* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Get results with the new marketing mix

Service parts pricing wikipedia , lookup

Food marketing wikipedia , lookup

Neuromarketing wikipedia , lookup

Bayesian inference in marketing wikipedia , lookup

Social media marketing wikipedia , lookup

Affiliate marketing wikipedia , lookup

Sales process engineering wikipedia , lookup

Target audience wikipedia , lookup

Ambush marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing research wikipedia , lookup

Marketing channel wikipedia , lookup

Marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Product planning wikipedia , lookup

Internal communications wikipedia , lookup

Youth marketing wikipedia , lookup

Multi-level marketing wikipedia , lookup

Viral marketing wikipedia , lookup

Customer experience wikipedia , lookup

Guerrilla marketing wikipedia , lookup

Digital marketing wikipedia , lookup

Customer relationship management wikipedia , lookup

Target market wikipedia , lookup

Customer satisfaction wikipedia , lookup

Marketing mix modeling wikipedia , lookup

Advertising campaign wikipedia , lookup

Multicultural marketing wikipedia , lookup

Integrated marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Marketing plan wikipedia , lookup

Green marketing wikipedia , lookup

Customer engagement wikipedia , lookup

Direct marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing strategy wikipedia , lookup

Street marketing wikipedia , lookup

Sensory branding wikipedia , lookup

Global marketing wikipedia , lookup

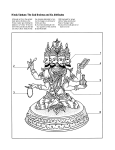

Simply Get results with the new marketing mix By Chekitan S. Dev and Don E. Schultz 36 ❘ MM March/April 2005 The traditional view and techniques have focused motion. We believe it’s time for of marketing assumes that an almost exclusively on new marketers to learn to implement organization should start with its customer acquisition and on a new marketing mix. Time to customers, learn their needs, generating profitable transac- take a different view of the value and then try to fill those needs— tions through cross-selling and creation process in organizations profitably and on an ongoing upselling, rather than on building by first building a customer-cen- basis. But that’s not the way it long-term relationships with tric view and then integrating really works today. customers over time. internal activities and processes. Marketing, as it has evolved In today’s interactive, net- In the January/February issue over the past half-centur y, has worked, and customer-controlled of Marketing Management, we not been developed to satisfy marketplace, we attribute much proposed a new marketing mix, customer wants and needs. of marketing’s inability to live up one that reflected the customer ’s Instead, in too many cases, it to the stated goals of “identifying point of view rather than view- has been used to assist firms in and satisfying customer needs point of the supplier or producer. disposing of products and serv- and wants” to the most common Instead of defining marketing in ices they have manufactured, of all marketing management terms of what it does, we created, developed, or simply concepts, the managerial rubric defined it in terms of what cus- wanted to vend at a profit. As a of the four Ps—the focus on tomers expect. We built a new result, most marketing concepts product, price, place, and pr o- mix based on our demand-based MM March/April 2005 ❘ 37 EXECUTIVE In our January/February Marketing Management article entitled “In the Mix,” we argued that briefing the four Ps are no longer a relevant marketing mix because they do not reflect 21st Century market realities. We defined a new marketing mix to change your marketing thinking: SIVA, which stands for solution, information, value, and access. This article describes the steps necessary to implement this new marketing mix and profiles a pioneering firm that adopted SIVA and realized immediate results. approach and called it SIVA—an acronym for these new customer-centric competencies and the order of their use: solutions, information, value, and access. The four imperatives we proposed are: develop and manage solutions not just products, offer information instead of simply promoting, create value instead of obsessing with price, and provide access wherever, whenever, and however the customer wants to experience your solution rather than thinking merely where to place your products. This approach suggests new opportunities, leads to different conclusions, and fundamentally changes the way you relate to customers. Some marketers recognize the change and get it. Others don’t. A recent full-page ad in The Wall Street Journal for SAP AG bore the headline: “Your Customers Expect Your Entire Enterprise To Revolve Around Them.” That’s impossible in a four Ps-driven supply-chain-led environment, but it’s critically important if a firm is to meet customer demand. Further, the four Ps are grounded in a manufacturing mind-set and need to be adapted to reflect the service economy. Thus the question for most marketing organizations is not “should we change?” but rather “what should we change, when, and how?” Value Creation Cycle If one were to visualize the way in which organizational managers generally use the four Ps, it might look something like Exhibit 1. Using the four Ps, the marketing manager would start with the evaluation of an organization’s assets base. Clearly, if an organization lacks assets, it most likely will be unable to develop any type of marketing activity. We therefore assume the firm has assets it can leverage in some way. The assets available to the marketing manager typically include facilities, financial resources, raw materials, intellectual capital, and the like. Such resources allow a company or organization to create something of value that it believes can be exchanged in the marketplace at a profit. Using the four Ps, the marketing manager takes an “inside-out” or “here’s-what-wecan-do” approach to marketplace entry and development. Four steps or stages commonly are used, starting with the identification of the corporate goals or what the management of the firm wants to achieve. Goals are usually set in terms of marketplace results or returns the firm wants to receive based on the use of its assets. Commonly, the second step is to identify the organizational resources that can or should be used to 38 ❘ MM March/April 2005 achieve the firm’s goals. The third step is where the four Ps start to emerge in earnest: Here, the organization develops and distributes its products and services, making choices that involve the product, the place or distribution, the promotion, and the price. The final step in this internally oriented, marketer-driven system is, of course, how the organization measures the success or results of its program and the returns it generates for its owners and shareholders. This approach fits the four Ps approach to a “T.” It is based on an internally driven system in which the marketer controls all the assets, all the resources, and all the power. In short, the marketer controls the system, sets the objectives, and determines the products and services and how and in what way to distribute them. Most importantly, the marketer measures the returns. So far, there’s not a customer in sight. In fact, if the marketing organization manages its four Ps-related resources right, customers never enter into the equation. They are superfluous and just get in the way. Consider the alternative externally focused approach, depicted graphically in Exhibit 2. This, we argue, is the way marketing in a 21st century organization should be developed and implemented. The marketing manager in our approach starts with the same asset base or the same resources shown in Exhibit 1. The difference, however, is that he or she would take a market- ■ Exhibit 1 Asset based–organizational view Set corporate goals Measure corporate returns Asset Base Identify corporate resources Develop/distribute products/services Adapted from Cranfield University driven rather than a firm-driven approach. The first step in a true market-driven approach is to understand the market and the customers based on true and deep customer insights. From that point, the goal would be to identify and clarify what customers value and determine whether the firm could create those values using the organization’s assets and resources. The second step involves identifying or creating various customer value propositions. That is, the marketing organization attempts to determine what customers want, need, and value, and then focuses its resources and asset base on fulfilling those wants and needs. The third step is just as simple. Rather than focusing on products and services that could be made, assembled, or developed, the organization finds ways to deliver the value customers seek. The fourth step is, then, almost a naturally occurring event in which the organization measures the extent to which the customer value was delivered, not just the returns to the corporation or marketing firm. Looking at this rather simplistic example, four Ps proponents will argue that focusing on the customer and meeting customer needs and wants is inherent in the traditional four Ps process. They will say that research with customers must be done before products can be made or that distribution channels must be selected that fit a customer’s requirements. And, while this rhetoric is good, in practice the four Ps approach generally never gets started or implemented in a customer-focused way. The comparison of the two approaches here clearly illustrates, however, that the four Ps approach is internally driven, organizationally focused, and ignores customers. That, quite simply, is our point. The four Ps does not reflect the marketing concept—it is simply a managerial tool that is driven by a manufacturer-driven concept that cannot be supported in the much more customer-oriented marketplace that exists today. Stemming customer turnover has become the new marketing mantra and yet with the four Ps approach, that can never happen. Taking a new approach to building the business for and around the customer must become one of the firm’s core competencies. Marketing must become a process in which all the customer-touching elements are connected and aligned. tion-generating activities of the organization. And that’s part of the organizational problem of the four Ps. Internal marketing, internal alignments, and internal systems are the tasks of the new organization. Today, much of our internal marketing activity either doesn’t occur or falls between the cracks in the firm—between marketing and HR for example, or between marketing and IT or between marketing and operations. One of the greatest challenges to marketing is to align and integrate the entire organization through processes and systems, particularly the employees, channels, business associates, and other stakeholders who actually deliver the solutions the customers believe they are purchasing. Finding the better, faster, cheaper, smarter way to get the solution in the customer’s hands becomes the key imperative. Once this thinking is in place, the employees of the firm then need to be trained as problem solvers and value deliverers with support from the marketers, who in turn need to become knowledge providers and access creators. Just Do It Clearly, the question arises: Is SIVA just another clever marketing mnemonic device that reiterates what marketers are already doing or have done in the past? We believe SIVA supports and builds on the true marketing concept—finding customer needs, wants, or desires and fulfilling them at a profit to the marketing organization. The reason? SIVA suggests a radically different approach to think, plan, and develop marketing programs. A case example of SIVA in action illustrates the point. Southern LINC is a division of Southern Co., the parent company of several electric utilities operating in the Southeast. Southern LINC grew out of a set of tools and technologies originally developed by Motorola and chosen for use by Southern Co. to replace aging dispatch systems being used by utility companies. ■ Exhibit 2 Asset based–customer view Understand markets and customer value Internal Activities and Processes We have known all along that marketing efforts manage only a portion of the customer experience. In most organizations, the sales force, customer service personnel, and frontline, customer-facing people do not report to marketing; in fact, most do not consider themselves to be involved in the marketing process. Yet, the quality of the experience customers have with a product or service, not just the quality of the product itself or the delivery of the service, has much to do with whether or not they return and repurchase. So, yes, marketing is responsible for retention but not for the reten- Measure the value delivered Asset Base Create customer value proposition Deliver customer value Adapted from Cranfield University MM March/April 2005 ❘ 39 Recognizing the need for a highly reliable communication network for the utility operations, the Motorola iDEN (Integrated Digital Enhanced Network) technology was chosen as the solution for a mobile communication system for its own internal use. The iDEN technology combines two-way radio, cellular, paging, and Internet access through one integrated handset. Southern Co. recognized that the iDEN technology could provide more capacity than its operating companies required. This would allow them to sell the additional capacity to provide a communication solution that would meet the needs of other business and government users, providing additional revenue to Southern Co. The system was built to cover 127,000 square miles across four states and was designed to withstand adverse weather conditions and to cover both the metropolitan and rural areas that the electric utilities served. Southern LINC began offering services as early as 1994, and officially launched commercial services across the footprint in 1996. Like many other technology-driven organizations, initially the Southern LINC focus was on the products and services, not on the customer benefits that the service provided. As with most other telecommunications organizations, Southern LINC was organized and operated on functional lines. That enabled the firm to develop the various areas such as technology, finance, operations, marketing, sales, and so on quickly and efficiently. Although the functional managers worked well together horizontally (i.e., technology managers met with and worked directly with customer service and the financial team worked directly with the various product managers), Bob Dawson, CEO, felt the organization was missing something. The group held an annual meeting where all functional groups came together to plan the coming year, but the focus was still on trying to sell what Southern LINC had to offer. Starting in 1998, Julie Pigott, vice president of marketing, began to organize the annual planning meeting around teambuilding and cross-functional team interactions. That brought the group together and created a common ground for product and service development and delivery. But Dawson and Pigott still felt the organization was missing a customer orientation. Clearly, based on the annual gathering, the Southern LINC functional groups wanted to become more customer oriented. And senior management was encouraging them to do so. The problem was they lacked a framework to help them start with customers, rather than with products and services. Southern LINC had discovered what so many other marketing organizations were learning, that the four Ps was an internally oriented approach to marketing. It focused on what the company wanted to do, not what customers needed or wanted. No matter how much better Southern LINC got at managing the various marketing activities, their processes always started with products and services, not with customers. “At our annual planning meeting, we met as a group. We worked together. We identified the common problems that needed to be solved. We got the functional groups to agree on what needed to be done. We generated a number of solutions but, when it came time for implementation, something was missing,” said Pigott in reviewing the 2003 meeting. Pigott discussed the problem with Heidi Schultz, executive vice president of Agora Inc., the external marketing consultant to Southern LINC. Agora Inc. had been developing the concept of SIVA, and Pigott and Schultz agreed to use the SIVA framework as the basis for the annual Southern LINC planning meeting in August 2003. The annual meeting was planned around the use of the SIVA concept. In the opening sessions, Southern LINC functional managers were immersed in the approach as the model for their future planning. The impact was almost immediate. Dawson, Southern LINC’s CEO, said he saw it in the discussions in the planning sessions in the 2003 meeting. Rather than talking about product improvements and enhancements, the managers of the various functional groups began to talk about customer needs: What are those needs? How are they currently being met? By whom, if not Southern LINC? What does the organization need to do to solve customer problems and provide solutions? “We began to look for ways to provide what customers wanted and needed, not to just find new or different or better ways to tell prospects about the nifty new features that Southern LINC was developing” said Rodney Johnson, vice president of sales and distribution. Customer problems and solutions became the issues for the discussion during the intensive three-day planning program. One of the key elements to emerge from the 2003 planning meeting was the group consensus that, despite the improvements in the product offerings—such as enhancements in customer service, extensions, and expansions of the network—the theme that kept running through all the manager’s discussions was: “We have to make it easier for customers to do business with us.” Overall, the feeling was: “We’re still too SIVA supports and builds on the true marketing concept—finding customer needs, wants, or desires and fulfilling them at a profit to the marketing organization. 40 ❘ MM March/April 2005 hard to do business with. We’ve developed truly novel and efficient systems that serve our internal needs, but we may have made it too complicated for customers. We’re not sufficiently customer-focused or customer-oriented. We’re better than two years ago, but to compete as a regional player against multinational competitors with deep pockets, we have to be a company that anticipates customers’ needs and steps up to meet them across the whole range of service delivery points.” These themes framed the objectives for 2004. Using SIVA, six groups were formed to tackle key strategic initiatives designed to: • Understand the service needs of specific geographic and industry segments and develop products/services accordingly. (S and I) • Improve network coverage where needed. (S and V) • Provide outstanding value by managing processes to deliver excellent service at a reasonable cost. (S and V) • Develop a long-term, integrated multi-channel distribution strategy. (I and A) • Improve business process from a customer perspective. (S, I, and V) • Launch new products and services. (S, I, V, and A) The six groups set about following the SIVA process. Starting with customers, they identified the solutions customers wanted. They then looked at how well Southern LINC provided those solutions. Next, they determined the information customers wanted Southern LINC to supply and the form and manner in which those customers wanted it available and delivered, not merely how Southern LINC wanted to distribute it. Then, they looked at value, not in the sense of cost benefit, but in terms of customer experiences. What was Southern LINC doing that created customer problems or customer concerns or questions? How could they reduce those problems or issues, whether they came in the form and format in which billing was done to the number of rings customer service set as a goal for answering incoming customer telephone service requests. The total customer experience became the beacon for the Southern LINC managers, more than the network or system or reliability of the service. By looking at customers first, Southern LINC managers began to imagine new ways to expand and extend their services. And, of course, access became a key issue. It was not just a case of how Southern LINC wanted to reach their customers and prospects, it was how the customer wanted to access the information and material they needed from the organization. It was also about how the customer wanted to be served or the type of relationship the customer wanted, not how Southern LINC wanted to deliver the service or relationship. The SIVA approach turned the organization upside down, but not in a destructive, change-management sense. SIVA provided the process Southern LINC managers needed to understand their customers, to really know what they wanted, needed, required, and would be willing to pay for. Best of all, SIVA provided the framework for a horizontal planning system in which marketing became something the entire organization did, not something a group of functional marketing managers did. Is the SIVA system completed at Southern LINC? Not by a long shot. During 2003, the Southern LINC managers identified dozens of issues to address. Some were capital intensive. Some were cultural. Some were simply things that had developed as policies and procedures as the company had developed and grown that had never been questioned. And, some were hold-overs from the regulatory environment that are the roots of the communication and utility organization. All had to be rethought and reappraised, not in terms of “how can we fix them?” Instead, they should be thought of in terms of “what solutions, information, value, and access do customers want and how can we provide them?” “It’s a whole new way of thinking for all of us,” commented Pigott at the end of the 2003 planning session. The Bottom Line The SIVA approach continues to serve its purpose at Southern LINC. It has helped a technologically driven company move from a product and service focus to a customer orientation. It has brought the organization together horizontally. Although the organization is still functionally organized, as it likely should be, it has helped provide a horizontal process that allows various functional managers and functional specialists to work across the organization to solve customer problems efficiently and effectively. From a management view, it has helped the middle managers identify the changes that need to be made. It has allowed them to take on board, identify, value, and prioritize the recommendations they now present to senior management for funding. Most of all, however, SIVA has provided the catalyst for a very strong and capable organization to move to the next level of marketing thinking by building a better model. It allowed the organization to escape the restraints of the internally focused methodology of the four Ps and move to the customer-oriented SIVA approach better suited to the realities of the 21st century marketplace. ■ About the Authors Chekitan S. Dev is a marketing professor at Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration in Ithaca, N.Y. He may be reached at [email protected]. Don E. Schultz is a professor emeritus of integrated marketing communications (IMC) at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, and the president of Agora Inc. in Evanston, Ill. He may be reached at [email protected]. MM March/April 2005 ❘ 41