* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Here - Ohlone - University of California, Santa Cruz

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Junction Grammar wikipedia , lookup

Transformational grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Morphology (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Agglutination wikipedia , lookup

Relative clause wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Preposition and postposition wikipedia , lookup

Dependency grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Musical syntax wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Antisymmetry wikipedia , lookup

Integrational theory of language wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Contraction (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Sloppy identity wikipedia , lookup

Romanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Distributed morphology wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

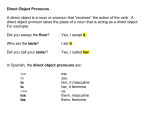

Bound variable pronoun wikipedia , lookup