceptive exposure where some of the symptoms of panic are produced but without the panic attack itself (Barlow et al., 1989; Barlow and Craske, 1989). Many who experience panic attacks become hypersensitive to normal physiological responses such that when they occur, fear of a panic attack ensues. In interoceptive exposure procedures, a variety of exercises are used to bring about some of those internal sensations so that the fear of a panic attack does not occur when some cues occur. For example, patients are taught to hyperventilate to experience some lightheadedness. Similarly, a patient may sit on a chair that spins around sufficiently to induce mild dizziness. A variety of exercises are utilized to expose patients to bodily cues that do not become panic attacks. OCD is another clinical problem that has been usefully treated by exposure and response prevention (Franklin and Foa, 2011). In OCD, patients are exposed to that about which they obsess and are prevented from exhibiting the compulsive behavior that they use to reduce the obsessions. For instance, someone who obsessed about germs might be exposed to a dirty article of clothing for long periods of time and not allowed to wash his hands. Debate exists with regard to the mechanisms by which exposure reduces fear and anxiety (McSweeney and Swindell, 2002). Traditionally, this process has been described as extinction, whereby the CR fails to occur following repeated presentation of the CS without the US. The CR is said to extinguish as a result of this procedure. The idea is that the link between CS and US is severed, so that the CS no longer predicts the US. According to Rescorla–Wagner model, this procedure would diminish the information about the US provided by the CS. However, McSweeney and Swindell (2002) examined the substantial body of literature available at the time and concluded that there is considerable evidence to suggest that the process known as extinction actually relies on the even more basic principle of habituation. Habituation is defined as “a decrease in responsiveness to a stimulus when that stimulus is presented repeatedly or for a prolonged time” (p. 364–365). When applied to the senses, habituation is known as ‘sensory adaptation’ and it is a process so pervasive that we often take it for granted (consider the experience of walking into a room with a strong offensive odor and suddenly realizing half an hour later that you can no longer smell it). The case presented by McSweeney and Swindell suggests that repeated or prolonged exposure to the CS will cause a decrease in the probability or likelihood of the CR through this process of habituation. It remains an empirical question whether habituation occurs to the CS through repeated or prolonged exposure even when the CS continues to be followed by the US. Treatments based on classical conditioning principles also consider such effects as stimulus generalization and discrimination, blocking, and conditioned inhibition. The tendency of fears to generalize to additional stimuli can make treatment challenging, as many more stimuli than those involved in the original fear-inducing event may need to be targeted in treatment. On the other hand, one expects that treatment produces new learning (i.e., to not fear the stimuli used in exposure) that will generalize to additional feared stimuli. However, the situation is complicated, as habituation and extinction appear to generalize less readily than the original conditioning (McSweeney and Swindell, 2002). Stimulus discrimination can be encouraged by training the individual to distinguish between the original feared stimulus and similar (but different) stimuli. This process may help prevent the generalization of the fear response following the original conditioning event. Blocking could potentially prevent new learning from occurring such that it may be more effective to conduct exposures to one feared stimulus at a time; pairing a reconditioned stimulus with one that is still feared may render the still feared stimulus redundant (i.e., it does not provide any new information about the situation). The impact of conditioned inhibition on psychotherapeutic techniques informed by classical conditioning may be more complicated. While the presence of a stimulus that has come to signal safety may protect the individual from fear conditioning to begin with, such ‘safety signals’ may also impede the process of extinction/habituation during exposure. It is thought that safety signals (such as empty medication bottles or being accompanied by a significant other during exposure exercises) prevent the individual from fully contacting the feared stimulus so that when exposed to the stimulus in the absence of the safety signals, any apparent positive effects of the exposure disappear. Cognitive Considerations Certainly, exposure-based therapies are among the most robust intervention for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Exposure relies on some aspects of classical conditioning principles augmented by an operant understanding of the role of avoidance in the maintenance of anxious or fearful response. Two observations have stimulated theorizing about a cognitive explanation for how exposure works. First, not everyone who undergoes an exposure-based treatment shows improvement (Choy et al., 2007). This implies that our understanding of the dimensions of the CS or CR is not fully adequate. Second, the treatment of two difficult clinical problems, PTSD and OCD, has engendered theorizing about what happens in humans who can verbalize their experiences (Foa and Kozak, 1986). In PTSD, a wide variety of stimuli, not easily categorized, can produce fearful responding. In OCD, obsessions are cognitions and patients provide elaborate explanations for the source of the obsessions and the functions of the compulsions. One of the more elaborated information processing/ cognitive models was called emotional processing theory (EPT) (Foa and Kozak, 1991; Foa et al., 2006). EPT suggests that effective treatments for fear and anxiety, including exposure, produce their effects by introducing accurate information to alter existing, or create new, fear structures. A fear structure contains memories about sensory information about the feared situation, the avoidance behaviors and one’s reactivity to the situations, and information about the interpretations relating the stimuli and responses. The basis of the prolonged exposure, an effective but not the only treatment for PTSD, is that fear Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy structures associated with the traumatic memory entail incorrect associations between stimuli and responses during the trauma and its subsequent meaning. The set of stimuli recognized and responded to as dangerous is too broad, meaning that fear is experienced to a wider set of stimulus conditions. The person also understands their responses as incompetent in indicating they cannot cope. This results in an inability to take in new experiences that would alter their emotional processing. Prolonged exposure putatively works by promoting alterations of the fear structures through systematic confrontation of trauma related stimuli (using imaginal exposure) with discussion of the experience in order to help disconfirm the problematic beliefs. The result is the modification of the problematic fear structure or the creation of another more adaptive one. Not everyone agrees with the need for or the accuracy of this conceptualization and some suggest genetic and individual difference variables warrant attention in addition to remaining aware of advances in associative learning (e.g., Mineka and Thomas, 1999; Mineka and Oehlberg, 2008). In either case, as the verbal constructions of the fear-evoking stimuli get more elaborated, so too does theorizing. This perhaps follows from the natural language patients use to discuss fearful situations and responses to them, as well as the Rescorla and Wagner use of the concept of information contained in the relationship between the CS and US, again a use of language that promotes a more mentalistic interpretation of emotional responding and its treatment. Future Directions New technologies such as virtual reality are being applied to simulate in vivo exposure to otherwise difficult-to-create stimulus conditions (see Virtual Reality in Psychotherapy). For example, virtual reality goggles and sounds have been used to present combat situations for those who show clinically significant fear and anxiety responses following wartime experiences. This same technology has been used to present cues for high-risk situations such as gambling opportunities and smoking situations where the cues themselves may be conditional stimuli for these inappropriate behaviors or discriminative stimuli from an operant learning perspective. Virtual reality scenarios can be programmed for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder where many different kinds of stimuli can elicit anxiety. Increasingly, technology is expanding into the therapy environment. It is clear from the principles of change purported to underlie many of the empirically supported treatments for anxiety that classical conditioning principles have contributed significantly to the arsenal of interventions currently available to psychotherapists. However, the field would likely benefit from the further explication of the precise mechanisms that account for the improvements seen with these therapeutic techniques. Among these are the issue of whether extinction is a distinct process from habituation, how the unique learning history of the client can assist or impede treatment, and the extent to which classical and operant conditioning interact both in the etiology and the resolution of psychopathology. 769 Interesting pharmacologic interventions that possibly affect mechanisms of memory (re)consolidation are currently being researched. There is some evidence that propranolol, a b-adrenergic blocker, may reduce PTSD symptoms, but the ethics of such interventions have been debated (Donovan, 2010). There is evidence that the extinction of fear is mediated in the basolateral amygdala by the activation of N-methylD-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. The drug D-cycloserine can indirectly enhance that activity and has been shown to enhance fear extinction in exposure procedures in both animals and humans, though that effect may only be present if fear is lowered during a session (Smits et al., 2013). Given the ubiquity of anxiety disorders and the public health costs in terms of treatment, resource utilization, and lost productivity, it is likely that procedures to make extinctions procedures more available and cost-effective will continue to evolve. See also: Behavior Therapy: Background, Basic Principles, and Early History; Exposure Therapies and Stress Inoculation: A Brief Overview; Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder across the Life Span; Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia Across the Lifespan; Phobias Across the Lifespan; Reinforcement, Principle of; Social Phobia across the Lifespan; Virtual Reality in Psychotherapy. Bibliography Alharbi, F.F., el-Guebaly, N., 2013. The relative safety of disulfiram. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment 12, 140–147. Barlow, D.H., Craske, M.G., 1989. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic. Graywind Publishing Company, New York. Barlow, D.H., Craske, M.G., Cerny, J.A., Klosko, J.S., 1989. Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behavior Therapy 20, 261–282. Beck, H.P., Levinson, S., Irons, G., 2009. Finding little Albert: a journey to John B. Watson’s infant laboratory. American Psychologist 64, 605–614. Bernstein, I.L., 1999. Taste aversion learning: a contemporary perspective. Nutrition 15, 229–234. Cannon, D.S., Baker, T.B., Wehl, C.K., 1981. Emetic and electric shock alcohol aversion therapy: six- and twelve-month follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 49, 360–368. Cautela, J.R., 1971. Covert conditioning. In: The Psychology of Private Events: Perspectives on Covert Response Systems. Academic Press, New York, pp. 109–130. Cautela, J.R., Kearney, A.J., 1986. The Covert Conditioning Handbook. Springer, New York. Choy, Y., Fyer, A.J., Lipsitz, J.D., 2007. Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clinical Psychology Review 27, 266–286. Donovan, E., 2010. Propranolol use in the prevention and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans: forgetting therapy revisited. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 53, 61–74. Foa, E.B., Huppert, J.D., Cahill, S.P., 2006. Emotional processing theory: an update. In: Rothbaum, B.O. (Ed.), Pathological Anxiety: Emotional Processing in Etiology and Treatment. Guilford Press, New York. Foa, E.B., Kozak, M.J., 1986. Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin 99, 20–35. Foa, E.B., Kozak, M.J., 1991. Emotional processing: theory, research, and clinical implications for anxiety disorders. In: Safran, J.D., Greenberg, L.S. (Eds.), Emotion, Psychotherapy, and Change. Guilford Press, New York. Franklin, M.E., Foa, E.B., 2011. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 7, 229–243. Garcia, J., Koelling, R.A., 1966. Relation of cue to consequence in avoidance learning. Psychonomic Science 4, 123–124. Jones, M.C., 1924. The elimination of children’s fears. Journal of Experimental Psychology 7, 383–390. Jørgensen, C.H., Pedersen, B., Tønnesen, H., 2011. The efficacy of disulfiram for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 35, 1749–1758. 770 Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy Kamin, L.J., 1969. Predictability, surprise, attention and conditioning. In: Campbell, B.A., Church, R.M. (Eds.), Punishment and Aversive Behavior. AppletonCentury-Crofts, New York. Krampe, H., Spies, C.D., Ehrenreich, H., 2011. Supervised disulfiram in the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a commentary. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 35, 1732–1736. Lamon, S., Wilson, G.T., Leaf, R.C., 1977. Human classical aversion conditioning: nausea versus electric shock in the reduction of target beverage consumption. Behaviour Research and Therapy 15, 313–320. Lemere, F., 1987. Aversion treatment of alcoholism: some reminiscences. British Journal of Addiction 82, 257–258. Marks, I., 1978. Behavioral psychotherapy of adult neurosis. In: Garfield, S.L., Bergin, A.E. (Eds.), Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change: An Empirical Analysis, second ed. Wiley, New York. McSweeney, F.K., Swindell, S., 2002. Common processes may contribute to extinction and habituation. Journal of General Psychology 129, 364. Merckelbach, H., de Jong, P.J., Muris, P., van den Hout, M.A., 1996. The etiology of specific phobias: a review. Clinical Psychology Review 16, 337–361. Mineka, S., Oehlberg, K., 2008. The relevance of recent developments in classical conditioning to understanding the etiology and maintenance of anxiety disorders. Acta Psychologica 127, 567–580. Mineka, S., Thomas, C., 1999. Mechanisms of change in exposure therapy for anxiety disorders. In: Dalgleish, T., Power, M.J. (Eds.), Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, New York. Mowrer, O.H., 1956. Two-factor learning theory reconsidered, with special reference to secondary reinforcement and the concept of habit. Psychological Review 63, 114–128. Nathan, P.E., 1985. Aversion therapy in the treatment of alcoholism: Success and failure. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 443, 357–364. Rachman, S., 1991. Neo-conditioning and the classical theory of fear acquisition. Clinical Psychology Review 11, 155–173. Rachman, S., Teasdale, J., 1969. Aversion Therapy and Behaviour Disorders: An Analysis. Reily, S., Schachtman, T.R. (Eds.), 2009. Conditioned Taste Aversion: Behavioral and Neural Processes. Oxford Press, New York. Rescorla, R.A., Wagner, A.R., 1972. A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In: Black, A.H., Prokasy, W.F. (Eds.), Classical Conditioning II. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York. Revusky, S., 2009. Chemical aversion treatment of alcoholism. In: Schachtman, T.R. (Ed.), Conditioned Taste Aversion: Behavioral and Neural Processes. Oxford University Press, New York. Smith, J.W., Frawley, P.J., Polissar, N.L., 1997. Six- and twelve-month abstinence rates in inpatient alcoholics treated with either faradic aversion or chemical aversion compared with matched inpatients from a treatment registry. Journal of Addictive Diseases 16, 5–24. Smits, J.A.J., Rosenfield, D., Otto, M.W., Marques, L., Davis, M.L., Meuret, A.E., Simon, N.M., Pollack, M.H., Hofmann, S.G., 2013. D-cycloserine enhancement of exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder depends on the success of exposure sessions. Journal of Psychiatric Research 47, 1455–1461. Staley, A.A., O’Donnell, J.P., 1984. A developmental analysis of mothers’ reports of normal children’s fears. Journal of Genetic Psychology 144, 165–178. Stampfl, T.G., Levis, D.J., 1967. Essentials of implosive therapy. A learning-theory based psychodynamic behavioral therapy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 72, 496–503. Watson, J.B., Rayner, R., 1920. Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology 3, 1–14. Watts, F.N., 1979. Habituation model of systematic desensitization. Psychological Bulletin 86, 627–637. Wilson, G.T., 1987. Chemical aversion conditioning as a treatment for alcoholism: a reanalysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy 25, 503–516. Wolpe, J., 1958. Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition. Standford University, Stanford, CA. Wolpe, J., 1961. The systematic desensitization treatment of neuroses. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 132, 189–203.