* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download VALVULER HEART DISEASE

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Infective endocarditis wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Pericardial heart valves wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatic fever wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Aortic stenosis wikipedia , lookup

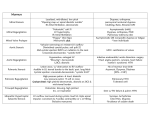

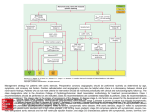

VALVULER HEART DISEASE Yrd.Doç.Dr.Olcay ÖZVEREN Aortic Stenosis Pathology : Obstruction to left ventricular (LV) outflow Causes : a congenital bicuspid valve with superimposed calcification calcification of a normal trileaflet valve (senile or degenerative ) rheumatic disease The risk factors of calcific AS Similar to those for vascular atherosclerosis : .elevated serum levels of LDL cholesterol and lipoprotein(a) .Diabetes .Smoking .hypertension. Rheumatic Aortic Stenosis Rheumatic AS results from adhesions and fusions of the commissures and cusps and vascularization of the leaflets of the valve ring, leading to retraction and stiffening of the free borders of the cusps. Calcific nodules develop on both surfaces, and the orifice is reduced to a small round or triangular opening The rheumatic valve is often regurgitant, as well as stenotic. Patients with rheumatic AS invariability have rheumatic involvement of the mitral valve . Pathophysiology Classification of the Severity of AS Symptoms exertional dyspnea (LV diastolic dysfunction, with an excessive rise in end-diastolic pressure leading to pulmonary congestion and the limited ability to increase cardiac output with exercise ) Angina (precipitated by exertion and relieved by rest. Angina results from the combination of the increased oxygen needs of hypertrophied myocardium and reduction of oxygen delivery secondary to the excessive compression of coronary vessels ) Syncope (reduced cerebral perfusion that occurs during exertion when arterial pressure declines consequent to systemic vasodilation in the presence of a fixed cardiac output heart failure ) Physical Examination parvus and tardus carotid impulse (slow-rising, latepeaking, low-amplitude carotid pulse . However, in patients with associated AR or in older patients with an inelastic arterial bed, systolic and pulse pressures may be normal or even increased. ) The cardiac impulse is sustained and becomes displaced inferiorly and laterally . systolic thrill (It is palpated most readily in the second right intercostal space or suprasternal notch and is frequently transmitted along the carotid arteries. ) Auscultation The ejection systolic murmur Typically is late peaking and heard best at the base of the heart, with radiation to the carotids . Cessation of the murmur before A2 is helpful in differentiation from a pansystolic mitral MR murmur. In patients with calcified aortic valves, the systolic murmur is loudest at the base of the heart, but high-frequency components may radiate to the apex (Gallavardin phenomenon), in which the murmur may be so prominent that it is mistaken for the murmur of MR. A louder and later peaking murmur indicates more severe stenosis. When the left ventricle fails and stroke volume falls, the systolic murmur of AS becomes softer; rarely, it disappears altogether. The slow rise in the arterial pulse is more difficult to recognize The intensity of the systolic murmur varies from beat to beat when the duration of diastolic filling varies, as in AF or following a premature contraction. This characteristic is helpful in differentiating AS from MR, in which the murmur is usually unaffected. Splitting of the second heart sound helpful in excluding the diagnosis of severe AS because normal splitting implies the aortic valve leaflets are flexible enough to create an audible closing sound (A2). Diagnostic Evaluation Modalities Echocardiography (definition of valve anatomy, including the cause of AS and the severity of valve calcification, evaluation of LV hypertrophy and systolic function, mean transaortic pressure gradient with calculation of the ejection fraction, and for measurement of aortic root dimensions and detection of associated mitral valve disease.) Cardiac Catheterization and Angiography Computed Tomography Cardiac MR Clinical Outcome Asymptomatic Symptomatic 2 years in patients with heart failure 3 years in those with syncope 5 years in those with angina The average rate of hemodynamic progression : annual decrease in aortic valve area of 0.12 cm2/year an increase in aortic jet velocity of 0.32 m/sec/year an increase in mean gradient of 7 mm Hg/year. Exercise test is helpful : Symptoms on treadmill exercise a decrease in blood pressure with exertion An elevated BNP level may be helpful when symptoms are equivocal or when stenosis severity is only moderate. Management Symptomatic patients with severe AS are usually operative candidates because medical therapy has little to offer . Medical therapy may be necessary for patients considered to be inoperable , HF , HT, CAD. Diüretics ,ACE inh. ,Statins, DC Cardiversion in AF Surgical Treatment Aortic Regurgitation Causes and Pathology Valvular Disease Aortic Root Disease calcific AR infective endocarditis trauma congenitally bicuspid valve Rheumatic fever SLE rheumatoid arthritis ankylosing spondylitis Takayasu disease, Marfan syndrome; aortic dilation related to bicuspid valves aortic dissection, osteogenesis imperfecta, syphilitic aortitis, ankylosing spondylitis, the Beh?et syndrome, giant cell arteritis, Whipple disease, systemic hypertension Pathophysiology Clinical Presentation exertional dyspnea Angina Syncope heart failure Physical Findings Quincke's Pulse: Capillary pulsation visible on the fingernail beds or tips Musset's Sign: Head bobbing with each heartbeat Müller’s Sign: Systolic pulsation of the uvula Corrigan’s Pulse: Water-hammer pulse. Rapid distention and collapse of arteriel pulse Hill’s Sign: Popliteal cuff pressure more than 60 mmHg above brachial cuff pressure Duroziez’s Sign: To-and-fro murmur over the femoral artery with the artery compressed Traube’s sign: Pistol-shot sounds. Prominent systolic and diastolic sounds over the femoral arteries Increased pulse pressure (SBP increases and DBP decreases.) Diastolic Murmur In AR •In moderate AR, a relatively loud early desending diastolic murmur is heard. •With more severe AR, the murmur becomes longer, and will usually decrease in intensity. •The classic murmur caused by the regurgitant flow is best heard along the lower left sternal border. In some cases (Marfan’s Syndrome, VSD w/AR , aortic dissection or aneurysm) it is best heard at the right sternal border. • A lower-pitched mid-diastolic murmur is heard over apex this indicates what is called an Austin Flint murmur which indicates severe AR. (The murmur is not the regurgitant flow over the aortic valve, but rather vibrations in a restricted Mitral Valve when the left atrium empties and is met with the opposite flow from the aortic valve.) •In addition to the diastolic murmur(s), a systolic flow murmur like in aortic stenosis may be heard. This is not necessarily indicating a calcified valve, as the increased velocity resulting from ventricular overload will also cause flow vibrations) Diagnostic Evaluation Modalities Echocardiography (bicuspid valve, thickening of the valve cusps, other congenital abnormalities, prolapse of the valve, a flail leaflet, or vegetation ) Electrocardiography (left axis deviation and a pattern of LV diastolic volume overload, characterized by an increase in initial forces (prominent Q waves in leads I, aVL, and V3 through V6) and a relatively small wave in lead V1 ) Radiography Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Angiography electrocardiography Chest x ray echocardiography Disease Course asymptomatic symptomatic Management Medical Treatment :There is no specific therapy to prevent disease progression in chronic AR. Systemic arterial hypertension, should be treated because it increases the regurgitant flow; vasodilating agents such as ACE inhibitors or ARB are preferred, and beta-blocking agents should be used with great caution. Chronic medical therapy may be necessary for some patients who refuse surgery or are considered to be inoperable because of comorbid conditions. These patients should receive an aggressive heart failure regimen with ACE inhibitors (and perhaps other vasodilators), digoxin, diuretics, and salt restriction; beta blockers may also be beneficial. Surgical Treatment Acute Aortic Regurgitation Causes: infective endocarditis, aortic dissection, trauma The characteristic features of acute AR are tachycardia and an increase in LV diastolic pressures. The sudden increase in LV filling causes the LV diastolic pressure to rise rapidly above left atrial pressure during early diastole . Premature closure of the mitral valve, together with tachycardia that also shortens diastole, reduces the time interval during which the mitral valve is open. The tachycardia may compensate for the reduced forward stroke volume, and the LV and aortic systolic pressures may exhibit little change. Acute severe AR may cause profound hypotension and cardiogenic shock . Weakness, severe dyspnea, and profound hypotension secondary to the reduced stroke volume and elevated left atrial pressure . Physical Examination tachycardia, severe peripheral vasoconstriction, and cyanosis, and sometimes pulmonary congestion and edema. S1 may be soft or absent because of premature closure of the mitral valve, and the sound of mitral valve closure in mid or late diastole is occasionally audible. Closure of the mitral valve may be incomplete, and diastolic MR may occur The early diastolic murmur of acute AR is lower pitched and shorter than that of chronic AR because as LV diastolic pressure rises, the (reverse) pressure gradient between the aorta and left ventricle is rapidly reduced. Echocardiography:In acute AR the echocardiogram reveals a dense, diastolic Doppler signal with an end-diastolic velocity approaching zero and premature closure and delayed opening of the mitral valve. LV size and ejection fraction are normal. Electrocardiography: In acute AR, the ECG may or may not show LV hypertrophy, depending on the severity and duration of the regurgitation. However, nonspecific ST-segment and T wave changes are common. Radiography :In acute AR, there is often evidence of marked pulmonary venous hypertension and pulmonary edema. Management Early death caused by LV failure is frequent in patients with acute severe AR despite intensive medical management, prompt surgical intervention is indicated. Even a normal ventricle cannot sustain the burden of acute, severe volume overload. While the patient is being prepared for surgery, treatment with an intravenous positive inotropic agent (dopamine or dobutamine) and/or a vasodilator (nitroprusside) is often necessary. In hemodynamically stable patients with acute AR secondary to active infective endocarditis, operation may be deferred to allow 5 to 7 days of intensive antibiotic therapy . However, AVR should be undertaken at the earliest sign of hemodynamic instability or if echocardiographic evidence of diastolic closure of the mitral valve develops. MITRAL STENOSIS MITRAL VALVE ANATOMY Etiology 1. Rheumatic Fever 2. Congenital Mitral Stenosis Pathophysiology 1. Increased left atrial pressure 2. Pulmonary vasoconstriction 3. Pulmonary Hypertension 4. Right Ventricular Failure 5. Decreased cardiac output Pathophysiology Right Heart Failure: Hepatic Congestion JVD Tricuspid Regurgitation RA Enlargement RV Pressure Overload RVH RV Failure Pulmonary HTN Pulmonary Congestion LA Enlargement Atrial Fib LA Thrombi LA Pressure LV Filling Symptoms Fatigue Palpitations Cough Chest pain SOB Left sided failure Orthopnea PND Exercise Palpitation Hoarseness (Ortner’s syndrome Afib Systemic embolism Pulmonary infection Hemoptysis Right sided failure Hepatic Congestion Edema Precipitating Factors Exertion Fever Anemia Pregnancy Atrial Fibrillation hypertiroid Recognizing Mitral Stenosis Palpation: Small volume pulse Tapping apex-palpable S1 +/- palpable opening snap (OS) RV lift Palpable S2 ECG: LAE, AFIB, RVH, RAD Auscultation: Loud S1- as loud as S2 in aortic area A2 to OS interval inversely proportional to severity Diastolic rumble: length proportional to severity In severe MS with low flow- S1, OS & rumble may be inaudible Mitral Stenosis: Physical Exam S1 S2 OS S1 First heart sound (S1) is accentuated and snapping Opening snap (OS) after aortic valve closure Low pitch diastolic rumble at the apex Pre-systolic accentuation (esp. if in sinus rhythm) © Continuing Medical Implementation …...bridging the care gap Common Murmurs and Timing Systolic Murmurs Aortic stenosis Mitral insufficiency Mitral valve prolapse Tricuspid insufficiency Diastolic Murmurs Aortic insufficiency Mitral stenosis S1 S2 os S1 Signs: Later findings of right ventricular failure •Accentuated precordial thrust of right ventricle •Elevated neck veins •Ascites •Edema Complications Hemoptysis Embolism Pulmonary infection Endocarditis Atrial fibrillation Radiology Chest XRay Double density of left atrial enlargement Right ventricular enlargement Posterior displacement of esophagus Mitral valve calcification Kerley B Lines Echocardiogram Mitral valve leaflet changes Inadequate separation of valve leaflets Valve leaflet calcification and thickening Doppler estimates transvalvular gradient Mitral Stenosis - upper lobe blood diversion Trivial enlargement of the transverse diameter of the heart. Left atrium causes double outline (opposite right arrow) and is somewhat dilated. Left atrial appendage is dilated, causing a prominence of the left border (opposit left arrow). Upper lobe vessels larger than lower lobe vessels, that is, upper lobe blood diversion. An arrow points to a dilated upper lobe vein. Mitral Stenosis - septal line shadows. Kerley "B" Horizontal short line shadows, septal (Kerley "B") lines above the costo-phrenic recesses, indicating interstitial oedema of the septa, often with haemosiderin in the adjacent alveoli. Mitral Stenosis - hilar oedema Hilar vessels indistinct, peri-hilar haze. Also upper lobe blood diversion and septal line shadows. Arrow points to a Kerley "A" line, due either to septal oedema or oedema around an intercommunicating lymphatic during its course from a perivenous to a pericardial position or vice versa. echocardiography Prognosis Slow, progressive, life-long course Latent period of 20 to 40 years after Rheumatic Fever Rapid acceleration of symptoms in later life Management Rheumatic Fever prophylaxis until age 35 years Benzathine Penicillin G 1.2 MU IM monthly OR Penicillin VK 125-250 mg PO bid Treat complications and associated conditions Atrial Fibrillation Congestive Heart Failure Anticoagulation for history of emboli Beta blocker. Digitalis.diüretics Surgery Open Mitral valvotomy Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty Mitral Valve Replacement MITRAL REGURGITATION MITRAL VALVE ANATOMY Etiology Rheumatic Heart Disease Mitral Valve Prolapse Ischemic Heart Disease and papillary muscle dysfunction Left Ventricular dilatation Mitral annular calcification Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Infective endocarditis Congenital mitral regurgitation Pathophysiology Early or compensated mitral regurgitation Volume overload Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Left atrial enlargement Late or decompensated mitral regurgitation Left Ventricular Failure Decreased ejection fraction Pulmonary congestion Pathophysiology of mitral regurgitation In the normal heart, left ventricular (LV) contraction during systole forces blood exclusively through the aortic valve into the aorta; the closed mitral valve prevents regurgitation into the left atrium (LA). In mitral regurgitation (MR), a portion of the LV output is forced retrograde into the LA, so that forward cardiac output into the aorta is reduced. In acute MR, the LA is of normal size and is noncompliant, such that the LA pressure rises markedly and pulmonary edema may result. In chronic MR, the LA has enlarged and is more compliant, such that LA pressure is less elevated and pulmonary congestive symptoms are less common if LV contractile function is intact. There is LV enlargement and eccentric hypertrophy due to the chronic increased volume load. Pathophysiology The severity of MR and the ratio of forward cardiac flow (cardiac output) to backward flow are determined by several, interacting factors: 1) the size of the mitral orifice during regurgitation 2) the systemic vascular resistance opposing forward flow from the ventricle 3) the compliance of the left atrium 4) the systolic pressure gradient between the LV and the LA 5) the duration of regurgitation during systole (not all regurgitation is holo-systolic) Symptoms Dyspnea Fatigue Weakness Cough Physical findings Holosystolic Murmur at Apex Harsh, medium pitched pansystolic murmur Murmur obliterates M1 Radiation Axilla Upper sternal borders Subscapular region Soft or diminished First Heart Sound (S1) P2 heart sound augmented S2 Heart Sound with wide split S3 Gallop rhythm (indicative of severe disease) Accentuated and displaced precordial Apical Thrust Systolic thrill MURMUR Laboratuary findings Electrocardiogram Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Left Axis Deviation Chest XRay Enlarged left atrium Dilated left ventricle Echocardiogram Enlarged left atrium Hyperdynamic left ventricle Doppler assess severity CHEST X-RAY echocardiography Monitoring Annual or semi-annual echocardiogram Assess ejection fraction Assess end-systolic dimension Management Anticoagulation in Atrial Fibrillation Treat Congestive Heart Failure Diuretics Digoxin Afterload reduction ACE Inhibitor Hydralazine Nitroprusside (especially acute MR) Surgery Mitral Valve repair or replacement Repair before Heart Failure develops Keep ejection fraction >60% Keep end-systolic dimension <45 mm Indications Cardiopulmonary Symptoms (NYHA Class II-IV) Left Ventricular function impaired Tricuspid Valve Diseases The forgotten valve Tricuspid Valve Anatomy TV annuluss • The tricuspid valve is the most apically (or caudally) placed valve with the largest orifice among the four valves. • The tricuspid annulus is oval-shaped and when dilated becomes more circular. • 20% larger than MV annulus . • Normal TV annulus= 3.0 - 3.5 cm Leaflets the tricuspid valve has three distinct leaflets described as septal, anterior, and posterior. The septal and the anterior leaflets are larger. The posterior leaflet is smaller and appears to be of lesser functional significance since it may be imbricated without impairment of valve function. Leaflets The septal leaflet is in immediate proximity of the membranous ventricular septum, and its extension provides a basis for spontaneous closure of the perimembranous ventricular septal defect. The anterior leaflet is attached to the anterolateral margin of the annulus and is often voluminous and sail-like in Ebstein’s anomaly. Papillary Muscles & Chordae There are three sets of small papillary muscles, each set being composed of up to three muscles. The chordae tendinae arising from each set are inserted into two adjacent leaflets. the anterior set chordae insert into half of the septal and half of the anterior leaflets. The medial and posterior sets are similarly related to adjacent valve leaflets. Etiology of Primary Tricuspid Valve Disease Congenital —Cleft valve generally in association with atrioventricular canal defect —Ebstein’s anomaly —Congenital tricuspid stenosis —Tricuspid atresia • Rheumatic valve disease, generally in association with rheumatic mitral valve disease • Infective endocarditis • Carcinoid heart disease • Toxic (eg, Phen-Fen valvulopathy or methysergide valvulopathy) • Tumors (eg, myxoma) • Iatrogenic—pacemaker lead trauma • Trauma—blunt or penetrating injuries • Degenerative—tricuspid valve prolapse • Etiology of Secondary or Functional Tricuspid Valve Disease • • • • Right ventricular dilatation Right ventricular hypertension Global right ventricular dysfunction resulting from cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, or longstanding right ventricular hypertension with fibrosis Segmental dysfunction secondary to ischemia or infarction of the right ventricle, endomyocardial fibrosis, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia Clinical Presentations Pure or predominant tricuspid stenosis Pure or predominant tricuspid regurgitation Mixed Tricuspid valve disease— Symptoms • • • • • • • Fatigue Liver/gut congestion Right upper quadrant discomfort Dyspepsia Indigestion Fluid retention with leg edema Ascites Tricuspid valve disease ausculatory findings Stenosis : Low-to medium-pitch diastolic rumble with inspiratory accentuation Regurgitation : Soft, early, or holosystolic murmur Augmented with inspiratory effort (Caravallo’s sign) Prolapse : Systolic click • Substantial tricuspid regurgitation may exist without the classic ausculatory findings. Thus, clinical evaluation including cardiac auscultation cannot be used to exclude tricuspid valve disease. Transthoracic Echo Views Transesophageal Views Transesophageal Views Key Diagnostic Features Mild TR is seen in up to 60% and Moderate TR in up to 15% of healthy individuals. Mild or worse TR in a valve with thin leaflets, normal coaptation, and normal-appearing supporting structures, suggests regurgitation is physiologic or functional . Key Diagnostic Features In carcinoid disease, the leaflets are thickened and retracted with a fixed orifice usually leading to predominant regurgitation and less severe stenosis. Approximately 30% of patients with MVP have redundancy and prolapse of the tricuspid valve, leading to TR. TR & TS Severity PAP based on TR Velocity Mild increased PAP = 2.6 - 2.9 m/s (27-33 mmhg) Moderate increased PAP = 3.0 - 3.9 m/s (36-60 mmhg) Severe increased PAP = 4.0≤ (64 mmhg ≤ ) European Guideline for TV managment AHA/ACC Guideline for TV managment