* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Story of the Wissahickon Rocks Tienne Moriniere

Survey

Document related concepts

Provenance (geology) wikipedia , lookup

Large igneous province wikipedia , lookup

Tectonic–climatic interaction wikipedia , lookup

Age of the Earth wikipedia , lookup

History of geology wikipedia , lookup

Composition of Mars wikipedia , lookup

Marine geology of the Cape Peninsula and False Bay wikipedia , lookup

Clastic rock wikipedia , lookup

Algoman orogeny wikipedia , lookup

Geology of Great Britain wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

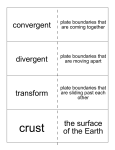

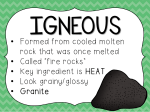

Myers, 1 SCIENCE CONTENT: The Story of the Wissahickon Rocks Tienne Moriniere-Myers Introduction: The purpose of this project is to design resources, for use in a middle school science class, presenting Wissahickon Schist as a way of understanding metamorphism, while gaining an appreciation for geological features in the local region. The first section of the project is to provide information about the amazing rocks that are located in Philadelphia and to understand the recipe that caused them to become became part of our geologic landscape. The second section of this project will provide strategies to teach students about the rock cycle and metamorphism. It will tackle student misconceptions and focus on enduring understandings. When you examine a rock you can learn a great deal about its origins and geological history. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago. Unfortunately, there are no rocks remaining on Earth from this part of Earth’s early geological history, but the rocks that do exist on Earth give us clues to interpret what happened in the past. The rocks found in the Wissahickon Valley tell us the amazing geologic story of Philadelphia. Background: Geological Time Since the beginning of the 1700’s, scientists have agreed that some rocks are older than others. A time chart, the geologic time scale, was developed to categorize rocks according to their ages based on methods of relative dating. Since 1949 geologists have been able to date rocks by radioactive elements. The breakdown or decay of atomic nuclei is known as radioactive decay. As radioactive parent atoms decay to their stable daughter atoms (i.e., uranium decaying to lead), there is one more atom of the daughter than was initially present, and one less atom of the parent. The time required for one-half of the original number of parent atoms to decay is the half-life, which is related to the decay constant (Lutgens and Tarbuck, 2006). Knowing the half life, one can determine the absolute age of a rock based on the ratio of the parent to daughter isotopes in the rock. 1 Myers, With these dates, geologists have been able to time scale. 2 assign absolute ages on the geological The following chart shows the divisions of geologic time and their corresponding ages. Figure 1 The Geological Time Scale divides Earth’s geologic history into distinct intervals of time. http://3dparks.wr.usgs.gov/bigbend/images/timescale.jpg&imgrefurl Plate Tectonics An observant meteorologist, Alfred Wegner, noticed how neatly the eastern American coast fits against the western coast of Africa and Europe. His hypothesis, called continental drift, was published in 1915. He postulated that a supercontinent called Pangaea existed and broke apart leading to Earth’s current configuration of continents. 2 Myers, 3 His ideas and concepts were based on some very convincing observations. Wegner noticed, and confirmed his findings with the paleontological literature, that identical fossil organisms were found in both the South American and African continents, including organisms that had no ability to swim across such a mass of water (Erickson, 2001). The classic example of this is the Mesosauris He also noticed the close fit between the coastlines of Africa and South America. However, his jigsaw fit of the continents was very crude, and he did not provide a convincing mechanism for how and why the continents moved (Tarbuck and Lutgens, 2006). After World War II, studies of the seafloor led to the discovery of a global oceanic ridge system winding through all of the major oceans in a manner similar to the seams of a baseball (Lutgens and Tarbuck, 2006). The observation of this topographical feature and its connection to alternating bands—each band magnetized with a polarity opposite the surrounding bands—of seafloor led to the understanding of seafloor spreading (the process by which new oceanic crust is formed at mid-ocean ridges through volcanic activity and then slowly moved away from the ridge). Seafloor spreading helps to explain how the continents drift in the paradigm of plate tectonics (Erickson, 2001) Plate tectonics is the ultimate framework into which observations of North American geologic history fit. The paradigm of Plate Tectonics states that Earth’s crust is composed of a rigid layer known as the lithosphere, which is broken into pieces called plates (Erickson, 2001). There are seven major lithosphere plates: North American, South American, Pacific, African, Eurasian, Australian-Indian, and Antarctic. These plates rest on a region in the mantle known as the asthenosphere. The asthenosphere is composed of rocks that are near their melting temperature. The result is a very weak zone that allows the lithosphere to detach from the layers below. The weak rock within the upper asthenosphere allows the Earth’s rigid outer shell to move. The theory is also based on the fact that mid-ocean ridges and trenches border these plates, and the crust is moving under the power of convection in the mantle below. The theory explains how we can look at rocks today and conclude their past and predict their future (Lutgens and Tarbuck, 2006). 3 Myers, 4 The Plate Tectonic History of the Wissahickon Valley: The Paleozoic Orogenies of the Central East Coast of North America. Three important Paleozoic orogenies that helped to shape the region we now call Eastern North America occurred between 500 and 250 million years ago. During this time, rocks show evidence of continental plates combining to form the supercontinent Pangaea. After these events, a divergent plate boundary developed and opened the ocean we today call the Atlantic. Precambrian rocks show that continental rifting and collisions of this kind have been occurring for over two billion years and likely Earth’s entire 4.5 billion year history (Roberts, 2006). The Rocks of the Wissahickon Through Geological Eras Since the Precambrian, margins of what was to become the east coast of North America have been very active geologically. Geologists hypothesize that during the Precambrian Eon the region we now refer to as the Wissahickon Valley was in its nascent stage, forming as shale and sandstone deposits on the floor of the Iapetus Ocean. At some stage in the late Ordovian era, materials from the Ocean floor were thrusted onto the eastern coast of the proto-North American plate. This was called the Taconic orogeny, and this event caused the development of mountains in Pennsylvania. At the end of the Devonian Period another collision took place. A crash of the eastern North American coastline and Europe caused the Acadian orogeny, another large mountain building event. Once these mountains were formed, deposits of black and gray shale must have covered the eastern part of Pennsylvania as once again it was inundated with water. Ultimately, the Acadian mountains eroded causing more sediment to be created. There was no more marine water in this area after this time period. The Permian Period saw another major collision of North America. This collision is known as the Appalachian orogeny. This was the collision of North America and Africa. The supercontinent of Pangaea was formed (Roberts, 2006). During each of these collisions larger and larger mountains were formed and the shale and sandstone deposits originally deposited during Precambrian time in the ancient 4 Myers, 5 Iapetus Ocean were further buried and metamorphosed. A very large mountain range, similar in scale to the Himalyas today must have existed along the East Coast of North America, with the schist and quartzite (products of metamorphosing the shale and sandstone) buried deep within. These mountains were eventually eroded over the last 200 million years, since Pangaea has split apart, and the sediments eroded from this mountain range now lie in the Atlantic Ocean. A vast amount of material eroded in these 200 million years. The time and the amount of material eroded seems massive beyond our imagination, but this is just a small percentage of geological time; 200 million years is less than 5% of Earth’s history! With the mountains now eroded, the Piedmont Province of Pennsylvania where the Wissahickon Valley is located is now exposed at the surface, and with it the beauty of its sparkling schist, sturdy quartzite and myriad pegmatite intrusions (West, 1998). The Rocks of the Wissahickon Valley: The Rock cycle Rocks are classified in three main categories: Igneous, Sedimentary and Metamorphic. They are classified according to how they are formed. Igneous rocks or “fire rocks” form when magma or molten rock cools and solidifies. This process is called crystallization. This may happen above the Earth’s surface after the eruption of a volcano or beneath the Earth’s crust. Igneous rocks are found at the surface and endure weathering. Then, they slowly disintegrate. The particles that are created are affected by gravity and slowly move downhill. These sediments can be transported by water, glaciers, or wind. Eventually these particles, called sediments, are deposited. Most sediments end up in the ocean. Other sites of deposition are desert basins, river flood plains, sand dunes and swamps. These sediments convert into rock through the process of lithification. This takes place when sediments are compacted by the weight of overlaying layers or cemented as percolating ground water fills the pours with mineral matter. The result is sedimentary rock. Sometimes the resulting sedimentary rock becomes buried deep inside the Earth. This rock can be part of a mountain building or intruded by a mass of magma. It will then be confronted by great pressure, intense heat, chemically active fluids, or a combination of all three. The sedimentary rocks will 5 Myers, 6 react to this new environment and turn into metamorphic rock. Rocks are constantly undergoing changes, which take a great deal of time. The movement of material from one type of rock to another is explained by the rock cycle, as shown in figure 2 below (Lutgens and Tarbuck, 2006). Figure 2 http://images.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://gpc.edu/~pgore/Earth. Metamorphism Metamorphic rock begins with pre-existing sedimentary, igneous, or older metamorphic rock. Heat and pressure cause the rock to change. Depending on the temperature and amount of pressure the rock is exposed to, a different amount of metamorphism will occur. Due to the extreme heat and pressure that exists beneath the surface of Earth, metamorphic rock can be found deep below the surface. Most of the Earth’s crust is composed of metamorphic rock. Another way this rock can form is when a rock is in contact with magma and is “baked.” This type of metamorphism is termed contact or thermal metamorphism. The movement of heat by convection in the mantle, 6 Myers, 7 which leads to Plate Tectonics, is the ultimate cause of metamorphism. The plates move and have boundaries that cause different interactions. Collisions at convergent boundaries cause great heat and pressure, which can result in metamorphism (Lutgens and Tarbuck, 2006). The Paleozoic Orogenies described above were initiated by Continental-Continental collisions (when two continental plates collide) and are the cause of the rocks that are found in the Wissahickon. Wissahickon Schist and Quartzite The schist and quartzite rocks fond in the Wissahickon Valley started as sedimentary deposits that washed off of an ancient continent. Water carried these sediments and they collected at the margins of the continents. This ancient mud and sand compressed into shale and sandstone, respectively. Long periods of mountain building caused the rocks to experience great heat and pressure. The rocks went through the process of metamorphism and became schist and quartzite (West, 1998). The interbedded schist and quartzite in the Wissahickon Valley indicate that the original shale and sandstone was likely deposited in a nearshore environment, close enough to a continental shelf to periodically have accumulations of sand from turbidity currents. Large grained sandstones (the parent rock of the quartzite) are not typically deposited farther from a continental shelf in a deep ocean setting (West, 1998). During the metamorphic process, the original shale and sandstone experienced high temperature and pressure changes that caused chemical changes. These differences in temperature and pressure caused atoms to regroup by diffusion into new crystal configurations producing muscovite and biotite micas, quartz, chlorite, garnet, staurolite, tourmaline, kyanite and sillimanite, among others. Chlorite, biotite, garnet, staurolite, kyanite and sillimanite are known as index minerals because they indicate the temperature and pressure that the minerals experienced during metamorphism. (The other minerals, including muscovite, feldspar and quartz are not as indicative of particular conditions.) “For example biotite begins to form at about 400C; garnets at around 500C: and kyanite around 600C while sillimanite require temperatures over 600C.” (West,1998) 7 Myers, 8 To understand the sequence of index minerals, geologists use the Barrovian sequence of index minerals (Figure 3). The sequence in Wissahickon schist is biotite, garnet, staurolite, kyanitye, and sillimanite, which indicates that there was an increase of temperature during metamorphism. Sillimanite and kyanite are only formed at depths of about 20-25 kilometers so scientists know that the shales and sandstones that metamorphosed into the schist and quartzite of the Wissahickon must have been buried at least 20 km below the surface(West, 1998). This means that in order for us to walk over them today, 20-25 kilometers of rock must have been eroded away! Figure 3 The Barrovian Sequence http://csmres.jmu.edu/geollab/Fichter/MetaRx/Images/phasebarrov.gif Pegmatite can also be found in Wissahickon schist. Pegmatite is a coarse-grained igneous rock that is made up of large crystals and often contains uncommon elements. The pegmatite indicates that hot magma intrusions intruded the spaces and cracks as the schist and quartzite cooled. The large feldspar crystal size found in Wissahickon pegmatite indicates a high content of water in the magma (West, 1998). 8 Myers, 9 Taking a walk through the Wissahickon The 1800 acres of the Wissahickon Valley Park are part of the Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. This park is one of the largest parks in the world. It is a very scenic and wooded valley that has a creek, known as the Wissahickon Creek running through the seven-mile length. I have lived in this area of Philadelphia, for over fifty years but until the summer of 2007, I never knew the gems that are located 2 miles from my house. Dr. Jane Dmochowski, a Geophysicist at the University of Pennsylvania introduced my Earth Science class to the Geology of the Wissahickon, by giving us a guided tour. We started our exploration at a landmark called the Valley Inn in a section of the park known as Valley Green. We observed how some of the rocks had alternating layers of schist and quartzite contained within them. The schist is the layer that scratches easily and contains observable layers (foliation). The schist layers contain garnet and mica. Furthermore, the schist has tiny waves within its layers called crenulations, which makes the rock look crinkled. Looking at schist very closely helps the observer decode past geologic events (West, 1998). One of the most beautiful features of the Wissahickon Schist are the garnet crystals found throughout the rock. Garnets are a crystalline silicate mineral, usually dodecahedron (meaning they have 12 crystal faces), that are commonly found in metamorphic rocks. The garnets indicate the temperature and pressure the rocks experienced during metamorphism. There is also a presence of iron compounds in the rocks at this site, as indicated in the outward rusted look on newly broken rocks (West, 1998). Many of the schist and quartzite outcrops throughout the valley display examples of conjugate joint sets. The cracking occurred when the rocks were under stress at a cooler stage than when they were metamorphosed, when they reacted rigidly, rather than flowing in a ductile manner as they would have at greater temperatures. These cracks are called joints. You can also observe the effects of weathering on schist, indicated by the dark color (West, 1998). 9 Myers, 10 Some of the schist we observed has quartzite veins. Quartzite veins form within schist if superheated steam carrying dissolved silicates flows through a crack within the schist while it is still deep in the ground. (West, 1998) We also observed intrusions of pegmatite in the schist. They appear as bands of wavy, white material, mostly quartz and feldspar, that permeate through the rock. As the original schist layers formed they were compressed. Deep below, rock was melted and flowed upward due to its buoyancy, intruding and crystallizing between the morphed layers and schist and quartzite (West, 1998). The above observations are just a few of the fascinating aspects of the rocks that can be found in the Wissahickon Valley. Now that I have been introduced to the geology of this area, I look at the rocks in my world through different eyes. As I look around my neighborhood, I can see schist in constructions that I have been looking at for years. In other words, I have spent many years walking through the Wissahickon without knowing that these rocks had such an interesting story. The geology of this area of Philadelphia is an ideal site for my students to explore and study the story contained in metamorphic rock. 10 Myers, 11 References Dmochowski, J, (2007) The University of Pennsylvania Erickson, Jon, (2001). Plate Tectonics: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Earth New York: Checkmark Books Lawless, T. (2004). Giving the Wissahickon a Second Look Retrieved July, 2007 http://www.amcdv.org/pubs/footnotes/articles/wissahickongeology.sht Lutgens, K., and Tarbuck, E. (2006). Earth Science New Jersey: Pearson Education Friends of the Wissahickon, (2006) Retrieved July, 2007 http://www.fow.org/faqs.php Roberts, D. (1996). A Field Guide to Geology New York: Houghton Mifflin Company West, S. (2000) Journeys in Science, Gems in the Wissahickon, Pennsylvania Association of Environmental Education Journal 11