* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 4 Empirical Results. - Econ

Private equity in the 2000s wikipedia , lookup

History of investment banking in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Interbank lending market wikipedia , lookup

Algorithmic trading wikipedia , lookup

Investor-state dispute settlement wikipedia , lookup

Systemic risk wikipedia , lookup

Investment banking wikipedia , lookup

Private money investing wikipedia , lookup

Socially responsible investing wikipedia , lookup

Market (economics) wikipedia , lookup

Environmental, social and corporate governance wikipedia , lookup

Private equity secondary market wikipedia , lookup

Financial crisis wikipedia , lookup

Stock trader wikipedia , lookup

Investment fund wikipedia , lookup

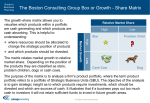

Are Investors Uninformed or Misinformed? A Proposition and a Test. James Kurt Dew 401 Ocean Drive, Apt 411 Miami Beach, FL 33139 USA Abstract: Fama and French (2006) show passive investment creates outsider efficient portfolio choice when inside information is exogenous. However, in Kane’s alternative, investor passivity leads to outsiders’ demise. We show that both results are consistent with the Fama-French analysis. It is the initial conditions that differ. Exogenous inside information –learned but not disclosed – produces Fama-French results. Kane assumes inside information is endogenous – generated “creatively” to maximize insider wealth. This difference is decisive for passive investors. A test shows that Mexico, Turkey and Thailand markets behave as though misinformed; German markets, as though better informed; and United States, best informed. JEL Codes: G11, G15, G21, G28 Key words: rational investors, liberalized markets, CAPM, financial disclosure. 1 6/29/2017 Are Investors Uninformed or Misinformed? A Proposition and a Test. 1 Introduction. The Theory of Finance is based on implicit moral underpinnings. We forget this at our risk. How inside information influences portfolio choice in liberalized financial markets is the focus of this article. It extends a result due to Fama and French (2006). These authors show that after removing one of the CAPM assumptions, the assumption that all investors have equal information – outsiders (investors who possess incomplete information) will ultimately hold the same efficient portfolios chosen by insiders. Suppose, as Fama-French (2006) assumes, insiders provide outsiders with no information. Outsiders, by repeatedly choosing the market portfolio, will ultimately hold a portfolio arbitrarily close to insiders’ optimum portfolio. In this case outsiders need not expend significant resources in a search for the optimal portfolio. They simply need to hold the market, as they might do for example by purchasing shares of an index fund. Much of the institutional structure of current financial institutions and markets is likely to be changed in response to the global financial crisis that began in 2007. But what of the theory of Finance? Its usefulness is at risk too, we contend. The challenge brought by the Behavioral literature has proven a credible threat to the theory by presenting evidence that. investors may not always be rational. But of far more importance than investor rationality is investor belief that they can safely invest their funds based on the information found in financial reports provided by insiders. At a minimum, as Fama and French argue, imitation The author would like to thank the anonymous referee, Edward Kane, Graham Partington and attendees at the French Financial Association Meetings and the Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand Meetings. 1 6/29/2017 of the average investor should not lead investors astray. Holding the market index should provide an adequate reward for risk, given sufficient time. Has the crisis has rendered this belief a dubious proposition? This paper shows that faith in the information provided by insiders is subject to more doubt in some circumstances than others and that long term credibility of insiders is testable by investors. This should salvage the threat to the theory and replace it with a means for investors to evaluate the integrity of the markets they use. It should also present regulatory policies more conducive to broad portfolios carrying a maximal return for the risk implied. Perhaps the most important proposition in the theory of investment is the Capital Asset Pricing Model of Sharpe and others. This model assumes that all investors have equal information. If so, a portfolio containing the entire market portfolio should be the best investment for the average investor on an ex ante basis. However, as Roll () points out, the CAPM is therefore not testable – this equal information assumption being manifestly counter to fact. In what follows we will make a transition from the benign, investor-friendly market environment of Fama-French (2006) to the more chaotic, investor-unfriendly market of Kane (2004, 2000). In Kane’s model passivity is a costly mistake. We show that the Kane results depend not on a different theory, but upon a difference in the process by which inside information is shaped. In the following empirical analysis, we produce market-based evidence that that both Fama-French and Kane markets exist and are both consistent with the “liberalized economy” tag that has become the global standard. 2 6/29/2017 The article proceeds as follows. Initially we show that the Fama-French (2006) conclusion that investor passivity leads to portfolio optimality assumes insider passivity as well as outsider passivity. We then show that Kane’s introduction of the possibility of insider active provision of misleading misinformation reverses the optimality of outsider passive investment. The article then raises the empirical question: “Is there evidence that some countries are characterized primarily by lack of information and others by misinformation?” The answer is partially provided in the empirical literature, which considers insider effects on investment performance in various liberalized markets. Using stock return data from Germany, Mexico, Thailand, Turkey and the United States, we investigate the portfolio efficiency of passivity. In what countries is holding a market portfolio of common stocks prudent? Is the market index portfolio on the efficient portfolio frontier? The test allows us to reject the hypothesis that passive investment is efficient in Mexico, Turkey and Thailand. In Germany and the United States the results are less clear, but efficiency cannot be rejected. 2 2.1 Information and Investor Classes. The Fama-French Version. Fama-French (2006) initially identifies two investor classes: noise investors and full information investors. The root issue this permits them to examine is the cost of being an outsider. There is a body of empirical evidence to the effect that inside information is different and better than outside information – in the sense that insiders tend to invest in portfolios that produce higher returns than those of outsiders, which makes this issue an important one. 3 6/29/2017 So it is necessary in Fama-French (2006) that insider and outsider information sets are different. This is simply a reasonable working definition of the difference between insider and outsider. However, there are two possible ways to drive a wedge between insider and outsider portfolios: a change in the information possessed by insiders or a change in the malicious information possessed by outsiders. Any material difference between inside and outside information will improve the lot of insiders and may result in outsider portfolio inefficiencies by the definition of the two classes. Any difference between the inside and outside information sets that affects relative returns or risks produces differing portfolio choices. Insider holdings then change relative to outsider holdings in a way that directly benefits insiders, producing the situation characterized by Figure 1 from Fama-French. (Figure 1) Once the initial conditions of Figure 1 are established, the Fama-French conclusions follow. Following Fama-French, point T on the graph is the optimal portfolio from an ex ante risk and return point of view. D is the average portfolio held by outside investors. Since the classes hold different portfolios, neither class holds the market portfolio, represented by M in Figure 1. Subsequent adjustment to efficiency is straightforward. By implication of the decision to invest in the entire market, outsiders choose a new average portfolio that includes more of T. However, although the new outsider average portfolio is the average of D and T, when the market clears passive investors do not hold M as planned. Inside investors in T do not change their holdings, and thus the average of D and T is still not M. Outsiders again rebalance their holdings in period t 1 , expecting to hold the market portfolio. The result 4 6/29/2017 is still closer to T, but not T or M. But in the limit as t goes to infinity, D, M and T are identical. However Fama-French (2006) uses an unnecessary and ultimately distracting device to produce the initial condition of outsider portfolio inefficiency. In Fama-French noise investors irrationally collect information that generates risk and return estimates that have no forecasting merit. As a result these noise investors choose, on average, an inefficient portfolio. Fama-French then ask what effect a more rational decision on the part of outside investors, to buy the market portfolio, would have on their portfolio performance. It is the subsequent adjustment to optimality resulting from this passive investment strategy that is the primary focus of Fama-French, not the question of how investors come to hold initial inefficient portfolios. But it matters greatly how outsiders come to hold an inefficient portfolio. In fact the original source of inefficiency is the key distinction between FamaFrench and Kane, not the subsequent adjustment to equilibrium. And the Fama-French “noise” approach that produced Figure 1 initial conditions begs a pair of questions. First, the Fama-French noise assumption relies on investor irrationality. However, economists prefer not to rely on investor irrationality to explain behavior, because irrationality can be used to explain any behavior. If such an assumption is unnecessary, it would be best to avoid it. The noise hypothesis also begs a second question: What noise? Even noise has a production cost and requires a profit motive. No explanation is provided. Importantly, the noise of Fama-French is unnecessary to produce the important Fama-French result. There are more reasonable ways to produce the initial conditions of Fama-French analysis. 5 6/29/2017 We suggest that it is both more consistent with the norms of economic analysis and also an appropriate use of Ockham’s razor to simply assume an exogenous change in inside information and allow outsiders to rationally choose the market portfolio from the outset. Rather than outsiders beginning with more misinformation than insiders, coming from some unknown source, we assume that insiders begin with more good information than outsiders. As we demonstrate, this change does no violence to the Fama-French analysis or results. However it does put the focus of attention directly on insider disclosure and thus draws attention to the key difference between Fama and French assumptions and those of Kane. What matters is not the adjustment from Fama-French Figure 1 to outsider efficiency in period t. That process is identical in Fama-French and Kane. The aspect of the market adjustment process that drives the optimality of investor passivity is the process by which the inefficient portfolio, D, of outsiders comes about in the previous period, t 1. To see why the t-period adjustment in Fama-French is beside the point, we move to the earlier period, t 2 . We drop the noise assumption and assume both insiders and outsiders hold the market portfolio from the beginning. Thus all investors hold the same optimal portfolio initially. But there are separate reasons for holding it. Outsiders hold it because it is the market portfolio, M. Insiders hold it because they know it is the efficient portfolio, T. Then we permit a change in the inside information set in period t 1. We will assume an exogenous change in technology, resulting in an increase in wealth through an expansion of the production possibility frontier. If relative prices do not change, there is no adjustment. Insider’s wealth rises, but so does that of outsiders in equal proportion. Portfolios all 6 6/29/2017 remain at T. However, if relative risks or returns change, insiders trade to capture the benefits of a new efficient portfolio on a new efficient frontier. Outsider’s portfolio becomes inefficient and different from the portfolio of insiders, creating the conditions of Fama-French Figure 1. The adjustments from there follow Fama-French, with both outsiders and insiders holding the efficient portfolio in the limit as before. Thus the reassuring implications of Fama-French adjustment for outsider portfolio management are consistent with no loss of wealth by outsiders as well, in the case where inside information is changed exogenously – that is, where outsiders are uninformed, not misinformed. 2.2 The Kane Version. How does misinformation lead to Kane’s results? The simplest example of which we can conceive follows. It is suggestive of the structure of the other counterexamples characterized by Kane and of a different process by which intra-period information is generated. As before, equilibrium prevails in period t 2 . To generate Kane results, insiders generate misinformation. For example, suppose that one asset, A, worth PA A in the market portfolio, is controlled by insiders who incorporate and issue claims on 100% of A, which replace A in the market portfolio. Under Modigliani and Miller (1958) assumptions, the claims are also worth PA A . The manager then absconds with the real asset A, forming a second corporation, Firm A , with no apparent assets but in fact in control of the rights to A. The salient fact is that the value of assets is concealed from the market. Thus there is misinformation. Insiders take possession of the claims on A . Claims on A have zero market value, since only insiders know Company A is in control of the former assets A. Returning to Fama-French’s Figure 7 6/29/2017 1, T is now the insider’s portfolio, containing only A since the returns to A are initially infinite. If we assume insiders consume some of the proceeds of A , then A must produce returns and will have a non-zero market value, driving a wedge between outsider portfolios and the market portfolio as before. The model once again meets the conditions of Figure 1. The analysis of convergence to efficiency is that supporting Fama-French Figure 1 as before. However, outsiders have lost wealth of value PA A to insiders, with no change in the real assets on the optimal point of the efficient frontier. This simple misinformation example readily extends to include all cases that fit the characteristics of purposeful misinformation as characterized in the following from Kane, 2004: “Financial information may be deemed perfectly true and timely only if it conforms to all relevant facts that are knowable at a given time. Disinformation consists of false and half-true statements or opinions that interested parties convince others to take seriously. Its message is designed to be negatively correlated with unfavorable information that insiders manage to withhold from outsiders and sometimes (through the psychological mechanism of denial) even from themselves. Financial disinformation relies on deceptive reports and misleading claims about upside and downside risks. The spurious elements or false implications of these claims are shaped for the express purpose of preventing outside counterparties from grasping the full-information or ‘inside’ risks inherent in holding a particular class of assets.” The unifying characteristic of Kane’s different forms of misinformation is that each involves convincing the average dollar investor of real asset values counter to fact. 8 6/29/2017 Kane assumes information changes are endogenous. Insiders do not learn new information, they generate misinformation. Thus the change in information is such that insiders do not change their holdings. Instead they mislead outsiders, resulting in an unanticipated change in the real assets held by outsiders. There is no expansion in the production possibility frontier, but instead an unintended shift in outsider holdings to inefficient portfolios interior to the unchanged efficient portfolio frontier. Thus this misinformation returns investors to Fama-French Figure 1, because misinformation creates differences among insider and outsider holdings. The subsequent adjustment process is identical to that of Fama-French. The important distinction is that the “learned” exogenous information of the first FamaFrench example increases the wealth of both investor classes; the “created” endogenous information of the second example due to Kane results in a shift in the share of the unchanged total stock of investor wealth from outsiders to insiders in period t . Since the Kane information generation process is endogenous, a choice by insiders that works in their favor, rationally there will be further endogenous changes with the limiting result that passively investing outsiders’ share of total wealth will be zero. Thus the convergence to efficiency of outsider market portfolios in CAPM models permitting different information sets is not guaranteed. Outcomes depend upon whether inside information is generated endogenously or exogenously. 3 Evidence of Investor Disinformation around the Globe. Recent literature has produced substantive evidence that Mexico, Thailand and Turkey, among other markets that were liberalized before the early 1990’s, are in some respects inefficient in allowing market forces to allocate capital to its most productive uses (c.f. 9 6/29/2017 Harvey and Bekaert (2000) for a short rationale for the “liberalized” designation of the three markets.) In these three countries, market liberalization and conversion to capitalism may have been to a degree self-serving ventures of the elite that have caused some damage to less informed investors. This possibility is developed in emerging markets literature examining financial market impact of insider decision-making by several authors. For example, Bhattacharya and Daouk (2002, 2005) identify costs associated with lack of enforcement of insider trading laws in various countries. Peek and Rosengren (2001) detail the effects of fraudulent bank lending practices in Japan. Dyck and Zyngales (2004) present evidence of substantial premiums for corporate control relative to simple share ownership, for which evidence exists in Mexico, Thailand and Turkey among other emerging markets. The experience in these countries stands in contrast to the corporate/government nexus in Germany. Germany is more directly comparable to emerging markets such as Mexico, Thailand and Turkey than might be thought, due to the German tribulations related to the absorption of formerly Communist East Germany. Dyck (1997) provides a detailed insight into East Germany’s transition from a control economy to a market economy. While he indicates that the experience was expensive, fraught with conflict, and characterized by setbacks; he argues that it was on the whole the most successful of the Eastern European privatization efforts. However, the articles considered leave open the critical question raised by Fama-French and Kane; whether and how market forces might counteract the observed effects of the agency problems the authors identify. They do not tell us whether investors discount the 10 6/29/2017 prices of associated securities, leaving post-adjustment returns consistent with risk assumed. In addition, the articles focus on specific aspects of the general phenomenon of market dissimulation. In this sense, they may be thought of as components of a “bottomup” construction of the costs of insider duplicity. Although this article is consistent with these other earlier articles, it considers the cost of corruption identified from the investor side of the equation, through investors’ rational pursuit of misinformation-inspired economic rents, a “top-down” approach to estimating part of the cost of insider misinformation. An alternative theoretical top-down discussion of conditions under which market forces are consistent with sustained asset stripping is provided by Hoff and Stiglitz (2005) with a focus on the interaction between privatization and the rule of law in the countries of the former Soviet Bloc – Russia especially. 4 4.1 Empirical Results. The Data. The data series used in this study were stock indexes constructed by Datastar and interest rates provided through DataStar by the country being studied. In each country the series in question were monthly returns calculated from each index from the earliest date for which there is available data to the end of 2006, with the exception of the United States, where 20 years of data ending in 2006 was used. Table 1 lists the series used for each country and the time period over which returns were measured. Each return series was the return in the home country currency, since currency translation has no effect on efficiency of investments as long as performance is measured in a single currency. Table 1 11 6/29/2017 4.2 The Test. We use a simple Markowitz model. The Markowitz model specifies rt et with et ~ N (0.) (1) Where rt is the vector of returns to each initial portfolio of investments, is the vector of expected returns to the portfolios, is the covariance matrix of the expected returns, and et is the vector of errors in meeting expected returns. The efficient portfolio frontier is then constructed from the estimated covariance and correlation matrix and mean returns equal to the sample means of the chosen time series of returns in each country, based on the algebraic technique of Huang and Litzenberger,1988, as implemented for example in Jackson,2001. The test compares the simple mean and variance of the index portfolio of each country as defined by DataStar with an efficient portfolio frontier constructed from the index portfolio, three other industry index portfolios, and a single short term interest rate series. We reject the hypothesis that the country allocates private resources efficiently if the market index portfolio does not produce a higher return than the minimum risk portfolio of the market in question. In other words, if minimizing risk using the county’s least risky Treasury securities outperforms passive investment in an index portfolio in a given country, that country fails to reward passive investment. In a Fama-French (2006) financial market, the market index portfolio would tend to pass this test. In the markets of Kane, failing such a test is imaginable. The results appear in Figures Two through Six. As the figures display, Mexico, Thailand and Turkey fail the test, but in Germany and the United States, efficiency cannot be rejected. 12 6/29/2017 This analysis suffers from at least two shortcomings. First, we pick only five investments in each country. The CAPM is a theory of all available portfolios. The effect of this shortcoming is, however, predictable. By including more portfolios, the efficient portfolio frontier is inevitably expanded, and individual portfolios will all be found less efficient. Thus the rejection of passive investment as an attractive alternative in Mexico, Thailand, and Turkey is robust to this problem, but doubt is raised about the efficiency of the index portfolios of Germany and the United States. A second problem is less tractable. The covariance matrix of portfolio returns in our investment universe are nearly singular, and as a result there is substantial round-off error in the estimated values of the efficient frontier, which depend on the values of the inverse of a near-singular matrix with predictably large round-off errors. This flaw is apparent in Figure 6, as the index portfolio, one of the portfolios used to construct the efficient portfolio frontier, cannot actually be outside the efficient portfolio frontier as the diagram suggests. But this is not simply a problem faced by econometricians. It is also a problem faced by investors. If portfolios available to investors are not statistically different, investors cannot be expected to choose among them wisely. In the end, we must be skeptical about the ability of investors to choose “the” efficient portfolio, but we are free to conclude that passive investment was unsuccessful in Mexico, Thailand and Turkey. Both these qualifications tend to suggest that while one may find it difficult to find the efficient portfolio in a Fama-French economy, it is not so difficult to distinguish between economies that are misinformed in the main or uninformed in the main. 13 6/29/2017 Significance of Country Inefficiencies: If the statistical significance of the efficiency of the countries’ index portfolios is measured by a simple t-statistic, with the numerator the return of the market portfolio less the return of the efficient portfolio of the same variance, significance can be identified by inspection of the Charts. Since the returns for Mexico, Thailand and Turkey are actually less than the minimum variance returns, the t-statistics of these countries show significant inefficiencies. Germany, as stated above, is indeterminate. In the United States cannot be rejected as round-off error produces a t above zero, statistically impossible, indicating super-efficiency due to round-off error. 5 Conclusions. Two versions of a model of investor difference of opinion are constructed. In this model investors trade rationally but are either misinformed or uninformed. A Fama and French 2006 version assumes insiders provide no information; a Kane version assumes misinformation. In the case of insider secrecy, passive investment leads to investor optimality in the limit. In the case where misinformation is the rule, passive investors ultimately are left with nothing. The behavior of actual returns in five markets – Germany, Mexico, Thailand, Turkey and the United States – is examined. We reject the efficiency of passive investment in Mexico, Thailand and Turkey but not in Germany and the United States. Why did the index portfolio perform so poorly in the three countries? If investors believe they are better off if they do not consider alternatives to CAPM, they might ignore evidence of the inefficiency of CAPM over substantial periods of time. Little would be lost by them in a Fama-French world. In the Kane version, if most investors are similarly 14 6/29/2017 credulous, accepting the textbook version of CAPM, and unwilling to pay the costs of obtaining full information, a window of opportunity exists in which insiders can exploit outsiders. Thus our empirical results are evidence of insider duplicity in the presence of sustained naïve investment despite substantial losses in the three countries. There are alternatives to investor lassitude in explaining the failure of CAPM in these countries. The author’s other work on banking agency problems in Mexico, Thailand and Turkey suggests that outsider acceptance of poor returns in the financial sector may be in large part involuntary as governments permit insider-controlled banks to invade the tax base, using the proceeds to cover insider losses. These results raise a few interesting questions: 1. How should foreign investors measure risk and return in these countries? Should they be seeking to hold a diversified international portfolio including securities issued in duplicitous markets? How should we characterize the risk/return alternatives available to foreign investors? If these conditions are common in other countries, conclusions based on risk/return comparisons of representative international composite stock indices are overturned. Local country bias may be outsider wisdom. 2. Most intriguing is the possibility that by encouraging investor adoption of the assumptions of Neoclassical Finance embodied in CAPM and its implementation, Finance specialists may be invalidating the theory. A financial system composed of an excess of model-mimicking zombies may result, thereby making a continuation of the unremitting series of financial scandals of the past twenty years easier and more profitable. This is an example of a familiar econometric problem. Just as adoption of 15 6/29/2017 monetary growth rules may have weakened the relationship between measures of GDP and money in macroeconomic analysis, rule-based investing may have weakened the relationship between market portfolio returns and individual stock returns in much the same way. 16 6/29/2017 Bibliography Author, 2006. Financial Market Evidence of Agency Problems in the Banking Systems of Mexico, Thailand, and Turkey, Working Paper, Griffith University. Bekaert, G., Campbell, H., 2000. Foreign Speculators and Emerging Equity Markets, Journal of Finance, 55, pp. 565--613. Bhattacharya, U., Daouk, H., 2002. The World Price of Insider Trading, Journal of Finance, 57, pp. 75--108. Bhattacharya, U., Daouk H., 2005. When No Law is Better Than a Good Law, http://ssrn.com/abstract=558021. Durnev, A., Nain, A., 2004. The Effectiveness of Insider Trading Regulation Around the Globe, William Davidson Institute Working Paper no. 695. Dyck, .J. A., 1997. Privatization in Eastern Germany: Management Selection and Economic Transition, American Economic Review, 87, pp. 565--597. Dyck, J. A., Zingales, L., 2004. Private Benefits of Control: An International Comparison, Journal of Finance, 59, pp. 533--596. Fama, E., 1970, Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work, Journal of Finance, 25, pp. 383—417. Fama, E., French, K., 2006. Disagreement, Taste and Asset Prices. Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming. 17 6/29/2017 ________________., 1992. The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns, Journal of Finance, 47, pp. 427—465. Hoff, K., Stiglitz, J. E., 2005. The Creation of the Rule of Law and the Legitimacy of Property Rights: The Political and Economic Consequences of a Corrupt Privatization, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3779. Huang, C., Litzenberger, R., 1988, Foundations for Financial Economics, North Holland, New York Kane, E., 2005. Charles Kindleberger: An Impressionist in a Minimalist World, Atlantic Economic Journal, vol. 33. March, 35-42. _______, 2000, The Dialectical Role of Information and Disinformation in Banking Crises, Pacific Basin Finance Journal, vol. 8, July, pp. 285--308. Markowitz, H. M., 1952. Portfolio Selection, Journal of Finance, 7, pp.77--91. Peek, J., Rosengren, E. S., 2001. Determinants of the Japan Premium: Actions Speak Louder Than Words, Journal of International Economics, 53, pp. 285-305. Sharpe, W. F., 1964. Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of Market Equilibrium under Conditions of Risk, Journal of Finance, 19, pp. 425—442. 18 6/29/2017 Figures 19 6/29/2017 Table 1 – Time Series, Monthly Stock Indexes and Interest Rates Period Beginning Index 1/01/1973 Germany - DS Industrials Germany - DS Construction and Materials Germany - DS Banks Germany - DS Market Germany - Overnight Mexico 8/19/1992 Mexico - DS Banks Mexico - DS Retail Mexico - DS Telecom Mexico - DS Index Mexico - Commercial Paper Thailand 9/25/1993 Thailand - DS Hotels Thailand - DS Telecom Thailand - DS Banks Thailand - DS Index Thailand - Repo Turkey - DS Construction Turkey 4/30/1994 and Materials Turkey - DS Diversified Industrials Turkey - DS Banks Turkey - DS Index Turkey - Repo United States 8/31/1987 US - DS Pharmaceuticals US - DS Oil and Gas US - DS Computer Services US - DS Index US - Fed Funds Country Germany 20 6/29/2017 Figure 2 Investment Opportunities and Portfolios, Thailand Efficient Portfolio Frontier 20% 15% Market Portfolio 10% 5% 0% 0.0% -5% Minimum Risk Return 0.5% 1.0% 1.5% 2.0% 2.5% -10% -15% 21 6/29/2017 Figure 3 Investment Opportunities and Portfolios, Turkey 80% Efficient Portfolio Frontier Market Portfolio 70% 60% 50% 40% Minimum Risk Return 30% 20% 10% 0% 0% 200% 400% 600% 22 800% 1000% 6/29/2017 Figure 4 Investment Opportunities and Portfolios, Mexico 80% 60% Efficient Portfolio Frontier 40% Market Portfolio 20% Minimum Risk Return 0% 0% 100% 200% 300% 400% 500% 600% -20% -40% -60% 23 6/29/2017 Figure 5 Investment Opportunities and Portfolios, Germany 20% 15% Efficient Portfolio Frontier 10% Market Portfolio 5% Minimimum Risk Return 0% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% -5% -10% 24 6/29/2017 Figure 6 Investment Opportunities and Portfolios, United States 12% Efficient Portfolio Frontier 10% Market Portfolio 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% -50% 0% 50% 100% 25 150% 200% 6/29/2017 26 6/29/2017