* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Measles Vaccination - Global Virus Network

Poliomyelitis eradication wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Tuberculosis wikipedia , lookup

Traveler's diarrhea wikipedia , lookup

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Brucellosis wikipedia , lookup

Chagas disease wikipedia , lookup

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

Bioterrorism wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Typhoid fever wikipedia , lookup

Cysticercosis wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Anthrax vaccine adsorbed wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Leishmaniasis wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Meningococcal disease wikipedia , lookup

Neisseria meningitidis wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

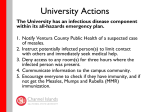

Measles: What’s old is new again by Jessica Eisner, MD* October 1, 2013 Before a vaccine was licensed in 1963, measles was a common disease that killed thousands of children each year in the United States. The first signs of measles are a cough, runny nose, and slight fever. It can take anywhere from 5 to 7 days before a patient develops a high fever and the “measles rash.” And, because the disease can be spread through a sneeze or a cough (or even if an infected person talks to you), many more people can be unknowingly infected before a diagnosis is made. While 70% of measles infections resolve uneventfully within 10 to 14 days, almost 30% of patients will experience a complication of the disease. The most common complications are diarrhea and ear infections. Other serious complications of measles include seizures, pneumonia and encephalitis. "Measles is a dangerous disease. We lose sight of the dangers because currently the disease is rare in the US and usually imported from other countries where measles is more prevalent,” explains Dr. Diane Griffin, GVN Center of Excellence Director and Alfred and Jill Sommer Professor and Chair, W. Harry Feinstone Department of Molecular Biology and Immunology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. An infectious disease – such as measles – that is widespread in a certain country is called “endemic” in that region. Measles was endemic in the United States from before its official founding in 1776 until the late 20th century. By 2000, measles had been eliminated in the United States. However, more people in the United States are not getting the proper vaccinations for their children and that is causing doctors and scientists to worry that the disease will become endemic again. “The most vulnerable in the US are those under the age of 12 to 15 months, when the measles vaccine is usually given. Infants are therefore at the highest risk. Those who do not vaccinate their own children place infants of other families at risk as well as their own children,” said Professor Griffin. Measles has also been a significant problem in high school and college students. “If only one dose of the vaccine is received, 5% will not be protected. This is why we use two doses. On a population scale, 5% of unprotected individuals adds up to many thousands. This is why we see outbreaks periodically on college campuses and in other situations where young people congregate in close quarters,” Professor Griffin explained further. In 2011, there were approximately 200 cases of measles in the United States. According to CDC reports, the number of cases in 2011 was more than triple the number of cases in 2009 and 2010. About half of the 2011 cases occurred during isolated outbreaks in unvaccinated people that were initiated by imported cases. With cases of measles increasing in the Unites States, the concern is that outbreaks in these pockets of unvaccinated people will result in constant transmission of the disease and measles will become endemic again. This has already happened in several countries in Europe. For example, measles had been under control in England. Now measles is endemic again there because of the increased numbers of unvaccinated people. There have been numerous recent sociological studies that identify different reasons why certain groups choose not to vaccinate their children - and the majority of these studies suggest that the impact and numbers of these groups is growing. The reasons for not vaccinating children range from medical to religious or philosophical, to fear of complications. In the United States vaccination is mandatory for school entry, but individual states vary in terms of how easily people can avoid vaccination. In some states, parents must provide evidence that vaccines should not be given. In other states, a parent need simply write a note requesting that the child not be vaccinated. The vast majority of measles infections in citizens of the United States occur in people who have not been vaccinated. “Measles is highly contagious and there is no curative therapy for it,” said Townson Tsai, an infectious disease physician at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center. “The problem often arises in home schooled children who may not be receiving the necessary vaccines. We now have an old disease -- readily preventable by vaccination -- becoming a new problem in the United States.” As experts and leading researchers on all viral diseases, GVN Centers of Excellence are working to improve the measles vaccine and better understand the complications of measles. “There is still much to do in terms of improving vaccinations against measles. While the two dose regimen provides protection for populations when delivered appropriately, a single dose regimen would be ideal and for developing countries a vaccine that did not need refrigeration or require a needle and syringe would facilitate delivery,” notes Professor Griffin, whose own laboratory focuses on understanding how the body responds to the measles vaccine to provide protection. She explained further that research to develop a dry powder vaccine delivered by inhalation is one promising line of research. “The dry powder vaccine uses the same safe live vaccine virus that is currently given by a shot, but is given through a face mask. This way trained medical personnel, refrigeration and needles and syringes are not required. The dry powder vaccine is effective in animal models and is currently being tested in humans. For the looming situation in the United States, Professor Griffin encouraged all families to ensure that their children are properly vaccinated against measles. “We cannot sit back and wait for measles to once again take hold in the United States,” she warned. * Dr. Eisner is an ad hoc volunteer to the Global Virus Network