* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Glossary of Terms - Department of Natural Resources

History of geology wikipedia , lookup

Age of the Earth wikipedia , lookup

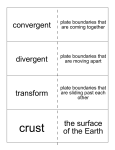

Great Lakes tectonic zone wikipedia , lookup

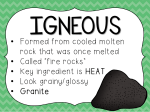

Large igneous province wikipedia , lookup

Ore genesis wikipedia , lookup

Sedimentary rock wikipedia , lookup

Geology of Great Britain wikipedia , lookup

Igneous rock wikipedia , lookup