* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download weiten6_PPT06

Learning theory (education) wikipedia , lookup

Applied behavior analysis wikipedia , lookup

Insufficient justification wikipedia , lookup

Verbal Behavior wikipedia , lookup

Adherence management coaching wikipedia , lookup

Behavior analysis of child development wikipedia , lookup

Psychophysics wikipedia , lookup

Psychological behaviorism wikipedia , lookup

Behaviorism wikipedia , lookup

Eyeblink conditioning wikipedia , lookup

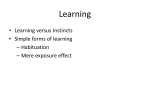

Chapter 6 Learning Classical conditioning Ivan Pavlov Terminology – – – – Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS) Conditioned Stimulus (CS) Unconditioned Response (UCR) Conditioned Response (CR) Table of Contents Fig 6.1 – Classical conditioning apparatus. An experimental arrangement similar to the one depicted here (taken from Yerkes & Morgulis, 1909) has typically been used in demonstrations of classical conditioning, although Pavlov’s original setup (see inset) was quite a bit simpler. The dog is restrained in a harness. A tone is used as the conditioned stimulus (CS), and the presentation of meat powder is used as the unconditioned stimulus (UCS). The tube inserted into the dog’s salivary gland allows precise measurement of its salivation response. The pen and rotating drum of paper on the left are used to maintain a continuous record of salivary flow. (Inset) The less elaborate setup that Pavlov originally used to collect saliva Table of Contents on each trial is shown here (Goodwin, 1991). Fig 6.2 – The sequence of events in classical conditioning. (a) Moving downward, this series of three panels outlines the sequence of events in classical conditioning, using Pavlov’s original demonstration as an example. Table of Contents Fig 6.3 – Classical conditioning of a fear response. Many emotional responses that would otherwise be puzzling can be explained by classical conditioning. In the case of one woman’s bridge phobia, the fear originally elicited by her father’s scare tactics became a conditioned response to the stimulus of bridges. Table of Contents Classical Conditioning: More Terminology Trial = pairing of UCS and CS Acquisition = initial stage in learning Stimulus contiguity = occurring together in time and space 3 types of Classical Conditioning – Simultaneous conditioning: CS and UCS begin and end together – Short-delayed conditioning: CS begins just before the UCS, end together – Trace conditioning: CS begins and ends before UCS is presented Table of Contents Processes in Classical Conditioning Extinction Spontaneous Recovery Stimulus Generalization Discrimination Higher-order conditioning Table of Contents Fig 6.9 – Acquisition, extinction, and spontaneous recovery. During acquisition, the strength of the dog’s conditioned response (measured by the amount of salivation) increases rapidly and then levels off near its maximum. During extinction, the CR declines erratically until it’s extinguished. After a “rest” period in which the dog is not exposed to the CS, a spontaneous recovery occurs, and the CS once again elicits a (weakened) CR. Repeated presentations of the CS alone re-extinguish the CR, but after Table of Contents another “rest” interval, a weaker spontaneous recovery occurs. Fig 6.10 – The conditioning of Little Albert. The diagram shows how Little Albert’s fear response to a white rat was established. Albert’s fear response to other white, furry objects illustrates generalization. Table of Contents Fig 6.12 – Higher-order conditioning. Higher-order conditioning is a two-phase process. In the first phase, a neutral stimulus (such as a tone) is paired with an unconditioned stimulus (such as meat powder) until it becomes a conditioned stimulus that elicits the response originally evoked by the UCS (such as salivation). In the second phase, another neutral stimulus (such as a red light) is paired with the previously established CS, so that it also acquires the capacity to elicit the response originally evoked by the UCS. Table of Contents Operant Conditioning or Instrumental Learning Edward L. Thorndike (1913) – the law of effect B.F. Skinner (1953) – principle of reinforcement – – – – Operant chamber Emission of response Reinforcement contingencies Cumulative recorder Table of Contents Fig 6.14 – Reinforcement in operant conditioning. According to Skinner, reinforcement occurs when a response is followed by rewarding consequences and the organism’s tendency to make the response increases. The two examples diagrammed here illustrate the basic premise of operant conditioning—that voluntary behavior is controlled by its consequences. These examples involve positive reinforcement (for a comparison of positive and negative reinforcement, see Figure 6.21). Table of Contents Fig 6.15 – Skinner box and cumulative recorder. (a) This diagram highlights some of the key features of an operant chamber, or Skinner box. In this apparatus designed for rats, the response under study is lever pressing. Food pellets, which may serve as reinforcers, are delivered into the food cup on the right. The speaker and light permit manipulations of visual and auditory stimuli, and the electric grid gives the experimenter control over aversive consequences (shock) in the box. (b) A cumulative recorder connected to the box keeps a continuous record of responses and reinforcements. Each lever press moves the pen up a step, and each reinforcement is marked with a slash. Table of Contents Basic Processes in Operant Conditioning Acquisition Shaping Extinction Stimulus Control – Generalization – Discrimination Table of Contents Fig 6.16 – A graphic portrayal of operant responding. The results of operant conditioning are often summarized in a graph of cumulative responses over time. The insets magnify small segments of the curve to show how an increasing response rate yields a progressively steeper slope (bottom); a high, steady response rate yields a steep, stable slope (middle); and a decreasing response rate yields a progressively flatter slope (top). Table of Contents Table of Contents Reinforcement: Consequences that Strengthen Responses Delayed Reinforcement – Longer delay, slower conditioning Primary Reinforcers – Satisfy biological needs Secondary Reinforcers – Conditioned reinforcement Table of Contents Schedules of Reinforcement Continuous reinforcement Intermittent (partial) reinforcement Ratio schedules – Fixed – Variable Interval schedules – Fixed – Variable Table of Contents Fig 6.19 – Schedules of reinforcement and patterns of response. Each type of reinforcement schedule tends to generate a characteristic pattern of responding. In general, ratio schedules tend to produce more rapid responding than interval schedules (note the steep slopes of the FR and VR curves). In comparison to fixed schedules, variable schedules tend to yield steadier Table of Contents responding (note the smoother lines for the VR and VI schedules on the right) and greater resistance to extinction. Consequences: Reinforcement and Punishment Increasing a response: – Positive reinforcement = response followed by rewarding stimulus – Negative reinforcement = response followed by removal of an aversive stimulus • Escape learning • Avoidance learning Decreasing a response: – Punishment – Problems with punishment Table of Contents Fig 6.21 – Positive reinforcement versus negative reinforcement. In positive reinforcement, a response leads to the presentation of a rewarding stimulus. In negative reinforcement, a response leads to the removal of an aversive stimulus. Both types of reinforcement involve favorable consequences and both have the same effect on behavior: The organism’s tendency to emit the reinforced response is strengthened. Table of Contents Fig 6.22 – Escape and avoidance learning. (a) Escape and avoidance learning are often studied with a shuttle box like that shown here. Warning signals, shock, and the animal’s ability to flee from one compartment to another can be controlled by the experimenter. (b) According to Mowrer’s two-process theory, avoidance begins because classical conditioning creates a conditioned fear that is elicited by the warning signal (panel 1). Avoidance continues because it is maintained by operant conditioning (panel 2). Specifically, the avoidance response is strengthened through negative reinforcement, since it leads to removal of the conditioned fear. Table of Contents Fig 6.23 – Comparison of negative reinforcement and punishment. Although punishment can occur when a response leads to the removal of a rewarding stimulus, it more typically involves the presentation of an aversive stimulus. Students often confuse punishment with negative reinforcement because they associate both with aversive stimuli. However, as this diagram shows, punishment and negative reinforcement represent opposite procedures Table of Contents that have opposite effects on behavior. Changes in Our Understanding of Conditioning Biological Constraints on Conditioning – Instinctive Drift – Conditioned Taste Aversion – Preparedness and Phobias Cognitive Influences on Conditioning – Signal relations – Response-outcome relations Evolutionary Perspectives on learning Table of Contents Fig 6.24 – Conditioned taste aversion. Taste aversions can be established through classical conditioning, as in the “sauce béarnaise syndrome.” However, as the text explains, taste aversions can be acquired in ways that seem to violate basic principles of classical conditioning. Table of Contents Observational Learning: Basic Processes Albert Bandura (1977, 1986) – Observational learning – Vicarious conditioning 4 key processes – – – – attention retention reproduction motivation acquisition vs. performance Table of Contents Fig 6.26 – Observational learning. In observational learning, an observer attends to and stores a mental representation of a model’s behavior (example: assertive bargaining) and its consequences (example: a good buy on a car). If the observer sees the modeled response lead to a favorable outcome, the observer’s tendency to emit the modeled response will be strengthened. Table of Contents