* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing Roland Zs

Internal communications wikipedia , lookup

Market segmentation wikipedia , lookup

First-mover advantage wikipedia , lookup

Sales process engineering wikipedia , lookup

Social media marketing wikipedia , lookup

Bayesian inference in marketing wikipedia , lookup

Food marketing wikipedia , lookup

Product planning wikipedia , lookup

Affiliate marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Marketing channel wikipedia , lookup

Neuromarketing wikipedia , lookup

Sports marketing wikipedia , lookup

Target audience wikipedia , lookup

Youth marketing wikipedia , lookup

Ambush marketing wikipedia , lookup

Multi-level marketing wikipedia , lookup

Digital marketing wikipedia , lookup

Guerrilla marketing wikipedia , lookup

Viral marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing research wikipedia , lookup

Integrated marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Target market wikipedia , lookup

Advertising campaign wikipedia , lookup

Marketing plan wikipedia , lookup

Sensory branding wikipedia , lookup

Direct marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing mix modeling wikipedia , lookup

Multicultural marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing strategy wikipedia , lookup

Green marketing wikipedia , lookup

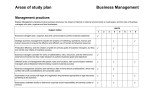

Int. J. Entrepreneurial Venturing, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2011 The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing Roland Zs. Szabo*, Lilla Hortovanyi, David F. Tarody, Adrienn Ferincz and Miklos Dobak Corvinus University of Budapest, Fovam ter 8, H-1093, Budapest, Hungary Fax: +36-1-482-5018 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract: This paper aims to explain how the two sources of knowledge (know-how, know-who) influence the use of innovative marketing techniques and their impact on competitive advantage. The proposition is studied through case-study methodology. Entrepreneurial behaviour is generally associated with the ability to innovate, initiate change, and perpetuate the strengths of flexibility and responsiveness. Consequently, entrepreneurial marketing managers also search for creating new opportunities by coming up with new combinations of the marketing tools, allocating resources in another way, or just looking at the value creation process from a different point of view. While conventional marketers use the traditional market research to adapt to the environment, entrepreneurial marketers rather build on experience, immersion, and intuition for making their decisions. Keywords: entrepreneurial marketing; guerilla marketing; knowledge; multi-case method; entrepreneurship; know-who; know-how. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Szabo, R.Zs., Hortovanyi, L., Tarody, D.F., Ferincz, A. and Dobak, M. (2011) ‘The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing’, Int. J. Entrepreneurial Venturing, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp.149–167. Biographical notes: Roland Zs. Szabo is an Assistant Professor at Corvinus University of Budapest and a Research Fellow at the Strategic and International Research Centre. He is the author and co-author of several research papers and book chapters about strategy and entrepreneurship. He also works as a Management Consultant for a variety of companies. Lilla Hortovanyi is an Assistant Professor at Corvinus University of Budapest. She holds an MSc in Business Administration and a PhD in Corporate Entrepreneurship. She was the Administrative Chair of the 23rd RENT International Conference organised in collaboration with the ECSB in November 2009. Besides her academic work, she is the Territory Manager of the Cisco Entrepreneur Institute in Hungary. David Tarody is a Research Assistant at the Strategic and International Research Centre. He is currently enrolled to the PhD programme of Business Administration at Corvinus University. As a graduate student he has been Copyright © 2011 Inderscience Enterprises Ltd. 149 150 R.Zs. Szabo et al. involved in several research projects, he was also the Winner of the Scientific Student Conference’s Strategic Management Track in 2010 at Corvinus University. Adrienn Ferincz is a Research Assistant at the Strategic and International Research Centre. She has been involved in the implementation of various research projects since 2009. She also works for Cisco Entrepreneur Institute as a Programme Manager. Miklós Dobák is the Head of the Institute of Management at Corvinus University Budapest. He has been the Director of the Department of Management and Organisation since 1989. He has published several books and articles in the field of management and organisation. 1 Introduction In the past few years, conventional marketing practices have been criticised. Among several other shortcomings, these criticisms questioned the over-reliance on established rules-of-thumb, formula-based thinking, the strong emphasis on promoting the four elements of the marketing mix, as well as the tendency to be imitative instead of innovative in marketing strategies (Morris et al., 2002). A solution to overcome these limitations might be the entrepreneurial approach to marketing, which embraces an entrepreneurial mindset in order to allow for a more sophisticated and efficient implementation of the marketing mix (Schulte and Eggers, 2010). Linking entrepreneurship with marketing leads us to the definition of Kraus et al. (2010) who describe entrepreneurial marketing as “an organisational function and a set of processes for creating, communicating and delivering value to customers and for managing customer relationships in ways that benefit the organisation and its stakeholders. According to their definition, entrepreneurial marketing is best understood as “marketing activities with an entrepreneurial mindset” (p.20). Knowledge is recognised as a crucial element of entrepreneurship (Mueller, 2005). It generates innovations and is capitalised by being transformed into new products, processes, and organisations. One of the misconceptions about the entrepreneurial mindset is that entrepreneurs are the wanderers of the business world; they make decisions based on pure intuition. By contrast, the ability to identify, assess and commercially exploit business opportunities demands the existence of knowledge and skills. The success of an entrepreneurial organisation lies in its willingness to accumulate knowledge. One reason for different degrees of entrepreneurial activity across firms might be due to the varying level of knowledge sources firms possess. Wickham (2006) has suggested that there exist different sources of knowledge. Some important sources of knowledge are product or service knowledge, market knowledge and technical knowledge. It is the conjunction of all these three sources that sets up industry-specific knowledge. Industry-specific knowledge, however, does not produce entrepreneurs on its own. It forms the basis of a competitive advantage only if it is supplemented with other sources of knowledge, like general business and people knowledge. If an entrepreneur with such knowledge were to be transplanted from one industry to another, the knowledge would still be valuable (Szabό, 2010; Wickham, 2006). The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 151 The framework developed in this paper aims to explain differences in entrepreneurial marketing activities due to variations in organisational knowledge. In their attempt to clarify the concept of entrepreneurial marketing, Kraus et al. (2010) called for empirical research, namely field experiments, participative observational research or narrative interviews, which all appear promising to conduct such exploratory research. Consequently, the aim of this paper is accomplished by the qualitative study of knowledge sources in four organisations from a single industry in order to support propositions empirically in a more accurate way. Actors within a single industry are confronted with the very same macroeconomic trends and industry forces. 2 Literature review 2.1 The link between entrepreneurial behavior and marketing An innovation is more than an invention of doing something in a new way. Innovation also includes an understanding of how a new product can be delivered to customers and how it can be promoted to them. Accordingly, innovation is a means of opportunity exploitation. Thus, organisational, financial and commercial activities are equally present. Entrepreneurial marketing has a relatively young literature, but it is constantly growing. The concept has started to come into focus as the research in entrepreneurship has highlighted important findings about marketing practices that also have improved the existing marketing knowledge (Gartner, 1994; Morris et al., 2002; Hills et al., 2008; Hansen and Eggers, 2010). Hills and Hultman (2006) regard entrepreneurial marketing as an interface between entrepreneurship and marketing, where the two disciplines share the same concepts, objectives and goal-oriented behaviour (Gartner, 1994). Entrepreneurs are often associated with generating change to destroy the economic equilibrium and through that open up new opportunities for themselves and for their followers as well. Morris et al. (2002) defined entrepreneurial marketing as the proactive identification and exploitation of opportunities for acquiring and retaining profitable customers through innovative approaches. In order to be able to perform innovatively in such a way, entrepreneurial behaviour is necessary. Entrepreneurial behaviour is generally associated with the ability to innovate, initiate change, and perpetuate the strengths of flexibility and responsiveness (Guth and Ginsberg, 1990). There are five generally accepted measures of entrepreneurship: autonomy, innovation, proactiveness, calculated risk-taking, and growth-orientation (Hortovanyi, 2009; Stevenson and Gumpert, 1985; Eggers, 2010). In addition, Timmons (1994) suggested that entrepreneurial behaviour is opportunity-driven, where the exploitation of the opportunity is led by a team with parsimonious resources. An entrepreneurial marketer is also expected to demonstrate similar attributes (Martin, 2009): be opportunity-driven, be innovative and proactive in using resources, and, of course, be reliant on social capital in exploiting opportunities. The present study assumes that managers differ in their skills and competencies to apply consciously marketing tools to the discovery, creation and exploitation of opportunities. There have been several studies examining and emphasising the role of innovative and creative solutions in marketing and communication techniques (Morris 152 R.Zs. Szabo et al. and Lewis, 1995; Gartner, 1994) in order to apply a more cost-efficient approach compared to classical advertising. Entrepreneurial marketing may take several forms, such as guerilla marketing, buzz marketing and viral marketing (Hill, 2009; Levinson, 1984) all standing for a variety of low-cost, high-impact marketing techniques that allow entrepreneurial managers to achieve wide-ranging results with an untypically low utilisation of resources (Rößl et al., 2009). Viral marketing can be achieved by the use of social networks, while buzz marketing refers to the use of word-of-mouth communication through media such as internet, e-mail, or cell phone networks (Schmengler and Kraus, 2010). 2.2 Knowledge sources The Austrian economics school viewed entrepreneurial activity as rooted in an economic system in which information is unevenly distributed across people (Shane, 2001) which leads to the rise of market opportunities. It is the possession of idiosyncratic information that leads to the existence and identification of entrepreneurial opportunities. Taking it one step further, the present paper proposes that entrepreneurial opportunities arise due to variations in the knowledge sources of organisations. In the case of small- and medium-size organisations, the success of a company is often largely dependent on the owner-manager (Hambrick and Mason, 1984). Barker and Mueller (2002) argue that managerial style and decision-making processes are influenced by the knowledge of the individual, which is built up from that individual’s earlier experiences and educational background. This view is similar to Johnson and Lundvall’s (2001) model that distinguishes four aspects of knowledge: know-what (knowledge about facts); know-why (knowledge about principles); know-how (consisting of the practical capability to execute specific activities); and know-who (who knows what and who knows what to do). These knowledge sources are grouped in such a way as to argue that managerial behaviour differs because of the difference in managers’ knowledge-base. Figure 1 Main knowledge sources Know-what – professional knowledge Know-who – people knowledge Know-how – managerial knowledge 2.2.1 Know-what Szabó (2010) argues that value creation requires the possession of both product and market knowledge, since the organisation must know the needs of customers and how to promote and deliver the offerings to the marketplace. The industry-specific knowledge, called know-what, however, is regarded as a threshold competence, especially in repeated-purchase industries, where customer satisfaction and loyalty are key to long-term success. In such industries, organisations simply cannot afford to lose customers due to dissatisfaction; i.e., by not providing adequate solutions to their problems. Customer loyalty secures the fixed income and the long-term existence of the firm. Consequently, those ventures which do not possess know-what knowledge is assumed to run out of business in the short-run. The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 153 2.2.2 Know-who Second, the relevance of external communication and the establishment of links with outside organisations have been widely noted for entrepreneurship. Byers et al. (1997) pointed out that entrepreneurship is embedded in a social context. The knowledge of local, direct and interpersonal contacts enables businesses to identify where to access the needed resources. In addition, the mobilisation of these resources is faster and more successful than otherwise. According to Harryson (2006) the interpersonal or interorganisational networks are the media through which actors gain access to a variety of resources held by other actors (Hoang and Antoncic, 2003). These networks allow the actor to increase knowledge creation and enhance innovation performance whilst reducing complexity. Tsui and Farh (1997), in their explanation of guanxi, which is the Chinese equivalent of know-who, also arrived at a similar conclusion: managers end up in a position of managing a whole series of interdependencies on customers, suppliers, bankers, accountants, regulators and staff, among others, in order to survive and grow. 2.2.3 Know-how The third source of knowledge which a firm can draw upon to develop a basis for competitive advantage is knowledge of general management; that is the know-how. Creating something new, improved, or competitive is not a straightforward task. Know-how refers to the special knowledge about doing things. This is the knowledge which enables a business to keep on track while focusing on opportunities at hand. An opportunity is exploited only when its commercial value is recognised, hence the constant reorganisation and recombination of resources in a more effective way; the organisation becomes more responsive to the needs of customers and so becomes quicker in offering them new solutions. Peterson and Berger (1971) argue that entrepreneurial firms are often found in hostile and dynamic environments. Miller (1982) also found that the more hostile, dynamic or heterogeneous the environment the higher the level of innovation. Katila and Shane (2005) also arrived at a similar conclusion when they found that low-competition, resource-rich, and high-demand environments tend to support only incremental innovations. Innovation capacity is rather greater in markets that are crowded, resource-poor, and small. This is so because when resources constitute a bottleneck in the course of opportunity exploitation of innovation is a must. Consequently, Hills and Hultman (2006) argue that entrepreneurial marketing managers also search for creating new opportunities by coming up with new combinations of the marketing tools, allocating resources in another way or just looking at the value creation process from a different point of view. While conventional marketers use the traditional market research to adapt to the environment, entrepreneurial marketers rather build on acquisition of new knowledge in form of know-who and know-how. 2.3 Small business marketing Innovation has a link to marketing behaviour through the formation and maintenance of material competitive differentiation (Morris and Lewis, 1995). Marketing’s role in 154 R.Zs. Szabo et al. innovation then is to provide the concepts, tools and infrastructure to close the gap between innovation and market positioning to achieve sustainable competitive advantages (Gartner, 1994). It is important to note, though, that innovation doesn’t only mean the development of new products or techniques but several aspect of marketing as well (Cummins et al., 2000). Such innovations are based on the need to adapt to the environment and keep or improve the position of the company in the given market, through combating competing products or engaging new customers (Simpson and Taylor, 2000). Earlier it has been argued that small and medium enterprises differ from large companies regarding their marketing strategies and tactics. SMEs must rely on their knowledge of specialised, relatively narrow product niches in order to succeed (Kraus et al., 2007). Researchers point out that the differences in their characteristics are derived from the fact that SMEs are not able to hire experts hence their qualifications are deficient (Moore et al., 1983; Gaedeke and Tootelian, 1980). This would suggest that SMEs have fewer opportunities than large companies; however, Hill (2001) says that they are able to generate competitive advantage because of their size. The marketing activity of small firms is inevitably restricted in its scope and activity because of their limited resources. This result in marketing that is simplistic, haphazard, often responsive and reactive to competitor activity (Carson and Cromie, 1989). Coupled with a dynamic environment, these limitations challenge SMEs, driving their need for efficient and effective innovation to capitalise on marketplace opportunities; innovative marketing provides a significant mechanism in this process (O’Dwyer et al., 2009). 2.4 Guerilla marketing Kraus et al. (2010) describe guerilla marketing as an attempt to achieve high-impact promotions with low utilisation of resources by acting like a guerilla. It means to be surprising, efficient and rebellious. It also tends to be simple. Guerilla marketing actions are often only one-time, limited in scope, and seldom repeatable (Campbell, 1985). The low need for resources makes guerilla marketing attractive to small and new ventures (Gruber, 2004). Small firms usually lack resources, and their marketing budget also tends to be rather limited; hence they are under pressure to offset these limitations by creative and unconventional solutions. Concluding from the abovementioned characteristics, guerilla marketing tactics are unexpected and unconventional and often call traditional marketing actions into question (Hill, 2009). However, this type of marketing also requires an awareness of the traditional marketing tools and a readiness to apply new ones, which can be combined in order to eventually form the most adequate marketing portfolio for the company. According to Levinson (1984), two things are necessary to execute the methods of guerilla marketing successfully: a quality product and some money. The former is definitely needed in order to provide value to customers. Without customers knowing about your product, however, it is very difficult to sell. Guerilla marketing is a relatively economical way to persuade potential customers to try or buy a product. Resource scarcity alone, however, cannot explain the growing use of guerilla marketing, especially in cases of medium and large firms. There are a number of examples from large firms that leverage entrepreneurial marketing in order to gain competitive advantage (see e.g., Miles and Darroch, 2006). The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 3 155 Methodology The aim of the present paper is to explain how the two dimensions of knowledge (know-how, know-who) influence the use of innovative marketing techniques as well as their perceived impact on a firm’s performance related to competition. In order to extend our understanding of entrepreneurial marketing, as well as to verify our assumptions about the difference in know-how and know-who of marketers, the case study method is used to reveal grounded theory. Present research is built on a multiple case design. Each case was carefully selected in order to predict constraining results for predictable reasons (Yin, 1994). 3.1 Practice-based research Maritz (2010) has attempted to integrate the theory with practice by incorporating the models of Morris et al. (2002) and Strokes (2000) with 15 practice-based initiatives and interpreted as practice theory. Based on their findings, 15 prominent marketing initiatives were identified that are used by entrepreneurs to enhance organisational growth, boost income and extend their reach of target markets. These initiatives embrace using online marketing activity and tools, knowing and dealing with the customers, thinking in an integrative way and being creative and flexible. Among the latest examinations, Kaya et al. (2010) conducted research focusing on musicians as entrepreneurs. Musicians live in a chaotic, turbulent environment; their work requires action and initiative (Pendergast, 2004). Investigating which musician discovers and exploits different types of opportunities in the emerging digital landscape, Kaya et al. (2010) categorised musicians in four groups according to their business orientation and the level of their experience and attitude towards online activity. As result of their research, they identified four types of musician entrepreneurs and the major differences in the way that musicians assess the role of music labels, usage of technology, fame, targeted audiences and fan engagement. They also elaborated a theory to better understand how musicians recognise and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities provided by social networks. 3.2 Sample and data collection As an initial testing of the know-how, know-who model, four SMEs are chosen (Table 1). Each firm in the sample is a professional dental firm that has been in business for at least five years, is managed by one or more owner-managers, and is wholly owned by Hungarians. The industry and location were carefully selected: each and every firm is located in the North Western region of the country, located in the same town, and hence assumed to have – in theory – an equal chance to reach the same market share. In fact, Hungarian dental services are very popular to a growing number of Western Europeans, especially from neighbouring countries. This is an important characteristic, since managers can decide whether they will stick to the local market or expand their market share by serving foreign customers. In addition, healthcare is argued to be a knowledge-intensive industry, which allows in-depth study of the different knowledge factors. 156 Table 1 R.Zs. Szabo et al. The summary of selected cases The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 157 The know-what factor – as mentioned earlier – is a must-have competence for healthcare professionals, hence each firm posses it. Firms are differentiated according to their competence of know-how and know-who skills. Theoretical sampling is employed; the cases were chosen to provide examples of polar types (Eisenhardt, 1989). The selected cases were required to possess, as clearly as possible, the characteristics of each category in the tested model. Selection of the companies for these case studies was based on the entrepreneurial competencies (know-how and know-who) of the organisations and our prior knowledge of these firms. The data collection in this study relied on face-to-face interviews with the business owners of the dental firms, direct observations of the organisations during the visitations (Yin, 1994) and examination of the homepage and other marketing tools of the firms. The interviews were conducted based on open questions about the industry, organisational characteristics, marketing activity, marketing tools employed, innovation in the organisation and the results of the operation. 4 The emergent cases 4.1 Case 1: the family business To test the segment with low knowledge of management and marketing, the authors arranged an interview with a small enterprise of low growth opportunity and weak marketing activity. The main resource of this organisation is the up-to-date professional knowledge (know-what). The owner of the enterprise is a specialist in dentistry: he perceives himself not as a manager-leader, but solely as a doctor. He doesn’t have advanced management skills or marketing knowledge and experiences. Consequently, he also disapproves the ‘business-approach’: His duty is not running the business, or monitoring the market trends and competition: “I’m a dentist, not a merchant. My job is to cure people and not to sell them products”. As the owner admitted, the venture is a small family business. The core organisational values are the long-term approach, quality, and trust. The building, which is also the home of the owner’s family, enhances this familiar atmosphere. The owner hasn’t got any growth objectives; the only intention is to develop the standard of the service. The long-term targets of this business are all personal: making a good living and having more free time. “We do not want to grow! We are satisfied with our current situation and that is enough for us”. The continuous upgrade of professional knowledge is core concern; however, it is basically expected threshold competence for the industry. “Our most important target is to maintain service standards, because it is necessary to remain competitive. The development of the industry is fast”. With regards of entrepreneurial orientation, the owner is rather a follower. He does not search for new growth opportunities; he is contended with consolidating the venture’s current position. Consequently, the venture has only a weak marketing activity: only a flyer is sent twice a year to existing customers. “We have a homepage, because everybody has one”. There aren’t any conscious ways to renew the consumer base, only the indirect method of word-of-mouth marketing. “I don’t think that marketing can be really effective. My way is to offer/sell a service delivering good quality. Due to this my patients recommend me and my services to their neighbours and friends. This is enough for me!” 158 R.Zs. Szabo et al. As for the strengths, the venture focuses on providing high-quality of service. Its connections to the market are weak; the company is focusing only on its existing consumer group. It can’t react to the changes and challenges of the market because of its weak and tight customer base, and it is incapable of performing radical changes and implementing innovations because lack of advanced management skills and the lack of knowledge of new opportunities all together keep the business in highly vulnerable position. 4.2 Case 2: the expert Partial awareness of marketing opportunities is the main characteristic of the expert enterprise, which possesses satisfactory management skills but inadequate marketing activity. This consciousness appears in the positioning and the development of the service, but this development is incremental and absolutely misses innovation and the search for new opportunities, so there is a lack of entrepreneurial approach. The company plays only a small role in the premium segment of the market. The overall target is to fit the demands of the premium consumers. The conscious, but slow, expansion of the capacity is not the base of the company’s growth; it is only a part of the company’s intention. “I have a dentist’s surgery, not a grocery. What you choose – for example in the case of an implantation – that will become a part of your body for a lifetime. So, there is only one solution, and this one is the only good solution!” The core values of the organisation are providing a high standard of living and more free time for the owner, but in this case, the owner also aims at high self-achievement by being an expert in dentistry. The expertise and the premium quality is the base of the business model. The aim of this model is to ensure highly qualified services with the most modern technology. The quality orientation is noticeable in the firm’s environment and atmosphere. As mentioned earlier, this conscious positioning supposes certain management knowledge and incremental planning but misses any proactivity, such as seeking for new opportunities and market gaps, monitoring the consumer’s demand and the competitors’ activities. The main target is to secure the status quo and the organisation’s position in the market. “We haven’t got any objectives. We have already achieved our aims. We have a good life with more-and-more free time, but we believe that no one can be good enough for his job. Developing specialised knowledge is very important for me and it is a fundamental for the business, too”. The company doesn’t use any marketing tools constantly and consistently. There is a lack of consciousness in the marketing activity. No planning and no monitoring, hence the use of marketing tools is rather random. This is no surprise, since the owner’s aim is to secure the company’s market position, rather than to look for new market niches. “We have a website and we spend a certain amount of money on online marketing every month. I know it’s important that we also present the company online, but I’m not interested in looking for new clients”. Such marketing initiatives are fully inefficient, because the missing organisational objectives and motivating factors ends up in over spending. “The present situation and the future prospects are satisfactory for me”. This second case has more similarities with the family business than differences from it. This firm’s significant advantages are higher benefits and larger capacity, but both the family business and the expert have to deal with the same weaknesses and threats. The expert kind of organisation is isolated too, therefore it is also vulnerable. The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 159 4.3 Case 3: the marketer The absence of the awareness and intuitive decision-making is also a characteristic of the third segment. The firm’s primary target is to attain as many people as possible, but the only tool to reach new customers is the attractiveness of low-priced service. The focal point of growth is the enhancement of the quantity and capacity. The target customers are not only locals, but prospective clients from Western-Europe. Those, who can’t afford the service of their local dentists. During the interview, it was the first time that the word bargain appeared. So, the base of the marketer’s competitive advantage is the difference between the Hungarian and Western European prices. “The technological costs are here the same as everywhere in Europe, because we use Swedish and German materials and tools. The doctors’ and the surgeons’ costs are one third of the foreign prices”. The most important advantage of the marketer in contrast to the family business and the expert is the capability of attaining foreign markets successfully. In order to achieve it, the venture operates with a well-functioning marketing activity. “Our target countries are England, Germany and Austria”. The service portfolio is diversified; the core activity is complemented with related services such as a beauty salon and airport transfer. It is clear that the marketer can afford a higher standard of service than the family business or the expert, but these new elements are only imitations, not innovations. These phenomena exist due to the scarcity of the entrepreneurial approach and the advanced management skills. The owner-manager is aware of the role of marketing tools. Based on his insight, he designed a service package which elements are put together rather randomly. This is a threat: the company can reach a broad consumer base with the extended marketing activity; they can lure the clients to Hungary but can’t cope with the most serious risk factor of the low-cost clinics, which is the dropout. The dropout is a general phenomenon, there is a chance that the patient will change his or her mind once arriving at the dentistry and decides to buy service from another clinic. Consequently, price-based competition leads also to a vulnerable market position. Because of lacking innovative, self-developed ideas and initiatives which would prevent high drop-out rate, the venture needs to compensate with extensive marketing activities. The low margin together with the low conversion rate also means that marketing expenditures are high leaving less for the organisation to spend on innovative ideas. “We invest in innovations if it’s really necessary”. The way to cope with these challenges is to develop the management skills to make the decision-making conscious instead of intuitive, which could lead to a more effective operation. 4.4 Case 4: entrepreneurial marketer The following parameters are the main characteristics of the last analysed organisation: reactivity, constant flow of innovations, seeking for new opportunities, aggressive growth targets, and powerful branding. The core values of the firm are the premium service, the focus on innovation, the entrepreneurial approach on all levels of the organisation. As for the employees, their number is high, they are loyal, their working environment is luxurious, and everybody has the freedom to introduce their own ideas to develop or change something. “The waiting room is beautiful, as you could see it. But our office, lunch room and storage room are also beautiful!” The only rule is that the performance of the individual or that of the organisation must increase. If a technological novelty 160 R.Zs. Szabo et al. becomes affordable on the market, and it hasn’t got any medical risk, it will be integrated as soon as possible. These bottom-up initiatives are the main resources of the firm and they make the flexibility and the ability to react quickly and proactively possible. The firm uses every possible information sources and continuously and intentionally monitors industry trends and competition. “If I hear something, for example in the bus stop, I can present it at the weekly meeting. If the others reckon it interesting, I get the chance to work out the idea”. Dental tourism is a good example of the firm’s proactivity. The expression ‘dental tourism’ became the keyword of the company’s communication very early, in 2006. The media started to use it in 2007. Thanks to such a foresight, the company became very early a reference in the industry. The constant state-of-the-art technology serves the aims of the differentiation. “We bought a new diagnostic instrument. There are 2 or 3 of these in the country now. You can check it on our website!” The service portfolio is more developed too; the firm offers a well-organised service package, a so called ‘dental week’, which includes travel tickets, accommodation in the own hotel-clinic, free-time activities, dental and beauty treatments. This conscious product planning results in high commitment by the clients and eliminates the marketer’s main risk factor, the high dropout rate. The targets of this marketing are most Western European countries; furthermore, the company uses all existing online and offline channels to reach the target audience. So it can be concluded that marketing is a fundamental element of the business model. The company focuses only on new customers; there are not many repeat customers. “A new tooth is perfect for 20–25 years. Why should the client come back from England?” To summarise, the innovative approach along with the opportunity-seeking, advanced management skills and aggressive expansion targets result in a flexible, proactive, and fast-growing organisation. Thanks to these features, the company is able to influence the industry trends and can create new standards. The management and the marketing skills together lead to the firm’s current market-leader position. 5 Discussion of emergent cases 5.1 Theory development The case studies were carefully analysed in order to deepen our understanding of entrepreneurial behaviour of founder-managers in SMEs with regard to using guerilla marketing techniques. One aim of the research was to highlight the role of know-how, which was examined through the awareness of the operation and the ability to manage complex processes. The second aim of the research was to contribute to the development of the know-who concept, which was captured through attitude toward marketing and the marketing activity of the firm. As the findings of the qualitative research indicate, there is heterogeneity between the cases in their knowledge stocks. The results are summarised in a 2 × 2 matrix (Figure 2) in which authors identified four different types of the small ventures based on their know-how and know-who awareness. Each category varies from the others in at least the degree (low/high) of one factor (know-how/know-who). The elements of the matrix are the following: Family Business (low know-how and know-who), Expert (high know-how, low know-who), marketer (low know-how, high know-who) and the entrepreneurial The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 161 marketer (high know-how and know-who). The cases also suggest that the model is dynamic in nature. It is feasible to change behaviour and move from one category to another, however, the movements are rather restrictive in nature. Figure 2 Degree of know-how and know-who in SMEs HIGH Expert Entrepreneurial marketer Family business Marketer KNOW-HOW (Management skills) LOW LOW HIGH KNOW-WHO (Marketing skills) 5.2 Develop know-who skills The family business is vulnerable, relying on its current customers. It doesn’t make any effort to observe the market or its customers; therefore it is not able to react to changes. It has two ways to alter its position in the model. One way is moving up to the expert category through service development. However, it is not the proposed way because the firm will remain isolated unless it is ready to invest into know-who skills. The recommended way, is to move in the direction of the marketer through development of marketing and the organisational knowledge of the market, the customers and their needs. From the firm’s side it will demand most of the changes in the marketing approach, the attitude to marketing. At this point the movement in any directions demands the improvement of managerial and marketing knowledge of small and medium enterprises. Firms with low know-who skills can be described as the following: • there is lack of an entrepreneurial way of thinking and lack of novel, innovative marketing • they aren’t able to change and they mostly don’t realise the need to do so • they are dependent on their current customer base, hence they are vulnerable. 5.3 Develop know-how skills The marketer carries the germ of entrepreneurship, which is manifested mostly in its marketing activity. A marketer organisation lacks awareness of the expert, because it hasn’t got enough management knowledge and skills. It focuses on reaching the mass market and attaining as many customers as possible with no frills services. The marketer invests huge amounts of money in marketing, and as a result it doesn’t have much to spend on innovations. However, it has more growth opportunities than the family business or the expert. These opportunities fall behind the entrepreneurial marketer’s 162 R.Zs. Szabo et al. because the marketer has not enough knowledge to manage these processes. With managerial knowledge, the marketer could become an entrepreneurial marketer and could manage the risk better and improve the efficiency of its activities. Firms with low know-how skills can be described as the following: • they aren’t able to manage complex processes, and they lack awareness and bigger developments • they need to improve their management knowledge • they need to invest in knowledge and developments in order to reach the upper categories of the model (see arrows in Figures 3 and 4). Figure 3 Movement through changing the attitude to marketing HIGH Expert Entrepreneurial marketer Family business Marketer KNOW-HOW LOW LOW HIGH KNOW-WHO Figure 4 Movement through improving the management skills HIGH Expert Entrepreneurial marketer Family Business Marketer KNOW-HOW LOW LOW KNOW-WHO HIGH 5.4 The characteristics of the entrepreneurial marketer The entrepreneurial marketer is the real entrepreneur. The entrepreneurial marketer observes the market, customers, rivals, and collects information about its environment steadily. The entrepreneurial marketer is proactive, looks continuously for latent needs, and opportunities, focuses on innovation at an organisational level and aims on growth. The entrepreneurial marketer is willing to take a risk if it is manageable and employs creative, novel, proactive marketing techniques in an entrepreneurial approach and in an effective way. The entrepreneurial marketer is successful and has enough resources to maintain the firm’s position. The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 163 The entrepreneurial marketer is more conscious and manages processes better than the marketer, so firm activities are more successful and effective. In addition, the entrepreneurial marketer is more creative, can market better its professional knowledge and is able to manage more complex processes than the expert. The entrepreneurial marketer is able to adapt to changes and has growth opportunities, unlike the expert. An SME needs to have an entrepreneurial way of thinking in both, operation and marketing in order to be successful in the long run. There is a correlation between the degree of know-how and know-who, and the level of consciousness in the firm and the success of marketing activity are in a close connection with each other. Consequently, it is important to develop both the managerial skills and marketing knowledge. The know-how and know-who model draws attention to the importance of knowledge in being a successful entrepreneur and a marketer at the same time. An additional finding was the importance of the use of marketing tools in practice. The entrepreneurial Marketer’s creative initiative to reach the target market effectively is in line with the findings of Maritz (2010). Findings also underline that some of the online marketing tools, like search engine marketing, social network marketing, paying attention to the customers, improving the service standard by listening to feedback are key factors in the dental service industry. The tracking of the customers, following with attention and continuous contact with them has to be the base of a dental firm’s business model. The following marketing initiatives and tools of Maritz (2010) were identified in the case of the entrepreneurial marketer: • Improving sales by listening to feedback. • Generating sales using an online newsletter. The communication and promotion through e-mail is one of the most important channels of the entrepreneurial marketer. • Using big online search options. This is one of the two bases of the entrepreneurial marketer’s business models. The search engine marketing and the related tools are the most important marketing channels to reach the foreign markets. • Targeting online customers. The target audience is the segment of 30- to 40-year-old women with an average income from the UK, Ireland, France, and the Netherlands. They are most easily accessible with online tools. • Turning customers into raving fans. A widely used method to reach new customers is the free-of-charge annual check-up. Another way is offering free of charge travel and other services for those who brings a new patient to the clinic. • Refreshing your brand. The brand’s constant repositioning is indispensable, because the customer’s needs and trends change quickly in the dental, healthcare and beauty industries. The current keyword is the aesthetic instead of the dental treatment or implantology. • Implementing best practice from other industries. Dental tourism is a convergent industry; it integrates elements of healthcare, dental and travel industries. • Targeted advertising and integrated marketing communications. Compared to ‘conventional’ tools of marketing, entrepreneurial marketing activities seem to be more effective especially for targeting tailored services. 164 R.Zs. Szabo et al. • On the value of local knowledge. The entrepreneurial marketers have their own dentists in every target country. Their tasks are making highly reliable pre-diagnoses for the prospective clients as well as to provide follow-up services to customers. • Network, network, and network. For both information gathering about market demand as well as to distribute information to the market. In addition, the case studies highlighted that not only the modern tools can be successful. The excessive use of modern marketing tools can do harm to the overall efficiency of the organisation’s marketing activity. The aim is to maximise the portfolio’s effectiveness, not the individual use of the tools. The entrepreneurial marketer uses a balanced marketing toolbar, which contains both modern and conventional methods, such as greeting cards, PR-articles and advertisements in healthcare magazines. 6 Conclusions and Implications In this paper the authors introduced a widely applicable model for both researchers and business professionals: • the case studies highlight the different effects of know-how and know-who on the use of entrepreneurial marketing tools and techniques • the four identified SME categories in the model provide an explanation of the connection between marketing activity and level of management knowledge factors • the model draws attention to the role of knowledge factors for market development. An important conclusion of the research is that the fully intuitive decision-making and the technological knowledge in itself are not sufficient for achieving long-term success. The keyword is awareness, because the opportunities of the organisation may remain hidden because of wrong goal-setting, which arises from the scarcity of advanced management skills and an obsolete marketing approach. To summarise, the manager of an SME is strongly recommended to invest in knowledge, in the development of managerial and marketing knowledge and skills. For policymakers, the research underlines the increasing role of SME education. Since SMEs play an important economic role by contributing to employment, GDP, and exports, as well as being a great source of innovation. It cannot be overemphasised that conscious management practices need to be developed in founders and managers, in order to balance professional knowledge with the effective use of entrepreneurial behaviour. The model, however, needs to be tested on a large sample with advanced statistical methodologies. It can be also envisioned that different industries may have different knowledge-demand; hence a comparison of industries may add key insights to the model. Acknowledgements The authors hereby would like to express their gratitude to the Hungarian National Scientific Research Fund as well as to Budapest Economic Research and Development Foundation for supporting the research project. The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 165 References Barker, V.L., III and Mueller, G.C. (2002) ‘CEO characteristics and firm R&D spending’, Management Science, Vol. 48, No. 6, pp.782–801. Byers, T., Kist, H. and Sutton, R.I. (1997) ‘Characteristics of the entrepreneur: social creatures, not solo heroes’, in Dorf, R.C. (Ed.): The Handbook of Technology Management, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. Campbell, A. (1985) ‘Guerilla marketing – a survival of the fittest in a jungle of promotions’, Canadian Business, Vol. 53, No. 3, p.150. Carson, D. and Cromie, S. (1989) ‘Marketing planning in small enterprises: a model and some empirical evidence’, Journal of Marketing Management, Part 1, Vol. 5, No.16, pp.33–49. Cummins, D., Gilmore, A., Carson, D. and O’Donnell, A. (2000) ‘What is innovative marketing in SMEs? Towards a conceptual and descriptive framework’, AMA Conference Proceedings, July. Eggers, F. (2010) ‘Grow with the flow – entrepreneurial marketing and thriving young firms’, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp.227–244. Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989) ‘Building theories from case study research’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp.532–550. Gaedeke, R.M. and Tootelian, D.H. (1980) Small Business Management, Goodyear Publishing Co., California. Gartner, W.B. (1994) ‘Marketing/entrepreneurship interface: a conceptualization’, in Gerald E. Hills (Ed.): Marketing and Entrepreneurship: Research Ideas and Opportunities, pp.25–34, Quorum Books. Gruber, M. (2004) ‘Marketing in new ventures: theory and empirical evidence’, Schmalenbach Business Review, April, Vol. 56, pp.164–199. Guth, W.D. and Ginsberg, A. (1990) ‘Guest editor’s introduction: corporate entrepreneurship’, Strategic Management Journal, Summer Special Issue, Vol. 11, pp.5–16. Hambrick, D.C. and Mason, P.A. (1984) ‘Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp.193–206. Hansen, D.J. and Eggers, F. (2010) ‘The marketing/entrepreneurship interface: a report on the ‘Charleston summit’, Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp.42–53. Harryson, S.J. (2006) Know-who Based Entrepreneurship: From Knowledge Creation to Business Implementation, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK. Hill, D. (2009) ‘Ten steps to sell more product now’, Biocycle, August. Hill, J. (2001) ‘A multidimensional study of the key determinants of effective SME marketing activity: Part 1’, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, Vol. 7, No. 5, pp.171–204. Hills, G.E. and Hultman, C.M. (2006) ‘Entrepreneurial marketing’, in Lagrosen, S. and Vensson, G. (Eds.): Marketing – Broadening the Horizons, pp.219–234, Student literature. Hills, G.E., Hultman, C.M. and Miles, M.P. (2008) ‘The evolution and development of entrepreneurial marketing’, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 46, No. 13, pp.99–112. Hoang, H.A. and Antoncic, B. (2003) ‘Network-based research in entrepreneurship: a critical review’, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 18, pp.165–187. Hortovanyi, L. (2009) ‘Entrepreneurial management in Hungarian SMEs’, Unpublished PhD dissertation, Corvinus University of Budapest, Faculty of Business Administration. Johnson, B. and Lundvall, B.A. (2001) ‘Why all this fuss about codified and tacit knowledge’, DRUID Winter Conference, 18–20 January. Katila, R. and Shane, S. (2005) ‘When does lack of resources make new firms innovative?’, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 48, No. 5, pp.814–829. 166 R.Zs. Szabo et al. Kaya, M., Steffens, P. Hearn, G. and Graham, P. (2010) ‘How can entrepreneurial musicians use electronic social networks to diffuse their music’, 7th AGSE International Entrepreneurship Research Exchange, 2–5 February 2010. Kraus, S., Fink, M., Rößl, D. and Jensen, S.H. (2007) ‘Marketing in small and medium sized enterprises’, Review of Business Research, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp.1–11. Kraus, S., Harms, R. and M. Fink (2010) ‘Entrepreneurial marketing: Moving beyond marketing in new ventures’, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp.19–34. Levinson, J.C. (1984) Guerilla Marketing. Secrets for Making Big Profits from Your Small Business, Houghton Mifflin Co., New York, NY. Maritz, A. (2010) ‘A discursive approach to entrepreneurial marketing: integrating academic and practice theory’, 7th AGSE International Entrepreneurship Research Exchange, 2–5 February 2010. Martin, D.M. (2009) ‘The entrepreneurial marketing mix: qualitative market research’, An International Journal, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp.391–403. Miles M.P. and Darroch, J. (2006) ‘Large firms, entrepreneurial marketing processes, and the cycle of competitive advantage’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 40, Nos. 5/6, pp.485–501. Miller, D. and Friesen, P.H. (1982) ‘Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: two models of strategic momentum’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 3, No. 24, pp.1–25. Moore, C.W., Broom, H.N. and Longenecker, J. (1983) Small Business Management, South Western Publishing Co., Cincinnati, Ohio. Morris, M. and Lewis, P.S. (1995) ‘The determinants of entrepreneurial activity implications for marketing’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 29, No. 7, pp.31–48. Morris, M.H., Schindehutte, M. and LaForge, R.W. (2002) ‘Entrepreneurial marketing: a construct for integrating emerging entreprenenurship and marketing perspectives’, Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, Fall, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp.1–20. Mueller, P. (2005) Exploring the Knowledge Filter: How Entrepreneurship and University-industry Relations Drive Economic Growth, available at http://doku.iab.de/fdz/events/2005/Mueller.pdf (accessed 24 June 2010). O’Dwyer, M., Gilmore, A. and Carson, D. (2009) ‘Innovative marketing in SMEs – does it exist?’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 43, Nos. 1/2, pp.46–61. Pendergast, W.R. (2004) ‘Entrepreneurial contexts and traits of entrepreneurs’, Working paper, Orfalea College of Business, California State Polytechnic University San Luis Obispo, California. Peterson, R. and Berger, D. (1971) ‘Entrepreneurshipin organizations’, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 10, pp.97–106. Rößl, D., Kraus, S., Fink, M. and Harms, R. (2009) ‘Entrepreneurial marketing: geringer mitteleinsatz mit hoher wirkung’, Marketing Review St. Gallen (Thexis - Fachzeitschrift für Marketing), Vol. 26, No. 1, pp.18–22. Schmengler, K. and Kraus, S. (2010) ‘Entrepreneurial marketing over the internet: an explorative qualitative empirical analysis’, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp.56–71. Schulte, R. and Eggers, F. (2010) ‘Entrepreneurial marketing and the role of information – evidence from young service ventures’, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp.56–74. Shane, S. (2001) ‘Where is entrepreneurship research heading? Keynote’, National University of Singapore Conference on Technological Entrepreneurship in the Emerging Regions of the New Millennium, 28–30 June. Simpson, M. and Taylor, N. (2000) ‘The role and relevance of marketing in SMEs: a new model, small firms: adding the spark’, 23rd ISBA National Small Firms Policy and Research Conference, pp.1093–110. The role of knowledge in entrepreneurial marketing 167 Stevenson, H.H. and Gumpert, D.E. (1985) ‘The heart of entrepreneurship’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 63, No. 2, pp.85–94. Strokes, D. (2000) ‘Putting entrepreneurship into marketing: the process of entrepreneurial marketing’, Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp.1–16. Szabó, R.Zs. (2010) ‘Hálózatok vezetői nézőpontból’, in Balaton, K., Hortovanyi, L., Incze, E., Laczkó, M., Szabó, R.Zs. and Tari, E. (Eds.): Stratégiai Menedzsment, AULA, Budapest. Timmons, J. (1994) New Venture Creation, 4th ed., Irwin, Burr Ridge, IL. Tsui, A.N. and Farh, L.J. (1997) ‘Where guanxi matters: relational demography and guanxi and the social context’, Work and Occupation, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp.36–79. Wickham, P.A. (2006) Strategic Entrepreneurship, 4th ed., Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, England. Yin, R.K. (1994) Case Study Research, 2nd ed., Sage Publications, London.