* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Title - The E-Learning Experience

Alpine regiments of the Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Executive magistrates of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Roman architecture wikipedia , lookup

Conflict of the Orders wikipedia , lookup

Structural history of the Roman military wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Military of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Switzerland in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Demography of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Elections in the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

First secessio plebis wikipedia , lookup

Roman funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republican governors of Gaul wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Cursus honorum wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

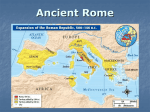

How was the society of the Roman Republic organized? How did it balance the dangers of internal division and external attack? In 509 B.C.E., the Roman Republic was established following the overthrow of the previously ruling monarchy. A republican form of government was favoured by the Roman nobles who sought to maintain their positions of power. The transformation of Rome’s government from monarchy to republic was not an easy transition. However, the change in the style of government marked a turning point in Roman civilization. During its five centuries under republican rule, Rome would successfully expand its empire to encompass the entire Mediterranean Sea. In order to rule this great empire effectively, the Romans created a system of alliance, enabling them to control the risks of internal division and the inevitable threat from external attack. The Roman Republic was ruled primarily by its magistrates. The chief magistrates of the Roman Republic were the two consuls.1 Chosen annually, the consuls were responsible for the government of Rome and leading Rome’s armies into battle. In 366 B.C.E., the office of praetor was created and charged with authority over civil law. Additionally, when the consuls were not present, the praetor was given the authority to govern Rome and lead its armies into battle. The expansion of Rome’s territory led to the addition of a second praetor, who was responsible for judging cases involving noncitizens. As Rome began to acquire foreign provinces, new praetorships were created, and by the end of the republic there were eight in all.2 Other administrative officials within the Roman state held specialized obligations, including the administration of financial affairs and the supervision of the public games of Rome.3 The Roman senate, or council of elders, held a particularly important place within the government of the republic. The senate consisted of a select group of up to three hundred powerful men who were obligated by law to serve for life. Although the senate was tasked simply with advising the magistrates, the caliber of the senate meant the advice given was never taken 1 G Woolf, The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Roman World, Cambridge, 2003, pp. 30 ibid., p.31. 3 WJ Duiker and JJ Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, Third Edition, California, 2008, pp. 100 2 lightly. In effect, all government was in the hands of a close circle of aristocrats whose stronghold was in the senate.4 In addition to the senate, the Roman Republic consisted of a number of popular assemblies, the most important of these being the centuriate assembly. The centuriate assembly was organized according to a class system based on wealth and was structured so as to maintain a constant majority for the wealthiest citizens. Another popular, albeit insignificant assembly in terms of power and authority, was created in 471 B.C.E., and was known as the council of the plebs. The creation of this assembly was the result of a struggle that arose at the beginning of the fifth century B.C.E. between Rome’s two distinct groups or classes, the patricians and the plebeians. This struggle, known as the struggle of the orders, would last nearly the entire republican era. Of Rome’s two distinct classes the patricians constituted the highest class of society, the aristocratic governing class. Only this group of great landowners could become consuls, magistrates and senators. The plebeians were a considerably larger group consisting of nonpatrician large landowners, less wealthy landowners, artisans, merchants and small farmers.5 Although plebeians as well as patricians were citizens, plebeians did not share the same rights as their considerably wealthier and powerful compatriots. The two classes, patrician and plebeian, were so sharply defined that they were practically separate communities; plebeians, for instance, could not marry into the patrician class and could not hold any important office.6 As a result of such discriminations, the plebeians sought both political and social equality with the patricians7 and the struggle of the orders ensued. The first breakthrough in the plebeians’ struggle was the creation of the Tribunate of the Plebes early in the fifth century B.C.E.8 The tribunes were empowered to protect plebeians against arrest by patrician magistrates.9 A new law was passed permitting intermarriage between patricians and plebeians and in the fourth century B.C.E., plebeians claimed the right to be elected as 4 JC Stobart, The Grandeur that was Rome, 4th edition, New York, 1961, pp.63 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 100 6 M Hadas, GREAT AGES OF MAN, A History of the World’s Cultures, Imperial Rome, Nederland, 1966, pp. 36 7 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 100 8 Hadas, Imperial Rome, pp. 36 9 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 100 5 consuls. After two centuries of struggle the plebs had thus obtained all their objectives and that with a minimum of violence and through due process of law.10 All Roman citizens were equal under the law and could claim social and political equality by 287 B.C.E. However, as a result of strategic marriages, now allowable under the law between patricians and plebeians, families formed alliances producing a new senatorial aristocracy that came to dominate Rome politically.11 Along with these organizations of the Roman Republic and its society, came the development of a powerful and effective military network. The Romans valued military success, and from the start of the republic they engaged in a series of wars that conquered first Latium and then all of Italy.12 In 304 B.C.E., the Roman army was successful in defeating its Latin enemies in Latium. With Latium firmly under control, the Romans embarked on a series of campaigns that ultimately brought all of Italy under their domination.13 Throughout the next half century, Rome waged a triumphant battle with the hill peoples from central Italy. Following their victorious struggle the Roman army came into direct contact with the Greeks and after nearly eighty years of warfare, in 267 B.C.E., the Romans had successfully completed their conquest for southern Italy with their defeat of the Greek cities.14 The Etruscans, from Etruria in the north of the Italian peninsula were the next to experience defeat at the hands of the powerful Roman army. After crushing the remaining Etruscan states to the north in 264 B.C.E., Rome had conquered most of Italy.15 It should be remembered that throughout the Roman Republic the soldiers fighting for Rome were her own citizens for whom defence of the state was a duty, a responsibility and a privilege.16 With the size of its empire increasing, Rome would need to create a system allowing it to protect itself against internal division. Keeping control of their captured lands and to subdue the inhabitants, the Roman Confederation was established. Under the confederation, Rome allowed some peoples – especially the Latins – to have full Roman citizenship. Most of the remaining 10 DR Dudley, The Civilisation of Rome, New York, 1962, pp.37 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 100 12 Woolf, Roman World, pp.34 13 Woolf, Roman World, pp.34 14 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 99 15 Ibid. 16 L Keppie, The Making of the Roman Army: From Republic to Empire, London 1998, pp. 17 11 communities were made allies.17 The grant of citizenship to the allied communities now qualified the Latins and Italians for service in the legions.18 Nearly all of Rome’s allied cities were granted municipal status; however they were not allowed the right to vote and were prohibited from exercising these rights with one another. Failure to comply with these laws resulted in a tax penalty which had to be paid to Rome. The Romans made it clear that loyal allies could improve their status and have hope of becoming Roman citizens.19 Through this gesture, the Romans had found a way to give conquered peoples a stake in Rome’s success.20 Roman success in their conquest of Italy was primarily due to their consistent policies and their excellent sense of strategy which not only aided them in repressing mutiny, but also allowed them to successfully thwart attempted attack from foreign enemies. As they conquered, the Romans established colonies21 of veteran soldiers at strategic locations throughout Italy22. These colonists retained their Roman citizenship and enjoyed home rule; in return for the land they had been given, they served as a kind of permanent garrison to deter or suppress rebellion.23 The Romans then built a series of roads to each of these colonies and by connecting them they had created an effective network enabling them to mobilize Italy’s entire military manpower. This network system guaranteed a Roman army could quickly reinforce an embattled colony or put down any uprising. Both the colonies, communication network and military roads help explain the reluctance to revolt by internal as well as external forces.24 The Romans maintained the same strategies used to conquer Italy to conquer the Mediterranean. Rome faced some formidable foes and suffered some heavy losses but its policy of forming alliances with those conquered meant it had the numbers necessary to build up its army internally as well as use alliances formed outside of Italy. Rome with its 17 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History, pp. 99 P Southern, The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History, Oxford, 2007, pp. 95 19 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History, pp. 99 20 Ibid. 21 Ibid. 22 ibid. 23 D Kagan, S Ozment, FM Turner, The Western Heritage, Eighth Edition, Volume One: to 1740, New Jersey, 2004, pp. 118 24 ibid. 18 structured governing body was able to successfully adapt its military to meet challenges it faced and to then use its strengths to dominate opponents. The Roman society was structured and organized in such a way as to allow class division and inequality particularly in the political scene. This organization however divisive, did promote during this time, strength in the government and therefore strength in the military. This strength resulted in the successful ordering of its people and the conquering of not only the whole of Italy but much of the Mediterranean. Rome seemed to find that after a conquest, instead of dominating the conquered area, the formation of alliances and the granting of certain rights to the conquered people along with its existing ruling policies was enough to ensure the loyalties it desired. The Roman republic government consisted of superb diplomats’25 who made correct decisions based on strategy in order to maintain dominance. These strategies did not only involve the military but also dealt with social problems. This can be seen in the granting of rights to its underclass people giving the illusion of equality but in reality maintaining power among those who successfully sought for it and maintained it through the organization of the law and the military. 25 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 99 BIBLIOGRAPHY Dudley DR, The Civilization of Rome, The New American Library, Inc., 1962 Duiker WJ and Spielvogel JJ, The Essential World History to 1500, Third Edition, Thomas Higher Education, California, 2008 Hadas M, GREAT AGES OF MAN, A History of the World’s Cultures, Imperial Rome, Time Inc., Nederland, 1966 Kagan D, Ozment S, Turner FM, The Western Heritage, Eighth edition, Volume One: to 1740, Pearson Education, 2004 Keppie L, The Making of the Roman Army: From Republic to Empire, Routledge, London, 1998 Southern P, The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History, Oxford University Press, USA, 2007 Stobart JC, The Grandeur that was Rome, St. Martins Press, New York, 1961 Woolf G, The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Roman World, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003