* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Atoms and quantum phenomena

Auger electron spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Marcus theory wikipedia , lookup

Mössbauer spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Molecular Hamiltonian wikipedia , lookup

Atomic orbital wikipedia , lookup

Degenerate matter wikipedia , lookup

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Eigenstate thermalization hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Rutherford backscattering spectrometry wikipedia , lookup

Electron configuration wikipedia , lookup

X-ray fluorescence wikipedia , lookup

Heat transfer physics wikipedia , lookup

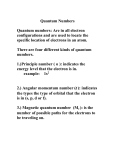

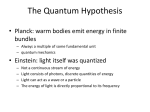

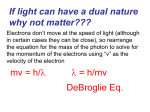

Atoms and quantum phenomena SASP 10th June 2010 Decay • 4 natural radioactive decay series • (starting with Thorium, Neptunium, Uranium, Actinium) • spontaneous nuclear reactions: mother, daughter, radiation emitted • (with time) all 4 series end at Pb (lead) [Pb is nice and stable] Relative amounts of isotopes can give information about age of objects Stability and the N-Z Graph • Darker isotopes shown here are stable. Radioisotopes are unstable. • As the proton number increases, an increasing ratio of neutrons is needed to form a stable nucleus A spot of history • Fission 1932: neutron discovered by Chadwick 1934 onwards: experiments done by Fermi et al in Rome - neutron irradiation of elements, starting with lightest & working through the periodic table up to Uranium. Expected transuranic elements. Hahn, Strassman, Lise Meitner repeat with U. 235 92 235 92 U n K Ba 3 n energy 1 92 141 1 0 36 56 0 U n Sr Xe 2 n energy 1 94 140 1 0 38 54 0 with a critical mass of U, neutrons emitted give a ‘chain reaction’ • Fusion small nuclei combine, releasing more energy than fission e.g. 2 1 H11H23 He energy Energy, mass and decay Let’s look at some numbers and see if they make sense. Mass of a proton = 1.673 x 10-27kg Mass of a neutron = 1.675 x 10-27kg Mass of a alpha particle (ppnn) = 6.643 x 10-27kg Energy, mass and decay Before we go on, kg is not the most helpful unit here so we are going to use u, the atomic mass unit wherever possible. 1u = 1/12 the mass of a neutral 12C atom (i.e. including its six electrons) 1u = 1.66056 x 10-27kg Mass of a proton = 1.007276u Mass of a neutron =1.008665u Mass of an electron = 0.000549u Mass of Hydrogen atom = 1.007825u Mass of Helium Atom = 4.002603 Mass of a alpha particle = 4.001505u Measurement interlude • Whilst we are at it, small amounts of energy mean that the Joule is a bit cumbersome. So we use the Electron Volt • Definition: The amount of kinetic energy gained by a single unbound electron when it accelerates through an electric potential difference of one volt. (Not SI, experimental) • 1eV = 1.602 x 10-19J Hmm, the sums don't add up ‘Missing mass’ and binding energy • The difference may not seem that much, but if you consider a helium atom (ppnnee) then we see that the atom is 0.03077u ‘too light’. Which is about 55 electrons. • In general all atoms are lighter than their constituent parts. In particular it is in the nucleus that this mass defect is particularly apparent. Somehow protons and neutrons are lighter inside the nucleus than outside. ‘Missing mass’ and binding energy • Protons and neutrons ejected from the nucleus regain their missing mass when they are outside the nucleus. The explanation for this comes with the idea of ‘binding energy’. • The mass defect (ΔM) of the nucleus is the difference between the total mass of all it's separate nucleons and the mass of the nucleus itself. • The binding energy of a nucleus (ΔE) is the energy released when the nucleus is assembled from its constituent nucleons. It is equal to the energy needed to separate the nucleus into individual nucleons. ‘Missing mass’ and binding energy • In the beginning, when the nuclei were created from the cosmic soup of fundamental particles, the strong nuclear force (that holds p and n together) had to do work to bring them together. The energy to do this work came from a direct conversion of mass to energy, which is why the assembled nucleus is lighter than the individual nucleons. [We tend to ignore electrons and comparatively they make a negligible contribution] ‘Missing mass’ and binding energy • In the nucleus, the nucleons are in a lower energy state. In order to separate the nucleus into it’s nucleons, an amount of work is needed to be done them. This amount of energy needed to pull them apart is equal to the work done to bring them together (by the strong force) in the first place. This energy is converted into matter, resorting the nucleons to their original masses. The Strong Force • The strong force (strong interaction) is observable in two areas: • Large scale – it binds protons and neutrons together to form the nucleus of an atom. • Smaller scale – it holds quarks and gluons together to form the proton, the neutron and other particles. So how do the mass and energy relate to each other? Binding energy • Clearly, there will be more ‘lost’ mass and more ‘gained’ energy per nucleon so the total binding energy in a nucleus is not a helpful number to give in order to give us a sense of how ‘stuck together’ a nucleus is. • This idea of how ‘stuck together’ it is, is important as it essentially tells us how stable the nucleus is and this stability idea (as mentioned earlier) is much more useful. Stability depend upon energy. • Binding energy per nucleon is more useful, average amount of glue per piece stuck together Binding energy per nucleon Same graph, other way up An even closer look (Some LOs) • explain atomic line spectra in terms of electron energy levels and a photon model of electromagnetic radiation • describe and explain the photoelectric effect, • solve quantitative problems using photon energy • be aware of the of the wave nature of electrons and calculate their wavelength Teaching challenges • Whereas classical physics rewards students who can picture what is happening, quantum theory defies visualisation. • Abstract and counter-intuitive ideas need to be linked to visible phenomena and devices, including some already familiar to students. • Most A-level specifications trivialise the teaching of quantum phenomena and fail to distinguish it properly from classical physics. Scientific explanation • correlates separate observations • suggests new relations and directions • gives testable hypotheses (empirical ‘acid test’) Unifications in physics (a bit more history) Mechanical theory Electromagnetic theory (Newton, 1687) Entities: particles, inertia, force that lies along a line between interacting particles. (Maxwell, 1864) Entities: electric & magnetic fields, force that is perpendicular to both field & motion. celestial motions terrestrial motions, in 3-D heat (kinetic theory) magnetism electricity optics Relativity theory (Einstein, 1905 & 1916) unites all phenomena above Quantum theory (Planck 1900; Einstein 1905,16&17; Bohr & Heisenberg 1925; Schrodinger 1926; Dirac 1927; Bethe, Tomonaga, Schwinger, Feynman & Dyson 1940s …) atoms and nuclei Dissolves the classical distinction between point particles & nonlocal fields/waves. Quantum objects manage both at once. What went wrong? Classical physics could not explain • line spectra • electron configuration in atoms • black body radiation • photoelectric effect • specific thermal capacity of a crystalline solid • Compton scattering of X-rays The end of the mechanical age 1. Things move in a continuous manner. All motion, both in the large and small, exhibits continuity. 2. Things move for reasons. All motion has a history, is determinable and predictable. 3. The universe and all its constituents can be understood as complex machinery, each component moving simply. 4. A careful observer can observe physical phenomena without disturbing them. • Inside atoms, all of these statements proved false – we need another way of looking at the world on this scale ‘Quantum theory’ • Quantum mechanics • (electrons in atoms i.e. Chemistry, superconductors, lasers, semiconductor electronics) • Quantum field theory • quantum electrodynamics (interactions of light & matter, interactions of charged particles, annihilation & pair production) • electroweak unification (weak force + electromagnetism) • quantum chromodynamics (quarks & gluons) • Explains everything except gravity. Quantum theory in essence • only the probability of events is predictable • whatever happens in between emission and absorption, light is always emitted and absorbed in discrete amounts of energy. Einstein: ‘God does not play dice.’ Bohr: ‘Anyone who is not shocked by quantum theory has not fully understood it.’ Feynman: ‘things on a small scale behave nothing like things on a large scale.’ ‘I hope you can accept Nature as She is – absurd.’ Quantum theory in essence How photons travel • Photons seem to obey the command ‘explore all paths’. All the possibilities can be added up in a special way and used to predict what happens. Particle physics • The same approach is used to work out how quantum particles • change into one another - neutron (udd) decays to proton (uud) • interact with one another - electrons repel by exchanging a photon Scientists agree to differ • Agreed formalism, different interpretations Does the quantum world really exist, or is there only abstract quantum physical description? • Responses include: • Copenhagen interpretation (There is no objective reality. A quantum system has no properties until they are measured.) • ‘many worlds’ (All things happen, in a branching universe.) • non-local, hidden variables (an attempt to restore realism) Line spectra There is a ‘ladder’ of energy levels in the atom. Changes in electron arrangement correspond to the emission or absorption of a photon. E E hf 2 1 hc where h is the Planck constant, Line spectra This is what explains the line spectra that we have covered before. The colour palette could be imagined as a visual ‘map’ of the electron configuration for a specific element. Molecular spectra Atoms and molecules absorb & emit photons of characteristic energy or frequency, by changing their vibrational modes. Spectroscopy • to monitor car exhausts • to find the rotation rate of stars • to analyse pigments in a painting • to identify forensic substances • to map a patient’s internal organs Photoelectric effect Observations • There is a threshold frequency, below which no emission occurs. • The maximum Ek of the electrons is independent of light intensity. • Photoelectric current is proportional to light intensity. Photoelectric effect Photoelectric effect Photoelectric effect Photoelectric effect Analysis • Energy of photon E = hf high energy violet quantum Electron leaves metal Electron energy Quantum energy Potential well Work function (Diagram: resourcefulphysics.org) • The photon’s energy can do two things: • enable an electron to escape the metal surface • (work function, f). • give the free electron Ek. hf f E k max Photon flux • Calculate the number of quanta of radiation being emitted by a light source. • Consider a green 100 W light. For green light the wavelength is about 6 × 10-7 m and so: • Energy of a photon = E = hf = hc / λ= 3.3 × 10-19 J • The number of quanta emitted per second by the light, -1 100Js N 3 10 s 3.3 10 J 20 19 1 Wave-particle duality • Reflection, refraction, interference and diffraction can all be explained by the idea of light as wave motion. Polarisation also tells us that the waves are transverse. • The photoelectric effect means that we have to attribute some particle properties to light. • So, which is it? Wave-particle duality • We have to use different models to explain what happens in different situations. Neither is perfect. • Louis de Broglie suggested that this same kind of dual nature must also be applicable to matter. He proposed that any particle of momentum (p) has an associated wavelength λ = h/p = h/mv Where λ is know as the de Broglie wavelength de Broglie wavelength of an electron de Broglie wavelength of an electron • When you accelerate at about 100V then the wavelength is of the order of 10-10m. This is of the same magnitude as an X-ray. We know that X-rays can diffract because of their wave properties and so if this were all true and electrons could exhibit wave behaviour then they would demonstrate diffraction properties also. • In 1926 Davison and Germer tried it with a single nickel crystal. It worked! Electron diffraction The double-slit experiment with electrons number of electrons a) 10 b)200 c)6000 d)40 000 e) 140 000 polycrystalline target (a 2-dimensional grating) Question Time • TAP 501-3: Quanta – (wavelengths, energy and using E =hf) • Tap 502-2 Photoelectric effect question – (getting the electron out hf, and giving it some KE, ½ mv2) • TAP de Broglie worked examples • TAP 522-6 Electrons measure the size of a nuclei – (advanced)