* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download amino acid mixture

Catalytic triad wikipedia , lookup

Metalloprotein wikipedia , lookup

Fatty acid metabolism wikipedia , lookup

Butyric acid wikipedia , lookup

Citric acid cycle wikipedia , lookup

Nucleic acid analogue wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

Fatty acid synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides wikipedia , lookup

Proteolysis wikipedia , lookup

Protein structure prediction wikipedia , lookup

Peptide synthesis wikipedia , lookup

Calciseptine wikipedia , lookup

Genetic code wikipedia , lookup

Biochemistry wikipedia , lookup

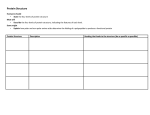

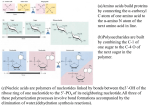

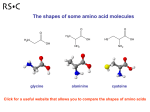

CIinical Science and Molecular Medicine (1917) 53, 21-33. Effect of glycylglycine on absorption from human jejunum of an amino acid mixture simulating casein and a partial enzymic bydrolysate of casein containing small peptides P. D. F A I R C L O U G H , D. B. A. S I L K , M. L. C L A R K , D. M. MATTHBWS,") T. C . MARRS,(I)D. BURSTON")AND K. M. CLEGG(2) Department of Gastroenterology, St Bartholomew's Hospital, London, (I'Department of Experimental Chemical Pathology, Vincent Square Laboratories. Westminster Hospital, London. and "'Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, Scotland, U.K. (Received 25 November 1976; accepted 18 February 1977) Summary 1. A jejunal perfusion technique has been used in normal volunteer subjects to study jejunal absorption of amino acid residues from a partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein in which about 50% of the amino acids existed as small peptides, and also from an equivalent mixture of free amino acids. 2. The effect of a high concentration of the dipeptide glycylglycine on the absorption of amino acid residues from these preparations was studied to quantify the importance of mucosal uptake of intact peptides during absorption of the partial hydrolysate of casein. 3. The results were unexpected. Glycylglycine significantly inhibited absorption of several amino acid residues (aspartic acid asparaghe, serine, glutamic acid + glutamine, proline, alanine, phenylalanine, threonine and isoleucine) from the free amino acid mixture, whereas it significantly inhibited the absorption of only two (serine, glutamic acid fglutamine) from the peptide-containing partial casein hydro1ysate. 4. The effect of glycylglycine on absorption of amino acids from the mixture of free amino acids was apparently due to inhibition of amino acid uptake by free glycine liberated from the dipeptide during perfusion. The reason for the failure of glycylglycine to cause extensive inhibition of absorption from the partial hydrolysate is not clear. It may be due to glycylglycine being only a weak inhibitor of + Correspondence: Dr D. B. A. Silk, Liver Unit, King's College Hospital, London, S.E.J. peptide uptake, but the possibility that some peptides are taken up by a system unavailable to glycylglycine has to be considered. Key words: absorption, amino acids, casein, glycylglycine, peptides. Introduction After a protein meal the lumen of the small intestine contains a complex mixture of free amino acids and small peptides (Adibi & Mercer, 1973) but the relative contribution of mucosal uptake of amino acids and that of peptides to overall absorption of proteindigestion products is unknown (Matthews, 1975). We have therefore attempted to estimate the quantitative importance of peptide absorption from a partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein, in which about 50% of the amino acids were in the form of small peptides of chain length two to four amino acids, and about 50% as free amino acids (Clegg & McMillan, 1974). We hoped to estimate the contribution of mucosal uptake of intact peptides to total amino acid absorption from this mixture by using another peptide in high concentration, so as to inhibit absorption of the peptide fraction of the partial enzymic hydrolysate. Glycylglycine was chosen as it is known to inhibit absorption of a number of other diand tri-peptides in vitro (Rubino, Field & Schwachman, 1971; Addison, Matthews & Burston, 1974; Addison, Burston, Dalrymple, Matthews, Payne, Sleisenger & Wilkinson, 27 28 P. D. Fairclough et al. 1975). Available evidence also suggests that it is mostly absorbed intact and hydrolysed within the cell cytoplasm (Matthews, Craft, Geddes, Wise & Hyde, 1968; Adibi, 1971; Hellier, Holdsworth, McColl & Perrett, 1972; Silk, 1974). It was therefore presumed that it would cause a minor inhibition of absorption of free amino acids. Using an intestinal perfusion technique in man, we have therefore examined the effect of high concentrations of glycylglycine on absorption of amino acids from the partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein, and also from a mixture of the same amino acids, all of which were in the free form. As our analysis of the partial enzymic hydrolysate showed it to contain a broad spectrum of peptides, the first investigation tested the effect of a single dipeptide on absorption of amino acids from a heterogeneous mixture of peptides and amino acids. Methods Enzymic hydrolysate of casein and amino acid mixture The partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein was prepared by hydrolysis with papain, followed by hydrolysis with pig kidney peptidases (CIegg & McMillan, 1974; Silk, Clark, Marrs, Addison, Burston, Matthews & Clegg, 1975). The equivalent amino acid mixture simulating the pattern and molar concentration of casein was made up in the same proportions as described by Silk et al. (1975) to a final concentration of 24.9 mmol of a-amino nitrogen/] (determined after acid hydrolysis) (Table 1). Analysis of casein hydrolysate Free amino acids were removed from the original partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein by ligand exchange chromatography on columns containing Chelex 100 (Biorad, California) in complex with copper ions. The theoretical aspects of this method have been described by Helfferich(1961), and its application to separation of free amino acids from oligopeptides by Buist & O'Brien (1967) and Asatoor, Milne & Walshe (1976). Peptides were eluted from the column with borate buffer (0.1 mol/l), pH 11, and collected at 0°C with sufficient hydro- chloric acid (1 mol/l) to neutralize the buffer. Copper ions were removed from the column eluate with a methanolic solution of sodium diethyl dithiocarbamate (Fazakerley & Best, 1965). The resulting solution containing the peptide moiety of the hydrolysate was subjected to complete acid hydrolysis and ion-exchange chromatography to quantify the peptidebound amino acid content of the original casein hydrolysate. The column eluate, after removal of copper ions and before acid hydrolysis, was also examined by ion-exchange chromatography to check that complete removal of free amino acids had been achieved. Free amino acids in the native casein hydrolysate were estimated by ion-exchange chromatography of the whole hydrolysate. Perfusion procedure Normal subjects (medical students and laboratory personnel) gave informed consent to the study. A double-lumen perfusion tube incorporating a proximal occlusive balloon (Silk, Perrett & Clark, 1973), was positioned under radiological control with the 30 cm perfusion segment in the upper jejunum. Perfusion solutions were pumped through the infusion orifice at 20 ml/min with a peristaltic pump (H.R. Flow Inducer, Watson-Marlow Ltd, Marlow, Bucks, U.K.) from bottles maintained at 37°C in a water bath. A 30 min equilibration period was allowed for the attainment of steady-state absorptive conditions for each solution before collection of three consecutive 10 min samples from the distal orifice. Seven subjects (two female and five male; aged 21-28 years) were perfused with the enzymic hydrolysate of casein at a concentration of 24.9 mmol of a-amino nitrogen/] (determined after acid hydrolysis) alone, and also in the presence of glycylglycine (100 mmol/l). Six further subjects (four female and two male, aged 21-26 years) were perfused with the amino acid mixture alone, and also in the presence of glycylglycine (100 mmol/l). Solutions, which were perfused in random order, were adjusted to pH 7 by titration with sodium hydroxide (1 mol/l), contained the non-absorbable marker polyethylene glycol (2.5 g/l) labelled with 1 pCi of [14C]polyethylene glycol/l, and were made iso-osmotic (285-295 mmol/kg) by adding sodium chloride. Absorption of amino acids from human jejunum Glycylglycine was obtained from the Sigma (London) Chemical Co. Ltd, the purity being checked before perfusion with an amino acid analyser. Analyticalmethods and calculationof results TO measure absorption of individual free plus peptide-bound amino acids from the hydrolysate and amino acid mixture, samples of the perfusion solutions and their respective intestinal aspirates were hydrolysed under identical conditions in sealed glass tubes with HCl (6 mol/l) at 110°C for 24 h. Amino acids were estimated by ion-exchange chromatography with a Locarte Automatic Loading Amino Acid Analyser (mark 4 Floor model, The Locarte Co., London, W.14). In solutions subjected to acid hydrolysis the amides of the dicarboxylic acids (glutamine and asparagine) were converted into glutamic acid and aspartic acid and were measured as such. '*C radioactivity was measured with a scintillation counter [Corumatic 2000 with Diehl Combitron S Computer; ICN Pharmaceuticals (UK) Ltd, Tracerlab, Hersham, Surrey, U.K.] by the procedure described by 29 Wingate, Sandberg & Phillips (1972) and Silk, Perrett, Webb & Clark (1974). The osmolality of perfusion solutions was checked immediately before perfusion with an Advanced Osmometer (Advanced Instruments Inc., U.S.A.). Percentage amino acid absorption is the amount of each amino acid disappearing from the perfused intestinal segment in unit time expressed as a percentage of the perfused load of that amino acid. The significanceof differences in percentage absorption of individual amino acids was assessed by the paired t-test (Snedecor, 1937). Results Composition of the partial epzymic hydroijwate of casein (Table 1) The mean recovery of amino acids from the enzymic hydroIysate of casein was 92%, as estimated from the sum of the free amino acids determined by chromatography of the native hydrolysate and analysis of the peptide-bound amino acids. This method may give a falsely low result from unavoidable loss of some peptide-bound amino acids during column TABLE 1. Composition of perfusion solutions N = not measured. Partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein Histidine (His) Lysine (Lys) Arginine (Arg) Aspartic acid (Asp) Asparagine (Am) Threonine (Thr) Serine (Ser) Glutarnic acid (Glu) Glutamine (Gln) Proline (Pro) Glycine (GIy) Alanine (Ma) Valine (Val) hfethionine (Met) Isoleucine (IIe) Leucine (Leu) Tyrosine (Tyr) Phenylalanine @he) Cystine (Cys) Tryptophan (Try) Amino acid mixture (mmol/l) Amino acid content as free amino acids (%) Amino acid in peptide form 0.6 I .4 0.6 69 56 71 31 44 29 E} 2.0 20 80 41 2.5 39 59 61 17 83 28 50 53 65 60 50 47 35 40 43 45 24 17 34 N z} 08 1.o 1.6 06 1.2 2.0 09 1.0 02 02 51 55 76 83 66 N N (%I N P. D. Fairclough et al. 30 separation (Asatoor et al., 1976). Consequently, the proportions of each amino acid present in the peptidebound and free forms in the casein hydrolysate (Table 1) are expressed as percentages. Approximately 50% of the total amino acids present in the hydrolysate were peptide-bound. The proportion of individual amino acids in the form of peptides varied: for example, 83% of the glutamic acid+ glutamine in the hydrolysate was peptidebound, in contrast to only 17% of the tyrosine. Absorption of amino acid residues from partial hydrolysate and equivalent amino acid mixture The perfusion experiments (Table 2) showed that there was considerable variation in the extent to which ihdividual amino acids were absorbed from both solutions; leucine, isoleucine, tyrosine and arginine were well absorbed, but aspartic acid asparagine, threonine, histidine and glycine were relatively poorly absorbed. Mean rates of absorption of all amino acid residues from the free amino acid mixture were less when glycylglycine (100 mmol/l) was included in the perfusion solutions (Table 2). By the paired t-test (five degrees of freedom) the differences were only significant for aspartic acid asparagine, threonine, serine, glutamic acid, proline, alanine, isoleucine and phenyl- + + + alanine. However, serine and glutamic acid glutamine were the only amino acids whose absorption from the partial enzymic hydrolysate was significantly inhibited when glycylglycine (100 mmol/l) was included in these perfusion solutions (Table 2). Hydrolysis of perfused glycylglycine The concentrations of glycylglycine and free glycine found in the intestinal aspirates during perfusion of the amino acid mixture and hydrolysate in the presence of glycylglycine (100 mmol/l) are shown in Table 3. The same concentrations of glycylglycine and free glycine were found in the intestinal aspirates when glycylglycine was perfused with the amino acid mixture and with the hydrolysate. Discussion The analysis of the partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein suggests that a proportion of all the amino acids present was in the peptide-bound form. The experiments thus test the effect of glycylglycine on the absorption of amino acids from a diverse mixture of small peptides and free amino acids. This is a marked difference in experimental design from the studies in vitro of Addison et al. (1974, 1975) and Das & Radhakrishnan (1975), who demonstrated the TABLE 2. Percentage absorption of amino acid residues from an amino acid mixture and a partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein in the absence and presence of glycylglycine (100 mmolll) Mean values f s e ~ are shown.NS = not significant. ~ Amino acid mixture (n = 6) Amino acid His LYs -b ASP Thr Ser Glu Pro G~Y Ala Val Ileu Leu Tyr Phe Alone P 40.1k 7.0 46.22 5.0 65.3 2 7.9 42.2+43 40.12 3.1 48-3+29 43.6k4.2 53.8k7.2 162+ 8 7 51.1k4.8 58-4+ 4 4 725k7.4 72.8-1-7.8 6 4 4 2 8-0 59.0+ 6.2 NS NS NS < 0.01 < 0.025 < 002 < 0.025 < 0.001 - < 0.02 NS < 005 NS NS < 0.05 ~ ~~~~ Partial enzymic hydrolysate (n = 7) With glycylglycine 17.8f7.1 32.1 f8.0 41.92 11.0 18-628.5 6.8+ 11.3 25-4+ 5.6 19.3k7.4 21.1k4.8 - 31.6k4.5 36.2f 144 4 0 5 k 13.1 42.6+ 13.6 4 0 6 2 109 38.8 7.9 + Alone 42-lt8.8 42.1 f 6-0 49.6f 9.1 47.1 f 8.1 37.35 7.1 47226.1 34.3+ 6.5 49.1 2 8.0 3 4 8 2I04 53.1 1 6 . 8 54.6+ 8.8 65.41 7.7 63.5+ 6.6 63-8k7.6 524+9-2 P With glycylglycine NS 31-2f8.0 37.9+3-7 56.2f 3.8 342+ 4 2 24.9 4-1 33*5+ 3.9 17.1k5.2 38.1 f 6.3 NS NS NS NS NS NS 51.1 k 4.3 58.0+ 2.8 63-7+ 3.4 63.5k 2.9 55.4+ 4.8 546+ 2 6 NS NS NS NS NS < 0.01 < 0.01 - - Absorption of amino acids from himan jejunum 31 TABLE 3. Concentrations offree glycine and glycylglycine in intestinal aspirates during perfusion of glycylglycine (100 mrnolll) with amino acid mixture or hybolysate Concn. in aspirates (mmol/l) Free glycine G1ycylglycine Glycylglycine Glycylglycine Glycylglycine +amino acid mixture 12-8 11.7 23.8 21.1 7.7 14.8 18-2 15.2 16.1 15.7 17.8 15*7+0-7 54.3 18.2 55.7 16.1 78.7 +amino acid mixture +hydrolysate Mean 16.8k2.8 effects of a number of individual peptides on absorption of single model peptides. The results of the perfusion experiments were unexpected, so that further studies are needed to estimate the quantitative importance of peptide uptake by this type of experiment. Glycylglycine had a marked inhibitory effect on absorption from the free amino acid mixture (Table 2). This was an unexpected result, since separate transport sytems are thought to be involved in the mucosal uptake of peptidebound and free amino acids (Rubino et al., 1971; Addison et al., 1974, 1975; Das & Radhakrishnan, 1975; Matthews, 1975). Table 3 shows, however, that in the present perfusion experiments in uivo appreciable amounts of the dipeptide glycylglycine are absorbed in the free form, as 16.8 and 15.7 mmol/l of free glycine was detected in the luminal fluid when glycylglycine (100 mmol/l) was included in the perfusion solutions containing the amino acid mixture and hydrolysate respectively. As the concentration of individual free amino acids in the amino acid mixture ranged from only 0.2 to 2.8 mmol/l (Table l), inhibition of neutral amino acids by the observed concentrations of free glycine is to be expected. Likewise, the observed inhibition of glutamic acid and aspartic acid absorption is not altogether unexpected, as absorption of these amino acids may be inhibited by neutral amino acids (Matthews, 1975) and both have been shown to share the transport system used for another neutral acid (Nathans, Tapley & ROSS,1960). Unfortunately, since neither the brush-border nor cytoplasmic peptidase activities of the perfused mucosa could be measured, we could 607+4-8 Glycylglycine +hydrolysate 52.2 41.6 37.5 59.8 68.6 60.3 53.1 k 4-1 not determine the source of the free glycine liberated during perfusion of glycylglycine. Quite unexpectedly, however, absorption of only two amino acids (glutamic acid fglutamine and serine) from the partial enzymic hydrolysate of casein was significantly inhibited when glycylglycine (100 mmol/l) was included in the perfusion solutions. Recent studies indicate that peptides may be either absorbed intact or hydrolysed at the brush-border membrane of the cell, with subsequent absorption of the free amino acids by the normal amino acidtransport mechanisms (Cheng, Navab, Lis, Miller & Matthews, 1971;Matthews, Crampton & Lis, 1971;Silk et al., 1974;Silk, Nicholson & Kim, 1976). One explanation for the lack of effect of glycylglycine on absorption of amino acid residues from the hydrolysate could therefore be that at the concentrationstudied the peptides of the hydrolysate were all absorbed as free amino acids. However, one would then expect inhibition of absorption of the same amino acids from both the mixture of free amino acids and the hydrolysate, which did not OCCW. Our study was designed on the assumption that there is only a single peptide-transport system in mammalian small intestine, as suggested by Das 8c Radhakrishnan (1975). Another explanation for our findings may be that this assumption is not valid for human small intestine in vivo. The observations that absorption of aspartic acid, threonine, proline, alanine, isoleucine and phenylalanine from the hydrolysate was unaffected by either the free glycine in the lumen (which as discussed above, probably inhibited absorption of these amino 32 P . D . Fairclough et al. acids when presented in the free form), or by glycylglycine, which has been shown to inhibit absorption of several di- and tri-peptides in vitro (Rubino et al., 1971; Addison et al., 1974; Das & Radhakrishnan, 1975), might be explained if these amino acid residues were absorbed by an alternative peptide transport system which was not shared with glycylglycine. There are 400 possible dipeptides, so that our results cannot with certainty be extrapolated to the normal biological state. Moreover, if there is more than one peptide-transport system, the quantitative importance of peptide transport during absorption of protein-digestion products cannot be determined by studies such as this which investigate the inhibitory effect of a single peptide. One reason for the lack of inhibitory effect of glyclylglycine could be that this dipeptide is a relatively weak inhibitor of peptide transport. Indeed, Das & Radhakrishnan (1975) have suggested that glycylglycine does have an unusually low affinity for the transport system used by glycyl-leucine. Nonetheless, glycylglycine significantly inhibits absorption of several dipeptides in uitro (Rubino et al., 1971;Addison et af., 1974, 1975). Furthermore, in the present study the mean total concentration of peptide derived from the partial enzymic hydrolysate in the intestinal lumen was not more than 5 mmol/l, whereas the mean luminal concentration of glycylglycine was about 75 mmolll. It thus seems unlikely that the lack of inhibition observed was solely due to insufficient saturation of the peptide-transport system by the inhibitor peptide. Finally, the above studies in which glycylglycine was shown to inhibit absorption of other di- and tri-peptides (Rubino et al., 1971; Addison et al., 1974; Das & Radhakrishnan, 1975) were all performed in vitro. This inhibitory effect may be due to competition for an energy source which does not occur in uivo, again emphasizing the difficulty of comparing experimental data on peptide absorption in uiuo and in uitro (Silk & Kim, 1976). Acknowledgments We are grateful for financial support to the Medical College and Joint Research Board of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, the North-East Thames Regional Health Authority and to the Medical Research Council (for a grant to D.M.M.). We also thank Dr A. M. Dawson for constructive criticism and for the use of his laboratory facilities. References ADDISON,J.M., BURSTON,D., DALRYMPLE, J.A., MATTHEWS, D.M., PAYNE,J.W., SLEISENGER, M.H. & WILKINSON, S. (1975) Competition between the tripeptide glycylsarcosylsarcosine and other di- and tri-peptides for uptake by hamster jejunum in vitro. Clinical Science and Molecular Medicine, 49, 3 13-322. ADDISON,J.M., MATTHEWS,D.M. & BURSTON,D. (1974) Competition between carnosine and other peptides for transport by hamster jejunum in vitro. Clinical Science and Molecular Medicine, 46,707-714. ADIFJI,S.A. (1971) Intestinal transport of dipeptides in man; relative importance of hydrolysis and intact absorption. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 50, 2266-2275. ADIBI,S.A. & MERCER, D.W. (1973) Protein digestion in human intestine as reflected in luminal, mucosal and plasma amino acid concentrations after meals. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 52, 1586-1594. ADIFJI,S.A. & SOLEIMANPOUR, M.R. (1974) Functional characterisation of dipeptide transport system in human jejunum. Journal of Clinical Inuestigation, 53, 1368-1374. ASATOOR, A.M., MILNE,M.D. & WALSHE, J.M. (1976) Urinary excretion of peptides and of hydroxyproline in Wilson’s disease. Clinical Science and Molecular Medicine, 51, 369-378. BUNT,N.R.M. & O’BRIEN,D. (1967) The separation of peptides from amino acids in urine by ligand exchange chromatography. Journal of Chromatography, 29, 398-402. CHENG,B., NAVAB,F., LIS, M.T., MILLER,T.N. & MATTHEWS, D.M. (1971) Mechanisms of dipeptide uptake by rat small intestine in uitro. Clinical Science, 40,247-257. CLEGG,K.M. & MCMILLAN,A.D. (1974) Dietary enzymic hydrolysates of protein with reduced bitterness. Journal of Food Technology, 9,21-29. DAS,M. & RADHAKRISHNAN, A.N. (1975) Studies on a wide-spectrum intestinal dipeptide uptake system in the monkey and in the human. Biochemical Journal, 146,133-139. FAZAKERLEY, S. & BEST,D.R. (1965) Separation of amino acids as copper chelates from amino acid, protein and peptide mixtures. Analytical Biochemistry, 12,290-295. HELFFERICH, F. (1961) ‘Ligand exchange’: a novel separation technique. Nature (London), 189, 10011002. HELLIER,M.D., HOLDSWORTH, C.D., MCCOLL,I. & PERRETT, D. (1972) Dipeptide absorption in man. Gut, 13,965-969. MATTHBWS,D.M. (1975) Intestinal absorption of peptides. Physiological Reviews, 55, 537-608. MAITHEWS,D.M., CRAFT,I.L.. GEDDES.D.M., WISE, I.J. & HYDE, C.W. (1968) Absorption of glycine and glycine peptides from the small intestine in the rat. Clinical Science, 31, 751-164. MATTHEWS, D.M., CRAMPTON, R.F. & LIS,M.T. (1971) Sites of maximal intestinal absorptive capacity for amino acids and peptides: evidence for an independent peptide uptake system or systems. Journal of’ Clinical Pathology, 24, 882-883. Absorption of amino acids from human jejunum MATTHEWS, D.M., LIS, M.T., CHENO,B. & CRAMPTON, R.F. (1969) Observations on the intestinal absorption of some oligopeptides of methionine and glycine in the rat. Clinical Science, 37, 751-764. D.F. & Ross, J.E. (1960) NATHANS,D., TAPLEY, Intestinal transport of amino acids; studies in uitro with ~-[~~~I]monoiodotyrosine. Biochimica et Biophysics Acza, 41,271-282. H. (1971) RUBINO,H., FIELD,M. & SCHWACHMAN, Intestinal transport of amino acid residues of dipeptides. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 246, 3542-3548. SILK,D.B.A. (1974) Absorption of peptides in man. M.D. thesis, University of London. SILK, D.B.A., CLARK,M.L., MARRS,T.C., ADDISON, D.M. & CLEGG, J.M., BURSTON,D. MATTHEWS, K.M. (1975) Jejunal absorption of an enzymic hydrolysate of casein prepared for oral adrninistration to normal adults. British JournaZ oflvutrition, 33, 95-100. SILK,D.B.A. & KIM, Y.S. (1976) Release of peptide hydrolases during incubation of intact intestinal 33 segments in vitro. Journal of Physiology (London), 2S8.489-491. -_ -, .- . ... . SILK, D.B.A., NICHOLSON, J.A. 8c KIM, Y.S. (1976) Relationships between mucosal hydrolysis and transport of two phenylalanine dipeptides. Gut, 17, 870-876. SILK, D.B.A., PERKETT,D. & CLARK,M.L. (1973) Intestinal transport of two dipeptides containing the same two neutral amino acids in man. Clinical Science and Molecular Medicine, 45, 291-299. SILK, D.B.A., PERRETT,D., WEBB,J.P.W. & CLARK, M.L. (1974) Absorption of two tripeptides by the human small intestine: a study using a perfusion technique. Clinical Science and Molecular Medicine, 46,393-402. SNEDECOR, G.W. (1937) Statistical Methods. Iowa State Medical College Press, Ames, Iowa. WINOATE,D.L., SANDBERG, R.J. & PHILLIPS,S.F. (1972) A comparison of stable and 14C-labelled polyethylene glycol as volume indicators in the human jejunum. Gut, 13,812-815.